Histological subtypes of retroperitoneal epithelial carcinomas include mucinous [

]. Morphologically, mucinous, serous, and endometrioid tumors resemble the phenotype of the colon, fallopian tube, and endometrium, respectively [

]. Clear cell carcinoma develops in the female genital tract (the ovary, endometrium, cervix, and vagina) as well as in the kidney, and may have similar morphological features regardless of the site of origin [

].

Retroperitoneal carcinomas develop in the lymph nodes and/or extranodal sites. In cases of huge tumors, this classification may not be possible. When carcinomas are found in the lymph nodes alone, they may be diagnosed as carcinoma of unknown primary [

33].

3. Previously Postulated Pathogenesis of Retroperitoneal Carcinomas

Although the pathogenesis of primary retroperitoneal carcinomas has not been elucidated, several hypotheses have been postulated [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. The most widely accepted theory is metaplasia of coelomic epithelium [

14,

15,

16,

46,

47,

48]. Other possible origins include extra-ovarian endometriosis, teratoma or primordial germ cell, ectopic ovarian tissue, and intestinal duplication (enterogenic cyst) [

17,

21].

The coelomic epithelium gives rise to the peritoneum [

50], and invagination of the peritoneum results in inclusion cysts in a retroperitoneal space [

45]. The Müllerian duct, which eventually forms the fallopian tube, endometrium, endocervix, and the upper third of the vagina, is known to form by invagination of the coelomic epithelium [

51]. The coelomic epithelium covering cysts may subsequently undergo metaplasia [

52]. Malignant transformation of endometriosis, which is a gynecological disease defined by the histological presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity [

53], is a rare but well-known complication. Migratory arrest of primordial germ cells is thought to be the basis of a teratoma in the retroperitoneal space. Monodermal variants of teratomas may be an origin of retroperitoneal carcinomas [

47,

48]. Ectopic ovarian tissue and intestinal duplication may be the origins of retroperitoneal carcinomas [

47,

48]. However, the intestinal duplication hypothesis seems unlikely, as enterogenic cysts are gut-like and they consist of one or two layers of smooth muscle and gut mucosa [

54].

4. Pathogenesis of Ovarian Carcinomas

Traditionally, all of the four major subtypes of ovarian carcinomas, i.e., serous, endometrioid, clear cell, and mucinous tumors, were thought to derive from the common origin, i.e., ovarian surface epithelium [56,57]. The ovarian surface epithelium, which is derived from the coelomic epithelium, is the pelvic peritoneum that overlies the ovary and lines ovarian epithelial inclusion cysts [58,59]. In contrast to this traditional view, most ovarian carcinomas are now believed to derive from endometrial tissue, fallopian tube tissue, and germ cells [60]. Thus, most ovarian carcinomas are primarily imported from either endometrial or fallopian tube epithelium, unlike other human cancers in which all primary tumors arise de novo [61].

4.1. Mucinous Carcinoma

Among the four major subtypes of ovarian carcinomas, mucinous carcinoma is distinct from other histologic subtypes [

62]. Different from non-mucinous carcinomas that morphologically resemble epithelia originating in the Müllerian duct, mucinous carcinoma resembles the colon epithelium. Risk/protective factors for ovarian carcinomas include parity, breast-feeding, oral contraceptive use, and family history of ovarian/breast cancer [

63]. However, these factors were not associated with the development of mucinous carcinomas [

64,

65,

66].

Mucinous ovarian carcinoma develops via a sequence from benign tumor through borderline tumor to invasive cancer [

67,

68]. In contrast to non-mucinous ovarian carcinomas that are associated with ovulation and menstruation [

69,

70,

71], a mucinous ovarian carcinoma develops in premenarchal girls [

72], suggesting that some mucinous tumors have common features with germ cell tumors. Smoking [

64,

65,

66] and heavy alcohol consumption [

73] that is associated with colorectal cancers [

74] are risk factors for mucinous carcinomas.

Recently, mucinous carcinomas are suggested to originate from either teratomas or Brenner tumors [

75]. Mucinous cystic tumors sometimes arise in the context of mature cystic teratomas and other primordial germ cell tumors [

76,

77,

78]. Patients with teratoma-associated mucinous tumors were significantly younger than patients with Brenner tumor-associated mucinous tumors (43 vs. 61 years) [

75].

4.2. Serous Carcinoma

Most serous carcinomas develop from the fallopian tube epithelium [

4,

5]. Serous carcinomas, the most common histological subtype of epithelial ovarian carcinoma, are divided into high-grade and low-grade carcinomas, as they are different in terms of pathogenesis, disease spread pattern, and prognosis [

5]. A significant proportion of high-grade serous carcinoma develops in the secretory epithelial cells of the tubal fimbria [

83,

84]. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy has been performed in women with germline

BRCA mutation who are at risk for developing high-grade serous carcinoma, since high-grade serous carcinoma cannot be detected early by screening using transvaginal ultrasound [

85,

86]. Pathological evaluation of the removed ovaries and fallopian tubes revealed that a precursor lesion of high-grade serous carcinoma, serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, is located in the fallopian tube epithelium [

87]. This discovery led to a paradigm shift in our understanding of the origin of ovarian carcinomas. However, 12–40% of high-grade serous carcinomas are reported to derive from ovarian surface epithelium [

4,

88,

89].

4.3. Endometrioid Carcinoma

Endometrioid carcinoma, as well as clear cell carcinoma, is derived from endometriosis. Endometriosis, in particular endometriotic cyst, is a precursor to endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas [

93,

94,

95], as the molecular genetic alterations present in endometriosis-associated carcinomas can be found in adjacent endometriosis lesions [

95]. Ovarian endometriosis occurs primarily as a result of retrograde menstruation and implantation of endometrial tissue fragments in ovarian inclusion cyst [

70,

96].

4.4. Clear Cell Carcinoma

Although clear cell carcinoma is another endometriosis-associated carcinoma in women, it develops not only in ovarian endometriotic cysts but also the kidney [

99,

100,

101]. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary shares many histologic features with renal cell carcinoma, especially translocation-associated renal cell carcinoma, hence the determination of the origin may not be possible based on the morphology alone [

101]. Using immunohistochemical markers, ovarian clear cell carcinoma can be distinguished from renal clear cell and translocation-associated carcinoma [

101].

4.5. Carcinosarcoma

Carcinosarcomas are biphasic neoplasms that are composed of an admixture of malignant epithelial and mesenchymal elements. Most of the gynecological (uterine and ovarian) carcinosarcomas have a monoclonal origin [

103], as the mutations identified were present in both carcinomatous and sarcomatous components [

104]. Carcinomatous cells transform into sarcomatous cells [

105,

106,

107]. Heterogeneous molecular features observed in uterine carcinosarcomas resemble those observed in endometrial carcinomas, with some showing endometrioid carcinoma-like and others showing serous carcinoma-like mutation profiles [

104]. Frequent mutations observed in uterine carcinosarcomas are similar to endometrioid and serous uterine carcinomas [

108]. Thus, carcinosarcoma may derive from endometrioid or serous carcinoma.

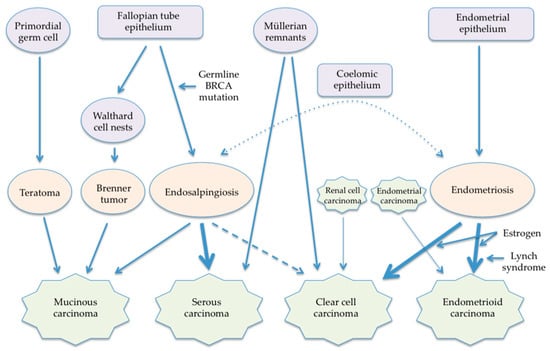

5. Newly Proposed Hypothesis on Pathogenesis of Retroperitoneal Carcinomas

Like the pathogenesis of ovarian carcinomas, the pathogenesis of retroperitoneal carcinomas may differ by histologic subtype, considering their similarity in morphology and gender preference. A major shortcoming of the previously proposed hypotheses is that they consider all histologic subtypes to have a common pathogenesis. Although the theory of coelomic metaplasia cannot be excluded, new theories of the pathogenesis of retroperitoneal carcinomas reflecting the new paradigm of ovarian carcinogenesis can be postulated (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Newly proposed pathogenesis of retroperitoneal carcinomas.

5.1. Mucinous Carcinoma

Origins of retroperitoneal mucinous tumors may be primordial germ cells and Walthard cell nests like ovarian mucinous tumors. Primary retroperitoneal mucinous carcinomas have immunohistochemical staining patterns similar to those of ovarian mucinous tumors [

109], and mucinous tumors develop in both women and men, as well as teratoma that is of germ cell origin. The migration of primordial germ cells in the embryo starts from the dorsal wall of the yolk sac. Then primordial germ cells migrate into the midgut and hindgut, passing through the dorsal mesentery into the gonadal ridges. Thus, mucinous tumors can arise from primordial germ cells that stopped anywhere in the retroperitoneal space. Mucinous carcinomas arising from a retroperitoneal mature cystic teratoma have been reported [

110,

111].

5.2. Serous Carcinoma

The pathogenesis of retroperitoneal serous carcinomas appears to be associated with endosalpingiosis. Although endosalpingiosis and endometriosis occur concurrently in 34% of endosalpingiosis cases [

117], endosalpingiosis is not a variant of endometriosis as they have different clinical presentations [

117]. Endosalpingiosis is not significantly associated with infertility or chronic pain and its incidence increases with age [

118], with 40% of endosalpingiosis cases being postmenopausal [

117].

Endosalpingiosis, as well as retroperitoneal serous carcinomas, can be divided into non-nodal and nodal lesions. Non-nodal endosalpingiosis is observed in the peritoneum and subperitoneal tissues [

117]. In the peritoneal cavity, endosalpingiosis is observed in the ovary, fallopian tube, uterus, omentum, small bowel, and sigmoid colon [

117]. Its prevalence is 7.6% in women undergoing laparoscopic surgery for gynecologic conditions [

119].

The pathogenic mechanism of endosalpingiosis remains unclear. Two major theories are postulated, namely, the tubal escape theory and the Müllerian metaplasia theory [

92,

123]. In the tubal escape theory, shed tubal epithelium either implants on the peritoneal surface or disseminates via lymphatics into a lymph node [

123]. Tubal epithelia are easily sloughed off by tubal inflammation, tubal lavage, or salpingectomy [

122]. In the Müllerian metaplasia theory, latent cells present in ectopic locations outside the Müllerian tract (fallopian tube, endometrium, endocervix) retain the capacity for forming benign tubal-type glands [

92]. Endosalpingiosis that arises from the embryological remnant of the Müllerian duct may be an origin of retroperitoneal serous carcinoma, especially in men [

123].

Endosalpingiosis appears to be a latent precursor to low-grade pelvic serous carcinomas [

124] and prone to neoplastic transformation, as it represents cancer driver mutations that are observed in ovarian low-grade serous tumor [

125]. Endosalpingiosis is associated with ovarian and uterine cancers [

80].

Although low-grade serous tumor and high-grade serous carcinoma are two distinct diseases, low-grade serous carcinoma may transform into high-grade serous carcinoma in rare cases [

129,

130,

131]. A morphologic continuum between the low-grade tumors and high-grade carcinoma was observed in four cases [

129]. The same mutation of

KRAS was found in both the serous borderline tumor and the high-grade serous carcinoma components of the tumor in two cases [

129].

Serous carcinoma and endosalpingiosis can develop in men [

25,

123]. These lesions may originate from Müllerian cell rests remaining after regression of the Müllerian duct. During fetal development, before the secretion of anti-Müllerian hormone by the fetal testes, the Müllerian ducts develop in male fetuses [

133]. Thus, Müllerian tissue may remain in a male body. Endometriosis can also develop in men who had been treated with prolonged estrogen therapy for prostate cancer or diagnosed as cirrhosis [

134,

135].

5.3. Endometrioid Carcinoma

Retroperitoneal endometrioid carcinoma appears to arise from endometriosis of the urinary tract and lymph nodes. Endometrioid tumors are the majority of extragonadal endometriosis-associated carcinomas [

138]. Tumors arising in endometriosis are predominantly low-grade and confined to the site of origin [

138]. Pelvic surgery may affect the development of retroperitoneal endometrioid carcinoma.

Endometrioid carcinoma may also arise in the lymph nodes and it appears to develop from nodal endometriosis. Endometriosis is believed to disseminate via the lymphatic system [

141]. Metastatic endometriosis lesions in pelvic sentinel lymph nodes were present in women with ovarian and/or pelvic endometriosis [

142]. Interestingly, both of the patients who developed endometrioid carcinoma in the pelvic lymph nodes had Lynch syndrome [

33,

34]. Lynch syndrome is an autosomal dominant cancer predisposition syndrome caused by germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes, i.e.,

MLH1,

MSH2,

MSH6, and

PMS2, related to an increased risk of developing colorectal, endometrial, and ovarian cancers [

143]. Thus, the malignant transformation of endometriosis in the lymph nodes in women with Lynch syndrome may be likely to occur.

5.4. Clear Cell Carcinoma

Clear cell carcinoma is another endometriosis-associated carcinoma and may arise in both retroperitoneal endometriosis and lymph nodes. A case who underwent supracervical hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and received 4 years of estrogen therapy developed clear cell carcinoma arising in retroperitoneal endometriosis [

35]. This case may also suggest that estrogen replacement may be a risk factor for developing endometriosis-associated cancer [

139].

5.5. Carcinosarcoma

Retroperitoneal carcinosarcoma, as well as uterine carcinosarcoma [

108], may derive from serous or endometrioid carcinoma. In ovarian carcinosarcoma, frequently encountered epithelial components are serous, endometrioid, or undifferentiated carcinomas [

155]. Of the three retroperitoneal carcinosarcomas, one was associated with endometriosis that is known to be associated with the development of endometrioid carcinoma [

41].

6. Retroperitoneal Carcinoma as a Part of Carcinoma of Unknown Primary

Part of carcinomas of unknown primary may be a primary retroperitoneal carcinoma. Carcinoma of unknown primary represents a heterogeneous group of metastatic tumors for which a standard diagnostic work-up fails to identify the site of origin at the time of diagnosis [

157]. Patients with carcinoma of unknown primary are categorized into two prognostic subgroups according to their clinicopathologic characteristics. The majority of patients with carcinoma of unknown primary (80–85%) belong to unfavorable subsets. In this subset, two prognostic groups are identified according to LDH level and the performance status [

158,

159]. The favorable risk cancer subgroup (15–20%) includes patients with neuroendocrine carcinomas of unknown primary.

Carcinoma in the lymph node diagnosed as a carcinoma of unknown primary may be a primary carcinoma that derives from endosalpingiosis or endometriosis in the node. Serous carcinomas in the inguinal node have been reported [

161,

162]. In addition, atypical hyperplasia with noninvasive, well-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma and high-grade serous carcinoma within a focus of endometriosis in an inguinal mass in a young woman has been reported [

163]. In addition, cases with a primary tumor regressing spontaneously and lymph node metastasis remaining may be diagnosed as a carcinoma of unknown primary.

7. Conclusions

Although many hypotheses are proposed, the exact pathogenesis of retroperitoneal carcinomas remains to be elucidated. Retroperitoneal carcinomas may not originate in the coelomic epithelium but in the Müllerian epithelium, as well as ovarian carcinomas [

176]. The secondary Müllerian system, which refers to the presence of Müllerian epithelium outside the indigenous locations, has been proposed [

177] and this system may be an origin of ovarian carcinomas [

178], endometriosis [

179], endosalpingiosis [

180], and retroperitoneal carcinomas [

9,

31,

45,

54]. However, this notion remains unverified [

176]. Coelomic metaplasia may have been considered the most plausible hypothesis of retroperitoneal carcinogenesis, but direct evidence may not exist to support this theory at present. However, as ovarian serous carcinomas originate from both fallopian tube epithelium and ovarian surface epithelium [

84,

88,

89], there is a possibility that retroperitoneal carcinomas develop directly from the abdominal and pelvic peritoneum that invaginates into the retroperitoneal space.

Endosalpingiosis and endometriosis are both involved in the development of ovarian, peritoneal, and retroperitoneal carcinomas [

81,

95,

124,

125,

181,

182]. Nevertheless, the pathogenesis of these diseases, in particular endosalpingiosis, is poorly understood. Although endosalpingiosis resembles tubal epithelium, it is associated with the development of not only serous tumors, but also mucinous carcinomas [

81]. Endosalpingiosis may be a hereditary disease, similar to endometriosis [

183], as endosalpingiosis is associated with

BRCA mutation [

124]. In addition, patients with endosalpingiosis had lower overall survival than patients with endometriosis [

81]. Are shed epithelial cells of the fallopian tube a cause of endosalpingiosis and/or a precursor of both peritoneal and retroperitoneal carcinomas? If so, what is the difference between cells that become a peritoneal carcinoma and those that become a retroperitoneal carcinoma? Further studies on the pathogenesis of retroperitoneal, peritoneal, and ovarian carcinomas are necessary, as well as on endosalpingiosis and endometriosis.