Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Renewable energy strategies for sustainable development perform as best practices and strategic insights necessary to support large scale organizations’ approach to sustainability. Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) enhance the value of such initiatives. A renewable PPA contract delivers green energy efficiently to organizations that seek sustainability benefits. Consequently, various approaches that define PPAs are utilized to motivate both interested parties to participate in such deals.

- PPAs

- sustainability

- indicators

- MCDA

- renewables

- construction

1. Introduction

Organizations are progressively attempting to lower their environmental impact and energy costs, which aligns with the global sustainability-oriented trend. As an approach to such an initiative, many organizations and corporates are sourcing energy from renewable generation sources (RES). Renewable energy is gradually being raised from operational and technical activity to a strategic and commercial focus in an organization’s energy strategy. Corporates may implement a renewable energy plan in a variety of ways, including renewable power, heat, and transportation, all of which have connected benefits [1][2].

Renewable electricity solutions involve either directly constructing an asset, or acquiring green power from a third party’s project, both of which make it possible to obtain renewable energy certificates [3][4]. Corporate power purchase agreements (PPAs) have been proven a fitting tool for addressing sustainable initiatives, development risks, and finance opportunities. They may, therefore, help considerably in enhancing and expediting the deployment of renewables [5].

The renewable corporate sourcing sector in Europe, which includes both PPAs and other kinds of corporate sourcing, has enormous potential. Long-term PPAs are used by renewable energy plant developers to ensure a project’s future revenue and provide lenders with assurance that loans will be returned; in other words, to improve a project’s bankability in the absence of predictable income from government assistance programs [6][7]. However, these PPAs come with a lot of risks that most corporates are not familiar with [8]. Traditionally, utilities with a strong grasp of the energy market and broad, diversified portfolios of projects and technology have managed to cope with the risks associated with long-term energy contracts in Europe. They have had to devise complex procedures in order to accommodate an increasing proportion of fluctuating renewable energy costs. Corporates are increasingly interested in signing long-term PPAs as renewables become the primary energy technology for big energy corporations and new renewable energy suppliers enter the market. It is crucial that they realize the risks to which they may be exposed. During the last few years, different pricing PPA mechanisms have been explored by counterparties. However, fixed-price structures have dominated amongst commercial pricing mechanisms for renewable PPAs. The unpredictability of the wholesale power prices across Europe and the probability of additional price cannibalization of wind and solar capture prices by means of increased renewable penetration in the system is of the essence for developing new PPA structures. A vast number of offtakers are becoming more interested in alternate PPA pricing scenarios [9][10].

PPAs can also be conducted through various energy storage management strategies, used to mitigate energy consumption. Organizations can acquire storage capacity to supplement their renewable energy purchases using battery PPAs. By incorporating batteries into a renewable project, surplus energy can be stored during periods of high production and low power prices and sold back to the grid during times of low production and high-power prices. There are two categories of battery storage power purchase agreements (PPAs): a combined PPA that covers both renewable energy (usually from solar) and energy storage, and a separate PPA contract that only focuses on battery storage. There are two major categories of battery storage PPAs, namely, a combined PPA that covers both renewable energy (usually from solar) and energy storage, and a separate PPA contract that only focuses on battery storage [11][12]. A battery storage PPA that is structured accurately to reflect both the RES producer’s and the offtaker’s needs can reap pricing benefits. The seller can secure a stable revenue stream to support project financing, while the buyer gains an effective hedge against battery storage price fluctuations. Additionally, there are advantages in terms of reduced need for balancing and shaping during unpredictable output periods, as the battery can take over. This will make power more environmentally friendly by reducing reliance on purchasing fossil-fuel-based electricity from the grid during low production periods. Sustainability-related strategies can also be formulated via the implementation of such schemes. Thus, there is further impetus for increased storage to ensure availability of green power at all times of day [13][14].

2. Sustainable Energy Strategies for Power Purchase Agreements

Recent studies and reports have highlighted the importance of conducting more PPA deals in order to attain a sustainable society [9][15][16]. The corporate sourcing business in Europe has exploded in recent years. During 2014, the European corporate PPA market developed to a total capacity of more than 8 GW for offsite projects. In 2018, contracts for commercial and industrial onsite renewables totaled 1.3 GW and 2.1 GW, respectively. Over 2.5 GW of offsite PPAs were signed in 2019 alone [17]. The need for sustainability, as expressed through renewable energy projects, arises from a shortage of natural resources, leading the whole PPA theme to new insights and scientific “green” solutions [6]. Corporates act on several motives for trying to obtain power from renewables, but the capability of stabilizing energy costs is crucial for PPA transactions. While decarbonization obligations are frequently highlighted as the initial impetus for considering renewable corporate sourcing, most corporates identify the capacity of a PPA to minimize energy cost volatility and provide long-term savings on energy bills as the critical business justification [18].

Long-term PPAs, the most common agreements, vary between 10 and 15 years, are used by RES developers to ensure the project’s future revenue, and provide lenders a guarantee that their loans will be refunded in order to enhance the project’s feasibility (bankability of the project) in the event of the absence of governmental funding [19]. Nevertheless, risks still exist (e.g., development, volume, performance, etc.), and PPAs can become problematic for both counterparties, as these kinds of deals are brand-new to practitioners [20].

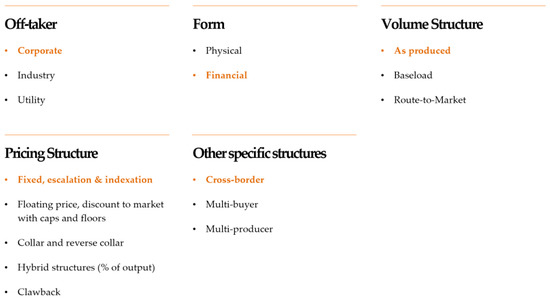

PPAs can be introduced into a wide variety of schemes depending on the counterparties’ needs and purposes. The accounting aspect of this sort of transaction also may be complicated, causing the PPA signing procedure to be delayed. The impact on financial statements may be severe, depending on how the agreement is constructed. PPAs can be categorized depending on the offtaker, energy transmission, volume produced, the chosen price mechanism, number of counterparties, and location of markets. Figure 1 presents the most common types of PPAs and highlights in orange and bold printing the most used types in European markets as extracted from interviewees’ expertise along with relevant publicly available reports and articles [17][21][22].

Figure 1. Main PPA types.

The needs between corporates, industries, and utilities usually vary and are typically explored on a case-by-case basis by practitioners. In most cases, offtakers are interested in implementing sustainability strategies, meaning reducing CO2 emissions and making environmental claims, contributing to society-related concerns, and achieving financial benefits (TBL). They usually have specific energy needs and seek a PPA with a tailored volume and price structure. Furthermore, contract clauses may vary, depending on the sustainability focus they want to reveal in the PPA deal [5].

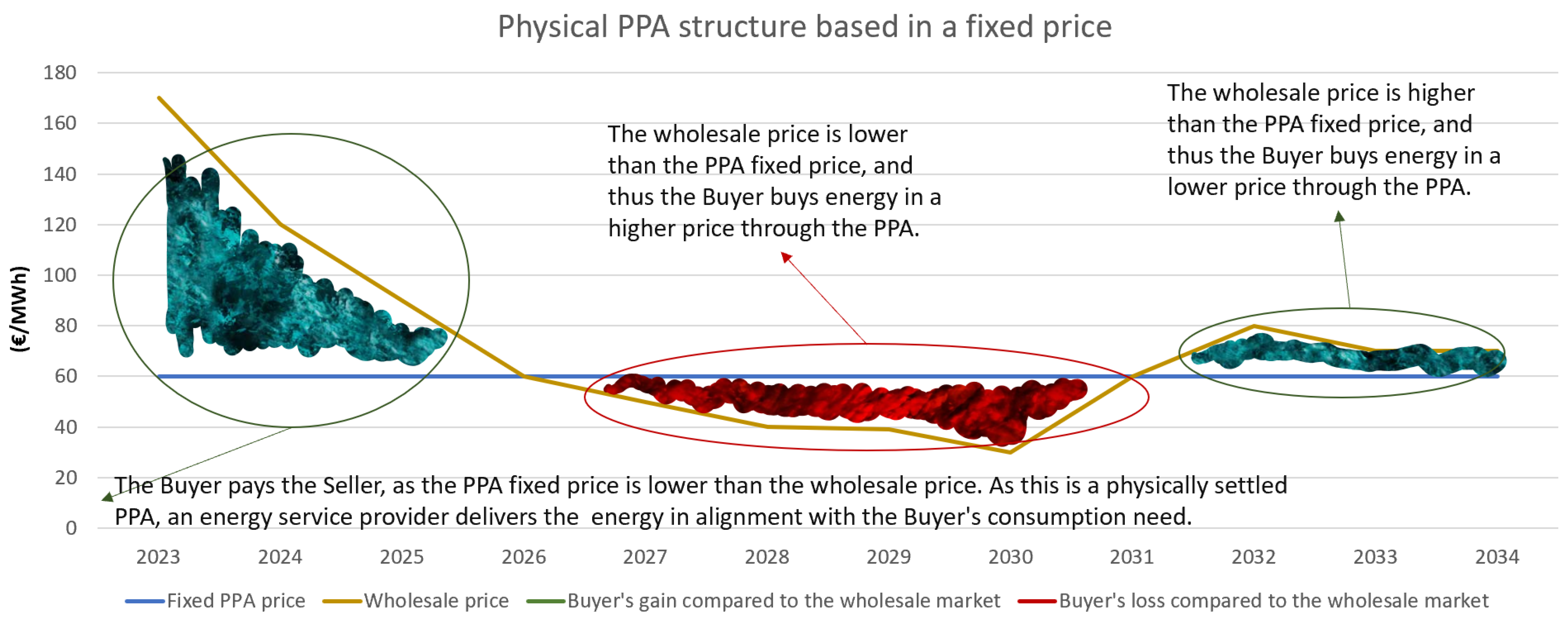

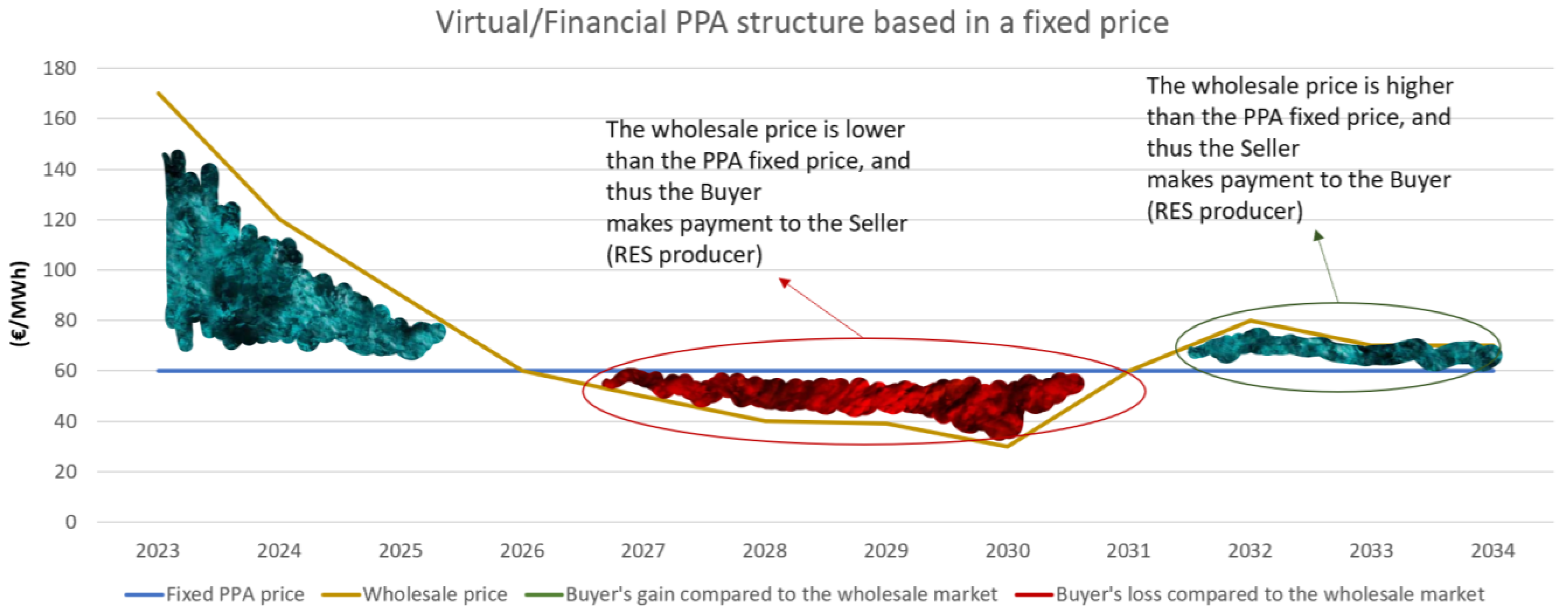

Physical PPAs represent a direct relationship between the offtaker and the RES producer, implying that the latter physically delivers the specified energy volume with the help of an energy provider (Figure 2). Virtual/financial PPAs (VPPAs), on the other hand, offer options to offtakers regardless of geographical distance. In these VPPAs, no physical energy exchange is involved, and it mainly includes a net cash settlement of the difference between the market spot price (wholesale market), and PPA agreed/fixed price (Figure 3). VPPAs may be typically used for hedging strategies against future spot price fluctuations [5][23].

Figure 2. Physical PPA following a fixed price scenario.

Figure 3. Virtual/financial PPA following a fixed price scenario.

Pay-as-produced (PAP) volume structures refer to PPAs in which a fixed tariff is paid for the energy produced, regardless of current or future market prices. It can cover all of the production or a percentage. PAP PPAs tend to be the most popular volume structure across Europe, offering a perfect alternative for the financial security subsidy schemes that may be inclined to fade. RES producers transfer key PPA risks (price, cannibalization, and profile) to the offtaker [24]. However, in regions with the most active growth of renewables capacity, offtakers are finding PAP contracts less attractive, and baseload PPAs are the next phase of commercial PPA structures. Baseload PPA structures offer a fixed delivery production profile. They can be defined in an annual or a monthly profile and are usually chosen from RES producers and off-takers seeking a fixed delivery energy profile. Such a structure includes specific production for each hour of the year/month, constantly throughout the agreed term [25]. A route-to-market strategy is a commercially motivated way of reaching, selling, and transacting to increase revenue and profit within a defined target market or segment. In the route-to-market volume structure, the offtaker bears the volume risk, and there are no delivery profile commitments; the RES producer will receive a lower price for the electricity provided compared to a fixed-volume PPA. Route-to-market PPAs are often addressed to a utility with power trading capabilities [26].

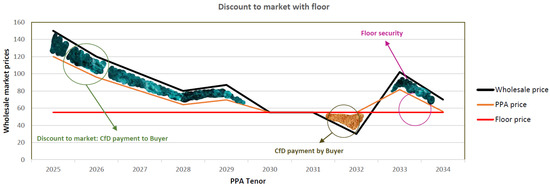

Using a fixed scheme combined with an escalation and–indexation structure, the researchers address the scenario in which the offtaker secures a starting power price that remains the same or, in most cases, rises/decreases according to a contractual profile. The phases can be determined in nominal terms, not including inflation as measured by changes in consumer price index (CPI) in terms of the annual growth rate and in index, or in factual terms by adding inflation indexation. As an alternative, a straightforward predetermined percentage increase/decrease every year may be used. Floating price, market discount with caps and floors introduces a pricing structure in which the offtaker attains a market discount (set percentage or amount) throughout the PPA tenor. In return, the offtaker offers the power producer with a floor or cap price, ensuring a minimum/maximum price for plant output and safeguarding the project’s bankability. This structure is based on a similar approach to the VPPA, under which the parties’ energy payments are subject to the wholesale market price and follow the approach of a contract for difference (CfD) mechanism (Figure 4). Collar and reverse-collar structures present a key difference to the previous structure, which is that there is no discount to market. A collar requires a project to assume more wholesale energy price risk that the offtaker is liable to (minimum and maximum price defined). The RES producer becomes the party at risk whenever the wholesale market price falls below the defined floor price but, in exchange, the producer benefits from an upside when the power market exceeds the defined cap. PPAs that follow this pricing structure express parties’ desire to constrain the volatility of power prices. However, high floor prices can potentially result in a higher agreed PPA strike price. Hybrid structures (% of output) contain a fixed percentage of the production of the RES plant (e.g., 80%) which is contracted at a fixed price. The remaining percentage of the output (e.g., 20%) is contracted at a floating price with a discount to the market. The RES producer is keener to proceed with such a structure as there is the choice to enhance output with wholesale power prices and in sufficient parallel demand to cover the offtaker. The PPA match most likely concludes with large electricity offtakers that are also “vulnerable” to power prices. Finally, in a clawback structure, which is the less popular amongst counterparties across Europe, mainly due to its complexity, the offtaker locks in a PPA price but benefits from downward market price movements, subject to limitations defined in the agreement. Upward price movements are charged to the RES producers until they have clawed back the amount gained by the offtaker (relative to the PPA price). The RES producer faces a loss cap following this, in which the price reverts to the PPA price, providing a floor (also determined relative to the PPA price) to total project revenues for the RES producer. This structure’s philosophy is based on a contractual provision whereby revenues already paid to a counterparty must be returned to the other counterparty, sometimes with a penalty [21][23][25].

Figure 4. PPA pricing structure: discount to market with floor.

Cross-border PPAs (XB PPAs) refer to bilateral contracts between an RES producer and an offtaker who are located in different countries. In principle, the scheme is the same as any other PPA structure but with the added complication of dealing with a cross-border price risk and potentially differing regulatory frameworks. The transmission of energy between countries (physical cross-border PPA) depends on acquiring interconnector physical transmission rights (PTRs) and financial transmission rights (FTRs) at auction. This offers several challenges and might not always be feasible. On the other hand, XB virtual PPAs encourage competition among all market participants. Buyers are persuaded to sign PPAs to mitigate economic risks and make environmental claims. Governments and energy markets are being urged to assist and execute these new transactions, and RES producers construct more efficient projects, regardless of the PPA market present. In a multi-buyer structure, multiple offtakers can form a group and enter a PPA with a large RES Producer. Similarly, a team of RES producers can sign a PPA as a unity. This allows for another vital form of PPAs, multi-producer PPAs, which also combine the benefits of different RES technologies (wind and solar) [22][27].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su15086638

References

- Thaher, Y.A.Y.; Jaaron, A.A.M. The impact of sustainability strategic planning and management on the organizational sustainable performance: A developing-country perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 305, 114381.

- Stanitsas, M.; Kirytopoulos, K.; Vareilles, E. Facilitating sustainability transition through serious games: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 924–936.

- Haratian, M.; Tabibi, P.; Sadeghi, M.; Vaseghi, B.; Poustdouz, A. A renewable energy solution for stand-alone power generation: A case study of KhshU Site-Iran. Renew. Energy 2018, 125, 926–935.

- Stanitsas, M.; Kirytopoulos, K. Underlying factors for successful project management to construct sustainable built assets. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2022, 12, 129–146.

- Mendicino, L.; Menniti, D.; Pinnarelli, A.; Sorrentino, N. Corporate power purchase agreement: Formulation of the related levelized cost of energy and its application to a real life case study. Appl. Energy 2019, 253, 113577.

- Jain, S. Exploring structures of power purchase agreements towards supplying 24x7 variable renewable electricity. Energy 2022, 244, 122609.

- Bruck, M.; Sandborn, P. Pricing bundled renewable energy credits using a modified LCOE for power purchase agreements. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 224–235.

- Gabrielli, P.; Aboutalebi, R.; Sansavini, G. Mitigating financial risk of corporate power purchase agreements via portfolio optimization. Energy Econ. 2022, 109, 105980.

- Słotwiński, S. The Significance of the “Power Purchase Agreement” for the Development of Local Energy Markets in the Theoretical Perspective of Polish Legal Conditions. Energies 2022, 15, 6691.

- Marron, S.T.; Tyurin, E.N.; Wile, J.H.; Trader, G. Everyone wins: Renegotiating purchase power agreements. Electr. J. 1997, 10, 76–82.

- Niu, Y.; Jiao, L.; Korneev, A. Credit development strategy of China’s banking industry to the electric power industry. Herit. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 4, 53–60.

- Gabrielli, P.; Hilsheimer, P.; Sansavini, G. Storage power purchase agreements to enable the deployment of energy storage in Europe. iScience 2022, 25, 104701.

- Duraković, B.; Mešetović, S. Thermal performances of glazed energy storage systems with various storage materials: An experimental study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 45, 422–430.

- Crespi, E.; Colbertaldo, P.; Guandalini, G.; Campanari, S. Energy storage with Power-to-Power systems relying on photovoltaic and hydrogen: Modelling the operation with secondary reserve provision. J. Energy Storag. 2022, 55, 105613.

- Setya Budi, R.F.; Hadi, S.P. Indonesia’s deregulated generation expansion planning model based on mixed strategy game theory model for determining the optimal power purchase agreement. Energy 2022, 260, 125014.

- Miller, N.W. Unshackled: Hawai’i’s Innovative New Power Purchase Agreements for Hybrid Solar Photovoltaic and Energy Storage Projects . IEEE Electrif. Mag. 2022, 10, 7–97.

- Re-Source|European Platform for Corporate Renewable Energy Sourcing. Risk Mitigation for Corporate Renewable PPAs; Re-Source: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Yoshino, N.; Rasoulinezhad, E.; Rimaud, C. Power purchase agreements with incremental tariffs in local currency: An innovative green finance tool. Glob. Financ. J. 2021, 50, 100666.

- Ghiassi-Farrokhfal, Y.; Ketter, W.; Collins, J. Making green power purchase agreements more predictable and reliable for companies. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 144, 113514.

- Harada, L.N.; Coussi, M. Power purchase agreements: An emerging tool at the centre of the European energy transition a focus on France. Eur. Energy Environ. Law Rev. 2020, 29, 195–205.

- WBCSD. Pricing Structures for Corporate Renewable PPAs; WBCSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; p. 19.

- WBCSD. Cross-Border Renewable PPAs in Europe: An Overview for Corporate Buyers; WBCSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; p. 40.

- Deloitte. Accelerate Accounting for Power Purchase Agreements; Deloitte Global: Helsinki, The Netherland, 2022.

- Akinci, E.; Ciszuk, S. Nordic PPAs—Effects on Renewable Growth and Implications for Electricity Markets. In Energy Insight 84; The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Ed.; 2021; Available online: https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Insight-84-Nordic-PPAs-effects-on-renewable-growth-and-implications-for-electricity-markets.pdfp (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Pexapark. Deconstructing Baseload PPA; Pexapark: Wiesenstrasse, Switzerland, 2021.

- Rauch, J.N. The Effect of Different Market Conditions on the Hedge Value of Long-Term Contracts for Zero-Fuel-Cost Renewable Resources. Electr. J. 2013, 26, 44–51.

- Aryal, S.; Dhakal, S. Medium-term assessment of cross border trading potential of Nepal’s renewable energy using TIMES energy system optimization platform. Energy Policy 2022, 168, 113098.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!