Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Proper bowel preparation is of paramount importance for enhancing adenoma detection rates and reducing postcolonoscopic colorectal cancer risk. The utilization of artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged for the preprocedural detection of inadequate bowel preparation, holding the potential to guide the preparation process immediately preceding colonoscopy.

- colonoscopy

- bowel preparation

- artificial intelligence

1. Introduction

A colonoscopy is the gold standard for identifying colorectal neoplastic lesions. Its use in asymptomatic individuals enables the early detection of neoplastic lesions such as colorectal adenomas and early colorectal cancer (CRC) [1]. When used as a screening tool, a colonoscopy has the potential to decrease the incidence and mortality associated with CRC [2]. Enhanced colonoscopy efficiency is sought through proposed quality criteria, encompassing adherence to established indications and the recommended postpolypectomy surveillance intervals [3].

Of paramount significance are two pivotal indicators of quality: the cecal intubation rate and the adenoma detection rate, and both are intrinsically tied to proficient colon cleansing [3]. Inadequate cleansing decreases colonoscopy efficiency due to the necessity for repeat procedures, generating increased expenses [4]. Furthermore, it engenders delays in diagnosing malignant or precancerous lesions, curtails the adenoma detection rate (ADR), and increases procedural times and possibly patient risk. This predicament garners heightened importance within the prevailing backdrop of the COVID-19 crisis, wherein, for a substantial proportion of elective procedures, some endoscopy units have reported up to a 95% deferment of the endoscopy workload owing to the state of emergency [5]. The implications of such delays on patient prognoses remain uncertain.

Given these exigencies and the evolving landscape, the need for strategies for increasing colonoscopy efficiency is significant. Achieving proper bowel cleansing is of crucial importance for increasing efficiency. Acceptable benchmarks, deemed to fall within the 10% to 15% range, have been established [4][6]. However, the prevalence of suboptimal colonoscopies across endoscopy units evinces considerable variability in studies, spanning from 6.8% to 33% [7]. A multitude of factors have been linked to inadequate bowel preparation, prompting endeavors to mitigate suboptimal bowel cleansing through interventional studies aimed at high-risk patients with poor bowel cleansing [8].

2. Strategies for Improving Bowel Cleansing

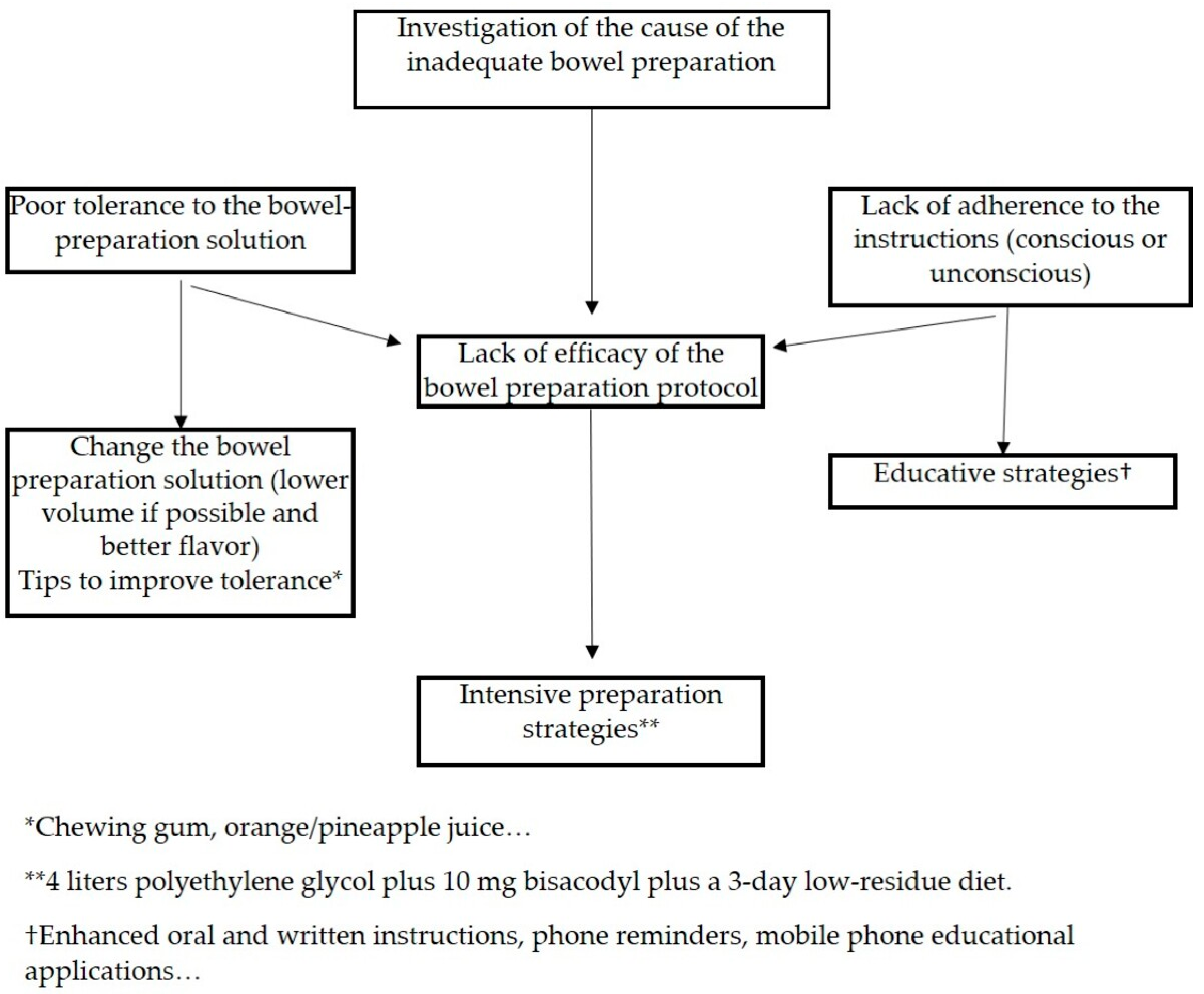

The selection of a bowel-cleansing strategy depends on the cause of a failed bowel preparation. Therefore, two groups of patients can be differentiated. First, in patients with previous colonoscopies with poor preparation, efforts should be made to determine the cause of the failed bowel preparation because the strategy to follow will be different. In the case of poor tolerance to the bowel solution or incompliance, enhanced instructions (education) and/or providing the same tips to increase tolerance should be the strategy of choice.

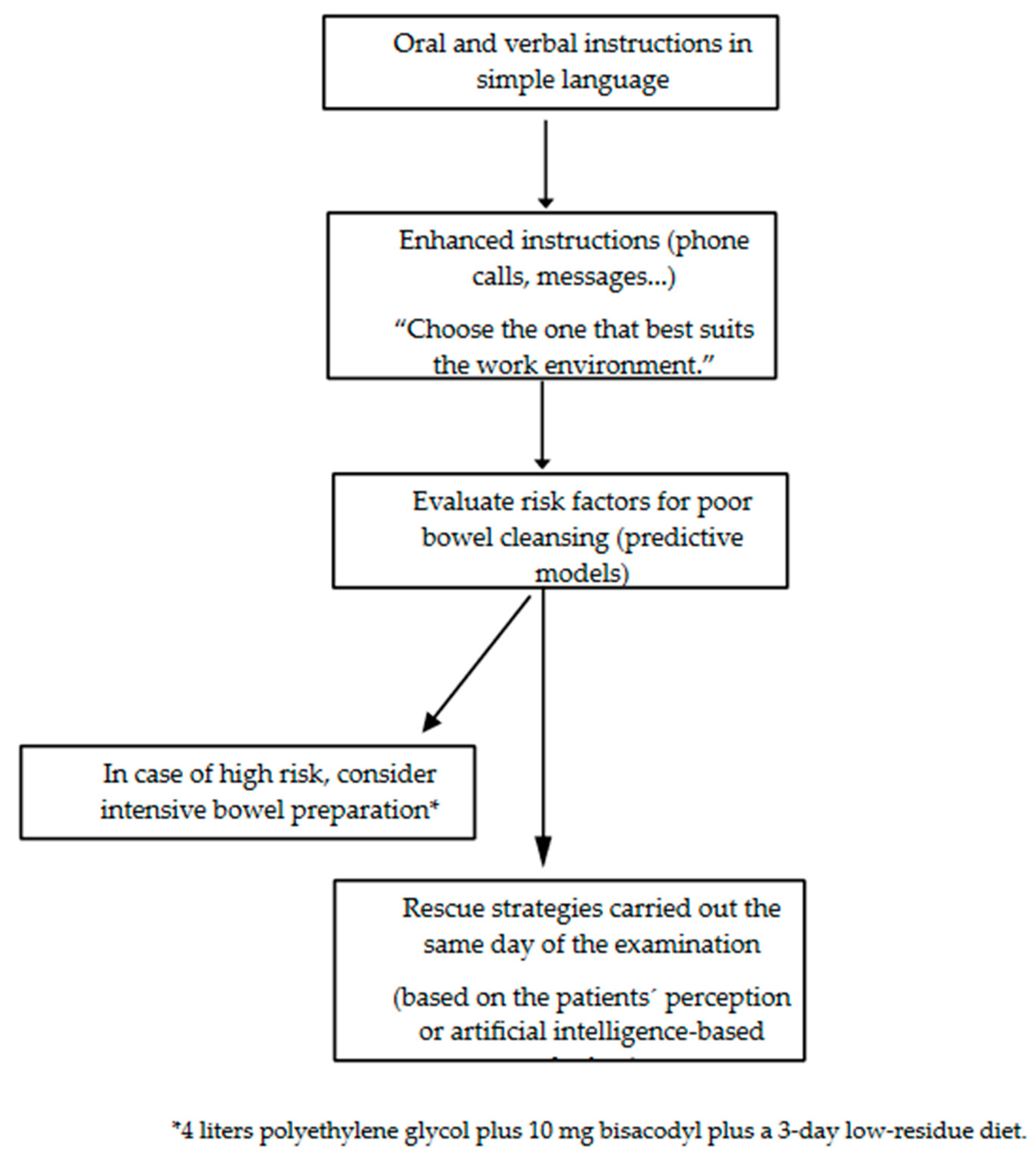

A proposal for this approach is shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1. Proposal for improving bowel cleaning in patients with previous colonoscopies with inadequate bowel preparation.

Figure 2. Tips for improving bowel cleaning in naïve patients.

Different strategies are set out in the next section.

2.1. Strategies for Increasing Tolerance

Different adjuvants have been recommended to improve palatability. Chewing gum has been proven to increase patients’ satisfaction and willingness to repeat the same bowel preparation and to reduce the time taken to drink the bowel preparation in RCTs. Chewing gum also reduces abdominal discomfort, nausea, and vomiting. Contradictory results have been found in terms of bowel cleansing [9][10]. Some beverages, either as bowel prep diluents, ingested during the pause interval of drinking the preparation, kept in the mouth before bowel preparation ingestion, or drunk after bowel cleansing, were tested [11][12][13]. In RCTs, Coca Cola used as a diluent has resulted in an improvement in the flavor, a shorter time to drink the bowel solution, increased willingness to repeat the same bowel preparation, and an increased quality of bowel cleansing during the colonoscopy [13]. Although other beverages have improved patient satisfaction and decreased side effects, they did not improve bowel cleansing [11][12]. A recent meta-analysis tested whether the use of adjuvants for improving palatability improved patient experience and increased cleansing quality. A total of six RCTs (with 1187 patients) using different adjuvants were included. Overall, the authors found that the adjuvants had significant benefits in improving the flavor and patient willingness to repeat the same bowel preparation protocol, and they decreased side effects and even improved the cleansing quality (odds ratio of 2.52, 95% confidence interval [1.31–4.85]) [14].

2.2. Strategies for Decreasing Incompliance

Incompliance has been stated as a major burden for bowel preparation. In a prospective study carried out on 462 outpatients, the probability of poor bowel preparation was more than twice as high in patients with poor adherence to the instructions. Incompliance was the most important predictor of poor bowel cleansing [15].

Several meta-analyses have been recently reported, highlighting the benefits of enhanced instructions in bowel cleansing [16][17][18][19]. The meta-analysis by Guo et al. also found a higher detection rate of polyps and adenomas in the group of patients who received the intervention. Generally, in these meta-analyses, compliance with the instructions, willingness to repeat the same preparation, and cleansing quality during the colonoscopy were higher in the groups of patients who received the educational intervention [18]. However, educational strategies encompass a heterogeneous group of interventions that may yield disparate results, leading to a lack of consensus on which intervention is the most effective. The types of educational interventions are discussed below based on the type of strategy employed:

- -

-

Individual or group informative sessions: These sessions are conducted by trained health care personnel, and in them, a patient receives instructions regarding dietary aspects, the type and administration of the evacuating solution, and precautions to be taken with the home treatment. The results are conflicting in the published studies [20][21].

- -

-

Printed educational materials: Using brochures or pamphlets that combine text with illustrative images or drawings about good or poor colon cleansing, lesions were detected based on colonic cleanliness and permitted or prohibited foods. The distribution of this material had positive effects on cleansing quality in most of the studies [22][23].

- -

-

Audiovisual material: Educational videos can enhance understanding through the use of simple words, illustrations, and video clips. Some RCTs have compared this strategy to the standard practice, with two studies observing better colon cleansing quality in the intervention groups [24].

- -

-

Phone calls or text messages: Through telephone communication, the importance of colonic preparation, the method of following the diet, and taking the evacuating solution are emphasized, along with addressing doubts and providing reminders of scheduled appointments. Such RCTs have demonstrated better colonic cleansing quality in patients assigned to intervention groups [25].

- -

-

Mobile applications and social networks: Mobile phones and social networks have become significant sources of medical information. RCTs have evaluated colon cleansing quality in patients who used smartphone applications detailing the information about the colonoscopy preparation, with explanatory images and/or videos, compared to the utility of receiving oral and written instructions [26]. Colonic cleansing quality was superior in the intervention groups in these studies [26][27].

2.3. Intensified Interventions

Several studies have compared low-volume-based preparations (1 L or 2 L of cleansing solution with or without an adjuvant) with high-volume-based preparations (3 L or 4 L of bowel preparation); however, few studies have compared intensified bowel protocols [28]. It makes sense to use this approach in patients with risk factors for poor bowel cleansing since a majority of patients will be cleansed with a standard bowel preparation. One RCT compared a high-volume-based enhanced bowel protocol (4 L of PEG plus bisacodyl) with a low-volume protocol (2 L of PEG plus ASC acid plus bisacodyl) in 256 patients who had failed standard bowel preparation [28]. The intensified high-volume protocol was superior in terms of cleansing quality in both the intention-to-treat analysis (odds ratio of 2.07, 95% confidence interval [1.16–3.69]) and in the per-protocol analysis (odds ratio of 2.55, 95% confidence interval [1.4–32.92]). Interestingly, the patients who benefited most from the high-volume protocol were those who received a standard low-volume preparation solution in their first colonoscopies. No statistically significant differences were found regarding tolerance or ADR between the groups.

In patients undergoing first-time colonoscopies, one RCT compared an enhanced bowel preparation protocol (4 L of PEG plus bisacodyl) with a standard low-volume protocol (2 L of PEG plus ASC) in 260 patients with high risks of poor bowel preparation. These patients were selected by using a predictive score [29]. In this study, an enhanced high-volume preparation protocol was not better than the standard protocol either in the intention-to-treat analysis (ITT) or in the per-protocol analysis (PP). The authors hypothesized that the low sample size could have hindered the results of the study since in a majority of the patients, administering a conventional colon preparation would have been sufficient.

Therefore, the implementation of enhanced bowel preparations remains controversial.

2.4. Rescue Strategies

Same-day or next-day colonoscopies after additional bowel preparation have been suggested in the current guidelines, although with a low level of evidence and a low grade of recommendation [4]. There are some experiences using this type of strategy. Yang et al. randomized 131 patients with poor bowel preparation (BBPS of < 2 in at least one segment) to a 1 L PEG enema administered through the colonoscopy channel in the right colon or 2 L of oral PEG plus ascorbic acid during same day of the examination [30]. The additional oral solution managed to rescue up to 81% of the patients compared to 50% with the enema administration (p < 0.001). Different devices based on endoscopic irrigation pumps have been developed [31][32][33]. These devices utilize pressurized water, saline solutions, or even CO2 combined with a suction system, and these are introduced through the working channel of the endoscope or in parallel to it, or they are used prior to the procedure. In general, and in the absence of randomized studies with larger sample sizes, these devices appear to enhance the quality of colon cleansing.

3. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Improving Bowel Cleansing

At present, a notable advancement is unfolding in the realm of artificial intelligence (AI) applications within the medical field, specifically in gastroenterology and especially in gastrointestinal endoscopy [34]. Concerning bowel preparations, a majority of the research efforts have focused on training and verifying convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to identify bowel cleanliness levels during colonoscopies utilizing well-established cleansing scales [35]. These systems hold promise in overcoming the difficulties arising from discrepancies in assessments between various observers while evaluating colon cleanliness during colonoscopy procedures. Within this array of systems, ENDOANGEL has emerged as the only commercially accessible real-time solution for assessing colon cleanliness [36]. Although these systems are useful for more objectively assessing bowel cleansing during a colonoscopy, they do not help to prevent poor bowel preparation.

Recently, two RCTs carried out on Chinese populations utilized AI platforms using a CNN to guide bowel preparation. In both of these studies, the CNNs were trained with annotated images of rectal effluents [37][38].

In the first study, the CNN was trained using 4302 images, and it demonstrated excellent accuracy in predicting bowel cleansing (>95%) [37]. A total of 1454 patients were enrolled and randomized into either an intervention group or a control group. The patients in the intervention group were required to scan a quick response code (QR code) and upload an image of their rectal effluent during the bowel preparation process. The uploaded image was then analyzed by the CNN, providing an assessment of “pass” or “not pass”. For cases where the assessment was “not pass,” the system provided general instructions for enhancing the bowel preparations. The quality of bowel preparation, as assessed by the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS), did not differ significantly between the groups (AI group: 90.7% vs. control group: 91.5%; p = 0.429). Upon comparing the CNN predictions with the BBPS, it became evident that the CNN model faced challenges in effectively discerning cleansing quality. Among the patients with BBPS scores of <6 points, only 6 out of 71 (8.45%) were correctly classified by the CNN, and the remaining images were erroneously classified as having sufficient preparation. Conversely, 26 patients with BBPS scores of ≥6 points were mistakenly categorized as having inadequate preparation. Consequently, the clinical utility of this CNN model could be limited when guiding intervention strategies for patients predicted to have poor cleansing quality on the same day. In the second study, a ShuffleNet v2 CNN was trained using 5362 images of rectal effluents, and it achieved an accuracy of 95.15% in predicting bowel cleansing quality [38]. Subsequently, a total of 524 patients were randomized to either a CNN-powered smartphone application or a control group. In this case, the intervention group demonstrated superior colonic cleansing quality compared to the control group, as evidenced by both the ITT analysis (88.54% vs. 65.59%, respectively; p < 0.001) and the PP analysis (89.78% vs. 65.59%, respectively; p < 0.001). Nevertheless, the rate of acceptable colon cleansing in the control group was significantly lower than anticipated (88.54% in the AI group vs. 65.59% in the control group).

These studies present promising results for guiding colon bowel cleansing on the same day as an examination. However, further research is warranted, especially in Western countries where the populations are aging and possess less familiarity with new technologies.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/medicina59101834

References

- Atkin, W.; Wooldrage, K.; Parkin, D.M.; Wooldrage, K.; Parkin, D.M.; Kralj-Hans, I.; MacRae, E.; Shah, U.; Duffy, S.; Cross, A.J.; et al. Long term effects of once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening after 17 years of follow-up: The UK Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Screening randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 1299–1311.

- Brenner, H.; Stock, C.; Hoffmeister, M. Effect, of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ 2014, 348, g2467.

- Kaminski, M.F.; Thomas-Gibson, S.; Bugajski, M.; Bretthauer, M.; Rees, C.J.; Dekker, E.; Hoff, G.; Jover, R.; Suchanek, S.; Ferlitsch, M.; et al. Performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: A European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Quality Improvement Initiative. Endoscopy 2017, 49, 378–397.

- Hassan, C.; East, J.; Radaelli, F.; Spada, C.; Benamouzig, R.; Bisschops, R.; Bretthauer, M.; Dekker, E.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; Ferlitsch, M.; et al. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline—Update 2019. Endoscopy 2019, 51, 775–794.

- Rutter, M.D.; Brookes, M.; Lee, T.J.; Rogers, P.; Sharp, L. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK endoscopic activity and cancer detection: A National Endoscopy Database Analysis. Gut 2021, 70, 537–543.

- Johnson, D.A.; Barkun, A.N.; Cohen, L.B.; Dominitz, J.A.; Kaltenbach, T.; Martel, M.; Robertson, D.J.; Boland, C.R.; Giardello, F.M.; Lieberman, D.A.; et al. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: Recommendations from the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 903–924.

- Alvarez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Flores, L.; Roux, J.A.; Seoane, A.; Pedro-Botet, J.; Carot, L.; Fernandez-Clotet, A.; Raga, A.; Pantaleon, M.A.; Barranco, L.; et al. Efficacy of a multifactorial strategy for bowel preparation in diabetic patients undergoing colonoscopy: A randomized trial. Endoscopy 2016, 48, 1003–1009.

- Ness, R.M.; Manam, R.; Hoen, H.; Chalasani, N. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 96, 1797–1802.

- Fang, J.; Wang, S.L.; Fu, H.Y.; Li, Z.S.; Bai, Y. Impact of gum chewing on the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy: An endoscopist-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017, 86, 187–191.

- Lee, J.; Lee, E.; Kim, Y.; Kim, E.; Lee, Y. Effects of gum chewing on abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting and intake adherence to polyethylene glycol solution of patients in colonoscopy preparation. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 518–525.

- Choi, H.S.; Shim, C.S.; Kim, G.W.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Sung, I.K.; Park, H.S.; Kim, J.H. Orange juice intake reduces patient discomfort and is effective for bowel cleansing with polyethylene glycol during bowel preparation. Dis. Colon. Rectum 2014, 57, 1220–1227.

- Hao, Z.; Gong, L.; Shen, Q.; Wang, H.; Feng, S.; Wang, X.; Cai, Y.; Chen, J. Effectiveness of concomitant use of green tea and polyethylene glycol in bowel preparation for colonoscopy: A randomized controlled study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 150.

- Seow-En, I.; Seow-Choen, F. A prospective randomized trial on the use of Coca-Cola Zero((R)) vs water for polyethylene glycol bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Colorectal Dis. 2016, 18, 717–723.

- Kamran, U.; Abbasi, A.; Tahir, I.; Hodson, J.; Siau, K. Can adjuncts to bowel preparation for colonoscopy improve patient experience and result in superior bowel cleanliness? A systematic review and meta-analysis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2020, 8, 1217–1227.

- Menees, S.B.; Elliott, E.; Govani, S.; Anastassiades, C.; Judd, S.; Urganus, A.; Boyce, S.; Schoenfeld, P. The impact of bowel cleansing on follow-up recommendations in average-risk patients with a normal colonoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 148–154.

- Chang, C.W.; Shih, S.C.; Wang, H.Y.; Chu, C.H.; Wang, T.E.; Hung, C.Y.; Shieh, T.Y.; Lin, Y.S.; Chen, M.J. Meta-analysis: The effect of patient education on bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Endosc. Int. Open 2015, 3, E646–E652.

- Guo, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhai, J.; Liu, Q.; Ding, K.; Pan, Y. Reinforced education improves the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231888.

- Guo, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Leung, F.; Luo, H.; Kang, X.; Li, X.; Jia, H.; Yang, S.; Tao, Q.; et al. Enhanced instructions improve the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017, 85, 90–97.e96.

- Peng, S.; Liu, S.; Lei, J.; Ren, W.; Xiao, L.; Liu, X.; Lu, M.; Zhou, K. Supplementary education can improve the rate of adequate bowel preparation in outpatients: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266780.

- Elvas, L.; Brito, D.; Areia, M.; Carvalho, R.; Alves, S.; Saraiva, S.; Cadime, A.T. Impact of Personalised Patient Education on Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy: Prospective Randomised Controlled Trial. GE Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 24, 22–30.

- Modi, C.; Depasquale, J.R.; Digiacomo, W.S.; Malinowski, J.E.; Engelhardt, K.; Shaikh, S.N.; Kothari, S.T.; Kottam, R.; Shakov, R.; Maksoud, C.; et al. Impact of patient education on quality of bowel preparation in outpatient colonoscopies. Qual. Prim. Care 2009, 17, 397–404.

- Calderwood, A.H.; Lai, E.J.; Fix, O.K.; Jacobson, B.C. An endoscopist-blinded, randomized, controlled trial of a simple visual aid to improve bowel preparation for screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011, 73, 307–314.

- Spiegel, B.M.; Talley, J.; Shekelle, P.; Agarwal, N.; Snyder, B.; Bolus, R.; Kurzbard, N.; Chan, M.; Ho, A.; Kaneshiro, M.; et al. Development and validation of a novel patient educational booklet to enhance colonoscopy preparation. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 875–883.

- Park, J.S.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.I.; Shin, C.H.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, W.S.; Moon, S. A randomized controlled trial of an educational video to improve quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016, 16, 64.

- Liu, X.; Luo, H.; Zhang, L.; Leung, F.W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, R.; Hui, N.; Wu, K.; Fan, D.; et al. Telephone-based re-education on the day before colonoscopy improves the quality of bowel preparation and the polyp detection rate: A prospective colonoscopist-blinded randomised controlled study. Gut 2014, 63, 125–130.

- Back, S.Y.; Kim, H.G.; Ahn, E.M.; Park, S.; Jeon, S.R.; Im, H.H.; Kim, J.O.; Ko, B.M.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, T.H.; et al. Impact of patient audiovisual re-education via a smartphone on the quality of bowel preparation before colonoscopy: A single-blinded randomized study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 87, 789–799.e784.

- Kang, X.; Zhao, L.; Leung, F.; Luo, H.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Guo, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Hui, N.; et al. Delivery of Instructions via Mobile Social Media App Increases Quality of Bowel Preparation. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 429–435.e423.

- Gimeno-Garcia, A.Z.; Hernandez, G.; Aldea, A.; Nicolas-Perez, D.; Jimenez, A.; Carrillo, M.; Felipe, V.; Alarcon-Fernandez, O.; Hernandez-Guerra, M.; Romero, R.; et al. Comparison of Two Intensive Bowel Cleansing Regimens in Patients with Previous Poor Bowel Preparation: A Randomized Controlled Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 951–958.

- Gimeno-Garcia, A.Z.; de la Barreda, H.R.; Reygosa, C.; Hernandez, A.; Mascareno, I.; Nicolas-Perez, D.; Jimenez, A.; Lara, A.J.; Alarcon-Fernandez, O.; Hernandez-Guerra, M.; et al. Impact of a 1-day versus 3-day low-residue diet on bowel cleansing quality before colonoscopy: A randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy 2019, 51, 628–636.

- Yang, H.J.; Park, D.I.; Park, S.K.; Kim, S.; Lee, T.; Jung, Y.; Eun, C.S.; Han, D.S. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Colonoscopic Enema with Additional Oral Preparation as a Salvage for Inadequate Bowel Cleansing Before Colonoscopy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2019, 53, e308–e315.

- Cadoni, S.; Falt, P.; Rondonotti, E.; Radaelli, F.; Fojtik, P.; Gallittu, P.; Liggi, M.; Amato, A.; Paggi, S.; Smajstrla, V.; et al. Water exchange for screening colonoscopy increases adenoma detection rate: A multicenter double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy 2017, 49, 456–467.

- Moshkowitz, M.; Fokra, A.; Itzhak, Y.; Arber, N.; Santo, E. Feasibility study of minimal prepared hydroflush screening colonoscopy. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2016, 4, 105–109.

- van Keulen, K.E.; Neumann, H.; Schattenberg, J.M.; van Esch, A.A.J.; Kievit, W.; Spaander, M.C.W.; Siersema, P.D. A novel device for intracolonoscopy cleansing of inadequately prepared colonoscopy patients: A feasibility study. Endoscopy 2019, 51, 85–92.

- Berzin, T.M.; Parasa, S.; Wallace, M.B.; Gross, S.A.; Repici, A.; Sharma, P. Position statement on priorities for artificial intelligence in GI endoscopy: A report by the ASGE Task Force. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 92, 951–959.

- Lee, J.Y.; Calderwood, A.H.; Karnes, W.; Requa, J.; Jacobson, B.C.; Wallace, M.B. Artificial intelligence for the assessment of bowel preparation. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2022, 95, 512–518e511.

- Zhou, J.; Wu, L.; Wan, X.; Shen, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, S.; Kang, J.; et al. A novel artificial intelligence system for the assessment of bowel preparation (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, 428–435.e422.

- Lu, Y.B.; Lu, S.C.; Huang, Y.N.; Cai, S.T.; Le, P.H.; Hsu, F.Y.; Hu, Y.X.; Hsieh, H.S.; Chen, W.T.; Xia, G.L.; et al. A Novel Convolutional Neural Network Model as an Alternative Approach to Bowel Preparation Evaluation Before Colonoscopy in the COVID-19 Era: A Multicenter, Single-Blinded, Randomized Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 1437–1443.

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, D.F.; Wu, H.L.; Fu, P.Y.; Feng, L.; Zhuang, K.; Geng, Z.H.; Li, K.K.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhu, B.Q.; et al. Improving, bowel preparation for colonoscopy with a smartphone application driven by artificial intelligence. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 41.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!