The success of energy transition relies on what happens in the contact zone, the area between citizens and municipality governments, which still awaits more thorough research. Contact zones are an issue studied mainly in the humanities, although one can also find applications of the concept to the study of human relations with animate and inanimate nature. However, these ideas are basically unknown in economics, social sciences, technical sciences, and natural sciences.

1. Introduction

Contact zones, like the transformation itself, are complex systems that cannot be studied by analytical methods alone. These zones contain many different quantitative, qualitative, tangible, and intangible elements, some of which have not yet been fully explored by the scientific fields to which they belong. These are primarily people, the expectations of individuals, local communities and entire nations, as well as the economy, energy law, technology, and many elements of animate and inanimate nature. Since contact zones are most often terra incognita in science, except, of course, in the humanities, this must lead to the conclusion that current knowledge of the energy transition has overlooked many important and critical elements for the development of renewable energy. By introducing contact zones into science, the humanities can contribute to achieving such important goals for humanity as limiting global warming and preventing climate change.

2. Contact Zones in Science

2.1. Definition of the Contact Zone and Its Most Important Elements

The concept of the contact zone was introduced by Mary Louise Pratt to denote an area where different cultures can communicate, where linguistic and cultural meetings take place, where negotiations are conducted, or even where battles are fought to determine the common history and relations of power. Contact zones should be understood as

social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out in many parts of the world today [1].

This concept has a lot to do with colonialism, so it can be treated as a synonym for the colonial frontier

[2] (pp. 6–7). Explaining the emergence of contact zones, Pratt refers to a manuscript from 1613 written in two languages, Quechua and Spanish, by Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala and titled

The First New Chronicle and Good Government. In 1908, it was discovered by the German scholar Richard Pietschmann as he was viewing the collection of the Danish Royal Library. The manuscript was intended by the author, whose origin was Andean, as a letter addressed to King Philip III of Spain, in which, as an indigenous subject, he described the history of the conquest of the Inca Empire by the Spanish, waged harsh criticism of their colonial rule, and also presented principles of good governance of the country. The document is an extensive work, with a total of 1200 pages and containing 398 full-page illustrations, but it is not known whether the king ever received it. The Danish Royal Library has produced a high-quality digital facsimile of the original manuscript, along with a transcription that is now available online

[3]. In addition, the English translation of the manuscript by Roland Hamilton is recommended to the reader

[4]. An interesting two-volume edition of the work in Spanish with transcription, prologue, notes, and chronology developed by Franklin Pease García

[5] also exists.

Nowadays, it is worth noting that Guamán Poma describes in his letter the basic principles of good governance, by which he understands the combination of Incan social and economic organization with European technical thought and Christian theology, to be adapted to the practical needs of the Andean nations

[6]. His views on political issues were complex, but systematic, coherent, and unequivocal. He was not a supporter of colonialism and the direct rule of foreigners, instead supporting native rule and calling for the restoration of traditional Andean governance and the restitution of Andean lands and properties. He condemned the greed of both civil and ecclesiastical officials. For this reason, his views can be considered anticlerical, although, on the other hand, among his postulates was the institutionalization of the Christian religion. In his eyes, the Andeans were civilized Christians, while the Spaniards he regarded as lost sinners. He called for the creation of a sovereign Andean state, which would form part of a universal Christian empire ruled by the Spanish king. It is worth noting here that despite harsh criticism of the unjust and exploitative Spanish rule, he does not reject the Spanish king because, according to the New Testament view, he believes that all power comes from God. As Rolena Adorno aptly sums up,

Guamán Poma was anti-Inca but pro-Andean, anticlerical but pro-Catholic [7].

Pratt cites this text as an example of a standard product of a contact zone, as Guamán Poma can be considered an intermediary and mediator in negotiations between native Peruvian and Spanish colonial societies and institutions. This illustrates the sociocultural and economic complexities resulting from the conquest of the Inca empire by the Spanish. The Andean author chose the title of his work with deliberation because the chronicle was the main writing apparatus for the Spaniards, which they used to present their American conquests. He decided to appropriate the official Spanish genre and use it for a new description of the history of the Christian world, in the center of which he placed the Andean peoples, not the European peoples, and where Cuzco took the place of Jerusalem. In this way, the chronicle of Guamán Poma became what Pratt calls an autoethnographic text, which means

a text in which people undertake to describe themselves in ways that engage with representations others have made of them [1]. Ethnographic texts are characterized by descriptions of how European metropolitan subjects present themselves to their others, i.e., mainly conquered peoples. On the other hand, autoethnographic texts are responses to the former prepared by such defined others or intended to enter into dialogue with them. In other words, in the first type of text, the oppressed societies are presented in a certain way by the colonizers, while in the second, the tables are turned, and the colonized peoples and cultures selectively cooperate with the literary genres and idioms of the metropolis, thus appropriating them. These elements are combined with indigenous idioms, as a result of which self-representations are created, entering into metropolitan modes of understanding in order to change them.

Another phenomenon existing in the contact zone is transculturation, meaning the process of selective and creative use by the conquered or marginalized peoples of dominant or metropolitan culture. Subjugated peoples do not have an influence on what reaches them from the metropolitan culture, but they can decide what elements they will transfer to their own culture and what purposes they will use them for

[1][2]. This term was introduced by Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz to denote cultural change during which something is always given in exchange for what is received. During this give and take, two sides of the equation are modified. Transculturation, within the meaning of Ortiz, does not mean the necessity of adapting one culture to another, but the cooperation of both active cultures, contributing to the creation of a new civilizational reality, which is exemplified by the Cuban counterpoint of two commodities, tobacco and sugar, the first of which is native and the second brought in from the outside

[8].

The contact zone is a place where cultures that have so far developed independently, and thus had distinct geographical locations and histories, now meet, establish lasting relationships, and create a new society, often of a colonial nature, in which there may be fundamental inequalities, coercion and insurmountable conflicts. In the contact zones created by invasion and violence, there is a struggle for interpretive power regarding the perception of culture, which takes place in the conditions of radical heterogeneity, ambiguities, and enormous difficulties in determining the meanings of key elements of the experienced reality. It should be noted that contemporary Indigenous peoples, unlike the Western world, identify their culture with survival. Therefore, in such a system, being “different” means for them the need to play the role of a double agent and living in a bifurcated world. In order to survive, one should create oneself as a “self” for oneself, while for the colonizer, one should create oneself as an “other”. In the contact zones, there is also the issue of self-determination of Indigenous peoples, meaning the possibility of controlling the conditions in which they will shape their relations with the nation-state or the world economy. For this reason, they are an arena of fierce negotiations concerning the mutual obligations of the conquerors and the conquered, and culture itself may also be the subject of negotiations. Relations between colonizers and the colonized are the medium from which culture, language, society, and consciousness are formed

[9].

2.2. Contact Zones in the Humanities

It follows from the definition of the contact zone that negotiations are an important element of it, as only they allow for a compromise and coexistence of different cultures and societies. However, the existence of strong negotiating potential in contact zones is sometimes considered questionable since they are based on contact languages that, although ensuring survival, have lower symbolic and personal values for users than native languages. These zones do not give an accurate answer to the question of how cultural and political differences can be articulated and negotiated in order to avoid battle. It is also pointed out that Pratt does not explain how a public space is created in which people have a reason to negotiate with competing views or factions. Therefore, there is a danger of treating contact zones as a multicultural bazaar, where opposing views are presented in a harmless way and there is no conflict between them. The missing elements of the contact zone are, therefore, factors indicating a conflict, i.e., the mutual interpenetration of competing perspectives based on the multidirectional flow of information

[10]. For this reason, it is proposed that the contact zone be reconceptualized and recognized as a forum whose functioning is maintained by continuous negotiations, interactions, and compromises between perspectives and individuals. Its essence is, therefore, a dispute over the differences regarding competing interests and views

[11]. It is also proposed that the negotiations be looked at as a form of civil dialogue, which is possible when the will to compromise is shared by all parties. In such cases, the languages and protocols of negotiation are usually determined by the dominant groups and should therefore be placed in specific historical and political dimensions

[12]. Civil dialogue must be preceded by the acquisition of real power relations, i.e., a strict definition of social roles and their immunity from routine questions about their legitimacy

[13] (p. 236).

The concept of the contact zone has found many applications in the humanities, and it is particularly useful in various pedagogical spaces

[14]. This idea can be used in research on multiculturalism

[15][16], and giving it historical significance and organizing English studies around a concept thus defined allows for a significant improvement in teaching, which at the same time reduces the focus placed on literary or chronological periods and racial or gender categories

[17]. It is also useful in museology, as it includes cultural actions, creations, and transformations of identities, all of which run along controlled and intercultural frontiers emphasizing the existence of nations, peoples, and locales. Museums should be understood as contact zones in which things and people move, not as centers or destinations

[18]. There are also concerns that the neo-colonial nature of these contact zones has a negative impact on the empowerment of the source communities whose patrimonies are exhibited, which, after all, should be the fundamental purpose of museums. Some hold the opinion that the restoration of the colonial character of the museum as a contact zone results from the role of autoethnography as an instrument of appropriation

[19]. Apart from the above, discursive contact zones are used to describe non-local and non-physical spaces in which differences and similarities between different environments of devotional fitness, both Christian and non-Christian, are negotiated

[20].

2.3. Contact Zones in Environmental Studies

The original concept of the contact zone can be extended by including political ecologies, multispecies ethnography, and more-than-human geographies, which makes it both a method and a scientific theory extremely useful in environmental studies. Thus, key issues such as creating knowledge about the environment, nature management, and counteracting the exclusive governance of wildlife may be at the center of interest. In places where the environment is managed and explored, transformational processes take place, characterized by co-presence and unpredictability, and may also result in intimate violence. The more-than-human contact zones can help achieve three overlapping aims: finding a better explanation of non-human agency by taking multiple perspectives into account, preventing acts of violence and injustice, and facilitating the decolonization of the knowledge production process.

These interdisciplinary contact zones are dynamic, taking into account rhythmic patterns, phases, and ephemeral phenomena, by which they enable the study of variable human relations with the environment. Such an approach combines many important elements into a holistic unity, the most important of which are environmental and extended geographical research, postcolonial studies, and decolonization projects

[21]. The inter-species contact zones involve interactions between people and other forms of life and, unfortunately, often asymmetrical encounters between capitalism and non-human nature, coercion, exploitation, neglect, destruction, violent oppression, wrongdoing, and other types of threats. Currently, these spaces serve to link together various phenomena, such as biodiversity conservation, climate change, and energy transition, which until recently have been the subject of separate policy discourses, now greatly increasing the ability to manage them. Due to the transformative nature of these zones, they should be places where environmental policy properly shapes and renegotiates existing relations and where effective sustainable development programs are implemented

[22]. The contact zone, when extended to environmental, geographical, and biological elements, has many potential implementations.

Helen F. Wilson uses the concepts of the encounter and the contact zone as an analysis tool in research on multispecies scholarship and, for this purpose, refers to the documentary series on biological life in the oceans

[23]. Multi-species contact zones located in the deep sea are the arena of struggles between filmmakers and technology, knowledge, various life forms, and natural phenomena in asymmetrical and changing power relations. It turns out that filmmaking of this type is ambivalent because although it shapes environmental awareness and consumer behavior, it also poses a threat to the oceans by initiating the development of maritime tourism and encouraging further exploration. Journeying across the seas in search of places beyond the human imagination and new underwater worlds waiting to be discovered has an undeniable imperial subtext, as it entails the inclusion of these marginal spaces into a realm of authority. Thus, it is a form of anti-conquest, i.e., a strategy of representation foregrounding gestures of innocence, whose task is to divert attention from the simultaneous pursuit of hegemony

[2] (p. 7). Thus, oceanic contact zones are filled with extremely complex interactions involving humans, many species of animals, marine organisms and plants, and elements of inanimate nature. Technology imposes a means of contact by removing barriers between the benthic zone and the viewers

[23].

Another more-than-human contact zone is discussed by Jenny R. Isaacs, focusing on people dealing with migratory shorebird conservation in the Delaware Bayshore in New Jersey’s Cape May County

[24]. On the beaches of this area, there are human–shorebird encounters whose asymmetry is a source of imperial domination and violence. During some stages of conservation research, such as bird banding, there is often aggression and brutality. This is interpreted as an expression of animality/coloniality, namely, reductive conceptions of the animal, common to colonialism and nature protection. The progressive globalization of nature conservation defines the ways in which this phenomenon manifests itself. Animality/coloniality may appear or disappear in a multispecies contact zone when face-to-face encounters occur and touch is practiced. This also illustrates the conservation paradox of interpreting harm as care, which is an example of conspicuous innocence in the field of bird and nature conservation. It occurs when there is a need to use force so that the bodies of individual birds can be marked and described in the name of the higher goal of survival of the entire species. In this approach, nature protection is presented as a neo-colonial form of anti-conquest, which is a confirmation of Western European authority and control using new definitions of care and concern. The phenomenon of anti-conquest can also be an expression of settler moves to innocence. Remote monitoring technologies are a new craft of the contact zone, as they allow an expansion of the encounter space and extend control over species, space, and time, even to the entire hemisphere. The contact zone concept is useful as an aid in developing harm reduction strategies that may arise during nature conservation activities

[24].

Another development of the idea of the contact zone in environmental research is the intertidal contact zone studied by Aurora Fredriksen

[25]. The interspecies meeting place in question is the Bay of Fundy’s Minas Passage in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, where extreme tides occur, having the largest range in the world. It is a very dynamic environment, as an average flood tide in the Bay of Fundy brings 14 billion tons of seawater, which crosses the Minas Passage, 5 km wide, and flows into the Minas Basin. The speed of tidal currents in the passage may exceed 10 knots, i.e., 5 m/s. The potential for renewable energy generation here was estimated at 7000 megawatts, so it is not surprising that it is attractive for the governments of Canada and Nova Scotia in their attempts to decarbonize their energy systems. Underwater turbines located in the path of tidal streams enable the transformation of tidal energy into electricity. However, there is a serious problem with the fact that, along with the massive flood tides flowing through the narrow Minas Passage, a huge number of fish and other marine animals are pushed in and out of the pool twice a day, being the primary source of livelihood for many local fishermen. In the newly created tidal energy industry, environmental assessments, which determine the impact of underwater turbine work on marine fauna and flora, are still incomplete despite the intensive work of scientists. Fredriksen studied the generation of environmental knowledge in two contact zones. The first zone is the fishing contact zone, which is variable and constantly recreated during direct and natural meetings of traditional fishers with marine wildlife. The second zone, the scientific contact zone, includes researchers’ meetings with marine organisms, staged and remote, since they are mostly mediated by technology. In these two contact zones, two types of knowledge are produced, which overlap only to a small degree. Practical ecological knowledge acquired by anglers collides with scientific knowledge focusing on the pursuit of objectivity and detachment

[25]. The usefulness of Pratt’s concept is revealed here in two important ways related to the creation of knowledge in more-than-human contact zones. The first concerns embody cognition and thus take into account the ways in which bodies are involved in meetings, while the second indicates that cognition and action in contact zones are connected with unequal power relations. In the intertidal contact zone, it is therefore necessary to take into account the possibilities and limits of the two ways of learning, one of which assumes direct contact with marine animals and the other does not. It is to be expected that the importance of embodied knowing will increase with the intensification of ecological changes. This explains why, for many people working and living in the region, underwater turbines are an unwanted intrusion that can disrupt existing ecological relations in the bay.

3. Basic Elements of Energy Transition

3.1. Digitalization as a Driving Force of Energy Transition

Digitalization can improve electricity services and optimize the use of energy infrastructure by eliminating gaps in connection to the power grid, the cost of provision, and power supply quality, among others [26] (p. 19). In addition, the digitalization of public administration can optimize control and regulatory activities throughout the economy, which also increases the efficiency of the energy sector. Three contemporary trends, i.e., electrification, decentralization, and digitalization, create complex chains of events in the form of a virtuous cycle and, based on the positive feedback loops existing there, reinforce each other’s impact [27]. The share of electricity in the production of renewable energy is constantly increasing, as a result of which the electrification of large sectors of the economy, mainly transport and heating, is particularly important in terms of reducing carbon dioxide emissions. Decentralization is caused by a decrease in the cost of electricity production from renewable sources, which results in the conversion of consumers, until recently passive actors on the energy market, into prosumers, i.e., active participants in this market. In turn, digitalization strengthens the other two trends, contributing to the creation of a smart electricity system, of which an integral part is the smart grid, enabling the bi-directional flow of electricity and information as well as automated operation of the system in real-time.

A distinction should be made between digitization and digitalization. Digitization means the conversion of analogue data into digital data by information and communication technology, while digitalization has a much broader meaning and refers to the digital transformation of both technology and business models and processes

[26][28]. For this reason, digitalization creates additional opportunities for creating value and, thus, is a new source of revenue for enterprises. In addition, and most importantly, it is a major factor in the development of the energy system, as it enables the introduction of energy from distributed generation into it

[29]. Digitalization is also the source of the phenomenon of convergence, understood as the simultaneous development of such fields as electricity production (including the growing role of prosumer power generation), heating, communication, mobility, and intelligent buildings

[30].

3.2. The Contact Zone as the Birthplace of Digitalization

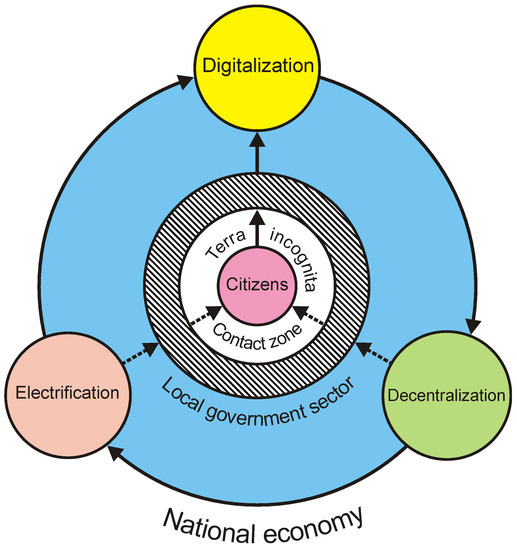

Figure 1 shows the most important dependencies in the modern economy from the point of view of the energy transition. Citizens, mostly middle-class, play a central role here, as they can make a decisive contribution to achieving climate goals. The light purple circle in the middle of the figure denotes them. Citizens can influence the energy transition via the local government sector, which has been marked with a hatched ring. The elements representing these two groups of actors do not come into direct contact with each other due to their distinctiveness; hence, mutual communication requires the existence of a certain intermediary space. Encounters between citizens and representatives of the municipal governments take place in the contact zone represented by the white ring. It is now almost literally terra incognita due to the fact that there is basically no research on the role and importance of this zone in the context of renewable energy development and climate protection.

Figure 1. Forces driving the modern economy. The influence of citizens (middle class) on public administration causes the introduction of digital prosumption into this sector, which initiates a virtuous cycle involving digitalization, decentralization, and electrification.

As indicated by the arrows in Figure 1, the influence of citizens on energy transition takes place via the local government sector, and the meeting of both parties takes place in the contact zone. This is the place where critical changes take place; it is there that all this economic machinery is ignited and put into operation, but this will not be possible without civic initiatives and decisive civic action. Polish citizens have extensive experience in the field of digital prosumption, derived from the market sector, and expect the same from services provided by public administration. Unfortunately, to date, there remains a large asymmetry between the market sector and the local government sector in terms of the implementation and use of digital technologies. The market sector is already in a new phase of capitalism called prosumer capitalism, while the local government sector is still stuck in producer and consumer capitalism. Under these circumstances, citizens are taking steps towards the digitalization of the municipal public administration in order to change its business models and procedures to be more friendly and open to the needs of local communities. This is symbolized by a continuous upward arrow that runs through the white ring of the contact zone. Typically, these activities meet with the understanding of the authorities and, depending on the financial possibilities and other conditions, are implemented sooner or later. The support of digitalization by the local government is symbolized by another continuous arrow pointing upwards and running through the blue circle of the national economy. Digitalization is the most important element of change, as it enables the decentralization of the energy sector and its shift to renewable sources. This phenomenon is indicated by a semi-circular arrow running around the perimeter of the large blue circle, from the yellow digitalization circle to the green decentralization circle. As a result of decentralization, electricity generation becomes cheaper, which allows the electrification of the most important sectors of the economy. This is indicated by another semi-circular arrow running from the green decentralization circle to the pink electrification circle. The entire cycle is closed by the last arrow connecting the pink electrification circle with the yellow digitization circle. This is because electricity is the basis of digital technologies. In this way, a virtuous cycle is created, where individual elements reinforce each other’s effect. Notably, decentralization and electrification have a return impact on citizens through the local government sector, which is symbolized by dashed arrows. The place where these critical relationships operate is the contact zone.

4. Types of Contact Zones in the Energy Transition

Filling out the area marked in Figure 1 as terra incognita, i.e., defining the contact zone between citizens and the municipal governments, requires describing the types of meetings that take place here. Furthermore, economic models and processes that change under the influence of digital technologies must be taken into account. It is also important to define the purpose of these meetings. This is a similar situation to the previously discussed case of using the contact zone concept in environmental studies concerning prescribed burns, where it functions as a dual method.

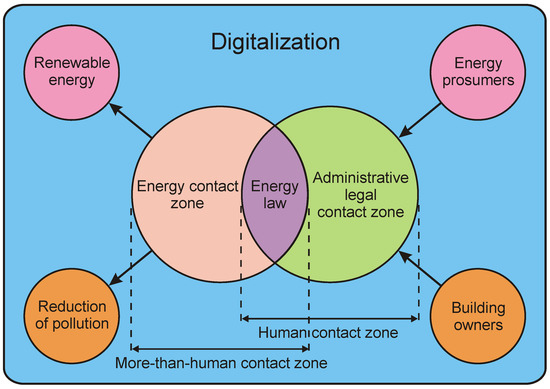

In the contact zone shown in Figure 1, there are encounters and struggles between citizens and representatives of the local government sector, which are supposed to lead to the optimal fulfilment of set climate goals on the local, national, and international scales. As shown in Figure 2, this zone has a dual character as it consists of two partially overlapping contact zones. One of these can be called the human contact zone, while the other is the more-than-human contact zone. The light green circle shows the administrative legal contact zone, in which encounters happen between citizens on the one hand and the legal system and municipal governments on the other. The light pink circle symbolizes the energy contact zone, which is the place where people meet with the energy system, the legal basis for its functioning, and the broadly understood ecology. The intersection of these circles, marked in purple, represents the energy law, which regulates the principles of energy production and their compliance with current climate objectives.

Figure 2. Types of contact zones in the energy transition.

In the administrative legal contact zone, legal solutions are being worked on to facilitate the development of the renewable energy sector and climate protection through the renovation of the building stocks. Broadly, legal contact zones are such zones

in which rival normative ideas, knowledge, power forms, symbolic universes and agencies meet in unequal conditions and resist, reject, assimilate, imitate, subvert each other, giving rise to hybrid legal and political constellations in which the inequality of exchanges are traceable [31] (p. 449).

In the course of interaction with administrative legal processes, citizens learn about the structures of state power, the prevailing logic of governance, and ways of improving it. They try to modify their exercise of political liberal rights by using legal and administrative tools and discourse, as appropriate. Past experience indicates that struggles in this contact zone may take place both within formal institutional channels and outside them

[32].

In the energy contact zone, citizens encounter both what is human and what has a more-than-human character. An integral part of this zone is the energy law, which deals with problems related to energy production and its impact on the environment, relations of prosumers with energy companies, renewable energy sources, human–natural relations, environmental issues, preserving biodiversity, reducing pollutant emissions, meeting climate goals, and issues related to energy efficiency in buildings. As mentioned above, the middle class, particularly energy prosumers and building owners, have a big role to play here. The two groups have different goals. Energy prosumers specialize in the production of energy from renewable sources, while building owners focus on using the latest construction techniques to increase the energy efficiency of their buildings.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/en16083560