The metaverse as a concept is not new, having been introduced in the sci-fi novel Snow Crash over 30 years ago. The metaverse is widely discussed and is generally seen to be the next “big thing” in the application of technology in business and society. A wide range of digital technologies will be deployed in the metaverse, bringing increased focus on corporate digital responsibilities that will likely require government regulation.

- metaverse

- corporate digital responsibility

- CDR

- regulation

- digital technologies

1. Concept and Definition

“Imagine a virtual world where billions of people live, work, shop, learn and interact with each other—all from the comfort of their couches in the physical world. In this world, the computer screens we use today to connect to a worldwide web of information have become portals to a 3D virtual realm that’s palpable—like real life, only bigger and better. Digital facsimiles of ourselves, or avatars, move freely from one experience to another, taking our identities and our money with us”.

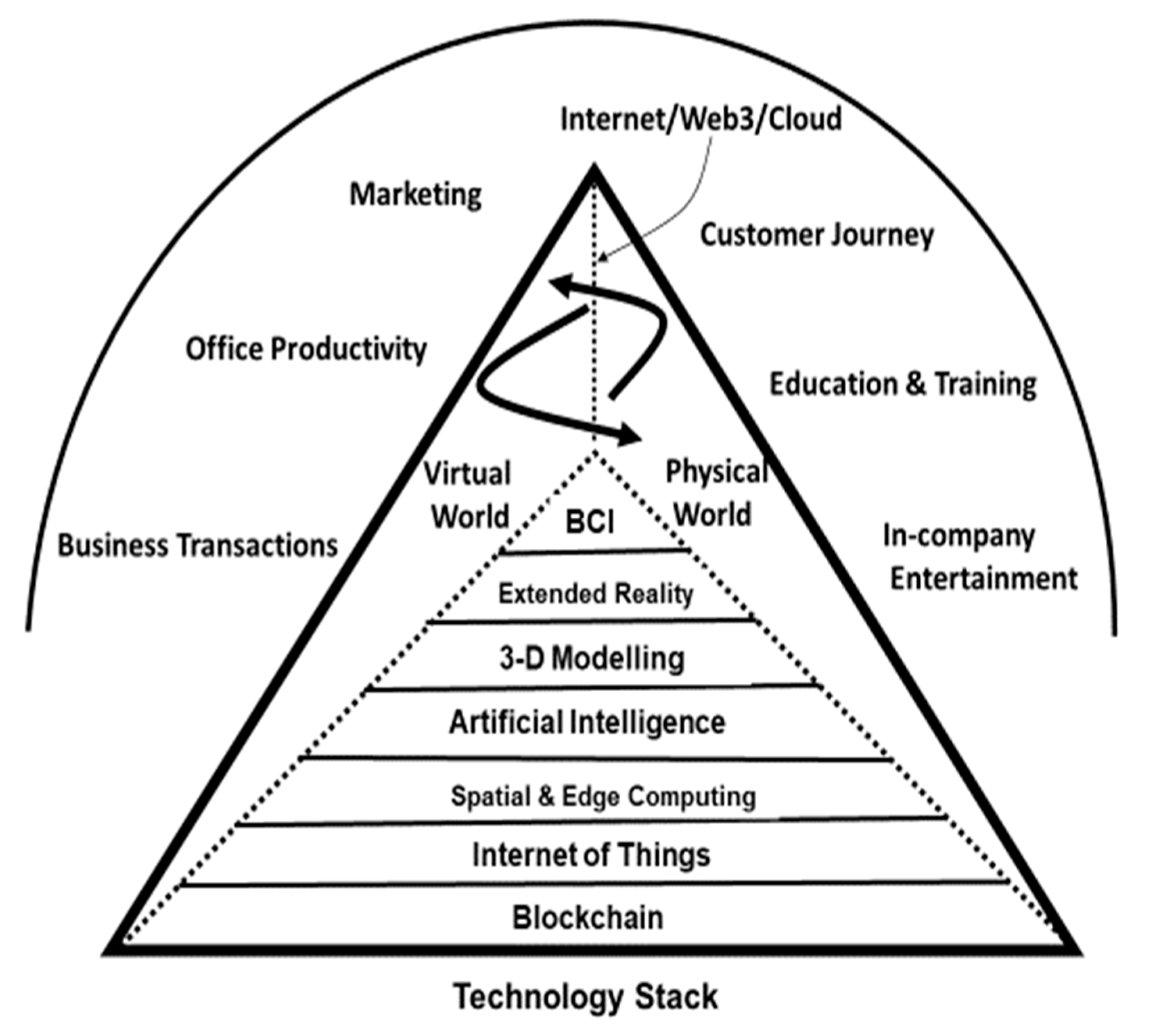

2. Metaverse Technologies and Business Applications

| Digital Technology | Role in the Metaverse |

|---|---|

| Web3 [8] | The new version of the World Wide Web, still in development, that will provide the window into the metaverse, using blockchain and artificial intelligence to support operations in both the physical and virtual worlds. |

| Brain–computer interfaces [15] | Still largely under development, these will replace or augment extended reality interfaces and provide more direct brain-to-computer connectivity. |

| Extended reality [14] | Extended reality technologies (AR, VR and MR) will be used to provide user access to the virtual side of the metaverse. Headsets and glasses will provide users with virtual reality experiences that parallel the physical world. |

| 3D modelling [13] | Three-dimensional modelling technologies will be used to create the virtual world images, products and other objects. |

| Artificial intelligence (AI) [12] | AI will be integral to the robotics functions in the metaverse, including chatbots and avatars. AI will also have wider applications to support human activities. |

| Spatial/edge computing [11] | IoT and other data will be processed in real-time to provide the information that supports the physical and virtual worlds and oils the metaverse machinery. |

| Internet of Things (IoT) [10] | A full range of devices, monitors and controllers for data collection within the physical and virtual environments. |

| Blockchain [9] | Blockchain technology will support cryptocurrency and non-fungible tokens, providing the secure and immutable storage of digital property, payments and other transactions. |

3. Risks, Responsibilities and Regulation

Figure 2. Risks (grey-shaded) and main elements of CDR in the metaverse.

4. Summary

Consideration of the responsibilities associated with the development of the metaverse and the issues surrounding them, raises as many, perhaps more, questions than it answers. While many companies may initially look to focus their strategic thinking on creating immersive marketing opportunities, expanding audience engagement, and digital advertising, if companies lose sight of their strategic responsibilities for the metaverse, and in so doing lose consumers’ trust, then they may find it increasingly difficult to reap the potential business benefits claimed for the metaverse.

Future research could profitably look into how companies are addressing their responsibilities for the metaverse. While a wide range of specific research avenues might be identified, two general themes would seem to stand out. On the one hand, it is important to develop a theoretical framework to help to locate corporate responsibility for the metaverse within the wider business and social context, and to provide a framework to underpin what will surely be a diverse and rapidly growing body of research work on corporate responsibilities for the metaverse. On the other hand, a variety of empirical studies might profitably explore how companies are addressing, introducing, and reporting on their responsibilities for the metaverse, and on consumers’ awareness, and understanding, of how companies are discharging such responsibilities.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/knowledge3040035

References

- Tucci, L. What Is the Metaverse? An Explanation and In-depth Guide; TechTarget: Newton, MA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/feature/The-metaverse-explained-Everything-you-need-to-know#:~:text=The%20metaverse%20is%20a%20vision,not%20in%20the%20physical%20world (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- McKinsey. Marketing in the Metaverse: An Opportunity for Innovation and Experimentation. 2022. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/marketing-in-the-metaverse-an-opportunity-for-innovation-and-experimentation (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Marabelli, M.; Newell, S. Responsibly strategizing with the metaverse: Business implications and DEI opportunities and challenges. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2023, 32, 101774.

- Deloitte. A Whole New World: Exploring the Metaverse and What It Could Mean for You. 2022. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/technology/us-ai-institute-what-is-the-metaverse-new.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Mystakadis, S. Metaverse. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 486–497.

- PWC. Demystifying the Metaverse. 2023. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/us/en/tech-effect/emerging-tech/demystifying-the-metaverse.html (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Mager, S.; Matheson, B. Rising Technologies for Marketers to Watch. Deloitte Insights. 2023. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/insights/topics/marketing-and-sales-operations/global-marketing-trends/2023/rising-technology-trends-for-marketing.html (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Stackpole, T. What Is Web3? Harvard Business Review. The Big Idea Series. 2022. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/05/what-is-web3 (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Huynh-The, T.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Wang, W.; Yenduri, G.; Ranaweera, P.; Pham, Q.-V.; Benevides da Costa, D.; Liyanage, M. Blockchain for the metaverse: A Review. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 143, 401–419.

- Kiran, M.B.; Wynn, M. The Internet of Things in the Corporate Environment. In Handbook of Research on Digital Transformation, Industry Use Cases, and the Impact of Disruptive Technologies; Wynn, M., Ed.; IGI-Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 132–148. ISBN 9781799877127. Available online: https://eprints.glos.ac.uk/10497/ (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Lawton, G. Spatial Computing; TechTarget: Newton, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/searchcio/definition/spatial-computing (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Jones, P.; Wynn, M. Artificial Intelligence and Corporate Digital Responsibility. J. Artif. Intell. Mach. Learn. Data Sci. 2023, 1, 50–58.

- Ripert, D. The Pathway to the Metaverse Begins with 3D Modelling; Entrepreneur Science and Technology: Irvine, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.entrepreneur.com/science-technology/the-pathway-to-the-metaverse-begins-with-3d-modelling/425643 (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Xi, N.; Chen, J.; Gama, F.; Riar, M.; Hamari, J. The challenges of entering the metaverse: An experiment on the effect of extended reality on workload. Inf. Syst. Front 2023, 25, 659–680.

- Abdelghafar, S.; Ezzat, D.; Darwish, A.; Hassanien, A.E. Metaverse for Brain Computer Interface: Towards New and Improved Applications. In The Future of Metaverse in the Virtual Era and Physical World; Hassanien, A.E., Darwiish, A., Torky, M., Eds.; Studies in Big Data; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 123, pp. 43–58.

- Pratt, M.; Daniel, D. The CIO’s Guide to Understanding the Metaverse. 2022. Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/searchcio/feature/The-essential-introduction-to-the-metaverse-for-CIOs?utm_campaign=20220316_The+CIO%27s+essential+guide+to+the+metaverse&utm_medium=EM&utm_source=NLN&track=NL-1808&ad=940624&asrc=EM_NLN_211154075 (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Accenture. Building a Responsible Metaverse. 2023. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/gb-en/insights/technology/responsible-metaverse (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Mollajafari, S.; Bechkoum, K. Blockchain Technology and Related Security Risks: Towards a Seven-Layer Perspective and Taxonomy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13401.

- Pratt, M. 10 Metaverse Use Cases for IT & Business Leaders. Computer Weekly.com E-guide. 2022. Available online: https://www.computerweekly.com/ehandbook/10-metaverse-use-cases-for-IT-and-business-leaders (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Capgemini. The Metaverse—Opportunities for Business Operations. 2023. Available online: https://www.capgemini.com/insights/research-library/the-metaverse-opportunities-for-business-operations/ (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Collins, C. Looking to the Future: Higher Education in the Metaverse. Educ. Rev. 2008, 43, 50–52.

- Purdy, M. Building a Great Customer Experience in the Metaverse. Harvard Business Review. 3 April 2023. Available online: https://hbr.org/2023/04/building-a-great-customer-experience-in-the-metaverse (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Choder, B. Meetings in the Metaverse: Is this the Future of Events and Conferences? Forbes. 13 January 2022. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescommunicationscouncil/2022/01/13/meetings-in-the-metaverse-is-this-the-future-of-events-and-conferences/?sh=1d2089728a1f (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Lee, C.W. Application of Metaverse Service to Healthcare Industry: A Strategic Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13038.

- Nichols, S. Metaverse Rollout Brings New Security Risks, Challenges. 2022. Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/searchsecurity/news/252513072/Metaverse-rollout-brings-new-security-risks-challenges (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Rosenberg, L. Regulation of the Metaverse: A roadmap: The Risks and Regulatory Solutions for Largescale Consumer Platforms. 2022. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3546607.3546611?casa_token=nzlplVhYPnUAAAAA:fWQ9iX6aNy0PaW_-69iRVgITMoXMlDy62gSSVHTBUgLCWbwS3oDnLH9mLX-B_hnqXUtYuTKI2Zy1lA (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Charamba, K. Beyond the Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights in the Dawn of a Metaverse. Univ. Miami Int. Comp. Law Rev. 2022, 30, 110–149.

- De Giovanni, P. Sustainability of the Metaverse: A transition to industry 5.0. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6079.

- Schobel, S.M.; Leimeinster, J.M. Metaverse platform ecosystems. Electron. Mark. 2023, 33, 12.

- Benjamins, R.; Vinuela, Y.R.; Alonso, C. Social and ethical challenges of the metaverse. AI Ethics 2023, 3, 689–697.