Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Neurosciences

Medication-overuse headache (MOH) is a secondary headache that is classified by the third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders as a group of headaches attributable to the administration or discontinuation of various substances. MOH occurs more than 15 days per month in patients with preexisting headaches. It occurs as a result of regular (at least 3 consecutive months) overuse (10 or 15 days, depending on the type of medication) of drugs used as acute or symptomatic headache therapy.

- medication-overuse headache (MOH)

- headache

1. Epidemiology

The estimated global prevalence of medication-overuse headaches (MOHs) is about 3%. MOH is one of the most common secondary headaches, affecting approximately 80 million people worldwide [2,3]. In tertiary care centers, 50% of headache patients suffer from MOH. This type of headache more commonly occurs in women (2:1 to 5:1) and typically occurs between ages 30 and 50 of life [4,5,6,7,8]. It can also occur in the pediatric population, but there are not many epidemiological studies that have approved that. MOH is more prevalent in urban areas (14.5% versus 2.1%) [9]. Some studies have shown that the prevalence of MOH is higher in people with lower socioeconomic status [10]. The prevalence of MOH is higher in patients receiving social assistance (11%), in people who have recently retired (7.5%), and in those on frequent absenteeism and sick leave (6%) [11]. A higher prevalence of MOH was also found in migrants [12,13,14]. Despite studies, there is no clear evidence of an association between lifestyle factors such as smoking, obesity, or physical inactivity and the development of MOH [15,16,17,18].

In terms of negative impact on daily, individual, and social activity, as well as the life quality of patients and their living and work environments, MOH is highly ranked. Measuring through years of life with disability (YLDs), MOH ranks 18th among all investigated causers [19,20]. The negative effects of MOH on the patient are far greater than the negative influence of migraine or tension-type headaches [21,22,23]. MOH has significant negative effects on education, career, monthly income, and social activities [24]. MOH is one of the most expensive headaches and the most expensive disease in general [25]. This burden of MOH could be prevented by early identification of patients with primary or secondary headaches who are at risk for developing MOH, which could provide more efficient treatment and a multidisciplinary approach to prevention.

2. Pathophysiology

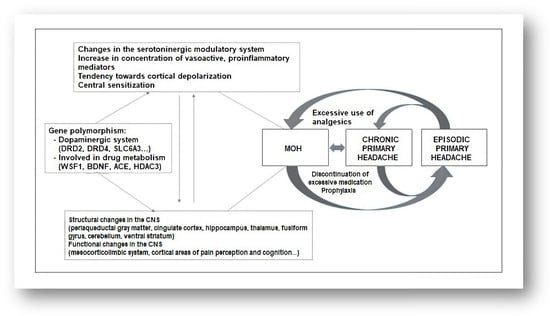

The pathophysiology of medication-overuse headaches (MOHs) is not fully understood. In addition to factors related to previous headaches, psychological factors, personality traits, and a genetic predisposition play important roles [26,27] (Figure 1). Genes involved in complex processes of endogenous pain modulation, drug metabolism, and the serotonin and dopamine systems have been linked to the development of MOH [28]. Excessive use of analgesics leads to facilitation of supraspinal pain transmission [29] (Figure 2). Functional neuroimaging studies have revealed structural and functional abnormalities in various structures responsible for processing painful stimuli and in structures that provide the neurobiological basis of affective and addictive behaviors, such as the mesolimbic system [30] (Figure 1). While cessation of excessive medication use leads to a loss of these changes in some patients, they persist long-term in others. This is understood as a kind of predisposition to the development of medication overuse [31]. Experimental studies have shown that excessive use of medications to treat migraine leads to changes in descending pain modulation pathways and that these changes are associated with a decrease in serotonin levels and a decrease in the density of certain opioid receptors [32]. There are numerous experimental, genetic, structural, and functional neurovisualization and electrophysiological studies addressing the pathophysiology of medication-overuse headache (MOH). Experimental studies have shown that chronic exposure to sumatriptan leads to a reduction in the stimulus threshold and a sustained increase in the likelihood of cortical depolarization [33,34,35]. Increased production of CGRP, substance P, and NO in the trigeminal ganglion has been demonstrated in MOH [36,37], characterized by a reduction in the nociceptive threshold and inhibitory mechanisms [38]. Chronic use of analgesics leads to increased neuronal excitability in the amygdala complex, which may explain the occurrence of anxiety and depression in MOH [39]. In MOH, the activity of the serotonergic pain modulation system is impaired, with reduced production of serotonin in the CNS and increased expression of the pronociceptive serotonin receptor (5HT-2A) [40,41,42]. In animal models, increased expression of 5HT-2A receptors on platelet membranes and decreased serotonin concentration in these cells have been demonstrated with excessive use of analgesics [43] (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Pathophysiology of MOH.

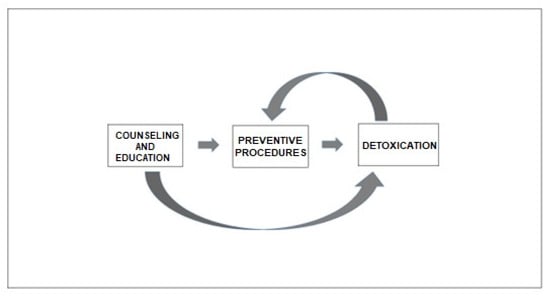

Figure 2. Algorithm for treating MOH.

Genetic studies suggest the possible importance of polymorphisms in genes related to the dopaminergic system (DRD4, DRD2, and SLC6A3) and genes involved in the neurobiology of the addiction syndrome (WSF1, BDNF, ACE, and HDAC3) [11] (Figure 1). Central sensitization plays a key role in the pathophysiology of chronic migraine [44]. Analysis of somatosensory evoked potentials has shown that patients with chronic migraine have cortical hyperexcitability compared to healthy controls and patients with episodic migraine [45,46]. A follow-up study has observed that central sensitization is reduced with the cessation of overuse of medication [47]. Neuroimaging studies in patients with chronic migraine demonstrate increased gray matter volume in the periaqueductal gray region, posterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, fusiform gyrus, cerebellum, and ventral striatum [48]. Decreased gray matter volume has been observed in the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, occipital gyri, insula, and precuneus [49]. These structures are involved in endogenous pain modulation, cognition, and affective and addictive behavior [50]. Changes in white matter volume have been observed in the insular cortex and parietal operculum, but these findings have been inconsistent across different studies [51,52].

Functional neuroimaging studies have shown functional changes in regions involved in nociceptive processes, such as the mesolimbic reward system, the fronto-parietal system, and other regions [53,54]. The mesolimbic system consists of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the accumbens region, the substantia nigra, and the ventral tegmental area, which show altered functions in MOH. These findings have been associated with the occurrence of psychiatric comorbidities in MOH [55,56]. The described changes may be reversible after discontinuation of excessive medication [57]. Positron emission tomography (18F-fluorodeoxyglucose) has been used to demonstrate hypometabolism (during excessive medication use) in regions involved in pain processing, which returned to normal after successful discontinuation of excessive medication use with analgesic therapy. There was also a decrease in metabolic processes in the orbitofrontal region after the discontinuation of excessive drug use [58]. A decrease in gray matter volume in the orbitofrontal region was associated with a higher number of headache days per month after discontinuation of excessive medication use. Unsuccessful discontinuation of excessive medication use was associated with a reduction in the volume of the orbitofrontal region before discontinuation [59]. Successful discontinuation of excessive drug use resulted in a reduction in previously increased gray matter volume in the brainstem, whereas no such changes were observed with unsuccessful discontinuation [60]. Dysfunction of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex is potentially reversible and related to headache, whereas dysfunction of midbrain dopaminergic structures is long-term and likely related to excessive drug use [55,57]. The numerous structural and functional changes in the nociceptive system observed in the studies conducted suggest that there is a neurobiological basis for MOH (Figure 1).

3. Risk Factors

The risk of developing medication-overuse headache (MOH) is lower with excessive use of triptans and ergotamine than with combined analgesic therapy and opioids [58]. Another study showed that excessive use of barbiturates and opioids carries a two-fold higher risk of developing MOH compared with triptans and nonopioid analgesics. This study showed that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may play a protective role in headache chronification in patients with a lower number of headache days per month. However, it has been shown that they may also accelerate chronification in patients with more headache days (>10 days) per month [59]. Although MOH can occur from any type of headache, it most commonly arises from the chronicity and transformation of migraine [60]. Patients with other painful conditions who are overmedicated for pain may not develop MOH unless they have had prior headaches [61,62]. In a prospective study involving 25.596 patients without chronic headaches, only 201 (0.8%) developed MOH 11 years later [63]. This study showed that risk factors for the development of MOH included the use of tranquilizers, the presence of other pain syndromes, mostly skeletal-muscular, the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, the presence of depression and anxiety, physical inactivity, and smoking. Migraine and a higher number of headache days per month were found to be risk factors. Nonmodifiable risk factors include age (<50 years), female sex, and a lower education level. Some risk factors for chronic headache have also been identified (smoking and physical inactivity), but they lead to MOH only in association with overuse of analgesics [64]. A family history of MOH or substance abuse (alcohol, etc.) increases the risk of developing MOH threefold [65].

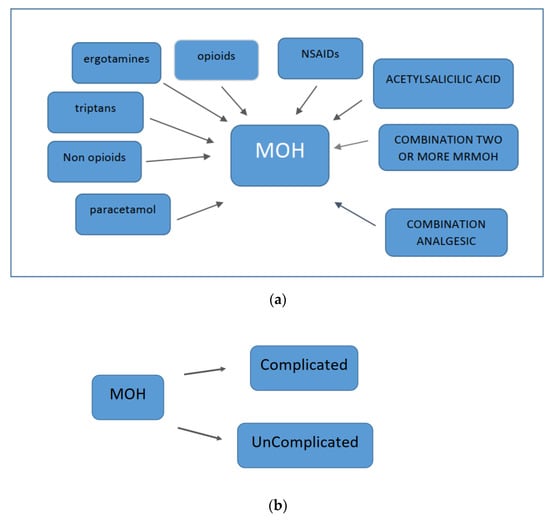

4. Type of Excessively Used Therapy

Excessive use of any type of analgesic therapy can lead to the development of medication-overuse headaches (MOHs) (Figure 2). Excessive use of triptans leads to a more rapid development of MOH compared to other analgesic therapies [66]. There is research evidence that suggests both triptans and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can lead to MOH only when the frequency of previous headaches is increased. In fact, NSAIDs may have a preventive effect on patients who have fewer than 10 headache days per month and may prevent the chronicity of headaches [66,67]. Opioids and barbiturates increase headache chronification and the development of refractory headaches compared with triptans and NSAIDs [68]. Excessive medication use can lead not only to the worsening of headaches but also to other health problems. Chronic use of NSAIDs can lead to cardiovascular, renal, and gastrointestinal problems. Excessive use of acetaminophen can lead to liver damage. Opioids have sedative properties and may lead to the development of a withdrawal syndrome with the occurrence of autonomic phenomena upon sudden discontinuation of excessive medication. Barbiturates can cause epileptic seizures when excessive medication is suddenly discontinued. Excessive medication with benzodiazepines can lead to sedation and cognitive problems. For these reasons, gradual discontinuation of these agents is recommended. Signs of ergotism and peripheral arterial insufficiency [69] may occur in patients taking excessive ergotamine. MOH has several subtypes, depending on the type of medication taken excessively. All these data are summarized in Figure 1.

5. Psychosocial Factors

The presence of psychiatric comorbidities, certain personality traits, and socioeconomic status are considered important factors in the development of medication-overuse headaches (MOHs). Anxiety and depression are common in MOH patients compared to patients with episodic headaches and represent a risk factor for the development of MOH [70,71,72]. Anxiety, depression, stress, and a tendency toward a ruminative thinking style are present in MOH patients [73,74,75]. Psychological studies of MOH patients have shown that they often have difficulty controlling their emotions and behavior [70]. Obsessive-compulsive personality traits are common in MOH patients, while some MOH patients also exhibit addictive behavior [76,77]. MOH patients have been shown to be highly dependent on excessive medication use [78]. The presence of addictive behavior is a predictor of poor prognosis and poor treatment outcomes in MOH [79,80]. Introversion, decreased social activity, perfectionism, and dysphoric features are common findings in MOH patients [78,81]. High levels of psychological distress associated with poor lifestyle habits (smoking, physical inactivity, obesity) may be associated with the development of MOH [82]. Depression, anxiety, paranoia, and personality disorders may negatively impact the process of medication overuse cessation and treatment outcomes in MOH [83,84]. Socioeconomic factors are important for treatment outcome and the frequency of relapse in MOH. Unemployment, smoking, regular alcohol use, low socioeconomic status, immigration, and loneliness have a negative impact on MOH treatment outcomes [85,86].

6. Impact of Medication-Overuse Headache (MOH)

As mentioned previously, medication-overuse headache (MOH) has a significant negative impact on the daily and social activities and quality of life of affected individuals [87,88]. Studies analyzing differences between MOH patients have shown that these negative effects vary. In the COMOESTAS study, MOH patients who overused triptans and ergotamines had a lower score on the MIDAS questionnaire (fewer negative effects of headache) compared to MOH patients who overused opioids or multiple types of analgesics. In addition, this study showed that patients who overused triptans had fewer psychiatric comorbidities (depression, anxiety) [89]. It was observed that migraine patients with other pain syndromes, significant dysfunction, and activity limitations were more likely to overuse analgesics [90]. These findings improved the value of a multidisciplinary approach to MOH patients. Some patients overuse analgesic therapy out of fear of the negative consequences of the headache they have been suffering from for some time [91,92]. It has been shown that patients who continuously use excessive analgesic medication have a slightly better quality of life compared to those whose excessive medication is abruptly discontinued. This is interpreted as a direct effect of the excessive medication itself and suggests that the process of discontinuing the excessive medication may also have a negative effect on the patient [93].

MOH can be uncomplicated (type 1) or complicated (type 2) [94] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Types of MOH: (a) type 1 and (b) type 2.

An important factor that influences the complexity of CGRP-related disorders (CRDs) is the duration of the disease (>1 year), the presence of relapses, and previous unsuccessful attempts at therapeutic management [95]. Interpersonal differences between patients with CRDs in terms of clinical complexity and patient impact suggest possible different pathophysiological processes in different patients.

7. Comorbidities

Recognizing comorbidities in migraine patients is important to study their relationship, causality, shared etiology, pathogenesis, and other aspects. Psychiatric comorbidities are common, especially anxiety and depression [89,95]. In the COMOESTAS study, 40% of migraine patients met criteria for depression and 27.7% met criteria for anxiety [96]. In the EUROLIGHT cross-sectional study conducted in 10 countries of the European Union, similar results were obtained, with a greater difference in the frequency of these comorbidities compared to the group with migraine without excessive use of analgesics [97]. The SAMOHA study examined the frequency of psychopathologic comorbidities in migraine patients compared to patients with episodic migraine and healthy controls [98]. The frequency of moderate to severe anxiety was higher in both groups with headaches, whereas the frequency of addictive disorders was significantly higher in patients with migraine. Patients with migraines often had multiple psychiatric comorbidities. Obsessive-compulsive syndrome has been shown to be associated with migraine [99]. One-third of migraine patients may have subclinical forms of obsessive-compulsive syndrome, which is a recognized risk factor for the chronicity of migraine [100,101]. Migraine may be associated with behavioral disorders related to substance use [72,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112]. Although similar neurobiological mechanisms are hypothesized for these two entities, it has been shown that there are distinct personality traits in patients with migraine and those with addiction syndromes [113,114]. Obesity is a risk factor for the chronicity of migraine, although there are studies that have questioned this association [114]. An association has been demonstrated between obesity, physical inactivity, smoking, and the occurrence of migraine [97]. The association between obesity and migraine has also been observed in children [115]. Patients with migraines are more likely to have sleep disturbances [116].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/brainsci13101408

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!