Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Bat lyssaviruses have become the topic of intensive molecular and epidemiological investigations. Since ancient times, rhabdoviruses have caused fatal encephalitis in humans which has led to research into effective strategies for their eradication.

- lyssavirus phylogroups

- Chiroptera

- evolution

1. Introduction

The Order Chiroptera has a Laurasiatherian origin (“laurasian beasts”), evolved between 50 and 70 million years ago (MYA), and has undergone rapid diversification [1][2]. Due to their capabilities of self-powered flight and echolocation, bats [3] comprise over 20%, or more than 1460 species, of all modern mammals and are globally distributed, with the exception of the extreme polar regions [4]. They have many characteristics that differentiate them from other mammalian species, such as their unique physiology [5][6], metabolism [7], and immune system [2][8][9]. These features make them a suitable reservoir for viral zoonoses [4][10][11] and more than 200 viruses have been isolated from or detected in bats [12][13][14]. The order comprises 45 species in Europe [15] from two superfamilies, the Rhinolophoidea and Vespertilionoidea [16], representing a natural reservoir of RNA-viruses.

Viruses from 11 families have been isolated on the continent [17] and bat lyssaviruses in Europe (family Rhabdoviridae) have been the subject of detailed reviews [18][19][20][21]. Lyssaviruses are a genus of negative-sense single-strand RNA viruses in the family Rhabdoviridae, subfamily Alpharhabdovirinae. Notably, they are members of the order Mononegavirales, which includes other prominent zoonotic pathogens such as filoviruses (Ebola, Marburg, etc.) and the neurotropic Bornaviridae [22]. Based on genetic divergence, lyssaviruses are classified into 21 different viral species. Recently, several putative new lyssaviruses were published [23][24][25][26]. Apart from the Mokola virus (MOKV) and Ikoma lyssavirus (IKOV), which have rodents and African civets as a reservoir, respectively [25][27][28], the rest of the lyssaviruses can be transmitted by Chiroptera [27][29]. According to the most recent ICTV report [24], lyssavirus names are provided here followed by the traditional abbreviations used to identify their isolates: rabies virus (RABV), Aravan virus (ARAV), Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), Bokeloh bat lyssavirus (BBLV), Duvenhage virus (DUVV), European bat lyssavirus 1 (EBLV-1), European bat lyssavirus 2 (EBLV-2), Gannoruwa bat lyssavirus (GBLV), Ikoma lyssavirus (IKOV), Irkut virus (IRKV), Khujand virus (KHUV), Lagos bat virus (LBV), Lleida bat lyssavirus (LLEBV), Mokola virus (MOKV), Shimoni bat virus (SHIBV), Kotalahti bat lyssavirus (KBLV), Divača bat lyssavirus (DBLV), West Caucasian bat virus (WCBV), Matlo bat lyssavirus (MBLV), and Lyssavirus Formosa, which includes Taiwan bat lyssavirus 1 (TWBLV-1) and Taiwan bat lyssavirus 2 (TWBLV-2) [21][24][30][31][32][33][34][35]. In fact, KBLV and MBLV are only tentative lyssaviruses.

2. Origin, Evolution, and Geographic Distribution of Bat Lyssaviruses

Despite the greater diversity of African lyssaviruses [36], Hayman et al. [37] assumed that they have a Palearctic origin and challenged “Out of Africa” hypothesis. The Lyssaviruses’ most recent common ancestor (MRCA) evolved from an insect rhabdovirus between 7000 and 11,000 years ago [30][38][39] which was transmitted to representatives of the order Chiroptera and spread globally [38][40]. According to Rupprecht et al. [30], Africa is the most likely home to the ancestors of taxa within the Genus Lyssavirus, family Rhabdoviridae. A large number of different lyssaviruses co-evolved with bats as ultimate reservoirs over millions of years. On the other hand, Velasco-Villa et al. [41] argue that in the Western Hemisphere before the arrival of the first European colonizers, rabies virus was present only in bats and so-called mesocarnivores (canids, raccoons, skunks, etc.). It is assumed that all mammals are susceptible to infection with the rabies virus. However, it is most possible that lyssaviruses will never be eradicated due to their presence in chiropteran hosts.

Lyssaviruses have undergone purifying selection followed by a neutral evolution of the viral genomes [42]. The low rate of nonsynonymous evolution of lyssaviruses is probably the result of constraints imposed by the need to replicate in multiple cell types (muscle, peripheral and central nervous systems, and salivary glands) within the host, which in turn boosts cross-species transmission (e.g., different groups of mammals), or because viral proteins are not subject to immune selection, which means existing lyssaviruses are well adapted to their reservoir [43][44].

The host switching of the classic rabies lyssavirus (RABV) from bats to other mammals is estimated to have occurred 800 to 1400 years ago, which does not explain the timing of the oldest putative human rabies cases, estimated to have circulated 4000 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia [45][46]. A possible explanation is that the Mesopotamian RABV lineage disappeared as a consequence of genetic drift (loss of polymorphism) or its high fatality rates [45]. According to Rupprecht et al. [47] and Badrane et al. [48], bats are the primary evolutionary host of rabies viruses as a reservoir of all existing lyssaviruses except MOKV and IKOV, whereas other mammals and humans only maintain several lineages of RABV, including the extinct Mesopotamian strain [30][45][49].

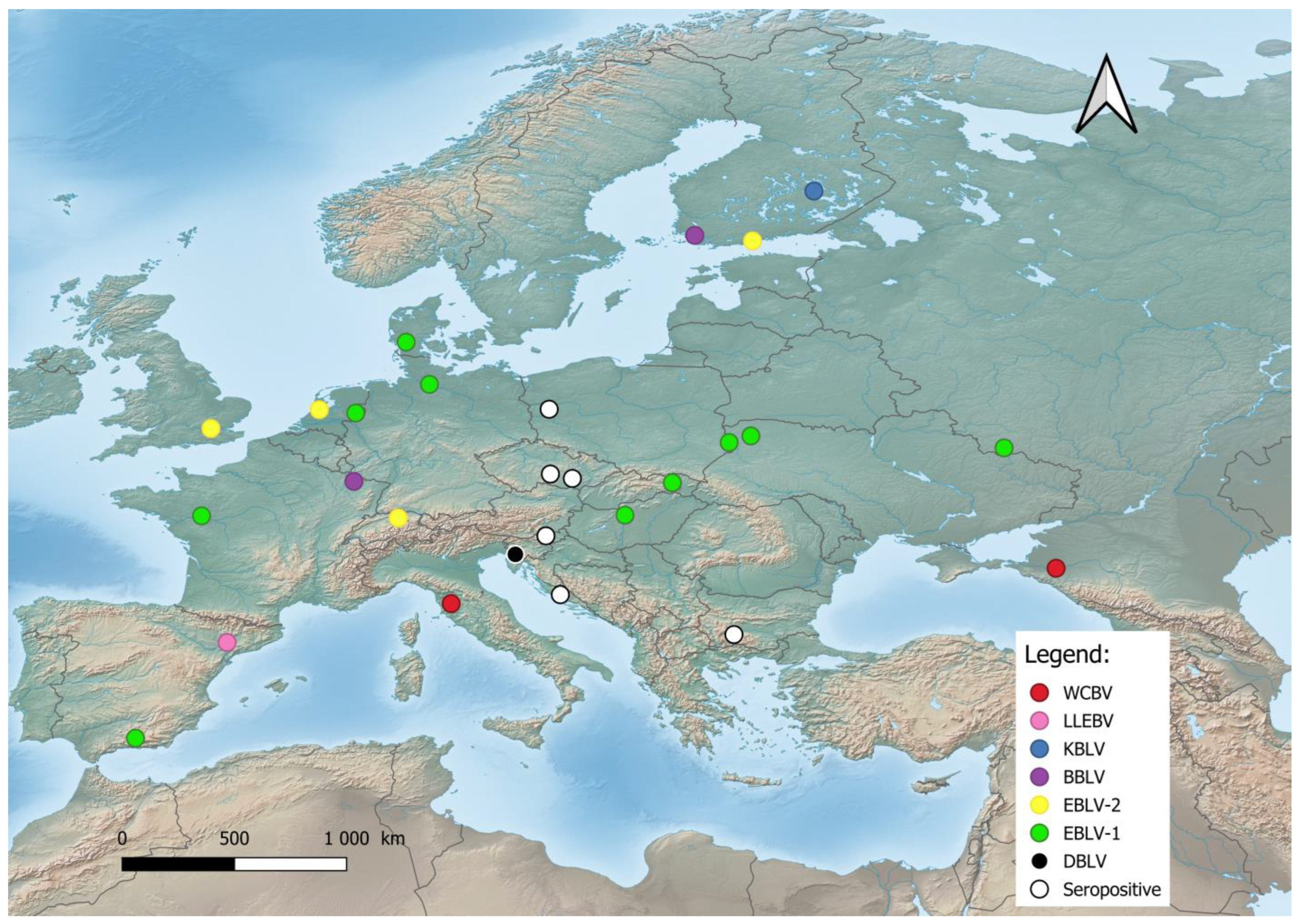

In Europe, bat lyssaviruses (Figure 1) were detected in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Finland, Denmark, Poland, Czech Republic, Germany, Switzerland, France, Spain, Hungary, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Ukraine, and Russia [19][21][35][50][51][52][53]. During the last two decades, previously unknown lyssaviruses were isolated as follows: WCBV in 2002 on the European side of the Caucasus Mts. [54], BBLV in 2010 from Germany [55], LLEBV in 2011 from Spain [56], KBLV in 2017 from Finland [23], and DBLV in 2014 from Slovenia [35].

Figure 1. Distribution of bat lyssaviruses in Europe. Abbreviations used: WCBV—West Caucasian bat lyssavirus; LLEBV—Lleida bat lyssavirus; KBLV—Kotalahti bat lyssavirus; BBLV—Bokeloh bat lyssavirus; EBLV-1—European bat lyssavirus 1; EBLV-2—European bat lyssavirus 2; DBLV—Divača bat lyssavirus, Seropositive—Seropositive Blood samples.

The most frequent lineages are EBLV-1, first reported in 1955 from Germany, and EBLV-2, isolated in 1985 in Switzerland [49][50]. EBLV-1 is exclusively detected in Serotine bats (Eptesicus serotinus), while EBLV-2 is mainly found in Daubenton’s bats (Myotis daubentonii). EBLV-1 is present in two forms: EBLV-1a and EBLV-1b. EBLV-1a displays a wide geographical distribution between France and Russia with phylogenetic homogeneity—an indication of extensive dispersal by bats [20][57]. Resent research has shown that EBLV-1 is associated with the bat E. serotinus of the mountainous parts of Southern Europe, such as the French Alps or the Iberian Peninsula [58]. EBLV-1 demonstrates the risk of spillover because of its host’s close phylogenetic relation with a different bat, the E. isabellinus. The phylogenetic analysis of nine EBLV-1 strains of E. serotinus distributed in the south of the Pyrenees revealed that two of them are closely related to EBLV-1a sequences from Southern France, i.e., this group expanded to Northern Spain. The results of the conducted research give the authors reason to assume the expansion of the EBLV-1a subtype across southern France, with a very recent arrival to the Iberian Peninsula, i.e., a current southwards dissemination [50]. In contrast, EBLV-1b is distributed between Spain and Poland with a well-defined geographic structure, indicating restricted contact between bat populations [20][50]. Therefore EBLV-1b had the potential to spread southwards according to the E. isabellinus distribution. The lineage of EBLV-1 is presumed to have arisen 500 to 750 years ago and has a relatively recent origin [57]. Conversely, the lineage of EBLV-2 is dated to more than 8000 years ago, with current establishment in Europe within the last 2000 years. [59]. EBLV-2 has been reported in Western Europe and is also represented by two forms: EBLV-2a and EBLV-2b [51][60]. The first occurs in the United Kingdom, Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, and Denmark, while the second includes the Finnish EBLV-2 strains and a strain from Switzerland [59], where the divergence of the Finnish strains from the Swiss strain occurred within the last 200 years [59].

3. Phylogeny of Bat Lyssaviruses

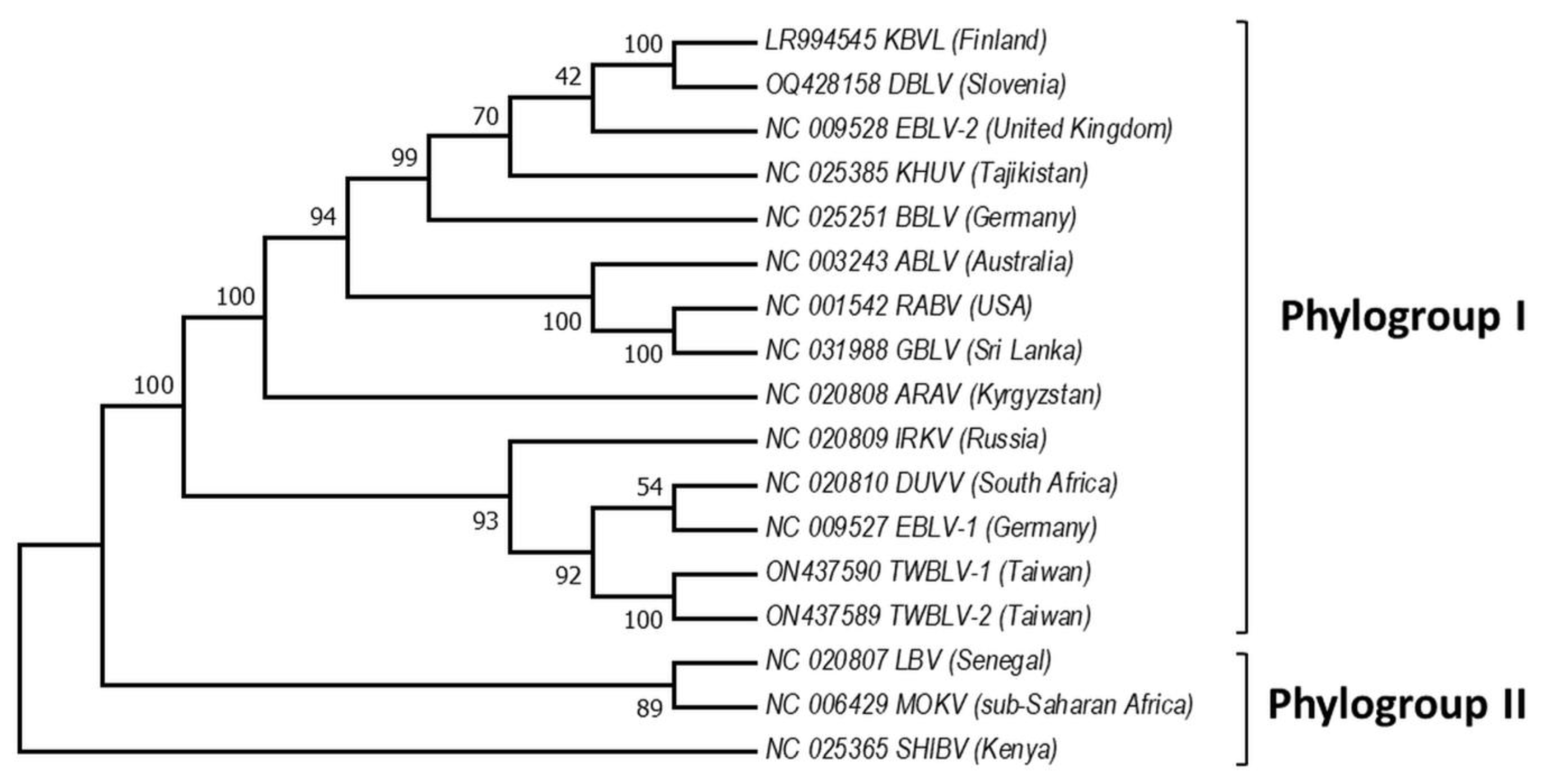

Based on the sequence analysis of the lyssavirus N gene, serologic cross-reactivity and pathogenicity bat lyssaviruses are divided into two phylogroups [48][61][62][63], https://ictv.global/report/chapter/rhabdoviridae/rhabdoviridae/lyssavirus and an unresolved but widely adopted third phylogroup [64][65], https://www.who-rabies-bulletin.org/site-page/classification which might contain some of the most divergent lyssaviruses (Figure 2). European viruses are included in Phylogroups I and group of lyssaviruses, which are highly divergent. Phylogroup II is discussed only as a potential scenario for cross-species bat transmission.

Figure 2. Phylogeny of bat lyssaviruses. The N + P + M + G + L coding regions of representative reference sequences of lyssaviruses used in the analysis were derived from Genbank. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and General Time Reversible model. There were a total of 568 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X. Virus names are: RABV—rabies virus, ARAV—Aravan virus, ABLV—Australian bat lyssavirus, BBLV—Bokeloh bat lyssavirus, DUVV—Duvenhage virus, EBLV-1—European bat lyssavirus 1, EBLV-2—European bat lyssavirus 2, GBLV—Gannoruwa bat lyssavirus, IKOV—Ikoma virus, IRKV—Irkut virus, KHUV—Khujand virus, LBV—Lagos bat virus, MOKV—Mokola virus, SHIBV—Shimoni bat virus, KBVL—Kotalahti bat lyssavirus, DBLV—Divača bat lyssavirus, TWBLV-1—Taiwan bat lyssavirus 1, and TWBLV-2—Taiwan bat lyssavirus 2.

Phylogroup I includes all these lyssaviruses RABV, ARAV, ABLV, BBLV, DUVV, EBLV-1, EBLV-2, GBLV, IRKV, KBLV, DBLV, KHUV, TWBLV-1, and TWBLV-2, whereas LBV, MOKV, and SHIBV form Phylogroup II [23][31][34][35][66][67][68][69]. Phylogenetically, the most divergent lyssaviruses LLEBV, IKOV, WCBV, and MBLV appear related [27][55][56][70]. Phylogroup I is divided into two major groups: the first includes the Palearctic lyssaviruses IRKV, EBLV-1, TWBLV-1, TWBLV-2 and African DUVV lyssaviruses and the second ARAV, BBLV, KHUV, and EBLV-2 which are also lyssaviruses with Palearctic distribution, as well as Australian—ABLV, Oriental—GBLV, and American—RABV [38]. Interestingly, EBLV-1 is most closely related to DUVV and IRKV, while EBLV-2 to KBLV, KHUV, and BBLV [30][32]. Based on the close phylogenetic relation between EBLV-1 and DUVV lyssaviruses [71], it is hypothesized that EBLV-1 originated in North Africa and spread to Europe (Iberian Peninsula) via the Strait of Gibraltar. However, Hayman et al. [13] present phylogenetic evidence based on the rabies N gene sequences that EBLV-1 and DUVV share a common ancestor with IRKV (isolate from Russia) and both have been transferred to Africa from the Palearctic region, and Europe in particular. Phylogenetic relationships in the most divergent lyssaviruses demonstrate close phylogenetic relatedness between the LLEBV virus from Spain, sub-Saharan Africa MBLV with the Eurasian WCBV and the African IKOV lyssavirus [34][37][72]. Genetically, LLEBV is more closely related to IKOV than to WCBV, in contrast with MBLV [34].

For a better understanding of lyssavirus phylogeny and their current distributions, a closer look at their bat species reservoirs is required. Generally, morphological keys such as Dietz et al. [73] are widely used for bat identification. On the other hand, morphological identification from carcasses can be limited due to the state of decomposition or nearly indistinguishable morphological features in juvenile bats and can lead to misidentifications [74]. Therefore, genetic markers are highly required due to their role for precise bat taxonomic clarification especially in cryptic species complexes, e.g., Çoraman et al. [75] and De Benedictis et al. [76]. Genomic and mitochondrial analyses have placed bats into two suborders: Yinpterochiroptera—including the five families in the superfamily Rhinolophoidea plus the flying foxes—Pteropodidae, and Yangochiroptera—including the three superfamilies: Emballonuroidea, Vespertilionoidea, and Noctilionoidae, comprising a total of 13 families. Two superfamilies (Rhinolophoidea and Vespertilionoidea) are of particular interest in Europe because their representatives are the main reservoir of lyssaviruses. The greater horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) (Rhinolophidae, Rhinolophoidea) and the Vespertilionoidea species Greater mouse-eared bat (Myotis myotis), Lesser mouse-eared bat (M. blythii), Natterer’s bat (M. nattereri), Serotine bat (Eptesicus serotinus), Meridional serotine (E. isabellinus), Common pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus), Nathusius’s pipistrelle (P. nathusii), Brown long-eared bat (Plecotus auritus), Common noctule (Nyctalus noctula), Parti-coloured bat (Vesperilio murinus) (Vespertilionidae), Common bent-wing bat (Miniopterus schreibersii) (Miniopteridae), and European free-tailed bat (Tadarida teniotis) (Molossidae) have all been documented as being infected by EBLV-1 [50][53][77][78][79]. The virus was also isolated from the Egyptian fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus) (Pteropodidae) in a Dutch zoo [80]. Regardless of the high number of bat hosts recorded for EBLV-1, EBLV-2 is restricted to Myotis daubentonii and M. dasycneme [49][50][51]. KBLV was found only in Myotis brandtii [23], BBLV only in M. nattereri [81][82], and DBLV only in M. capacinii [35]. For comparison, from those bat species, virus serological detection is provided on 15 bats (R. ferrumequinum, B. barbastellus, E. serotinus, M. blythii, M. brandtii, M. capaccinii, M. myotis, M. nattereri, N. noctule, P. nathusii, P. pipistrellus, P. auratus, M. schreibersii, T. teniotis, R. aegyptiacus), identification of viral species affiliation on 16 bats (R. ferrumequinum, E. isabellinus, E. serotinus, M. brandtii, M. capaccinii M. dasycneme, M. daubentoniid, M. myotis, M. nattereri, N. noctule, P. nathusii, P. pipistrellus, P. auratus, V. murinus, M. schreibersii, R. aegyptiacus) and both identified in 12 bat species (R. ferrumequinum, E. serotinus, M. brandtii, M. capaccinii, M. myotis, M. nattereri, N. noctule, P. nathusii, P. pipistrellus, P. auritus, M. schreibersii, R. aegyptiacus).

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/pathogens12091089

References

- Ruedi, M.; Stadelmann, B.; Gager, Y.; Douzery, E.J.; Francis, C.M.; Lin, L.K.; Guillén-Servent, A.; Cibois, A. Molecular phylogenetic reconstructions identify East Asia as the cradle for the evolution of the cosmopolitan genus Myotis (Mammalia, Chiroptera). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013, 69, 437–449.

- Teeling, E.C.; Vernes, S.C.; Dávalos, L.M.; Ray, D.A.; Gilbert, M.T.P.; Myers, E. Bat1K Consortium. Bat Biology, Genomes, and the Bat1K Project: To Generate Chromosome-Level Genomes for All Living Bat Species. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci 2018, 6, 23–46.

- Teeling, E.C.; Jones, G.; Rossiter, S.J. Phylogeny, genes, and hearing: Implications for the evolution of echolocation in bats. In Bat Bioacoustics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 25–54.

- Simmons, N.B.; Cirranello, A.L. Bat Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Database, Version 1.3. 2023. 2023. Available online: https://batnames.org/ (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Wackermannová, M.; Pinc, L.; Jebavý, L. Olfactory sensitivity in mammalian species. Physiol. Res. 2016, 65, 369.

- Wilkinson, G.S.; Adams, D.M.; Haghani, A.; Lu, A.T.; Zoller, J.; Breeze, C.E.; Arnold, B.D.; Ball, H.C.; Carter, G.G.; Cooper, L.N.; et al. Genome Methylation Predicts Age and Longevity of Bats. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1615.

- Shen, Y.-Y.; Liang, L.; Zhu, Z.-H.; Zhou, W.-P.; Irwin, D.M.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Hillis, D.M. Adaptive evolution of energy metabolism genes and the origin of flight in bats. PNAS 2010, 107, 8666–8671.

- Subudhi, S.; Rapin, N.; Misra, V. Immune System Modulation and Viral Persistence in Bats: Understanding Viral Spillover. Viruses 2019, 11, 192.

- Banerjee, A.; Baker, M.L.; Kulcsar, K.; Misra, V.; Plowright, R.; Mossman, K. Novel Insights into Immune Systems of Bats. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 26.

- Begeman, L.; Suu-Ire, R.; Banyard, A.C.; Drosten, C.; Eggerbauer, E.; Freuling, C.M.; Gibson, l.; Goharriz, H.; Horton, D.L.; Jennings, D.; et al. Experimental Lagos bat virus infection in straw-colored fruit bats: A suitable model for bat rabies in a natural reservoir species. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008898.

- Irving, A.T.; Ahn, M.; Goh, G.; Anderson, D.E.; Wang, L.F. Lessons from the host defences of bats, a unique viral reservoir. Nature 2021, 589, 363–370.

- Brook, C.E.; Dobson, A.P. Bats as ‘special’ reservoirs for emerging zoonotic pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 172–180.

- Hayman, D.T.S. Bats as viral reservoirs. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2016, 3, 77–99.

- Latinne, A.; Hu, B.; Olival, K.J.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Chmura, A.A.; Field, H.E.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Epstein, J.H.; et al. Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4235.

- EUROBATS. Action Plan for the Conservation of Bat Species in the European Union 2016–2021; Inf.EUROBATS.AC21.5; EUROBATS: Bonn, Germany, 2006.

- Teeling, E.C.; Springer, M.S.; Madsen, O.; Bates, P.; O’Brien, S.J.; Murphy, W.J. A molecular phylogeny for bats illuminates biogeography and the fossil record. Science 2005, 307, 580–584.

- Kohl, C.; Kurth, A. European bats as carriers of viruses with zoonotic potential. Viruses 2014, 6, 3110–3128.

- Smreczak, M.; Orłowska, A.; Marzec, A.; Trębas, P.; Müller, T.; Freuling, C.M.; Żmudziński, J.F. Bokeloh bat lyssavirus isolation in a Natterer’s bat, Poland. Zoonoses Public Health 2018, 65, 1015–1019.

- Vos, A.; Kaipf, I.; Denzinger, A.; Fooks, A.R.; Johnson, N.; Müller, T. European bat lyssaviruses—An ecological enigma. Acta Chiropt. 2007, 9, 283–296.

- Banyard, A.C.; Hayman, D.; Johnson, N.; McElhinney, L.; Fooks, A.R. Bats and lyssaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2011, 79, 239–289.

- Banyard, A.C.; Davis, A.; Gilbert, A.; Markotter, W. Bat Rabies. In Rabies: Scientific Basis of the Disease and Its Management, 4th ed.; Fooks, A.R., Jackson, A.C., Eds.; Chapter 7; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 231–276. ISBN 978-0-12-818705-0.

- Afonso, C.L.; Amarasinghe, G.K.; Bányai, K.; Bào, Y.; Basler, C.F.; Bavari, S.; Bejerman, N.; Blasdell, K.R.; Briand, F.X.; Briese, T.; et al. Taxonomy of the order Mononegavirales: Update 2016. Arch Virol. 2016, 161, 2351–2360.

- Nokireki, T.; Tammiranta, N.; Kokkonen, U.M.; Kantala, T.; Gadd, T. Tentative novel lyssavirus in a bat in Finland. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. J. 2018, 65, 593–596.

- Kuhn, J.H.; Adkins, S.; Agwanda, B.R.; Al Kubrusli, R.; Alkhovsky, S.V.; Amarasinghe, G.K.; Avšič-Županc, T.; Ayllón, M.A.; Bahl, J.; Balkema-Buschmann, A.; et al. Taxonomic update of phylum Negarnaviricota (Riboviria: Orthornavirae), including the large orders Bunyavirales and Mononegavirales. Arch Virol. 2021, 166, 3513–3566.

- Coertse, J.; Markotter, W.; Le Roux, K.; Stewart, D.; Sabeta, C.T.; Nel, L.H. New isolations of the rabies related Mokola virus from South Africa. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 37.

- Klein, A.; Calvelage, S.; Schlottau, K.; Hoffmann, B.; Eggerbauer, E.; Müller, T.; Freuling, C.M. Retrospective Enhanced Bat Lyssavirus Surveillance in Germany between 2018–2020. Viruses 2021, 13, 1538.

- Marston, D.A.; Horton, D.L.; Ngeleja, C.; Hampson, K.; McElhinney, L.M.; Banyard, A.C.; Haydon, D.; Cleaveland, S.; Rupprecht, C.E.; Bigambo, M.; et al. Ikoma lyssavirus, highly divergent novel lyssavirus in an African civet. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 664–667.

- Markotter, W.; Kgaladi, J.; Nel, L.H.; Marston, D.; Wright, N.; Coertse, J.; Müller, T.F.; Sabeta, C.T.; Fooks, A.R.; Freuling, C.M. Diversity and Epidemiology of Mokola Virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2511.

- Sabeta, C.T.; Markotter, W.; Mohale, D.K.; Shumba, W.; Wandeler, A.I.; Nel, L.H. Mokola virus in domestic mammals, South Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 1371–1373.

- Rupprecht, C.; Kuzmin, I.; Meslin, F. Lyssaviruses and rabies: Current conundrums, concerns, contradictions and controversies. F1000Research 2017, 6, 184.

- Hu, S.; Hsu, C.; Lee, M.; Tu, Y.; Chang, J.; Wu, C.; Lee, S.-H.; Ting, L.-J.; Tsai, K.-R.; Cheng, M.-C.; et al. Lyssavirus in Japanese Pipistrelle, Taiwan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 782–785.

- Calvelage, S.; Tammiranta, N.; Nokireki, T.; Gadd, T.; Eggerbauer, E.; Zaeck, L.M.; Potratz, M.; Wylezich, C.; Höper, D.; Müller, T.; et al. Genetic and Antigenetic Characterization of the Novel Kotalahti Bat Lyssavirus (KBLV). Viruses 2021, 13, 69.

- Hu, S.-C.; Hsu, C.-L.; Lee, F.; Tu, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-W.; Chang, J.-C.; Hsu, W.-C. Novel Bat Lyssaviruses Identified by Nationwide Passive Surveillance in Taiwan, 2018–2021. Viruses 2022, 14, 1562.

- Coertse, J.; Grobler, C.S.; Sabeta, C.T.; Seamark, E.C.J.; Kearney, T.; Paweska, J.T.; Markotter, W. Lyssaviruses in Insectivorous Bats, South Africa, 2003-2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 3056–3060.

- Černe, D.; Hostnik, P.; Toplak, I.; Presetnik, P.; Maurer-Wernig, J.; Kuhar, U. Discovery of a novel bat lyssavirus in a Long-fingered bat (Myotis capaccinii) from Slovenia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023, 17, e0011420.

- Nel, L.H.; Rupprecht, C.E. Emergence of lyssaviruses in the Old World: The case of Africa. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007, 315, 161–193.

- Hayman, D.T.S.; Fooks, A.R.; Marston, D.A.; Garcia-R, J.C. The Global Phylogeography of Lyssaviruses—Challenging the ‘Out of Africa’ Hypothesis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0005266.

- Longdon, B.; Murray, G.G.; Palmer, W.J.; Day, J.P.; Parker, D.J.; Welch, J.J.; Obbard, D.J.; Jiggins, F.M. The evolution, diversity, and host associations of rhabdoviruses. Virus Evol. 2015, 1, vev014.

- Li, C.X.; Shi, M.; Tian, J.H.; Lin, X.D.; Kang, Y.J.; Chen, L.; Qin, X.C.; Xu, J.; Holmes, E.C.; Zhang, Y.Z. Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses. Elife 2015, 29, e05378.

- Walker, P.J.; Firth, C.; Widen, S.G.; Blasdell, K.R.; Guzman, H.; Wood, T.G.; Paradkar, P.N.; Holmes, E.; Tesh, R.B.; Vasilakis, N. Evolution of genome size and complexity in the Rhabdoviridae. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004664.

- Velasco-Villa, A.; Mauldin, M.R.; Shi, M.; Escobar, L.E.; Gallardo-Romero, N.F.; Damon, I.; Olson, V.A.; Streicker, D.G.; Emerson, G. The history of rabies in the Western Hemisphere. Antivir. Res. 2017, 146, 221–232.

- Caraballo, D.A.; Lema, C.; Novaro, L.; Gury-Dohmen, F.; Russo, S.; Beltrán, F.J.; Palacios, G.; Cisterna, D.M. A Novel Terrestrial Rabies Virus Lineage Occurring in South America: Origin, Diversification, and Evidence of Contact between Wild and Domestic Cycles. Viruses 2021, 13, 2484.

- Singh, R.; Singh, K.P.; Cherian, S.; Saminathan, M.; Kapoor, S.; Manjunatha Reddy, G.B.; Panda, S.; Dhama, K. Rabies–epidemiology, pathogenesis, public health concerns and advances in diagnosis and control: A comprehensive review. Vet. Q. 2017, 37, 212–251.

- Potratz, M.; Zaeck, L.M.; Weigel, C.; Klein, A.; Freuling, C.M.; Müller, T.; Finke, S. Neuroglia infection by rabies virus after anterograde virus spread in peripheral neurons. ANC 2020, 8, 1–15.

- Baghi, H.B.; Rupprecht, C. Notes on three periods of rabies focus in the Middle East: From progress during the cradle of civilization to neglected current history. Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 697–703.

- Badrane, H.; Tordo, N. Host switching in Lyssavirus history from the chiroptera to the carnivora orders. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 8096–8104.

- Rupprecht, C.E.; Turmelle, A.; Kuzmin, I.V. A perspective on lyssavirus emergence and perpetuation. COVIRO 2011, 1, 662–670.

- Badrane, H.; Bahloul, C.; Perrin, P.; Tordo, N. Evidence of two Lyssavirus phylogroups with distinct pathogenicity and immunogenicity. Virol. J. 2001, 75, 3268–3276.

- Fooks, A.; Brookes, S.; Johnson, N.; McElhinney, L.; Hutson, A. European bat lyssaviruses: An emerging zoonosis. Epidemiol. Infect. 2003, 131, 1029–1039.

- Schatz, J.; Fooks, A.R.; McElhinney, L.; Horton, D.; Echevarria, J.; Vázquez-Moron, S.; Kooi, E.A.; Rasmussen, T.B.; Müller, T.; Freuling, C.M. Bat rabies surveillance in Europe. Zoonoses Public Health 2012, 60, 22–34.

- McElhinney, L.M.; Marston, D.A.; Wise, E.L.; Freuling, C.M.; Bourhy, H.; Zanoni, R.; Moldal, T.; Kooi, E.A.; Neubauer-Juric, A.; Nokireki, T.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology and Evolution of European Bat Lyssavirus 2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 156.

- Šimić, I.; Lojkić, I.; Krešić, N.; Cliquet, F.; Picard-Meyer, E.; Wasniewski, M.; Ćukušić, A.; Zrnčić, V.; Bedeković, T. Molecular and serological survey of lyssaviruses in Croatian bat populations. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 274.

- Seidlova, V.; Zukal, J.; Brichta, J.; Anisimov, N.; Apoznański, G.; Bandouchova, H.; Bartonička, T.; Berková, H.; Botvinkin, A.D.; Heger, T.; et al. Active surveillance for antibodies confirms circulation of lyssaviruses in Palearctic bats. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 482.

- Kuzmin, I.V.; Hughes, G.J.; Botvinkin, A.D.; Orciari, L.A.; Rupprecht, C.E. Phylogenetic relationships of Irkut and West Caucasian bat viruses within the Lyssavirus genus and suggested quantitative criteria based on the N gene sequence for lyssavirus genotype definition. Virus Res. 2005, 111, 28–43.

- Freuling, C.M.; Beer, M.; Conraths, F.J.; Finke, S.; Hoffmann, B.; Keller, B.; Kliemt, J.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Mühlbach, E.; Teifke, J.P.; et al. Novel lyssavirus in natterer’s bat, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1519–1522.

- Ceballos, N.; Morón, S.; Berciano, J.M.; Nicolás, O.; López, C.; Juste, J.; Nevado, C.; Setién, A.A.; Echevarría, J.E. Novel Lyssavirus in Bat, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013, 19, 793–795.

- Davis, P.L.; Holmes, E.C.; Larrous, F.; Van der Poel, W.H.; Tjørnehøj, K.; Alonso, W.J.; Bourhy, H. Phylogeography, population dynamics, and molecular evolution of European bat lyssaviruses. Virol. J. 2005, 79, 10487–10497.

- Mingo-Casas, P.; Sandonis, V.; Obón, E.; Berciano, J.M.; Vázquez-Morón, S.; Juste, J.; Echevarria, J.E. First cases of European bat lyssavirus type 1 in Iberian serotine bats: Implications for the molecular epidemiology of bat rabies in Europe. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018, 12, e0006290.

- Jakava-Viljanen, M.; Nokireki, T.; Sironen, T.; Vapalahti, O.; Sihvonen, L.; Liisa, S.; Huovilainen, A. Evolutionary trends of European bat lyssavirus type 2 including genetic characterization of Finnish strains of human and bat origin 24 years apart. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 1489–1498.

- Harris, S.L.; Aegerter, J.N.; Brookes, S.M.; McElhinney, L.M.; Jones, G.; Smith, G.C.; Fooks, A.R. Targeted surveillance for European bat lyssaviruses in English bats (2003-06). J. Wildl. Dis. 2009, 45, 1030–1041.

- Kuzmin, I.V.; Orciari, L.A.; Arai, Y.T.; Smith, J.S.; Hanlon, C.A.; Kameoka, Y.; Rupprecht, C.E. Bat lyssaviruses (Aravan and Khujand) from Central Asia: Phylogenetic relationships according to N, P and G gene sequences. Virus Res. 2003, 97, 65–79.

- Kuzmin, I.V.; Novella, I.S.; Dietzgen, R.G.; Padhi, A.; Rupprecht, C.E. The rhabdoviruses: Biodiversity, phylogenetics, and evolution. Infect Genet Evol. 2009, 9, 541–553.

- Delmas, O.; Holmes, E.C.; Talbi, C.; Larrous, F.; Dacheux, L.; Bouchier, C.; Bourhy, H. Genomic diversity and evolution of the lyssaviruses. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2057.

- Fooks, A.R.; Cliquet, F.; Finke, S.; Freuling, C.; Hemachudha, T.; Mani, R.S.; Müller, T.; Nadin-Davis, S.; Picard-Meyer, E.; Wilde, H.; et al. Rabies. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17091.

- Vega, S.; Lorenzo-Rebenaque, L.; Marin, C.; Domingo, R.; Fariñas, F. Tackling the Threat of Rabies Reintroduction in Europe. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 7, 613712.

- Tjørnehøj, K.; Fooks, A.R.; Agerholm, J.S.; Rønsholt, L. Natural and experimental infection of sheep with European bat lyssavirus type-1 of Danish bat origin. J. Comp. Pathol. 2006, 134, 190–201.

- Schatz, J.; Freuling, C.M.; Auer, E.; Goharriz, H.; Harbusch, C.; Johnson, N.; Kaipf, I.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Mühldorfer, K.; Mühle, R.-U.; et al. Enhanced Passive Bat Rabies Surveillance in Indigenous Bat Species from Germany—A Retrospective Study. PLoS Negl. Trop Dis. 2014, 8, e2835.

- Gunawardena, P.S.; Marston, D.A.; Ellis, R.J.; Wise, E.L.; Karawita, A.C.; Breed, A.C.; Fooks, A.R. Lyssavirus in Indian flying foxes Sri Lanka. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 1456–1459.

- Kuzmin, I.V.; Mayer, A.E.; Niezgoda, M.; Markotter, W.; Agwanda, B.; Breiman, R.F.; Rupprecht, C.E. Shimoni bat virus, a new representative of the Lyssavirus genus. Virus Res. 2010, 149, 197–210.

- Kuzmin, I.V.; Bozick, B.; Guagliardo, S.A.; Kunkel, R.; Shak, J.R.; Tong, S.; Rupprecht, C.E. Bats, emerging infectious diseases, and the rabies paradigm revisited. Emerg. Health. Threats. J. 2011, 4, 1.

- Amengual, B.; Whitby, J.E.; King, A.; Cobo, J.S.; Bourhy, H. Evolution of European bat lyssaviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 1997, 78, 2319–2328.

- Kuzmin, I.V.; Rupprecht, C.E. Bat Lyssaviruses. In Bats and Viruses: A New Frontier of Emerging Infectious Diseases; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 47–97.

- Dietz, C.; von Helversen, O.; Nill, D. Bats of Britain. Europe and Northwest Africa; A and C Black: London, UK, 2009; 400p.

- Arnaout, Y.; Djelouadji, Z.; Robardet, E.; Cappelle, J.; Cliquet, F.; Touzalin, F.; Jimenez, G.; Hurstel, S.; Borel, C.; Picard-Meyer, E. Genetic identification of bat species for pathogen surveillance across France. PLoS ONE 2022, 4, e0261344.

- Çoraman, E.; Dundarova, H.; Dietz, C.; Mayer, F. Patterns of mtDNA introgression suggest population replacement in Palaearctic whiskered bat species. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 191805.

- De Benedictis, P.; Leopardi, S.; Markotter, W.; Velasco-Villa, A. The Importance of Accurate Host Species Identification in the Framework of Rabies Surveillance, Control and Elimination. Viruses 2022, 14, 492.

- Serra-Cobo, J.; Amengual, B.; Abellan, C.; Bourhy, H. European bat Lyssavirus infection in Spanish bat populations. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 413–420.

- Picard-Meyer, E.; Dubourg-Savage, M.J.; Arthur, L.; Barataud, M.; Bécu, D.; Bracco, S.; Borel, C.; Larcher, G.; Meme-Lafond, B.; Moinet, M.; et al. Active surveillance of bat rabies in France: A 5-year study (2004–2009). Vet Microbiol. 2011, 151, 390–395.

- Echevarria, J.E.; Avellon, A.; Juste, J.; Vera, M.; Ibayez, C. Screening of active lyssavirus infection in wild bat populations by viral RNA on oropharyngeal swabs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 3678–3683.

- Coxon, C.; McElhinney, L.; Pacey, A.; Gauntlett, F.; Holland, S. Preliminary Outbreak Assessment: Rabies in a Cat in Italy. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Animal and Plant Health Agency, Advice Services—International Disease Monitoring. 2020. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/897070/rabies-cat-italy-poa.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Puechmaille, S.J.; Allegrini, B.; Boston, E.S.; Dubourg-Savage, M.-J.; Evin, A.; Knochel, A.; Le Bris, Y.; Lecoq, V.; Lemaire, M.; Rist, D.; et al. Genetic analyses reveal further cryptic lineages within the Myotis nattereri species complex. Mamm. Biol. 2012, 77, 224–228.

- Parize, P.; Travecedo Robledo, I.C.; Cervantes-Gonzalez, M.; Kergoat, L.; Larrous, F.; Serra-Cobo, J.; Dacheux, L.; Bourhy, H. Circumstances of Human–Bat interactions and risk of lyssavirus transmission in metropolitan France. Zoonoses Public Health 2020, 67, 774–784.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!