Metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC) represents an oncological emergency and clinicians should be aware of the potential long-term neurological impact. Urgent diagnosis and treatment is still challenging. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the whole spine is the imaging method of choice that should be carried out within 24 h of clinical suspicion. Steroid therapy is administered immediately after the establishment of diagnosis, followed by definitive treatment, which may include any combination of surgery and/or radiotherapy (RT). Treatment should ideally be initiated within 24 h of the confirmed MSCC. Trainees require further teaching to improve their knowledge. Equally, oncological patients should be aware of the signs and symptoms of MSCC in order to optimise early detection.

MSCC remains a challenging oncological emergency and requires effective multidisciplinary management for optimal effects on patients’ morbidity and quality of life. Diagnosis and prompt treatment can be difficult due to patient, clinician, and institutional factors. MSCC can present with a range of symptoms from minor sensory, motor, or autonomic disturbances to severe pain and complete paraplegia.

MSCC is a complication of cancer that occurs in 5–10% of patients and can particularly complicate the final stages of their disease. However, it could also be the presenting symptom of a malignancy; in a retrospective cohort study, 21% of patients with MSCC had no diagnosis of cancer within the last year. The exact incidence of cases in England and Wales is not clarified, as cases are not systematically recorded.

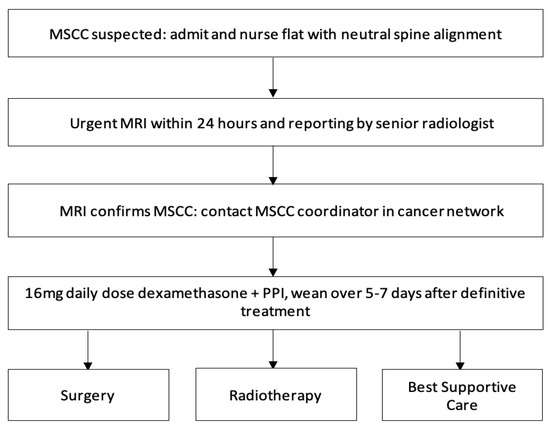

Studies have established that the mobility of patients at the time of diagnosis is a significant prognostic factor of mobility after MSCC treatment. Therefore, to avoid serious neurological implications of MSCC, it is crucial that diagnosis is made as early as possible. Patients should have rapid access to MRI, appropriate surgery, and RT, under an MSCC coordinator. Once the diagnosis of MSCC is suspected, patients with neurological deficits should receive prompt administration of dexamethasone. Local management strategies generally include palliative RT, or surgical posterior decompression with or without instrumentation or total en bloc spondylectomy.

Diagnosing and treating MSCC as an oncological emergency remains critical to preserving neurological function, quality of life, and survival for our patients. For earlier diagnosis, medical knowledge and understanding of the symptoms and signs of MSCC are essential. Back pain is commonly the first symptom of MSCC and occurs in up to 95% of patients; it can begin two to four months before progression of other neurological symptoms. The pain, either localised or radicular, usually increases in severity over time and can be worsened on coughing or lying down due to increased pressure and distension of the epidural plexus. MSCC should be considered in patients with cancer that have severe unremitting or nocturnal pain in the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar spine. There is a lack of awareness of the pain in early stages of MSCC in primary and secondary care. This is due to cancer patients having a different significance and type of pain compared to pain in non-cancer patients—for example, their pain could be attributed to tumour progression.

Optimising education for doctors in A&E departments would be vital to improving our speed in detecting MSCC within 24 h. Furthermore, there is a delay in referring to the acute oncology services. Many patients are referred once an MRI confirms MSCC. It is crucial the referral to an MSCC coordinator within 24 h. Increased education of the management of MSCC and the role of acute oncology service in the A&E departments and acute medical teams may encourage earlier referral and a lower threshold for investigations leading to earlier diagnosis and treatment. Increased education for doctors on these issues is also well recommended in the literature.

Other symptoms of MSCC can be divided into motor, sensory, and autonomic deficits. Limb weakness can be the second most common symptom of MSCC as it affects 60–85% of patients. Patients report a progressive change in their gait or weakness over days or weeks, which can be difficult to appreciate if regular clinical reviews are not undertaken. This neurological change is considered an emergency for patients and doctors compared to other preceding symptoms, which further implicates diagnostic and treatment delay. Similarly, symptoms which can indicate a late consequence of MSCC are perineal anaesthesia in a saddle distribution and bladder and bowel dysfunction—this could be urinary retention, urinary or faecal incontinence, and constipation. Sensory symptoms are less common but patients may report paraesthesia extending up to 5 dermatomes below the level of compression.

-

Timely access to MRI imaging will also improve diagnostic delays of MSCC. MRI remains the gold-standard to diagnosing MSCC with sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 97% and should be done within 24 h. Despite the non-invasive and highly effective investigation choice of MRI, many patients are still being diagnosed late with this.

As well as early diagnosis, treatment of MSCC should be delivered within 24 h. The treatment is a combination of high-dose steroids, RT, surgical intervention, and extensive rehabilitation, and must be initiated within 24 h of diagnosis to prevent further neurological decline . While awaiting definitive management, such as RT and surgery, high doses of steroids provide analgesia, decrease spinal cord vasogenic oedema, and the secondary complication of reduced arterial flow and therefore, prevent further neurological deterioration. In some cases, it can decompress the tumour causing the compression. Steroids should be given immediately within 12 h of diagnosis for optimum efficacy and weaned after RT or surgery over 5–7 days to avoid side-effects.

Surgery is indicated in patients for surgical decompression and spinal stabilisation. Surgical decompression followed by adjuvant RT has shown more favourable outcomes than RT alone in the literature. Patients should have a prognosis of more than six months to be considered for surgery. However, surgery can lead to complications such as pulmonary embolism, infections including postoperative pneumonia, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, and major bleeding. This may account for reluctance of neurosurgeons to operate.

RT is highly effective in MSCC by providing analgesia and preventing further neurological deterioration. It is indicated within 24 h of diagnosis and can provide benefit to patients who are not surgical candidates. Fractions of RT given depend on the primary malignancy and its systemic burden, duration of symptoms, and prognosis.

It is clear that a MSCC referral pathway needs to be more streamlined for improved treatment outcomes. Clinical oncologists should be included as part of the neurosurgical pathway recommended above in order to improve communication between three different areas of expertise and treatment timing. It may be advisable to have an MSCC coordinator in the oncology centre along with representatives from both the clinical oncologist and neurosurgical teams to oversee the treatment pathway and improve clinical practice. This could be further implemented in an MDM for MSCC mid-week compared to later on. Having an MSCC coordinator could improve both the diagnostic and treatment pathways. An MSCC coordinator could provide teaching to junior doctors on the referral process and treatment pathway as part of their core teaching curriculum. Furthermore, referral forms can be created, which include clinical history, assessment, MRI report, and contact details of the neurosurgical and clinical oncologist teams to encourage A&E and medical specialties to refer to them all simultaneously. This form can then be emailed to the MSCC coordinator who can act as the primary point of referral to these specialties. A defined pathway such as this will improve access to definitive treatment and consequently improve neurological outcomes.

MSCC represents an oncological emergency and clinicians should be aware of the potential long-term neurological impact. Urgent diagnosis and treatment is still challenging. MRI of the whole spine is the imaging method of choice that should be carried out within 24 h of clinical suspicion. Steroid therapy is administered immediately after the establishment of diagnosis, followed by definitive treatment, which may include any combination of surgery and/or RT. Treatment should ideally be initiated within 24 h of the confirmed MSCC. Trainees require further teaching to improve their knowledge. Equally, oncological patients should be aware of the signs and symptoms of MSCC in order to optimise early detection.