Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Architecture And Design

The greenery-covered tall building, an innovative building typology that substantially integrates vegetation into the design, promises to transform urban landscapes into more sustainable and livable spaces.

- high-rise buildings

- vegetation

- advantages

- disadvantages

- biophilic design

- sustainability

1. The Increasing Demand for Nature

People demand reconnecting with nature for multiple reasons, including massive urbanization, health problems, energy crises, artificial digital proliferation and increases in screen time, climate change and resilience, environmental and air quality degradation, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, and poor aesthetics and urban design. Densely populated cities are often characterized by high stress levels and noise pollution from traffic, construction, and other urban activities. Prolonged exposure to constant noise can lead to irritability and difficulty in relaxation and concentration. The constant presence of large crowds and congestion in urban areas can create a sense of claustrophobia and anxiety. Busy streets crowded public transportation, and packed public places can contribute to feeling overwhelmed [1,2,3,4,5,6].

Long periods of electronic device use have further increased the demand for reconnecting with nature. As modern life progressively revolves around electronic devices, such as smartphones, computers, and tablets, finding ways to disconnect from the digital world and reconnect with the natural world has become essential. Nature provides a respite from the constant stimuli of electronic devices and offers an opportunity to relax, unwind, and refresh mentally and physically. Outdoor activities like strolling through a park or relaxing in a green area can aid in lowering stress levels, elevate mood, and advance general well-being. Nature’s calming effects can counteract the potential negative impacts of prolonged screen time and electronic device use [7,8].

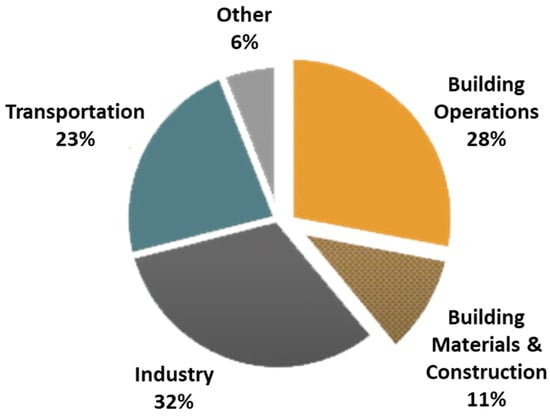

Urban areas are often plagued by poor air quality, increasing the demand to integrate nature into urban living. The concentration of human activities, industries, transportation, and construction in urban settings leads to the emission of pollutants that can negatively impact air quality. Manufacturing plants and industrial facilities in urban areas release various pollutants into the atmosphere, including sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon dioxide (CO2), and other hazardous substances. Poor air quality can harm public health, leading to respiratory, cardiovascular, and other health complications. Buildings are significant sources of CO2 emissions in urban environments (Figure 1). The energy used for lighting, cooling, heating, and operating appliances in residential, commercial, and institutional buildings often relies heavily on fossil fuels. The combustion of these fossil fuels, such as coal, natural gas, and oil, contributes to the greenhouse effect and climate change by releasing CO2 into the atmosphere [9].

Figure 1. Global CO2 Emissions by Sector. (Graph by author, adapted from [9]).

Recently, COVID-19 further emphasized the importance of cleaner air for public health and the need to reintegrate nature into cities. As a respiratory disease, COVID-19 has underscored the critical role of clean air in maintaining public health and well-being. Poor air quality, often prevalent in urban areas due to pollution, can exacerbate respiratory issues and weaken the immune system, making individuals more vulnerable to respiratory infections. This realization has prompted cities to reevaluate their urban planning and environmental policies, focusing on creating greener and more sustainable living spaces. The importance of reintegrating nature into cities has become evident during the pandemic [10,11].

Overall, the growing demand for reconnecting with nature stems from a recognition of the many benefits that nature offers in improving physical and mental health, promoting sustainability, and creating more pleasant and resilient urban environments. As cities face numerous challenges in the 21st century, integrating nature into the urban landscape has become a key priority for creating healthier, happier, and more sustainable places to live.

2. Biophilic Design

Biophilic design is a concept that recognizes the inherent human need to connect with nature and seeks to bridge the gap between the built environment and the natural world. By incorporating elements of nature into architectural and interior design, biophilic design aims to create spaces that evoke positive emotional responses and enhance the well-being of occupants. Integrating vegetation, plants, and greenery into buildings can profoundly impact the occupants’ mental and physical health. Exposure to natural elements such as plants and natural light has been shown to reduce stress levels, improve mood, and increase productivity. Greenery and living plants in indoor spaces can also improve indoor air quality, as they absorb pollutants and release oxygen, creating a healthier and more pleasant indoor environment. Using natural sounds, such as running water or birdsong, and scents, such as the aroma of fresh flowers or wood, can also contribute to a more immersive and sensory experience, further strengthening the connection to nature.

Incorporating natural materials, such as wood and stone, can evoke a sense of grounding and connection to the natural world, promoting feelings of warmth and comfort. Additionally, incorporating natural patterns and textures into the design can create a sense of harmony and balance, further enhancing the overall experience of the space. Biophilic design seeks to create spaces that provide functional utility and evoke a sense of well-being, tranquility, and connection to the natural world. By integrating natural elements and processes into the built environment, biophilic design offers an innovative and holistic approach to designing spaces that promote human health and resilience in the face of modern urban challenges [12,13,14,15].

3. Vertical Landscaping and Planting

Cities are getting denser, leaving little space for “horizontal” landscaping and planting. Consequently, architects have had to get creative in using the vertical plane for planting. They believe vertical green spaces can act as natural air purifiers, absorbing pollutants and improving air quality, making cities more resilient to public health crises. As such, they diligently explore vertical gardening, making lush vegetation and trees grow on the upper floors, terraces, balconies, walls, and roofs. They have been designing new projects that bring nature and gardens, usually found on the ground level, onto the high-rise building, allowing users to reconnect with nature and create natural environments in the sky [16,17].

Politicians may back up these projects for their merits. Increasingly, cities oppose all-glass skyscrapers because of their environmental harm. For example, Bill de Blasio, former New York City Mayor (from 2014 to 2021), has proposed a bill to ban all-glass skyscrapers to decrease NYC’s greenhouse emissions by 30 percent [18]. According to de Blasio, all-glass towers are “incredibly inefficient” since so much energy escapes through the glass—they are the city’s primary source of greenhouse gas emissions. Toronto, Canada, has been encouraging using timber framing—highly compressed wood, called cross-laminated timber wood, which is extremely strong—in constructing high-rise buildings [19,20]. Utrecht, the Netherlands, has required all buildings to have green or solar roofs [21]. In Singapore, the government supports structures that integrate greenery by covering up to half the cost. As a result, nearly all new buildings in Singapore are rich in vegetation. Many European cities are witnessing the proliferation of vertical greenery features such as living walls, vegetated terraces, and green roofs.

Italian architect Stefano Boeri invented the “vertical forest” concept, which involves constructing high-rise buildings extensively covered with trees and plants on various floors, creating a vertical ecosystem within urban environments. The core idea of the vertical forest is to bring nature back into urban centers by integrating lush greenery into tall buildings. Boeri demonstrated his concept in Milan, Italy, and “replicated” the model in different projects, including Trudo Vertical Forest in Eindhoven, the Netherlands; Easyhome Huanggang Vertical Forest City Complex in Huanggang, Hubei Province, China; and Nanjing Vertical Forest in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China. He has also proposed the same model for cities like Dubai [22].

Further, Boeri has proposed giant visions based on his original “vertical forest” model in Milan. He has suggested Liuzhou Forest metropolis as a model for a Chinese metropolis of around 1.5 million inhabitants in the hilly southern region of Guangxi, one of the most smog-affected urban areas in the world due to excessive industrialization and overpopulation. The concept depicts an urban composition along the Liujiang River that spans an area of 175 hectares and includes buildings such as offices, houses, hotels, hospitals, and schools that are almost totally contained by plants and trees of varying species and sizes. About 40,000 trees and one million plants representing over one hundred species will call the Liuzhou Forest City home. By integrating extensive trees and plants, Boeri’s project aims to sequester significant quantities of carbon dioxide (CO2) and microparticles while concurrently generating substantial amounts of oxygen to mitigate the detrimental effects of severe air pollution [23].

STH BNK by Beulah is a groundbreaking architectural project in Melbourne, Australia, that aims to become the world’s first-ever supertall vertical garden. The development comprises two twisting towers, one rising to 366 m and the other to 288 m, connected by a sky bridge. These towers will be situated above the Yarra River and will house a mix of residential, commercial, and retail spaces, a wellness hub, and a vertical school. With over five and a half kilometers of vertical gardens and sky parks extending as high as 365 m above street level, the project aspires to set a new standard for sustainable and green urban development. The towers’ various levels will feature dramatic planting, with greenery adorning the building’s façades, terraces, and sky parks. This extensive use of vegetation enhances the aesthetic appeal and contributes to environmental benefits like air purification and temperature regulation. The STH BNK project is designed by UN Studio and Cox Architecture, renowned architectural firms known for their innovative and sustainable design solutions. Construction has already commenced, and the project is expected to be completed by 2028 [24].

4. Controversy

As integrating greenery into tall buildings becomes a growing trend, growing controversy arises concerning this new building typology. The proponents of this architectural design approach claim the greenery-covered tower model offers multiple benefits, including improving the health of people and the environment and mitigating climate change challenges. Greenery-covered tall buildings have many benefits, such as purifying the air, reducing ambient temperature and noise, reducing stress, boosting productivity, and a longer residence time. Green coverings can significantly reduce other air pollutants, including soot and dust [25,26,27].

A growing concern is that this could be a new “greenwashing” propaganda. Architects are taking advantage of the positive public perception of plants and trees and their many health and environmental benefits by integrating trees and plants into a proposed building to “sell” their designs. However, adding plants and trees to tall buildings poses several challenges that the public (and even some professionals and scholars) may not be aware of [28]. Due to the additional structural requirements, irrigation systems, and specialized planting techniques required to support the weight of the vegetation, creating green spaces in tall buildings can be costly. Green areas in tall buildings require routine and specialized maintenance to ensure the health and vitality of the plants. This consists of pruning, watering, pest control, and monitoring for prospective problems. Incorporating vegetation into structures necessitates compliance with fire and building codes, which may have specific requirements for fire resistance, egress routes, and safety measures. Green spaces within towering buildings may affect the space’s functionality. For instance, windows and views may be obstructed, and interior floor plans may need to be modified to accommodate the natural elements. Maintaining green spaces in lofty buildings frequently necessitates centralized management and control to ensure uniform care and a consistent appearance. This can inhibit the organic and spontaneous growth typically observed in natural environments [29,30].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/buildings13092362

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!