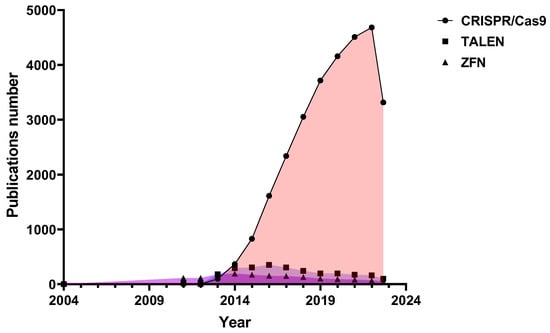

Scientific interest in programmable nucleases has only been growing in the last decade, and most often there are scientific papers devoted to the development and study of CRISPR/Cas9 nucleases (Figure 1). Last year marked 10 years since the development of CRISPR/Cas9 as a genome editing tool, and Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier were awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for discovering one of gene technology’s sharpest tools: the CRISPR/Cas9 genetic scissors.

From the very beginning, the CRISPR/Cas9-based therapeutic approach was the most promising. 10 years seems like a short time in the innovative drug discovery process, but CRISPR-based therapies have made significant progress. For the first five years, researchers have been modifying existing CRISPR/Cas9 proteins to achieve increased genome editing efficiency and reduced off-target activity and developing CRISPR for clinical use for the first time. Over the next five years, new CRISPR/Cas proteins with different capabilities were discovered and developed, the CRISPR toolbox expanded, and the first CRISPR/Cas9 trials were conducted, sometimes with amazing results.

2. CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery Methods

The success of genome editing depends on the specificity and efficiency of the Cas9 protein, the design of the guide RNA, and the efficiency of the delivery of elements of the CRISPR/Cas system into the target cell. CRISPR/Cas9 elements can be delivered using different methods, i.e., physical methods, viral and non-viral vector delivery, etc. Physical methods of delivery imply short-term disruption of the target cell membrane and include electroporation, sonoporation, nano-injection, micro-injection, and hydrodynamic injection [

178]. Viral vectors are the earliest molecular tools for gene transfer to human cells; they transfer nucleic acids encoding CRISPR/Cas9 components to target cells in the envelope of a virus, for example, an adenovirus, adeno-associated virus, retrovirus, lentivirus, Epstein–Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, and bacteriophages [

179,

180]. In addition, alternative (non-viral) methods of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery, for example, by using lipid nanoparticles, polymer and hydrogel nanoparticles, hybrid gold, graphene oxide, metal-organic frameworks, black phosphorus nanomaterials, etc., were reported [

181].

Cas9 and guide RNA can be delivered to a cell via three different modes: (i) as a set of plasmid DNAs; (ii) as a combination of Cas9 mRNA and guide RNA; and (iii) as pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) (Table 1).

Table 1. CRISPR/Cas9 delivery strategies.

To date, many strategies are available for CRISPR/Cas9 RNP delivery based on physical approaches and synthetic carriers. CRISPR/Cas9 RNPs were successfully delivered to target cells using microinjection [

182], biolistics [

183,

184], electroporation [

185,

186,

187,

188,

189], microfluidics [

190,

191], filtroporation [

192], nanotube [

193], osmocytosis [

194], synthetic lipid nanoparticles [

195], cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) [

196], lipopeptides [

197], dendrimers [

198], chitosan nanoparticles [

199], nanogels [

200], gold nanoparticles [

201], metal-organic frameworks [

202], graphene oxide [

203], black phosphorus nanosheets [

204], calcium phosphate nanoparticles [

205], and many more [

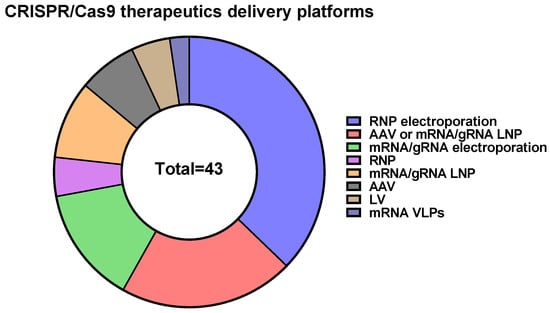

206]. It should be mentioned that CRISPR/Cas9-based therapeutics predominantly use electroporation of RNPs into target cells as a delivery method (

Figure 3).

Delivery of CRISPR/Cas in the form of RNPs is believed to have several advantages, including high editing efficiency, low nonspecific activity, editing beginning immediately after delivery to the cell, the ability to quickly screen the effectiveness of guide RNAs in vitro, and decreased immunogenicity due to the transient presence of CRISPR/Cas elements in the target cell. Thus, RNPs offer promising opportunities for CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing. However, RNP delivery is rather difficult due to the high molecular weight of Cas9 protein (~160 kDa) and the additional requirement for optimization of RNP loading with sgRNA. Moreover, several limitations are associated with RNP delivery due to the charge properties of the complex. There are a lot of methods for RNP delivery, but some of them seem to be expensive and cannot be scaled up; others carry an intellectual property burden. More investigations and optimizations are required to overcome the existing problems of Cas9 RNP delivery.

3. CRISPR/Cas9-Based Diagnostics

Since 2017, CRISPR/Cas proteins with collateral cleavage activity–Cas12 and Cas13, have been used in the field of molecular diagnostics [

207,

208,

209,

210]. The main feature of such diagnostics is that CRISPR/Cas complexes “recognize” target sequences with excellent specificity and subsequently cleave labeled reporter molecules. The Cas9 protein, the best-known representative of the Cas protein family, is also used for diagnostics, but the mode of action is different: the labeled CRISPR/Cas complexes “recognize” target sequences.

In 2016, CRISPR/Cas9 was for the first time mentioned as a part of a paper-based sensor to detect clinically relevant concentrations of Zika virus and to discriminate between closely related viral strains with single-base resolution. The assay was called NASBACC (from NASBA, Nucleic Acid Sequence-Based Amplification, and CRISPR Cleavage), had a colorimetric readout, and an LOD (limit of detection) = 6 × 10

5 copies/ml [

211]. Also, Vilhelm Müller et al. described an analysis based on optical DNA mapping of individual plasmids carrying antibiotic resistance genes of bacterial isolates in nanofluidic channels, which provides detailed information about these plasmids, including the presence/absence of antibiotic resistance genes. The described assay allowed the identification of antibiotic resistance genes using CRISPR/Cas9 and antibiotic resistance gene-specific guide RNAs (blaCTX-M group 1, blaCTX-M group 9, blaNDM, and blaKPC). During the analysis, the CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex linearizes circular plasmids in the region of the antibiotic resistance gene, and the resulting linear DNA molecules are identified using optical DNA mapping [

212].

Later, CRISDA [

213], CAS-EXPAR [

214], CRISPR-Chip [

215], and FLASH-NGS [

216] technologies were developed. CRISDA combines the strand-displacement amplification technique with the Cas9-mediated target enrichment approach and exhibits sub-attomolar sensitivity with an LOD = 1.5 × 10

2 copies/ml [

213]. The CAS-EXPAR technique has comparable sensitivity (LOD = 4.9 × 10

2 copies/ml) and does not require exogenous primers (primers are first generated by Cas9/sgRNA-directed site-specific cleavage of the target and accumulated during the reaction) [

214]. CRISPR-Chip represents ribonucleoprotein complexes formed by catalytically inactive Cas9 and target-specific sgRNAs immobilized on the surface of the graphene layer. When RNPs bind target DNAs, it causes a change in electrical current, which makes for a simple signal readout. CRISPR-Chip allows detection of femtomolar amounts of DNA without the need for target preamplification [

215]. In 2019, FLASH-NGS was introduced as a unique technology for sub-attomolar detection of low-abundance pathogen sequences. In FLASH-NGS, Cas9 is used to enrich (up to 5 orders of magnitude) the sample with a programmed set of sequences [

216].

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic gave rise to CRISPR/Cas9-based methods named FELUDA [

217], CASLFA [

218], VIGILANT [

219], “Biotin-dCas9-LFA” [

220], LEOPARD [

221], and Bio-SCAN [

222].

FELUDA (FnCas9 Editor-Linked Uniform Detection Assay) is a semi-quantitative assay utilizing direct catalytically inactive FnCas9-based detection of PCR-amplified sequences. Target sequence in FELUDA is labeled with biotin and RNP–with FAM/FITC, which allows detection of results with lateral flow readout. FELUDA can detect nucleic acids with high sensitivity/specificity, and its LOD is 10 copies per reaction [

217].

CASLFA (Cas9-mediated lateral flow nucleic acid assay) can be performed in two different ways. The first option includes biotinylated amplicons, target-specific Cas9/sgRNA complexes, and AuNP-DNA probes, which are hybridized with the single-strand region of the amplicon released by Cas9/sgRNA-mediated unwinding. The second option includes sgRNA with a universal sequence in the stem-loop region for AuNP-DNA probe hybridization, biotinylated amplicon, and a target-specific Cas9/sgRNA complex. CASLFA can detect 200 copies per reaction [

218].

VIGILANT (VirD2-dCas9-guided and LFA-coupled nucleic acid test) is a nucleic acid detection technology based on the use of a fusion of catalytically inactive SpyCas9 and VirD2 relaxase. Target sequence is amplified using biotinylated oligos and is specifically bound by dCas9, while VirD2 covalently binds to a FAM-tagged oligonucleotide. Afterwards, the biotin label and FAM tag are detected by any available LFA with a limit of detection of 2.5 copies/μL [

219].

The Biotin-dCas9-LFA assay includes FAM-labelled amplicon, biotinylated target-specific dCas9/sgRNA complex (bdCas9), and a competing PAM-rich soak double-stranded oligonucleotide to prevent non-specific bdCas9/mismatched sgRNA binding. It should be noted that the biotin-dCas9-LFA limit of detection (LOD) is similar to that of qRT-PCR [

220].

Chunlei Jiao et al. found that RNA guides from Cas9-RNA complexes from

Campylobacter jejuni can also originate from cellular RNAs unassociated with viral defense. This fact led to the reprogramming of tracrRNAs so that they could link the presence of any RNA of interest to DNA targeting with different Cas9 orthologs (CjeCas9, SpyCas9, and Sth1Cas9). This work gave rise to a multiplexable, ultrasensitive diagnostic platform named LEOPARD (leveraging engineered tracrRNAs and on-target DNAs for parallel RNA detection) [

221].

Bio-SCAN (biotin-coupled specific CRISPR-based assay for nucleic acid detection) is a simple, rapid, specific, and sensitive pathogen detection platform that does not require sophisticated equipment or technical expertise. Within 1 h of sample collection, Bio-SCAN can detect a clinically relevant level (4 copies/μL) of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. Bio-SCAN consists of FAM-tagged oligonucleotides, biotinylated catalytically inactive SpyCas9, and AuNP-anti-FAM antibodies. The target nucleic acid sequence is amplified in 15 min via RPA and then detected on commercially available lateral flow strips [

222].

CRISPR/Cas9 offers an opportunity for the development of a wide variety of point-of-care diagnostics (more than 10 diagnostic platforms have been published to date), but it still remains an investigational rather than practical approach. CRISPR/Cas9-based pathogen detection platforms are rather simple, possess excellent specificity, are very sensitive (and even ultrasensitive), and are able to detect clinically relevant levels of pathogen-specific nucleic acids. Some CRISPR/Cas9-based nucleic acid detection platforms may become the basis for express point-of-care laboratory and home tests.

4. CRISPR/Cas9-Based Therapeutics

Nowadays, CRISPR/Cas is used to study and develop therapeutic approaches for the treatment of a wide variety of human diseases [

2,

223,

224,

225,

226,

227].

Genome editing using CRISPR/Cas systems is used to develop antiviral therapy to treat infectious diseases. The therapeutic effect is to be achieved either by altering host genes important for the viral life cycle or by targeting viral genes required for replication [

228]. Today, several approaches to HIV therapy development are based on genome editing technology.

CRISPR/Cas9 has been used to induce site-specific genome modification in human cells in vitro and in vivo using mouse models of HIV infection [

229,

230,

231,

232,

233]. Numerous academic laboratories have successfully performed CD4+ T cell CCR5 receptor knockouts using CRISPR/Cas9. This approach was shown to inhibit HIV-1 infection without significant side effects [

232]. CCR5 editing in both the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) population and the CD4+ T lymphocyte population is a promising strategy for creating HIV-resistant cells. However, this approach is ineffective against CXCR4 (C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4)-tropic HIV strains. It has been shown that CRISPR/Cas9 can be used to edit the gene encoding CXCR4 with high precision and efficiency. Knockout of the HIV co-receptor CXCR4 is accompanied by minor off-target effects and provides resistance to HIV infection caused by CXCR4-tropic HIV strains [

230,

234,

235,

236]. This approach could be used to generate experimental and therapeutic primary human CD4+ T cells, providing an alternative treatment for HIV-1 X4 infection. At the same time, simultaneous knockout of both HIV co-receptors Chemokine C-C-Motif Receptor 5 (CCR5) and CXCR4 leads to a decrease in the expression of CCR5 and CXCR4, which makes the modified cells resistant to infection with R5 and X4 tropic viruses, even when using double tropic viruses [

230].

In recent years, CRISPR technology has been successfully used to reduce or eliminate persistent viral infections in vitro and in animal models in vivo, raising the prospect of its application in the treatment of latent and chronic viral infections [

237].

CRISPR/Cas technologies have been used to combat HIV infection in vitro in various cell lines. At the same time, it was possible to achieve not only suppression of HIV gene expression in infected T cells and microglial cells but also to remove HIV proviral DNA from many other cell lines, including neuronal progenitor cells, which represent latent reservoirs of HIV infection [

238,

239,

240]. CRISPR/Cas systems have also been shown to be effective in combating HIV infection in vivo. Thus, HIV proviral DNA was eliminated from the spleen, lungs, heart, colon, and brain of animals in a humanized model of chronic HIV infection [

240]. In addition, using CRISPR/Cas technology, HIV proviral DNA was removed from infected human peripheral blood mononuclear cells using a transgenic mouse model [

241].

In 2017, the CRISPR/Cas9 system was used to remove a full-length fragment of hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA that was chromosomally integrated and episomally localized as cccDNA in chronically infected cells. This approach allowed complete eradication of HBV in a stable infected cell line in vitro. This suggests that the CRISPR/Cas9 system is a potentially powerful tool for eradicating chronic HBV infection and curing HBV completely [

242,

243].

In addition, the CRISPR/Cas system has been successfully used to combat herpesvirus infections in vitro. It was shown that the simultaneous use of several guide RNAs made it possible to significantly reduce the replication of herpes simplex virus 1 in cells [

244,

245]. Using CRISPR/Cas, it was also possible to eliminate up to 95% of the DNA of the Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus within 11 days, after which mutant forms of the virus appeared, resistant to the action of CRISPR/Cas [

244]. CRISPR/Cas systems have also been shown to eliminate other viral pathogens in vitro, such as the John Cunningham virus and the human papillomavirus HPV-16 and HPV-18 [

246,

247].

CRISPR/Cas9 was used to develop therapeutic approaches for the treatment of monogenic diseases such as cystic fibrosis [

248,

249,

250,

251], sickle cell disease [

30,

252,

253,

254], thalassemia [

255,

256,

257,

258], Huntington’s disease [

259,

260,

261,

262,

263], Duchenne muscular dystrophy [

264,

265,

266,

267,

268,

269,

270], hemophilia [

271,

272,

273,

274,

275], diabetes [

276,

277,

278,

279,

280] and cardiovascular diseases [

281,

282,

283,

284,

285].

What is more, novel therapeutic approaches for cancer treatment are based on CRISPR/Cas9. CRISPR/Cas9 was used for the development of CAR-T cells (T cells with a chimeric antigen receptor) that have high antitumor activity, including “universal” CAR-T allogeneic T cells on which endogenous T-cell receptor (TCR) and Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) are eliminated [

286,

287,

288,

289,

290,

291,

292,

293,

294,

295,

296,

297,

298]. Also, CRISPR/Cas9 was used to produce CAR-T cells in which a CAR or TCR cassette was introduced into the endogenous TCR gene locus to mitigate graft-versus-host disease, preventing random integration of the cassettes and ensuring uniform CAR (chimeric antigen receptor) expression [

299,

300,

301,

302].

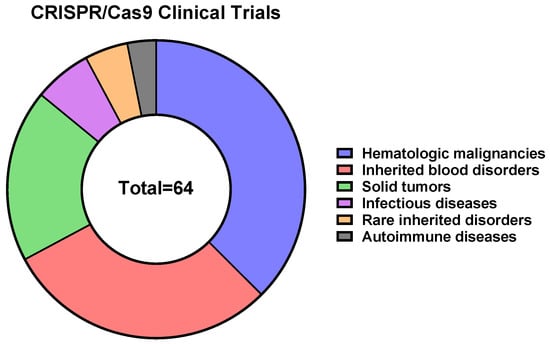

To date, 64 CRISPR/Cas9-, 4 CRISPR/Cas9 base editors-, and 2 Cas-CLOVER-based therapeutics are in clinical trials, according to the CRISPR Medicine News website (

https://crisprmedicinenews.com/clinical-trials/, accessed on 5 September 2023). The vast majority of CRISPR/Cas9-based therapeutics are directed against hematologic malignancies (~38%), inherited blood disorders (~29%), and solid tumors (~19%) (

Figure 4).

Recently, encouraging news has emerged: some patients are functionally cured of sickle cell disease or beta thalassemia, and the edited cells reside in the bone marrow, indicating the potential for long-term treatment. Cancer immunotherapy trials are in the early stages, but the safety and tolerability of the treatments look promising moving forward with newer versions of the editing technology, off-the-shelf products, moving toward new cancer targets, and even developing new cell types for immunotherapy.

All treatment methods mentioned above are relatively new. Positive results still require long-term follow-up to see whether the treatment remains effective, whether patients suffer unwanted changes, and whether patients have immune responses against Cas proteins.