Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Sentinels are organisms whose characteristics (including health status) change due to acute or chronic effects in a given environment that can be evaluated (monitored) through serial surveillance.

- sentinels

- dogs

- cats

- environmental pollution

- indoor pollution

1. Introduction

Evidence that living beings can be natural sentinels of biological risks and environmental pollutants has been recognized for centuries [1]. In their book, Natterson-Horowitz and Bowers [2] point out that “In a world where no creature is truly isolated and disease spreads as fast as airplanes can fly, we are all canaries, and the entire planet it’s our coal mine”. Many birds, fish, wild and domesticated terrestrial mammals, and pets are valuable indicators of environmental pollution, displaying early warnings of exposure to a contaminated environment before humans are affected [3].

Sentinels are organisms whose characteristics (including health status) change due to acute or chronic effects in a given environment that can be evaluated (monitored) through serial surveillance [4,5,6,7]. Samples can be collected routinely, at random, or at predetermined intervals, and analyzed to identify potential health hazards to humans and other animals [4]. There are many criteria according to which a species should be considered a sentinel. In the first place, the sentinels must occupy a large area geographically close to human settlements and humans; their biology, sensitivity to pollutants, and bioaccumulation capacity have to be known [5]. They must have at least the same sensitivity to poisoning as humans, with similar physiology; their life span must be long enough to show the effects of not only the acute but of chronic exposures too, and the biological or clinical effects must develop early and be comparable to those in humans. The exposure pathway has to be similar to that of humans, which is feasible for companion animals sharing the same environment with their owners [4]. Among the phenotypic characteristics, the animals’ size is essential because of the sufficient amounts of tissue are needed for analysis, but other aspects, such as age or gender, must also be considered [6].

By testing and monitoring pets, we can detect early the presence and impact of pollutants for this information to be used to minimize the adverse effects on human health [7]. Thus, companion animals can literally be considered “sentinels” of environmental pollution [8].

The definition of sentinel organisms many times overlap with that of biomonitors, although the latter term may be considered broader. A biomonitor is an organism (or part of an organism or a community of organisms) that contains information on the quantitative aspects of the quality of the environment [9]. In this sense, sentinels are biomonitors too. Yet, active biomonitoring has a more intentional sense when, for example, biomonitors bred in laboratories are placed in a standardized manner in a certain environment to gather information. By contrast, especially when the term ‘natural sentinels’ is used, the organisms already present in the environment are monitored.

2. Pets as Sentinels for Environmental Pollution

2.1. Pets as Sentinels for Asbestos Fibers and Heavy Metals in the Environment

The usefulness of animals in the role of sentinels has been recognized more than a quarter-century ago. As the National Research Council of the United States devised [10] in 1991, the biologic effects of suspected toxic substances can be evaluated in animals kept in their natural habitat (including human homes) to assess the intensity of exposures, measure the effects of chemical mixtures, and determine the results of low-level exposures over a long period. Even more, observing the prevalence and incidence of certain pet pathologies reveal patterns that show the distribution of pollution in the area [11].

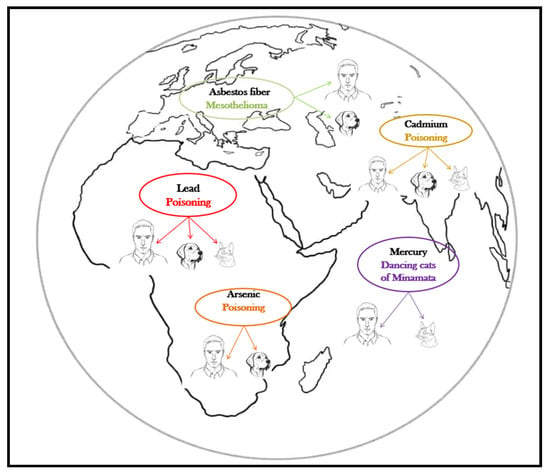

The harmful effects of metalloids and heavy metals are well described, and their association with specific diseases is as well, both in humans and companion animals (Table 1, Figure 2). The harmful health impact of these pollutants is similar, regardless the species exposed [12].

Figure 2. Pets, sentinels of environmental heavy metal/metalloid pollution.

Table 1. Human and small animal pathologies promoted by metalloid or heavy metal toxic exposure.

| Heavy Metal/Metalloid | Pets | Effects in Pets | References | Effects in Humans | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asbestos | Dogs | Canine malignant mesothelioma Pleural mesothelioma (more frequently than pericardial and peritoneal)—poor prognostic Pleural effusions, especially in old dogs, with males more prone than females |

[13] [14] [15] |

Human mesothelioma Pleural mesothelioma (more frequently pleural effusions) Peak incidence occurs in the 5th and 6th decades of life |

[16] [17] [18] |

| Chromium (Cr) | Dogs | Cardiac impairment, oxidative damage, altered ATP-aze content | [19] | Airway irritation, obstruction, and cancers Allergic dermatitis Dose dependent renal damage Gastrointestinal and hepatic impairment Hypoxic myocardiac changes Intravascular hemolysis |

[20] |

| Arsenic (As) | Dogs Cats |

Ulcerative dermatitis Myocarditis Bladder cancer Chronic renal failure |

[21] [22] |

Hyperpigmentation and keratosis Ischemic heart diseases Renal diseases Bladder cancer, skin, lungs, liver, kidney cancer Kidney damage |

[23] [24] [25] |

| Cadmium (Cd) | Dogs Cats |

Disrupted male reproduction Impaired pancreatic function Decreased bone-formation rate Chronic renal failure |

[26] [27] |

Altered male reproduction (hormonally and functionally) Disturbed calcium metabolism: osteopetrosis, osteomalaecia Itai-Itai disease (renal tubular dysfunction and osteomalaecia) Kidney failure |

[28] [29] [30] |

| Lead (Pb) | Dogs Cats |

Functional forebrain dysfunction and cortical blindness Anemia Epileptic seizures Bone sclerosis Chronic myocarditis chronic Renal failure |

[31] | Central and peripheral nervous system impairment Hematopoiesis problems, microcytic anemia Gastrointestinal disturbances Renal failure. |

[32] [33] [34] |

| Mercury (Hg) | Cats | Similar neurological symptoms to Minamata disease: ataxia, weakness, loss of balance, and motor incoordination | [35] [36] |

Neurological symptoms: uncontrollable tremors, muscular incoordination, slurred speech, partial blindness | [37] |

Canine mesothelioma is described as being linked to lifestyle, diet, and asbestos exposure, but the most cases have occurred in canine companions whose owners worked in environments with asbestos or used flea repellents in which the talc was contaminated with asbestos [38]. The human and canine malignant mesotheliomas are clinically and morphologically similar [39], but the latency period is much shorter in dogs (8 years) than in humans (up to 20 years) [38]. As for the effects of acute asbestos exposure, in a 15-year surveillance study in search-and-rescue dogs Otto et al. [40] reported no difference in the cause of death of dogs exposed to several classes of toxicants (including heavy metals and asbestos, during deployment at terrorist attack sites) compared to unexposed dogs.

Lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), and mercury (Hg) are all heavy metals/metalloids with adverse health effects, and their latency period is also shorter in pets compared to humans [41]. The absorption, metabolization, transformations, and toxicity of these substances in pets is the most similar to that of young children, which makes companion animals even more valuable in early detection [42]. In a 2005 study, Park et al. [43] concludes that dogs can be considered biomonitors of the environmental quality assessment for cadmium, lead, and chromium contamination, and at least for lead and cadmium cats showed the same conclusive results (Table 2).

Table 2. Average values of heavy metals found in the blood and certain organs of clinically healthy † pets from different polluted geographical areas.

| Country | U.M. | Heavy Metals (Mean ± SD) | Analyzed From | No. of Samples | Species | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Cd | Cr | Hg | As | ||||||

| Korea | μg/mL | 0.68 ± 0.19 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.66 ± 0.15 | 1.10 ± 0.49 | - | Serum | 204 | Dogs | [43] |

| Zambia | μg/L | 271.6 ± 226.9 | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 67.2 ± 75.4 | - | 5.2 ± 4.5 | Blood | 120 | Dogs | [44] |

| Italy (Campania) | mg/kg | 0.321 ± 0.198 | 0.093 ± 0.079 | - | 0.054 ± 0.044 | - | Liver | 38 | Dogs | [45] |

| 0.293 ± 0.231 | 0.259 ± 0.238 | - | 0.040 ± 0.021 | - | Kidney | |||||

| Italy (Naples) |

mg/Kg | 0.256 ± 0.130 | 0.098 ± 0.063 | - | - | - | Liver | 290 | Dogs | [46] |

| 0.147 ± 0.081 | 0.302 ± 0.212 | - | - | - | Kidney | |||||

| 0.268 ± 0.107 | 0.101 ± 0.054 | - | - | - | Liver | 88 | Cats | |||

| 0.189 ± 0.102 | 0.355 ± 0.144 | - | - | - | Kidney | |||||

| Italy (South Sardinia) | ng/mL | 81.4 ± 16.6 | 52.2 ± 14.0 | - | - | 139 ± 39 | Ovaries | 26 | Cats | [47] |

| 20.4 ± 3.6 | 19.7 ± 4.0 | - | - | 21.7 ± 4.2 | Ovaries | 21 | Dogs | |||

| Italy (North Sardinia) | ng/mL | 51.1 ± 17.9 | 26.4 ± 5.5 | - | - | 107 ± 61 | Ovaries | 14 | Cats | |

| 12.2 ± 5.2 | 12.2 ± 1.8 | - | - | 21.8 ± 3.9 | Ovaries | 24 | Dogs | |||

| Poland | 2.829 ± 3.490 ** 1.55 ± 1.71 ** |

0.105 ± 0.067 ** 0.096 ± 0.074 ** |

0.0020 ± 0.0013 * 0.0027 ± 0.0022 ** |

Cartilage and compact bone Spongy bone |

24 | Dogs | [48] | |||

| Poland | μg/mL | 0.419 ± 0.027 | 0.302 ± 0.049 | 0.244 ± 0.016 | - | 0.637 ± 0.277 | Serum | 48 | Dogs | [49] |

| Spain | μg/mL | 0.55 ± 0.60 | - | 2.73 ± 2.54 | 0.24 ± 0.22 | 1.86 ± 1.44 | - | 42 | Dogs | [50] |

| Jamaica West Indies | μg/mL | 2.83 ± 0.40 | - | - | - | - | Serum | 63 | Dogs | [51] |

| New Zealand | μg/mL | 0.23 ± 0.66 | - | - | - | - | - | 271 | Dogs | [52] |

| 0.21 ± 0.05 | - | - | - | - | - | 113 | Cats | |||

† One of the referenced papers [46] reports the heavy metal concentrations found in the tissues of animals deceased in an incident. U.M.: unit of measurement; * lower values than in humans; ** higher values than in humans.

Although the concentration of heavy metals can be measured in various samples, the liver and kidney tissue are preferred, especially for cadmium and lead exposure [45,46]. Once absorbed, lead is redistributed in the soft tissues [48], but most of it (90%) is accumulated in bones and teeth [48], with a half-life of 25 years in humans [53].

The benefits of using animal sentinels to evaluate environmental lead pollution have been recognized for more than 40 years [54]. This is extremely relevant, especially when pets live in proximity to children. Preventing exposure to lead during nervous system development is very important because of the damage this heavy metal can cause [55]. The tremendous benefit of this approach is that the blood tests of sentinels can provide early warnings without having to analyze a child’s brain [4]. As early as 1976, the comparative analysis of serum samples collected from 119 children and 94 dogs from suburban Illinois demonstrated that canine companions can be considered sentinels of lead poisoning in children [54]. The presence of lead in the blood of pets may indicate potential exposure of humans, especially of young children, to the polluted environment is also the conclusion reached by Berny et al. [56]. For possible lead contamination in children, the prediction is based on canine and feline serum values which exceed the physiologic threshold of the species 2–4 times [2,57]. However, for the results to be conclusive, variables such as sex, age, and behaviors influencing exposure of the companion animals must be taken into consideration. Although the blood levels of lead are usually higher in males, Toyomaki et al. [44] reports for one of their research areas a significantly higher lead contamination of female dogs, especially in the older ones. The authors’ supposition is that male dogs may wander more (thus leaving the polluted areas), while the females stay for longer while raising their puppies in the same (polluted) place.

After the period in which the sentinel role of companion animals for environmental asbestos and heavy metal pollution detection was proven by testing their blood and especially tissues (to verify chronic exposure) illustrated by many reports (Table 2), the research continued to find more non-invasive approaches [58]. In this context, Petrov et al. [59], and Nikolovski and Atanaskova [60] believe that using hair as a testing matrix brings significant advantages in terms of ease of collection and a more animal welfare friendly attitude compared to tissue sampling. As Table 3 shows, the concentration of several heavy metals has been tested in different countries by analyzing hair samples of the companion animals exposed to these pollutants.

Table 3. Mean values of heavy metals obtained by testing pet hair samples.

| Country | UM | Heavy Metals (Mean ± SD) | AM | No. of Samples |

Species | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Cd | Cr | Hg | As | ||||||

| Macedonia | μg/kg | |||||||||

| Veles | 930.15 ± 516.03 | 54.28 ± 12.77 | - | - | - | AAS | 11 | Dog | [59] | |

| Bitola | 715.66 ± 293.80 | 42.65 ± 25.41 | - | - | - | 22 | Dog | |||

| Prilep | 525.63 ± 253.91 | 27.82 ± 8.31 | - | - | - | 11 | Dog | |||

| Macedonia | μg/kg | |||||||||

| Delcevo | 579 ± 478.29 | 68.57 ± 59.95 | - | - | - | AAS | 18 | Dog | [60] | |

| Probistip | 1061.38 ± 564.02 | 26.86 ± 23.30 | - | - | - | 20 | Dog | |||

| Veles | 1099.02 ± 593.01 | 171.54 ± 179.53 | - | - | - | 17 | Dog | |||

| Prilep | 370.57 ± 288.39 | 21.65 ± 10.64 | - | - | - | 18 | Dog | |||

| Bitola | 687.05 ± 482.82 | 66.04 ± 73.78 | - | - | - | 21 | Dog | |||

| Australia | mg/kg−1 DW | 1.19 ± 3.11 | - | 0.85 ± 1.42 | 0.13 ± 0.11 | 0.08 ± 0.06 | AAS | 36 | Dog | [61] |

| Argentina | mg/g DW−1 | - | - | - | - | 24 ± 2 | TXRF technique | - | Dog | [62] |

| Portugal | μg/g−1 | 24 ± 2.4 | TXRF | 50 | Dog | [63] | ||||

| Portugal | ng/g−1 | - | - | - | 24.16–826.30 | TXRF technique | 26 | Dog | [64] | |

| Poland | mg/kg−1 | - | - | - | 0.025 ± 0.020 | AAS | 85 | Cat | [65] | |

| Iran | ng/g DW | - | - | - | AAS | 40 | Wild cats | [66] | ||

| North-west | - | - | - | 735 ± 456 | ||||||

| North | - | - | - | 568 ± 381 692 ± 577 |

||||||

| Center | - | - | - | 1303 ± 1306 376 ± 162 |

||||||

| North-east | - | - | - | 1517 ± 1888 | ||||||

| West | - | - | - | 231 ± 89 | ||||||

| Japan | ppm | - | - | - | 7.40 ± 2.93 | AAS | 12 | Male cat | [67] | |

| - | - | - | 7.45 ± 1.28 | 29 | Female cat | |||||

| - | - | - | 0.99 ± 0.23 | 16 | Male dog | |||||

| - | - | - | 0.66 ± 0.10 | 18 | Female dog | |||||

| Alaska | ng/g | 1822.4 ± 1747 | - | Sled dog | [68] | |||||

UM—unit of measurement; DW—dry weight; AAS—atomic absorption spectrometry; AM—analysis method; TXRF—total reflection X-ray fluorescence analysis.

While testing canine hair, Jafari [61] observed a strong positive linear correlation between the contamination of the soil and the hair with chromium, copper, lead, and mercury, and to a lesser extent with zinc, and a negative correlation with arsenic. Promising results were obtained by testing feline hair too, for environmental lead pollution [69]. Aeluro and Kavanagh [69] found higher lead concentrations in the hair of female cats than of the males, but the authors report that these animals were more exposed (spent more time outdoors) compared to the males.

Similarly, to organ tissues, hair samples are the most proper when long-term exposure is suspected [70]. Through their follicles, the hairs are connected to the blood flow, extracting and incorporating not only the nutrients necessary for growth but other elements as well. Because keratin has a good metal-binding affinity, these elements become ‘trapped’ in the cortex and cuticle of the hairs [71], allowing for their testing. As opposed to blood, which is primarily a transport medium and deposits the absorbed substances readily (leading to content fluctuations), hair is a more stable medium for the identification of deposit substances such as minerals and metals [72]. By these characteristics, the hair samples reach a higher similarity relevance as the internal organs for testing chronic exposure to heavy metals irrespective of the exposure source and access ways inside the organism (whether these are air, food, or waterborne pollutants, or if they cross the skin barrier directly from the outside environment).

2.2. Pets as Sentinels for Heavy Metals in Water and Food

Food and waterborne heavy metal intoxications have been documented several times in the scientific literature. The pollution of surface waters with heavy metals is a concerning situation that needs special corrective measures or simply limits on the drinkability of that water source. One such situation exists in Argentina, where many regions are known as chronic regional endemic hydro arsenic zones due to the arsenic contamination of the water. A special contribution to the early detection of chronic waterborne arsenic exposure is canine hair, according to Vázquez et al. [62], with higher values (thus easier to test) than in human hair or the water itself (evidently).

Most of the pollutants in water and food come from the environment, but they significantly increase the health hazards to human and animal populations. The inhabitants of a polluted area (people and pets) will not only be exposed to the direct effect of the pollutant in their environment (from air, soil, contact surfaces) but will receive additional pollutant doses while they eat or drink. In some cases, plant- and animal-origin food is even more dangerous because of the accumulation of pollutants in these. For terrestrial or marine environmental contaminants, such as mercury accumulated in dietary products, sled dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) in the Arctic regions are sentinels for the local communities regarding the possible risks associated with the food they consume. The better they fit this role as mercury absorption, accumulation, and excretion in dogs are similar to humans [73,74,75]. Even the blood-to-hair mercury ratio in dogs (200) is similar to that described in humans [64]. Because there is a highly significant positive correlation between the total mercury in canine blood and hair, dogs can be reliable sentinels of mercury exposure regardless of the sampling method used for quantifying [64,68].

Cats suffer pathological changes from oral methylmercury poisoning similar to those produced in humans suffering from the disease called Minamata disease, discovered in 1959, but whose initial results were never published [76]. The experiment, later repeated by Eto et al. [77], involved sprinkling the cats’ food with liquid mercury, which led to observations related to the accumulation of the metalloid in the cerebrum, cerebellum, liver, and kidney. In both humans and cats, mercury poisoning has the same symptoms, the incoordination known as “dancing cats of Minamata” being an early warning sign of intoxication [78].

Most of the time, oral poisoning with mercury occurs as a result of mercury-polluted pet food. In feline companions, mercury accumulation is influenced by age and sex. In geriatric males, the accumulation begins earlier compared to females and has slightly higher values [67]. Similar to dogs, it was proven that there is a strong correlation between the mercury content in the cats’ hair and that found in their liver and kidneys after the ingestion of mercury-polluted foods. Hence, the conclusion drawn by Skibniewska and Skibniewski [65] is that feline hair can provide an indication of mercury exposure, and its concentration is correlated with the existing loads in other vital organs (liver: 0.030 ± 0.031, kidney: 0.026 ± 0.025 mg⋅kg−1). Wild cat hair lends itself equally well to environmental biomonitoring, according to Behrooz et al. [66].

The first alarm signal about the potential danger that threatens the integrity of human health is the accumulation of mercury values five times higher in the body of pets compared to that in the human body [79].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ani13182923

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!