Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

The interactive capabilities of social media (SM) can provide a conceptual parallel to the conversational nature underlying the concept of engagement. For example, SM users’ interactions with specific brands are concrete manifestations of engagement marked by varying degrees of affective and/or cognitive and/or behavioral investment.

- influencer

- follower

- engagement

1. Introduction

The conceptual foundations of consumer engagement build on relationship marketing theory [1]. For a company, a relationship orientation typically creates a competitive advantage, which in turn exerts a positive impact on its performance [2]. However, in addition to myriad types of engagement described in the marketing literature (e.g., brand engagement in self-concept [3], customer brand engagement [4] or consumer brand engagement [5]), definitions of engagement also abound. Hollebeek (2011) [6] construes engagement as the consumer’s level of motivation relative to the brand and their context-dependent state of mind, characterized by specific levels of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral activities. Brodie et al. (2011) [1] define engagement as a psychological state induced by consumer’s interactivity and co-creative experiences with the object. Although some definitions have aspects in common, scientific support on the nature of the concept of engagement in marketing is scant [7][8]. There is also a lack of consensus on the dimensionality of engagement [3][6]. Views diverge over the combination and number of dimensions and sub-dimensions involved in the process [9].

2. Dimensionality and Measurement of Engagement

Some researchers view engagement in a one-dimensional way [10][11][12] (e.g., clicking on online content). Other scholars argue that brand engagement should be viewed instead as a manifestation of engagement rather than an operational definition of this concept [13]. However, studies show that to offer an exceptional engagement experience, multiple dimensions must be stimulated simultaneously [14][15]. The marketing literature demonstrates that engagement is commonly measured along three dimensions, cognitive, affective/emotional, and behavioral/activation (e.g., Lourenço et al., 2022 [16]; Hollebeek et al., 2014 [17]).

3. Cognitive

The cognitive dimension consists of information processing, i.e., the perception of a brand’s usefulness and relevance. It is measured by various sub-dimensions such as influence (experience), which refers to a brand’s impact (positive or negative) in a consumer’s life [18][19]. Absorption is another sub-dimension mobilized in studies of cognitive engagement [20][21]. According to the flow theory [22], the disposition of deep absorption in an intrinsically pleasurable activity leads to strong engagement. Another dimension related to the cognitive aspect is attention [6][23]. This is the degree of concentration relative to a brand. The higher it is, the more the consumer is engaged with the subject. Then, self-congruity [24] is used to measure the identity aspect of cognitive engagement. The consumer integrates the identity signal of a brand into his self-concept [25] which allows him to define himself by projecting a certain image to those around him [3]. In addition, self-congruence [24] is used to measure the identity aspect of cognitive engagement. The last sub-dimension is identification, which is when the consumer’s self-image overlaps with that of the brand [26][27], whether real, social, ideal, or social-ideal [24].

4. Affective

The affective dimension is based on emotional congruence with the brand characterized by enthusiasm [21][28] and pleasure [29]. The affective aspect also includes attachment. Derived from experiences, emotions, and expectations associated with a brand [30], attachment motivates individuals to engage in and adopt specific behaviors [31]. In addition, studies in psychology have found a positive correlation between engagement and personal well-being (e.g., [32][33]). The more engaged the individual is, the higher their life satisfaction [9].

5. Behavioral

The behavioral dimension represents the consumer’s activation towards the brand [17]. Various actions can be considered manifestations of engagement, for example word-of-mouth [34], compulsive buying [35], as well as participation and interaction/co-creation [28]. Indeed, past studies have underscored the importance of interactivity in the consumer-brand dyad, as it enables voluntary effort to maintain a level of interaction that elicits continued engagement (e.g., [1][7]). Obviously, through SM, the consumer is able to interact directly with the brand [36], faster than in an offline context [37][38]. By the same token, the conceptualization and operationalization of behavioral engagement underwent a major transformation during the 2000s.

SM have transformed the nature and practice of online communication into an extensive two-way dialogue between users [39] and brands. Digital technologies facilitate users’ social participation [40] and progressively build intimacy [41], thus engendering novel behaviors that establish new social norms [42][43]. However, consensus about what constitutes behavioral engagement on SM is lacking [44]. Some authors measure engagement by the number of brand followers [45], while others link it to specific actions (e.g., the number of “likes” of a post) [46]. On the other hand, obtaining “likes” is a low engagement action and brands want more engaged and active exchanges with their followers (e.g., a comment, a share) [47]. It is therefore essential to differentiate the levels of behavioral engagement in the digital context.

The Consumers’ online brand-related activities (COBRA) behavioral construct [46][48] provides a unifying framework for analyzing consumers’ activities related to a brand’s content on SM [49]. COBRA activities are classified under three dimensions corresponding to a path of gradual involvement [46]. The first level is consuming, which entails followers’ passive participation in online brand communities [50]. One such example is reading. The second level is contributing; it includes interaction with brand-related content [51], and is exemplified by sharing. The third level is creating, which includes publishing original brand-related content [52], e.g., create a story (The stories are an option of the application on IG which allows to realize ephemeral visual content (for a duration of 24 h) by identifying an influencer. It should be noted that behavioral engagement can even go as far as consumer devotion, i.e., the manifestation of his devotion to a brand with his network. Voluntary, this ambassador can influence consumers to the benefit or disadvantage of the adored brand [53].

The literature on engagement confirms both the complexity of the concept and its importance to brands. The dimensions identified underline the multifaceted nature of the subject and the variety of fields of research interest [54]. Table 1 presents the main consumer engagement measurement scales used in marketing. However, HB is not managed in the same way as an inanimate brand [55]. This confirms that the concept is not surfing on a “trendy” keyword and that having measurement tools capturing its specificities is necessary.

Table 1. Main consumer engagement measurement scales used in marketing.

| Author | Context | Dimension/Sub-Dimension | Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algesheimer et al. (2005) [12] | Community engagement | Unidimensional | 28 |

| Calder et al. (2009) [13] | Consumer engagement with a website | Stimulation and inspiration, social facilitation, temporal, self-esteem and civic mindedness, intrinsic enjoyment, utilitarian, participation and socialization, community | 37 |

| Sprott et al. (2009) [3] | Brand engagement in self-concept | Unidimensional | 8 |

| Craig Lefebvre et al. (2010) [56] | eHealth engagement scale | Involving, credible, not dull, hip/cool | 21 |

| O’Brien and Toms (2010) [57] | User engagement | Focus attention, perceived usability, aesthetics, endurability, novelty, felt involvement | 31 |

| Cheung et al. (2011) [58] | Engagement with an online social platform | Vigor, absorption, dedication to the client | 18 |

| Yoshida et al. (2014) [59] | Fan engagement in the sports context | Managerial cooperation, prosocial behavior, performance tolerance | 12 |

| Vivek et al. (2014) [60] | Customer engagement with brand | Conscious attention, enthusiastic participation, social connection | 10 |

| Hollebeek et al. (2014) [17] | Consumer engagement with brand on social media | Cognitive processing, affection, activation | 10 |

| Taheri et al. (2014) [61] | Visitor engagement | Unidimensional | 8 |

| So et al. (2014) [28] | Customer engagement with tourism brand | Identification, enthusiasm, attention, absorption, interaction | 25 |

| Kemp (2015) [18] | Client’s artistic engagement | Affective, cognitive, behavioral, social, connection | 20 |

| Vinerean and Opreana (2015) [2] | Online consumer engagement | Cognitive, emotional, behavioral | 11 |

| Dwivedi (2015) [7] | Consumer brand engagement | Vigor, dedication, absorption | 17 |

| Baldus et al. (2015) [62] | Engagement with the online brand community | Brand influence, brand passion, connection, help, like-minded discussion, rewards (hedonic), rewards (utilitarian), help-seeking, self-expression, up-to-date information, validation | 42 |

| Hopp and Gallicano (2016) [63] | Engagement with a blog | Presence, virality, utility | 12 |

| Schivinski et al. (2016) [49] | Consumer engagement with branded content on social media | Consumption, contribution, creation | 17 |

| Dessart et al. (2016) [20] | Consumer engagement with online brand communities | Enthusiasm, pleasure, attention, absorption, sharing, learning, approval | 22 |

| Hollebeek et al. (2016) [64] | Consumers’ musical engagement | Identity experience, social experience, transportative experience, affect-inducing experience | 25 |

| Calder et al. (2016) [65] | Engagement | Interaction, transportation, discovery, identity, civic orientation | 11 |

| Thakur (2016) [66] | Customer engagement | Social-facilitation, self-connect, intrinsic enjoyment, time-filler, utilitarian, monetary experience | 19 |

| Solem and Paderson (2017) [4] | Organizational behavior and consumer engagement with brand on social media | Physical, emotional, cognitive, psychological | 9 |

| Paruthi and Kaur (2017) [67] | Online engagement | Conscious attention, affection, enthusiastic participation, social connection | 16 |

| Harrigan et al. (2017) [68] | Customer engagement | Identification, absorption, interaction | 11 |

| Robertson et al. (2017) [69] | Engagement with alcohol marketing | Behavioral | 13 |

| Guo (2018) [70] | Social engagement with programming | Vertical involvement, diagonal interaction, horizontal intimacy, horizontal influence | 15 |

| Mirbagheri and Najmi (2019) [23] | Consumers’ engagement with SM activation campaigns | Attention, interest and enjoyment, participation | 12 |

| Huang and Choi (2019) [71] | Tourism engagement | Social interaction, interaction with employees, belonging, link to activity | 16 |

| Obilo et al. (2021) [5] | Consumer brand engagement | Content engagement, co-creation, advocacy, negative engagement | 21 |

| Majeed et al. (2022) [11] | Destination brand engagement | Unidimensional | 36 |

| Ho et al. (2022) [72] | Customer engagement behaviors | Influencing behaviors, participation in events, information sharing, feedback, assistance to other customers, C2C, interaction, browsing, complaints | 16 |

| Ndhlovu and Maree (2022) [73] | Consumer brand engagement | Product: Reasoned behavior, affection; Service: social connection, identification, absorption | 49 |

| Lourenço et al. (2022) [16] | Consumer brand engagement | Cognitive, emotion, behavior | 9 |

| Shin and Perdue (2022) [19] | Customer engagement behaviors | Influential-experience value, C2B innovation value, relational value, functional value | 15 |

| The present study (2023) | Influencer engagement on SM | Self-concept, attachment, consumption, contribution, creation | 21 |

5. Characteristics of the Human Brand

The HB is differentiated from traditional brands owing to its human aspect. The human brand is imbued with physical and social realities, prejudices, and limitations. Although the HB poses risks related to management of its image, it also offers advantages in terms of the potential to improve the returns on the brand [74]. In addition, the HB has a wider range of attributes than does an inanimate brand and can adapt to the circumstances surrounding it. The HB also has a significantly greater capacity for reciprocity with the consumer than a traditional brand [75]. The bond between an HB and a consumer is similar to interpersonal relationships, especially in SM [37][38]. Indeed, many followers develop a parasocial relationship with an influencer—an imaginary relationship of friendship or love towards a media person [76][77]. A parasocial relationship enhances the perceived credibility of the influencer and positively affects brand trust and follower behavior [78].

However, while HB is extremely powerful, it is also very risky. Indeed, he is not immune to the risks of adverse events such as illness or misconduct [74]. For example, in 2020, Maripier Morin (Quebec host, television columnist, businesswoman and actress) saw her empire crumble when she admitted to accusations of sexual harassment, physical assault and racist remarks. Her business partners could not appear in the scandalous image of the actress and host. She was dumped by the brands she represented. In addition, Bell Media and Videotron have removed its television programs on all their platforms [79]. The main dangers that the human body imposes on HB are mortality, hubris, unpredictability, and social entrenchment. These characteristics lend it a particularly high level of authenticity and resonance, which enhances its value from consumers’ standpoint [80]. This supports the importance of considering the living nature of HB when examining the engagement relationship [75].

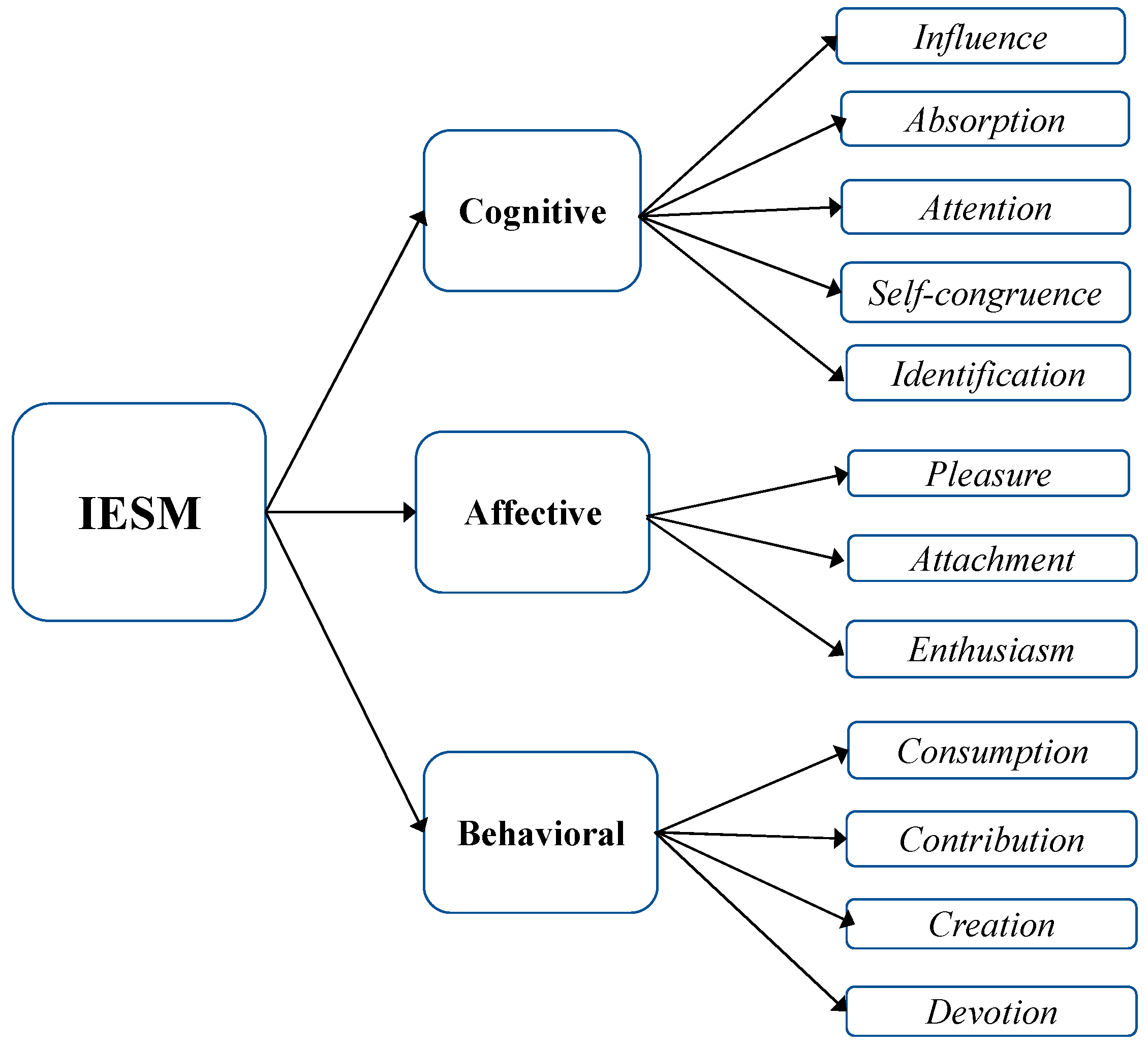

As mentioned earlier, engagement in marketing has primarily been measured in the context of the consumer-brand relationship [81]. The researchers also observe that the items used apply to the use of traditional brands and/or in specific and often offline contexts (e.g., engagement to art, [18]). Moreover, depending on the interests of the influencers, the engagement differs [82]. This calls into question the relevance of current measuring instruments for influencer on SM. Admittedly, scales applying to the context of SMs have been listed, but they are intended to measure engagement to platforms or websites [13][58], which is difficult to transfer to HB [17][83]. Additionally, the rapid consumption pattern on SMs [84] and two-way exchanges with SM suggest unique engagement process and behaviors that existing measurement tools do not capture. Due to the uniqueness of HB and the context under study, the available measurement tools are not applicable. The researchers propose the development of the Influencer Engagement Scale on Social Media (IESM). Table 2 summarizes the dimensions and sub-dimensions of engagement with an influencer and Figure 1 presents the theoretical model.

Figure 1. Theoretical model of the IESM scale.

Table 2. Dimensions and Sub-Dimensions of Engagement with an Influencer.

| Inspired by | |

|---|---|

| Cognitive dimension Set of enduring and active mental states experienced by a follower toward an influencer on SM. |

Brodie et al. (2013) [85] |

| Influence: The level of an influencer’s cognitive influence on their followers relative to the sharing of information they post on SM. | Kemp (2015) [18] |

| Absorption: A follower’s level of cognitive immersion associated with an influencer on SM. | Vivek et al. (2014) [60] |

| Attention: The degree to which a follower pays attention to and focuses on an influencer on SM. | Hollebeek et al. (2014); Vivek (2009) [17][21] |

| Self-congruence: Correspondence between the image projected by the influencer and one facet of the follower’s self-concept. | Sirgy (1982) [24] |

| Identification: Follower’s degree of affiliation with an influencer on SM and ensuing self-definition. | Bhattacharya et al. (1995); Thomson et al. (2005) [27][86] |

| Affective dimension Summative and enduring level of emotions felt by a follower toward an influencer on SM. |

Calder et al. (2013) [29] |

| Attachment: The intensity of a follower’s emotional connection to an influencer on SM. | Bowlby (1969) [87] |

| Pleasure: Pleasure and happiness derived from interactions with an influencer on SM. | Patterson et al. (2006) [88] |

| Enthusiasm: A follower’s intrinsic level of excitement about and interest in an influencer on SM. | Hollebeek (2011); Mollen and Wilson (2010) [81][89] |

| Behavioral dimension A follower’s behavioral manifestation of engagement with an influencer on SM, which varies in intensity depending on the type of interaction. |

Muntinga et al. (2011) [46] |

| Consumption: The first level of follower engagement activity with an influencer on SM: passive participation. | Schivinski et al. (2016); Muntinga et al. (2011) [46][49] |

| Contribution: The second level of follower engagement activity with an influencer on SM: contribution through interactions. | |

| Creation: The third level of follower engagement activity with an influencer on SM: creation of content about the influencer. | |

| Devotion: The highest level of follower engagement activity with an influencer on SM. This level transcends the boundaries of the Internet and may include spending money and volunteering one’s time and energy to support the follower. | Hunt et al. (1999) [90] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jtaer18040088

References

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Juric, B.; Ilic, A. Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications for Research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271.

- Vinerean, S.; Opreana, A. Consumer Engagement in Online Settings: Conceptualization and Validation of Measurement Scales. Expert J. Mark. 2015, 3, 35–50.

- Sprott, D.; Czellar, S.; Spangenberg, E. The Importance of a General Measure of Brand Engagement on Market Behavior: Development and Validation of a Scale. J. Mark. Res. 2009, 46, 92–104.

- Solem, B.A.A.; Pedersen, P.E. The Role of Customer Brand Engagement in Social Media: Conceptualisation, Measurement, Antecedents, and Outcomes. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2017, 10, 223–254.

- Obilo, O.O.; Chefor, E.; Saleh, A. Revisiting the Consumer Brand Engagement Concept. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 634–643.

- Hollebeek, L.D. Demystifying Customer Brand Engagement: Exploring the Loyalty Nexus. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 785–807.

- Dwivedi, A. A Higher-Order Model of Consumer Brand Engagement and Its Impact on Loyalty Intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 24, 100–109.

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Sarstedt, M.; Menidjel, C.; Sprott, D.E.; Urbonavicius, S. Hallmarks and Potential Pitfalls of Customer- and Consumer Engagement Scales: A Systematic Review. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 1074–1088.

- Brault-Labbé, A.; Dubé, L. Mieux Comprendre l’engagement Psychologique: Revue Théorique et Proposition d’un Modèle Intégratif. Les Cah. Int. De Psychol. Soc. 2009, 81, 115–131.

- Van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer Engagement Behavior: Theoretical Foundations and Research Directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266.

- Majeed, S.; Zhou, Z.; Kim, W.G. Destination Brand Image and Destination Brand Choice in the Context of Health Crisis: Scale Development. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 29, 81–96.

- Algesheimer, R.; Dholakia, U.M.; Herrmann, A. The Social Influence of Brand Community: Evidence from European Car Clubs. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 19–34.

- Calder, B.J.; Malthouse, E.C.; Schaedel, U. An Experimental Study of the Relationship between Online Engagement and Advertising Effectiveness. J. Interact. Mark. 2009, 23, 321–331.

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work Engagement: A Quantitative Review and Test of Its Relations with Task and Contextual Performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136.

- Kahn, W.A. To Be Fully There: Psychological Presence at Work. Hum. Relat. 1992, 45, 321–349.

- Lourenço, C.E.; Hair, J.F.; Zambaldi, F.; Ponchio, M.C. Consumer Brand Engagement Concept and Measurement: Toward a Refined Approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103053.

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer Brand Engagement in Social Media: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165.

- Kemp, E. Engaging Consumers in Esthetic Offerings: Conceptualizing and Developing a Measure for Arts Engagement. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2015, 20, 137–148.

- Shin, H.; Perdue, R.R. Developing a Multi-Dimensional Measure of Hotel Brand Customers’ Online Engagement Behaviors to Capture Non-Transactional Value. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 593–609.

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Capturing Consumer Engagement: Duality, Dimensionality and Measurement. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 399–426.

- Vivek, S.D. A Scale of Consumer Engagement. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alabama, Huntsville, AL, USA, 2009.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; HarperColl: New York, NY, USA, 1996.

- Mirbagheri, S.; Najmi, M. Consumers’ Engagement with Social Media Activation Campaigns: Construct Conceptualization and Scale Development: Mirbagheri and Najmi. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 376–394.

- Sirgy, M.J. Self-Concept in Critical Review Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 287–300.

- Schembri, S.; Merrilees, B.; Kristiansen, S. Brand Consumption and Narrative of the Self. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 623–637.

- Bagozzi, R.; Dholakia, U.M. Antecedents and Purchase Consequences of Customer Participation in Small Group Brand Communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2006, 23, 45–61.

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Hayagreeva, R.; Glynn, M.A. Understanding the Bond of Identification: An Investigation of Its Correlates Among Art Museum Members. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 46–57.

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B. Customer Engagement with Tourism Brands: Scale Development and Validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 304–329.

- Calder, B.J.; Issac, M.S.; Malthouse, E.C. Taking the Customer’s Point-of-View: Engagement or Satisfaction; Marketing Science Institute Work Paper Series; Marketing Science Institute: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 13–102.

- Dielh, S. Brand Attachment; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009.

- Bergami, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. Self-Categorization, Affective Commitment, and Group Self-Esteem as Distinct Aspects of Social Identity in the Organization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 39, 555–577.

- Brault-Labbé, A.; Dubé, L. Engagement, Surengagement et Sous-Engagement Académiques Au Collégial: Pour Mieux Comprendre Le Bien-Être Des Étudiants. Rev. Des Sci. De L’éducation 2008, 34, 729–751.

- Brault-Labbé, A.; Dubé, L. Engagement Scolaire, Bien-Être Personnel et Autodétermination Chez Des Étudiants à l’université. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2010, 42, 80–92.

- Jahn, B.; Kunz, W. How to Transform Consumers into sans of Your Brand. J. Serv. Manag. 2012, 23, 344–361.

- Rook, D.W. The Buying Impulse. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 189–199.

- Ilicic, J.; Baxter, S.M.; Kulczynski, A. The Impact of Age on Consumer Attachment to Celebrities and Endorsed Brand Attachment. J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 273–288.

- Jillapalli, R.K.; Wilcox, J.B. Professor Brand Advocacy: Do Brand Relationships Matter? J. Mark. Educ. 2010, 32, 328–340.

- McCormick, K. Celebrity Endorsements: Influence of a Product-Endorser Match on Millennials Attitudes and Purchase Intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 39–45.

- Baumöl, U.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jung, R. Dynamics of Customer Interaction on Social Media Platforms. Electron. Mark. 2016, 26, 199–202.

- Kim, N.; Kim, W. Do Your Social Media Lead You to Make Social Deal Purchases? Consumer-Generated Social Referrals for Sales via Social Commerce. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 38–48.

- Abidin, C. Communicative Intimacies: Influencers and Perceived Interconnectedness. Ada A J. Gend. New Media Technol. 2015, 8.

- Bonilla, M.D.R.; Del Olmo Arriaga, J.L.; Andreu, D. The Interaction of Instagram Followers in the Fast Fashion Sector: The Case of Hennes and Mauritz (H&M). J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2019, 10, 342–357.

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C. User Engagement in Social Media—An Explorative Study of Swedish Fashion Brands. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 177–190.

- Syrdal, H.A.; Briggs, E. Engagement with Social Media Content: A Qualitative Exploration. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2018, 26, 4–22.

- Franzak, F.; Makarem, S.; Jae, H. Design Benefits, Emotional Responses, and Brand Engagement. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2014, 23, 16–23.

- Mutinga, D.G.; Moorman, M.; Smit, E.G. Introducing COBRAs Exploring Motivations for Brand-Related Social Medias Use. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 13–46.

- Gainous, J.; Abbott, J.P.; Wagner, K.M. Active vs. Passive Social Media Engagement with Critical Information: Protest Behavior in Two Asian Countries. Int. J. Press/Politics 2021, 26, 464–483.

- Shao, G. Understanding the Appeal of User-Generated Media: A Uses and Gratification Perspective. Internet Res. 2009, 19, 7–25.

- Schivinski, B.; Christodoulides, G.; Dabrowski, D. Measuring Consumers’ Engagement with Brand-Related Social-Media Content: Development and Validation of a Scale That Identifies Levels of Social-Media Engagement with Brands. J. Advert. Res. 2016, 56, 64.

- Dholakia, U.M.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Pearo, L.K. A Social Influence Model of Consumer Participation in Network- and Small-Group-Based Virtual Communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 241–263.

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic Word-of-Mouth via Consumer-Opinion Platforms: What Motivates Consumers to Articulate Themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52.

- Schivinski, B.; Dabrowski, D. The Impact of Brand Communication on Brand Equity through Facebook. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2015, 9, 31–53.

- Pichler, E.A.; Hemetsberger, A. “Hopelessly Devoted to You”—Towards an Extended Conceptualization of Consumer Devotion. In Advances in Consumer Research; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 2007; Volume 34, pp. 194–199.

- Vuignier, R. Place Branding & Place Marketing 1976–2016: A Multidisciplinary Literature Review. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2017, 14, 447–473.

- Verčič, A.T.; Verčič, D. Generic Charisma—Conceptualization and Measurement. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 12–19.

- Craig Lefebvre, R.; Tada, Y.; Hilfiker, S.W.; Baur, C. The Assessment of User Engagement with eHealth Content: The eHealth Engagement Scale. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2010, 15, 666–681.

- O’Brien, H.; Toms, E. The Development and Evaluation of a Survey to Measure User Engagement. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 50–69.

- Cheung, C.; Lee, M.; Jin, X. Customer Engagement in an Online Social Platform: A Conceptual Model and Scale Development. In Proceedings of the Thirty Second International Conference on Information Systems, Shanghai, China, 4–7 December 2011; pp. 1–8.

- Yoshida, M.; Gordon, B.; Nakazawa, M.; Biscaia, R. Conceptualization and Measurement of Fan Engagement: Empirical Evidence from a Professional Sport Context. J. Sport Manag. 2014, 28, 399–417.

- Vivek, S.D.; Beatty, S.E.; Dalela, V.; Morgan, R.M. A Generalized, Multidimensional Scale for Measuring Customer Engagement. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2014, 22, 401–420.

- Taheri, B.; Jafari, A.; O’Gorman, K. Keeping Your Audience: Presenting a Visitor Engagement Scale. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 321–329.

- Baldus, B.J.; Voorhees, C.; Calantone, R. Online Brand Community Engagement Scale. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 978–985.

- Hopp, T.; Gallicano, T.D. Development and Test of a Multidimensional Scale of Blog Engagement. J. Public Relat. Res. 2016, 28, 127–145.

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Malthouse, E.C.; Block, M.P. Sounds of Music: Exploring Consumers’ Musical Engagement. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 33, 417–427.

- Calder, B.J.; Isaac, M.S.; Malthouse, E.C. How to Capture Consumer Experiences: A Context-Specific Approach to Measuring Engagement: Predicting Consumer Behavior Across Qualitatively Different Experiences. J. Advert. Res. 2016, 56, 39–52.

- Thakur, R. Understanding Customer Engagement and Loyalty: A Case of Mobile Devices for Shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 151–163.

- Paruthi, M.; Kaur, H. Scale Development and Validation for Measuring Online Engagement. J. Internet Commer. 2017, 16, 127–147.

- Harrigan, P.; Evers, U.; Miles, M.; Daly, T. Customer Engagement with Tourism Social Media Brands. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 597–609.

- Robertson, A.; Morse, D.T.; Hood, K.; Walker, C. Measuring Alcohol Marketing Engagement: The Development and Psychometric Properties of the Alcohol Marketing Engagement Scale. J. Appl. Meas. 2017, 18, 13.

- Guo, M. How Television Viewers Use Social Media to Engage with Programming: The Social Engagement Scale Development and Validation. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2018, 62, 195–214.

- Huang, S.; Choi, H.-S.C. Developing and Validating a Multidimensional Tourist Engagement Scale (TES). Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 469–497.

- Ho, C.-I.; Chen, M.-C.; Shih, Y.-W. Customer Engagement Behaviours in a Social Media Context Revisited: Using Both the Formative Measurement Model and Text Mining Techniques. J. Mark. Manag. 2022, 38, 740–770.

- Ndhlovu, T.; Maree, T. Consumer Brand Engagement: Refined Measurement Scales for Product and Service Contexts. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 228–240.

- Fournier, S.; Eckhardt, G. Managing the Human in Human Brands. GfK-Mark. Intell. Rev. 2018, 10, 30–33.

- Russell, C.; Schau, H.J. The Ties That Bind: Consumer Engagement and Transference with a Human Brand. In Proceedings of the ACR North American Advances, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 6–9 October 2010.

- Horton, D.; Wohl, R.R. Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction. Psychiatry 1956, 19, 215–229.

- Tukachinsky, R. Para-Romantic Love and Para-Friendships: Development and Assessment of a Multiple-Parasocial Relationships Scale. Am. J. Media Psychol. 2010, 3, 73–94.

- Reinikainen, H.; Munnukka, J.; Maity, D.; Luoma-aho, D. ‘You Really Are a Great Big Sister’—Parasocial Relationships, Credibility, and the Moderating Role of Audience Comments in Influencer Marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 279–298.

- Lemieux, M.-A. L’empire de Maripier Morin s’écroule. J. De Montréal 2020. Available online: https://www.journaldemontreal.com/2020/07/09/maripier-morin-met-ses-activites-professionnelles-sur-la-glace (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Speed, R.; Butler, P.; Collins, N. Human Branding in Political Marketing: Applying Contemporary Branding Thought to Political Parties and Their Leaders. J. Political Mark. 2015, 14, 129–151.

- Hollebeek, L.D. Exploring Customer Brand Engagement: Definition and Themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573.

- Tafesse, W.; Wood, B.P. Followers’ Engagement with Instagram Influencers: The Role of Influencers’ Content and Engagement Strategy. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102303.

- Aaker, D.A.; Erich, J. Brand Leadership; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000.

- Carah, N.; Shaul, M. Brands and Instagram: Point, Tap, Swipe, Glance. Mob. Media Commun. 2016, 4, 69–84.

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L.D. Consumer Engagement in a Virtual Brand Community: An Exploratory Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114.

- Thomson, M.; MacInnis, D.J.; Park, W.C.; Whan Park, C. The Ties That Bind: Measuring the Strength of Consumers’ Emotional Attachments to Brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91.

- Bowlby, J. Disruption of Affectional Bonds and Its Effects on Behavior. Canada’s Ment. Health Suppl. 1969, 59, 12.

- Patterson, P.; Ting, Y.; De Ruyter, K. Understanding Customer Engagement in Services. In Proceedings of the ANZMAC Conference: Understanding customer engagement in services, Brisbane, Australia, 4–6 December 2006.

- Mollen, A.; Wilson, H. Engagement, Telepresence and Interactivity in Online Consumer Experience: Reconciling Scholastic and Managerial Perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 919–925.

- Hunt, K.A.; Bristol, T.; Brashaw, R.E. A Conceptual Approach to Classifying Sports Fans. J. Serv. Mark. 1999, 13, 439–452.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!