Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Architecture And Design

There are strong indications that the built environment has had a great influence on the course of the COVID-19 pandemic and the post-disaster recovery. The COVID-19 pandemic has adversely affected both human and global development, while efforts to combat this menace call for an integrated human social capital index.

- human social capital

- built environment

- COVID-19 pandemic

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic that emerged in 2019 has impacted current people’s health status, the economy, and the general growth of the built environment. The pandemic has been the worst for decades; addressing its impacts from the built environment viewpoint is important for driving urban regeneration. Consequently, researchers worldwide are attempting to find the most constructive and productive means of managing the pandemic and limiting its negative impacts [1,2,3]. The relationship between human interaction, built environments, and the COVID-19 pandemic is paramount to this ongoing debate [2,4].

The built environment, according to [2,4], refers to the human-made physical surroundings in which people live, work, and interact. It encompasses all the structures, spaces, and systems humans create, such as buildings, roads, parks, transportation networks, utilities, and other infrastructure elements. The built environment, which results from human planning, design, construction, and development, plays a significant role in shaping the quality of life, social interactions, and overall well-being of individuals and communities. In view of the COVID-19 pandemic, resilience is an important tool for evaluating urban ecosystems’ capacity to adjust to shifting circumstances and meet environmental targets. The notion of resilience has garnered attention across diverse fields since the early 1900s, yet its exploration within the built environment remains limited [5,6]. Within the context of this research, resilience in the built environment is construed in terms of the capacity of a neighbourhood to recover from stresses and pressures while simultaneously fostering constructive adaptation and evolution toward sustainability. The theoretical idea of built-environmental resilience has grown in popularity in recent years, owing to the growing frequency and severity of global disasters [6,7,8]. This has resulted in the need for a more thorough and holistic method for comprehending the numerous aspects that contribute to built-environmental resilience [9,10].

A handful of studies since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic have documented the significance of resilience in the built environment and the relevance of human social capital in recovering from catastrophes [11,12,13]. These studies describe built-environmental resilience as the capacity of communities and structures to endure, recover, and adapt to numerous hazards such as natural catastrophes, climate change, socioeconomic disturbances, and COVID-19 [14,15,16]. Other urban hazards that call for resilience include the increasing urban population, which has adversely affected both the environment and the residents of cities [6,14,17]. However, the global COVID-19 pandemic is currently the greatest challenge [18,19].

Human social capital encompasses the assets and values that emerge from interactions between people and interactions with the built environment. Its function in building resilience has attracted a great deal of interest in recent years [9,19,20]. Resilience is crucial for a successful community response to the problems posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The significance of COVID-19’s effect on the built environment cannot be overemphasised. The COVID-19 pandemic has broadened the human horizon by altering people’s behaviour and use of the built environment [21,22]. The link between the built environment and the COVID-19 pandemic must receive appropriate attention to foster the potential adaptive construction of cities.

2. Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Recovery

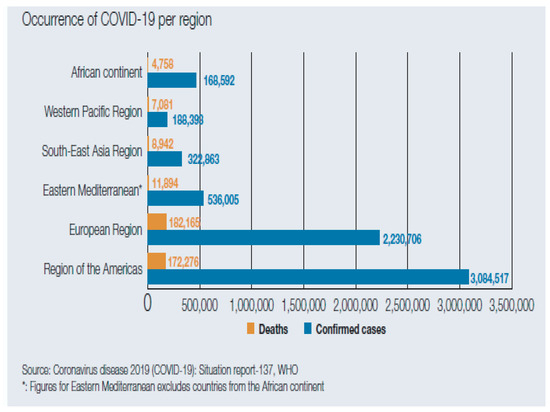

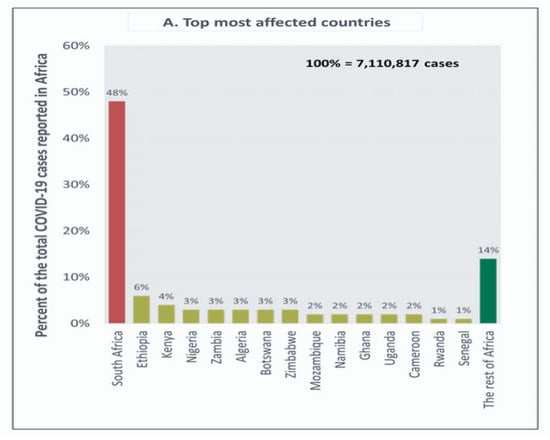

The COVID-19 pandemic caused deaths across the globe [27], and the African Continent was not spared [28], as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. These had enormous consequences for communities and economies, resulting in extensive social, economic, and health implications. Under these circumstances, the significance of social capital in facilitating recovery has grown in importance. Several research efforts have already shown the significance of social capital and cooperation among individuals and groups to overcome challenges [20,25,27]. Some literature substantiates that social capital can help achieve resilience after the pandemic [8,28,29], and facilitate communities’ adaptation goals after catastrophes. Social capital has become vital in assisting communities to cope with the pandemic’s effects and build resilience. There is a need for coordination and cooperation to assist those most affected by the pandemic’s social and economic effects [30,31,32].

In disaster and emergency research, resilience and vulnerability are increasingly studied alongside social capital [33,34,35]. Before and after a crisis, social capital influences resilience and vulnerability. It is often used to assess people’s potential to recover from disasters [8,36,37]. Simply put, social capital includes the moral codes, principles, confidence, and connections of communities. The term also embraces social organisations in which members of society help one another, thus boosting urban communities and lessening dependence on the state. These organisations may possess analytics and insights for group cohesion and enhancing cooperation and collaboration in the face of disasters.

Figure 1. COVID-19 pandemic occurrence across the globe. Source: [38].

Figure 2. The African countries most significantly impacted by COVID-19. Source: [38].

3. Resilience, Human Social Capital, and the Built Environment

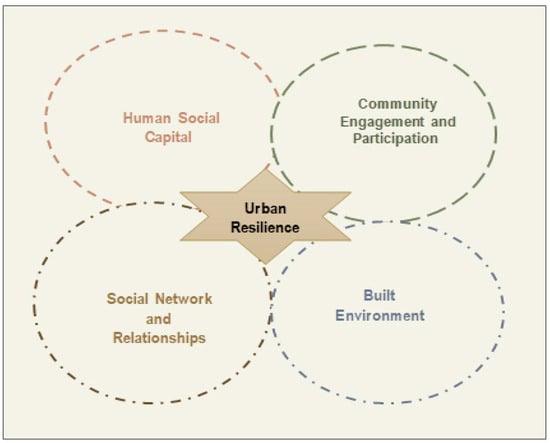

Resilience is described as the capacity to absorb disruptive changes while recognising and capitalising on opportunities [39,40,41]. In line with this assertion, Ref. [40] introduced the concept of resilience as a series of adaptive abilities that guide positive functioning following a disturbance. These studies inferred that resilience is not only an ultimate result but also an intermediary process in the form of adaptive capacity to achieve desired results. In the context of the built environment, resilience is considered to be a city’s capability to endure while recovering from natural disasters, economic shocks, and other disruptive events. Human social capital is the value derived from social networks, relationships, and interactions between people. It is essential in the built environment for building resilient communities after disruptive events. There are several ways in which resilience and human social capital are interconnected in the built environment, namely:

- (i)

-

Building social networks and relationships: Social capital entails forming relationships between individuals and groups. These networks and relationships can be leveraged in times of crisis to provide support and resources to those who need them [37].

- (ii)

- (iii)

-

Fostering trust and cooperation: Trust and cooperation are essential for building social capital and promoting resilience in the built environment. When individuals and groups trust each other and cooperate, they will recover better from disruptive events [25].

- (iv)

-

Encouraging knowledge sharing and learning: Resilient communities gain insight from previous difficulties and adapt their approaches to potential challenges. Social capital is essential for promoting knowledge sharing and learning among individuals and groups within the neighbourhood [43].

The interplay between urban resilience, human social capital, and the built environment is presented in Figure 3, as adapted from the study of [25,39,43]. By building strong social networks and relationships, promoting community engagement and participation, fostering trust and cooperation, and encouraging knowledge sharing and learning, communities can become more resilient and adapt to disruptive events.

4. Consolidating a Resilient Built Environment Using Human Social Capital

The built environment comprises the structural, ecological, and socio-cultural capital represented by man-made buildings and infrastructure. The built environment’s resilience is crucial in light of the growing frequency and severity of natural catastrophes and other stressors such as climate change and socioeconomic disturbances. A resilient built environment is characterised by a structure’s ability to endure and adapt to various shocks. Accomplishing this level of resilience necessitates the skill and knowledge to consider multiple social, economic, and technical aspects.

The idea of resilience provides a way to manage the protracted adaptation of the built environment and investigate the impacts of ecological changes on the effectiveness of various planning, design, and management approaches. In consequence, resilience is a conceptual and modelling framework that identifies the processes that help or hinder the attainment of sustainable environmental objectives. Resilience has three components: (i) the term’s core description, the capacity to withstand or recover from difficulties; (ii) models for translating the ambiguously defined core concept to specific situations; and (iii) an analogy for the social and private assumptions, experiences, and values associated with the theory. Social capital is one major aspect progressively recognised as important for generating resilience in the built environment. Trust and reciprocity rules can increase individuals’ desire to cooperate and contribute to the collective good [29,43].

Human social capital is important in fostering resilience because it provides individuals and communities with the resources to cope with adversity. It can improve access to resources, facilitate risk reduction and adaptation, and improve communities’ ability to respond to catastrophes [28,37,44]. Social networks can provide emotional support, information, and access to resources to help people overcome challenges and bounce back from setbacks. Strong social connections can also help build trust and cooperation, which are essential for effective collaboration and problem-solving [25]. This entails integrating social, economic, and technological aspects, as well as addressing inter-generational justice in creating resilience. Despite growing recognition of the value of social capital for resilience, incorporating social capital into the physical environment’s design is still in its early stages. The difficulty in measuring and quantifying social capital and the necessity to address power dynamics and inequality within communities are some of the obstacles and limitations of employing social capital as a resilience-building method [32,36,44].

A rising corpus of research on resilience in the built environment has underlined the necessity for a systems approach that takes into account the interconnections between diverse elements. The built environment, which refers to the physical surroundings in which people live and work, also significantly promotes resilience. The design and layout of buildings, neighbourhoods, and cities influence the social interactions and relationships that occur within them. For example, mixed-use developments that combine residential and commercial spaces can promote social interaction and community engagement, while poorly designed neighbourhoods with few public spaces and amenities can result in social exclusion and disengagement [25].

The built environment can also impact resilience due to its ability to adapt to environmental disasters and other disruptions. Resilient infrastructure, such as buildings, roads, and energy systems, can help minimise the consequences of catastrophes and ensure that communities recover more quickly after a crisis. Consequently, the resilience concept relates to both human social capital and the built environment. Building strong social connections and creating resilient infrastructure may assist people and communities in adapting to and recovering from adversity, while poorly designed environments and weak social networks can hinder resilience and exacerbate the impact of stress and trauma.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/urbansci7040114

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!