Dealing with students’ maladaptive behaviour in the classroom, such as verbal aggressive behaviour, is challenging, particularly for novice teachers. They often encounter limited opportunities for training and practice in handling such incidents during their pre-service education, rendering them ill-equipped and uncertain when confronted with instances of verbal aggression during their initial teaching experiences. Although reacting appropriately to students’ verbal aggressive behaviour is crucial, teacher education programs seem to appear inadequate in preparing preservice teachers to manage students’ maladaptive behaviour effectively. The authors therefore developed a comprehensive competence model consisting of concrete steps to be taken during or immediately following an incident and overarching attitudes to be adopted throughout the incident managing process.

- verbal aggression management

- competence development

- classroom management

1. Aggression in the Classroom

2. Teachers’ Role in Aggression-Related Classroom Management

3. Competence Development

4. Verbal Aggression Management Competence Model

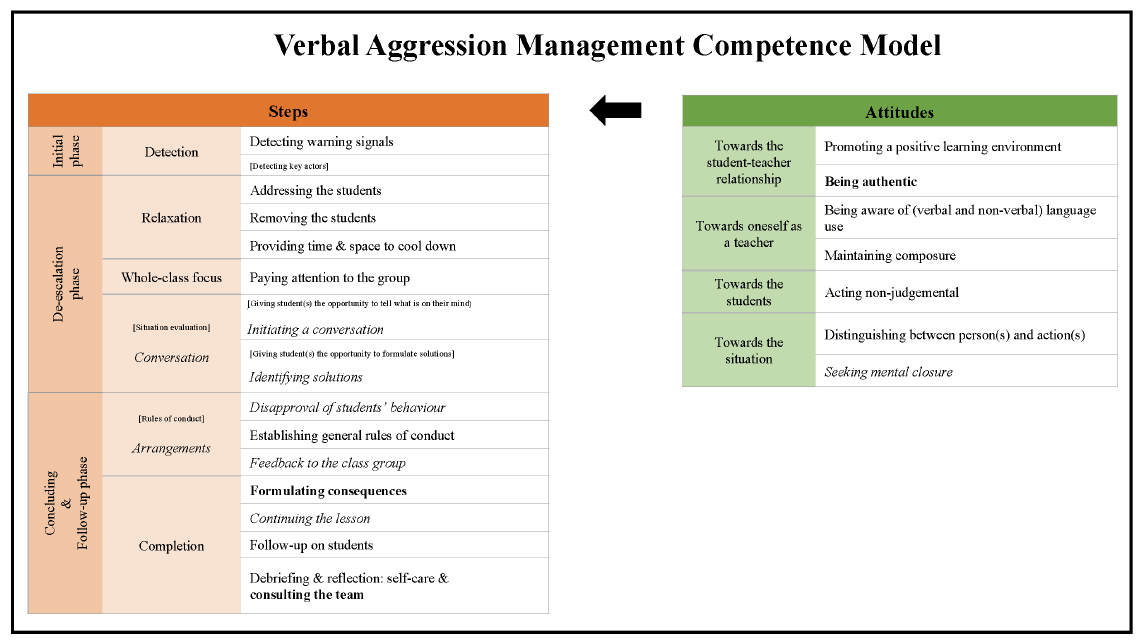

The authors therefore developed a coherent and grounded ‘Verbal Aggression Management Competence’ model based on literature covering several domains and validation interviews with educational experts. The final model consists of steps that can be taken during and immediately after an incident of VAB and teacher attitudes during such incidents. These attitudes influence day-to-day educational practices but play a specific role in addressing students’ VAB.

The steps of the V-AMC model were developed with social-cognitive problem-solving models in mind, containing a three-phased classification: the initial phase (containing step 1), the de-escalation phase (containing steps 2 to 4), and the follow-up phase (containing steps 5 to 7). Besides steps, the V-AMC model also addresses teachers’ attitudes. Considered transversal, these attitudes act on each step of the competence model. This study contributes a structured framework to empower novice teachers, offering tools to address verbal aggressive behaviour within the classroom environment. Furthermore, it highlights the potential of incorporating this model into teacher education programs, facilitating the competence development of future teachers, and fostering conducive learning environments.

The steps of the V-AMC model were developed with social-cognitive problem-solving models in mind, containing a three-phased classification: the initial phase (containing step 1), the de-escalation phase (containing steps 2 to 4), and the follow-up phase (containing steps 5 to 7). Besides steps, the V-AMC model also addresses teachers’ attitudes. Considered transversal, these attitudes act on each step of the competence model. This study contributes a structured framework to empower novice teachers, offering tools to address verbal aggressive behaviour within the classroom environment. Furthermore, it highlights the potential of incorporating this model into teacher education programs, facilitating the competence development of future teachers, and fostering conducive learning environments.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/educsci13100971

References

- Guerra, N.G.; Huesmann, L.R.; A Cognitive-Ecological Model of Aggression. Rev. Int. Psychol. Soc. 2004, 17, 177–204, .

- McCall, G.S.; Shields, N.; Examining the Evidence from Small-Scale Societies and Early Prehistory and Implications for Modern Theories of Aggression and Violence. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2008, 13, 1-9, .

- Spielfogel, J.E.; McMillen, J.C.; Current Use of De-Escalation Strategies: Similarities and Differences in de-Escalation across Professions. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2017, 15, 232-248, .

- Coie, J.D.; Dodge, K.A.. Aggression and Antisocial Behavior. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development; Coie, J.D.; Dodge, K.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA,, 1998; pp. 779–862.

- Krahé, B.. The Social Psychology of Aggression; Krahé, B., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. ISBN 978-0-203-08217-1.

- Allen, J.J.; Anderson, C.A.. Aggression and Violence: Definitions and Distinctions. In The Wiley Handbook of Violence and Aggression; Allen, J.J.; Anderson, C.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2017, 2017; pp. 1–14.

- Dishion, T.J.; Patterson, G.R.. The Development and Ecology of Antisocial Behavior in Children and Adolescents. In Developmental Psychopathology; Cicchetti, D., Cohen, D.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 503–541.

- Anderson, C.; Huesmann, L. . Human Aggression: A Social-Cognitive View; Anderson, C.; Huesmann, L. , Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2003; pp. 416 p..

- Donoghue, C.; Raia-Hawrylak, A.; Moving beyond the Emphasis on Bullying: A Generalized Approach to Peer Aggression in High School. Child. Sch. 2016, 38, 30-39, .

- Infante, D.A.; Wigley, C.J.; Verbal Aggressiveness: An Interpersonal Model and Measure. Commun. Monogr. 1986, 53, 61–69, .

- Taylor, G.G.; Smith, S.W.; Teacher Reports of Verbal Aggression in School Settings Among Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2019, 27, 52–64, .

- Poling, D.V.; Smith, S.W.; Taylor, G.G.; Worth, M.R.; Direct Verbal Aggression in School Settings: A Review of the Literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 46, 127–139, .

- Kaplan, S.G.; Wheeler, E.G.; Survival Skills for Working with Potentially Violent Clients.. Soc. Casework Soc. Casework, 64, 339-346, .

- Landrum, T.; Kauffman, J. . Behavioral Approaches to Classroom Management. In Handbook of Classroommanagement: Research, Practice, and Contemporary Issues; Landrum, T.; Kauffman, J. , Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 47–71.

- Paterson, B.; Leadbetter, D.. De-Escalation in the Management of Aggression and Violence: Towards Evidence-Based Practice. In Aggression and Violence; Turnbull, J., Paterson, B., Eds.; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 1999; pp. 95–123.

- Maier, G.J.; Managing Threatening Behavior: The Role of Talk Down and Talk Up. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 1996, 34, 25-30, .

- Albert, D.; Chein, J.; Steinberg, L.; The Teenage Brain: Peer Influences on Adolescent Decision Making. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 114–120, .

- van den Berg, G.J.; Lundborg, P.; Nystedt, P.; Rooth, D.-O.; Critical Periods During Childhood and Adolescence. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2014, 12, 1521–1557, .

- Salmela-Aro, K.. Stages of Adolescence; Brown,B. Bradford; Prinstein; Mitchell J. , Eds.; Academic press: Cambridge, US, 2011; pp. 360-368.

- Coyne, S.M.; Archer, J.; Eslea, M.; “We’re Not Friends Anymore! Unless…”: The Frequency and Harmfulness of Indirect, Relational, and Social Aggression. Aggr. Behav. 2006, 32, 294–307, .

- Goldweber, A.; Waasdorp, T.E.; Bradshaw, C.P.; Examining the Link between Forms of Bullying Behaviors and Perceptions of Safety and Belonging among Secondary School Students. J. Sch. Psychol. 2013, 51, 469-485, .

- Prinstein, M.J.; Cillessen, A.H.; Forms and Functions of Adolescent Peer Aggression Associated With High Levels of Peer Status. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2003, 49, 310-342, .

- Jung, J.; Krahé, B.; Bondü, R.; Esser, G.; Wyschkon, A.; Dynamic Progression of Antisocial Behavior in Childhood and Adolescence: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study from Germany. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2018, 22, 74-88, .

- Espelage, D.L.; Ecological Theory: Preventing Youth Bullying, Aggression, and Victimization. Theory Pract. 2014, 53, 257-264, .

- Huesmann, L.R.; An Integrative Theoretical Understanding of Aggression: A Brief Exposition. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 19, 119-124, .

- Espelage, D.; Bullying Prevention: A Research Dialogue with Dorothy Espelage. Prev. Res. 2012, 19, 17-19, .

- Boxer, P.; Goldstein, S.E.; Musher-Eizenman, D.; Dubow, E.F.; Heretick, D.; Developmental Issues in School-Based Aggression Prevention from a Social-Cognitive Perspective. J. Prim. Prev. 2005, 26, 383-400, .

- Orpinas, P.; Horne, A.M.; A Teacher-Focused Approach to Prevent and Reduce Students’ Aggressive Behavior. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 26, 29-38, .

- Fossum, S.; Handegård, B.H.; Martinussen, M.; Mørch, W.T.; Psychosocial Interventions for Disruptive and Aggressive Behaviour in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 17, 438-451, .

- Yeager, D.S.; Trzesniewski, K.H.; Dweck, C.S.; An Implicit Theories of Personality Intervention Reduces Adolescent Aggression in Response to Victimization and Exclusion. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 970-988, .

- Wilson, S.J.; Lipsey, M.W.; Derzon, J.H.; The Effects of School-Based Intervention Programs on Aggressive Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 1, .

- Oostdam, R.J.; Koerhuis, M.J.C.; Fukkink, R.G.; Maladaptive Behavior in Relation to the Basic Psychological Needs of Students in Secondary Education. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 34, 601-619, .

- Troop-Gordon, W.; Ladd, G.W.; Teachers’ Victimization-Related Beliefs and Strategies: Associations with Students’ Aggressive Behavior and Peer Victimization. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 43, 45-60, .

- Troop-Gordon, W.; The Role of the Classroom Teacher in the Lives of Children Victimized by Peers. Child Dev. Perspec 2015, 9, 55-60, .

- Page, A.; Jones, M.; Rethinking Teacher Education for Classroom Behaviour Management: Investigation of an Alternative Model Using an Online Professional Experience in an Australian University. Aust. J. Teach. Educ 2018, 43, 84-104, .

- Marzano, R.J.; Marzano, J.S.; Pickering, D.J.. Classroom Management That Works: Research-Based Strategies for Every Teacher; Marzano, R.J.; Marzano, J.S.; Pickering, D.J., Eds.; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2003; pp. ISBN 0-87120-793-1.

- Simonsen, B.; Fairbanks, S.; Briesch, A.; Myers, D.; Sugai, G.; Evidence-Based Practices in Classroom Management: Considerations for Research to Practice. Educ. Treat. Child. 2008, 31, 351-380, .

- Glock, S.; Kleen, H.; Teachers’ Responses to Student Misbehavior: The Role of Expertise. Teach. Educ. 2019, 30, 52-68, .

- Vaaland, G.S.; Back on Track: Approaches to Managing Highly Disruptive School Classes. Cogent Educ. 2017, 4, 1396656, .

- Barnes, T.N.; Smith, S.W.; Miller, M.D.; School-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions in the Treatment of Aggression in the United States: A Meta-Analysis.. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2014, 19, 311-321, .

- Romi, S.; Lewis, R.; Roache, J.; Riley, P.; The Impact of Teachers’ Aggressive Management Techniques on Students’ Attitudes to Schoolwork. J. Educ. Res. 2011, 104, 231-240, .

- Tummers, L.; Brunetto, Y.; Teo, S.T.T.; Workplace Aggression: Introduction to the Special Issue and Future Research Directions for Scholars. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2016, 29, 2-10, .

- Price, O.; Baker, J.; Key Components of De-Escalation Techniques: A Thematic Synthesis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 21, 310-319, .

- Richmond, J.; Berlin, J.; Fishkind, A.; et al.; Verbal De-Escalation of the Agitated Patient: Consensus Statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA De-Escalation Workgroup. WestJEM 2012, 13, 17-25, .

- Berring, L.L.; Pedersen, L.; Buus, N.; Coping with Violence in Mental Health Care Settings: Patient and Staff Member Perspectives on De-Escalation Practices. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs 2016, 30, 499-507, .

- Engel, R.S.; McManus, H.D.; Herold, T.D; Does De-escalation Training Work?: A Systematic Review and Call for Evidence in Police Use-of-force Reform. Criminol. Public Policy 2020, 19, 721-759, .

- Hallett, N.; Dickens, G.L.; De-Escalation of Aggressive Behaviour in Healthcare Settings: Concept Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud 2017, 75, 10-20, .

- Spencer, S.; Johnson, P.; Smith, I.C.; De-Escalation Techniques for Managing Non-Psychosis Induced Aggression in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, /, CD012034, .

- Milczarek, M.. Workplace violence and harassment: a European picture; Publications Office of the European Union, Eds.; EU-OSHA: Bilboa, Spain, 2010; pp. /.

- LeBlanc, M.M.; Barling, J.; Workplace Aggression. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci 2004, 13, 9-12, .

- Troop-Gordon, W.; Kaeppler, A.K.; Corbitt-Hall, D.J.; Youth’s Expectations for Their Teacher’s Handling of Peer Victimization and Their Socioemotional Development. J. Early Adolesc. 2021, 41, 13-42, .

- Wolff, C.E.; van den Bogert, N.; Jarodzka, H.; Boshuizen, H.P.A; Keeping an Eye on Learning: Differences Between Expert and Novice Teachers’ Representations of Classroom Management Events. J. Teach. Educ 2015, 66, 68–85, .

- Sipman, G.; Martens, R.; Thölke, J.; McKenney, S.; Exploring Teacher Awareness of Intuition and How It Affects Classroom Practices: Conceptual and Pragmatic Dimensions. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2021, , , .

- Vanlommel, K.; Van Gasse, R.; Vanhoof, J.; Van Petegem, P.; Teachers’ Decision-Making: Data Based or Intuition Driven?. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 83, 75–83, .

- Dicke, T.; Elling, J.; Schmeck, A.; Leutner, D.; Reducing Reality Shock: The Effects of Classroom Management Skills Training on Beginning Teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 48, 1-12, .

- Paramita, P.; Anderson, A.; Sharma, U.; Effective Teacher Professional Learning on Classroom Behaviour Management: A Review of Literature. Aust. J. Teach. Educ 2020, 45, 61–81, .

- Barth, V.L.; Piwowar, V.; Kumschick, I.R.; Ophardt, D.; Thiel, F.; The Impact of Direct Instruction in a Problem-Based Learning Setting. Effects of a Video-Based Training Program to Foster Preservice Teachers’ Professional Vision of Critical Incidents in the Classroom. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 95, 1-12, .

- Bergsmann, E.; Schultes, M.-T.; Winter, P.; Schober, B.; Spiel, C.; Evaluation of Competence-Based Teaching in Higher Education: From Theory to Practice. Eval. Program Plan 2015, 52, 1–9, .

- Breakwell, G.M.. Coping with Aggressive Behaviour; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. /.

- Subban, P.K.; Round, P.; Differentiated Instruction at Work. Reinforcing the Art of Classroom Observation through the Creation of a Checklist for Beginning and Pre-Service Teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 40, 7, .

- Shavelson, R.J.; On the Measurement of Competency. Empir. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2010, 2, 41-63, .

- Blömeke, S.; Gustafsson, J.-E.; Shavelson, R.J.; Beyond Dichotomies: Competence Viewed as a Continuum. Z. Psychol. 2015, 223, 3-13, .

- Billett, S.; Subjectivity, Learning and Work: Sources and Legacies. Vocat. Learn. 2008, 1, 149-171, .

- Ormrod, J.E.. Human Learning; Pearson Education: Cranbury, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. /.

- Sternberg, R.J.; Ben-Zeev, T.. Complex Cognition: The Psychology of Human Thought; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. ISBN 0-19-510771-3.

- Huesmann, L.R.. The Role of Social Information Processing and Cognitive Schema in the Acquisition and Maintenance of Habitual Aggressive Behavior. In Human Aggression; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 73-109.

- Kaiser, G.; Busse, A.; Hoth, J.; König, J.; Blömeke, S.; About the Complexities of Video-Based Assessments: Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to Overcoming Shortcomings of Research on Teachers’ Competence. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2015, 13, 369–387, .

- Berliner, D.C; Learning about and Learning from Expert Teachers. Int. J. Educ. Res 2001, 35, 463–482, .

- van Es, E.A.; Sherin, M.G.; Learning to Notice: Scaffolding New Teachers’ Interpretations of Classroom Interactions. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2002, 10, 571–596, .

- Gegenfurtner, A.; Lewalter, D.; Lehtinen, E.; Schmidt, M.; Gruber, H; Teacher Expertise and Professional Vision: Examining Knowledge-Based Reasoning of Pre-Service Teachers, In-Service Teachers, and School Principals. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 59, .

- Carmien, S.; Kollar, I.; Fischer, G.; Fischer, F. . The Interplay of Internal and External Scripts: A Distributed Cognition Perspective. In Scripting Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning; Fischer, F., Kollar, I., Mandl, H., Haake, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 303–326.

- Wolff, C.E.; Jarodzka, H.; Boshuizen, H.P.A; Classroom Management Scripts: A Theoretical Model Contrasting Expert and Novice Teachers’ Knowledge and Awareness of Classroom Events. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 131–148, .

- Bowman, B.; Whitehead, K.A.; Raymond, G.; Situational Factors and Mechanisms in Pathways to Violence. Psychol. Violence 2018, 8, 287–292, .