Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Bivalve molluscan shellfish have been consumed for centuries. Being filter feeders, they may bioaccumulate some microorganisms present in coastal water, either naturally or through the discharge of human or animal sewage. Despite regulations set up to avoid microbiological contamination in shellfish, human outbreaks still occur.

- seafood microbial contamination

- pathogen emergence

- surveillance

1. Marine and Enteric Bacteria

Among the bacterial pathogens, the Vibrio species, including V. parahaemolyticus, V. cholerae and V. vulnificus, have been extensively studied as key agents responsible for shellfish borne diseases, especially in shellfish like oysters, mussels and ark shells, and particularly during warmer months, when their populations surge [17,18,19]. More recent research has shed light on Aeromonas pathogenic species, with studies emcompassing the virulence and emergence of drug-resistant Aeromonas in seafood [20,21,22]. The authors advocate for paying increased attention to these pathogens, particularly considering the context of global warming and its effect on water temperatures.

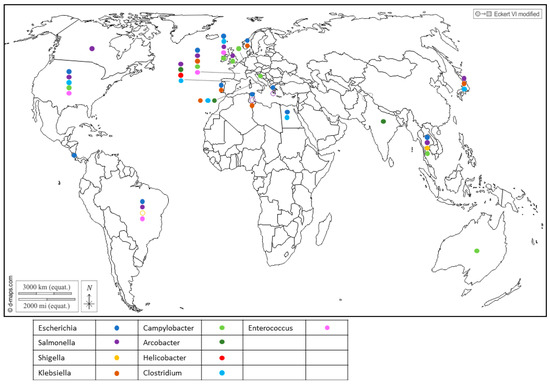

Furthermore, Enterobacteriaceae regroups important seafood-borne pathogens, and include genera like Escherichia [23,24], Shigella which was reported in Japan [25], Salmonella [26,27,28,29,30,31] and Klebsiella in Portugal [32], Tunisia [33] and Italy [34], which have drawn attention to their health threats and their contribution to the spread of antibiotic resistance in the environment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Worldwide distribution of bacterial genera frequently detected in BMS (freshwater or marine) per country. Full circles show the detection of bacteria in a country (by isolation or PCR), according to the color code in the legend (blue: Escherichia; purple: Salmonella; yellow: Shigella; brown: Klebsiella; light green: Campylobacter; dark green: Arcobacter; red: Helicobacter; light blue: Clostridium; pink: Enterococcus). Empty circles report that the bacterium was assessed but never detected in the country, following the same color code. Up to 5 different genera were detected in a single country.

Salmonella is a zoonotic pathogen transmitted from animals to humans through foodstuffs and can contaminate shellfish through fecal contamination from animals or contaminated water sources. Similarly, Campylobacter bacteria share the spotlight with Salmonella as major causes of foodborne illness and can also be found in shellfish, suggesting contamination from environmental sources like water and bird excreta. They encompass species such as C. jejuni, which is associated with poultry and bovines, playing a prominent role in human infections; C. coli, linked to poultry and pork; and C. lari, which is a more recent group [19,35,36,37,38]. Recent studies showed that C. lari is particularly associated with shellfish contamination [36,39]. The risk of infection from the consumption of raw shellfish was estimated to be 5–20% for mussels and 2–10% for oysters [35].

Recent reports have highlighted the presence of Helicobacter pylori in Spanish commercial shellfish [40] (Figure 1), adding to concerns about food safety. This bacterium, known for its role in causing gastric ulcers and other gastrointestinal disorders in humans, being detected in shellfish raises questions about the potential health risks associated with shellfish consumption. Additionally, pathogenic Arcobacters like A. butzleri and A. cryaerophilus have garnered attention for their association with seafood-related infections and their ability to develop antibiotic resistance [41,42]. A. butzleri has commonly been associated with various animals, including poultry, swine, cattle and shellfish (Figure 1), as well as with some human infections. On the other hand, A. cryaerophilus has been detected in a variety of sources, such as the environment, food products and animal intestines, but its association with human infections has been less well-established compared to A. butzleri. This may be due, in part, to their optimal growth temperature, as A. butzleri tends to grow optimally at temperatures around 30–37 °C, while A. cryaerophilus has an optimal growth temperature range of 25–30 °C [43,44].

In addition, gram-positive bacteria also inhabit shellfish. Enterococcus was found in cockles, oysters and mussels (Figure 1), and serves as a widely utilized indicator organism for assessing water contamination, particularly in recreational waters such as beaches and lakes [19]. Several species were reported in shellfish in Northern Ireland, with Enterococcus faecalis and E. faecium being the most frequently encountered [45] (Figure 1). Of note, four isolates of E. faecalis from the shellfish used in this study were highly resistant to vancomycin (Vancomycin-resistant enterococci, or VRE). Usually encountered in hospitals and long-term care facilities, this resistance poses a significant challenge as VRE infections are difficult to treat and can spread easily.

Alongside Enterococcus, Clostridium bacteria have been identified in shellfish (Figure 1). While C. butyricum is generally considered to be non-pathogenic [46], C. perfrigens [47,48] and C. difficile [49,50,51,52] pose a significant risk of causing severe gastrointestinal infections. The anaerobic or microaerobic growth requirements of certain pathogens render their isolation for risk assessment challenging.

Notably, a considerable number of the cited pathogens belong to the ESKAPEE group, which includes E. faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp. and E. coli. These opportunistic pathogens are also considered to be emerging pathogens and serve as significant reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes.

2. Human and Animal Enteric Viruses

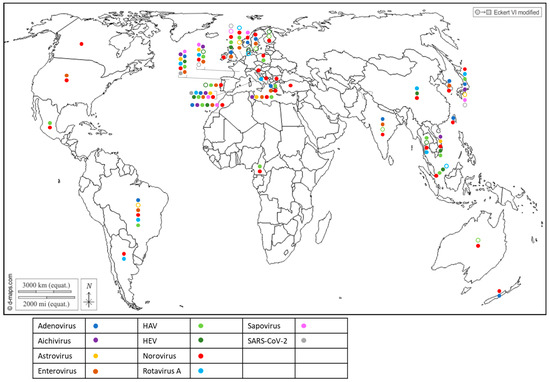

The first attempts to detect human viruses in BMS relied on virus cultivation in mammalian cells, which allowed culturable viruses such as enteroviruses [53] or hepatitis A virus [54] to be identified. Since the 1990s, progress in molecular biology has enabled the identification of many other human viruses in BMS worldwide (Figure 2) through conventional PCR, PCR and probe hybridization, quantitative PCR and, more recently, digital PCR. Most of these human viruses are considered to be enteric pathogens and known to be present in the stool of infected individuals and in human sewage [55]: adenovirus (AdV), aichivirus (AiV), astrovirus (AsV), enterovirus (EV), hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis E virus (HEV), norovirus (NoV GI, GII, GIV), rotavirus A (RV) and sapovirus (SaV). Other non-enteric viruses that are present in human excreta were also detected in BMS, such as SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 2), human polyomavirus JC [56,57] and the Merkel-cell polyomavirus [58]. In addition to these well-known human viruses, human bocaviruses, which are emerging enteric and/or respiratory viruses first identified in 2005 and are present in human sewage, were detected in BMS in all of the studies in which they were assessed [59,60,61,62,63], including in Italy, South-Africa, Thailand and Brazil. Human circoviruses, another group of recently discovered ubiquitous viruses also present in human stools, were detected in BMS in Norway [64].

Figure 2. Worldwide distribution of 10 human viruses frequently detected in BMS (freshwater or marine) per country. Full circles denote the detection of a virus in a country, according to the color code in the legend (blue: Adenovirus; purple: Aichivirus; yellow: Astrovirus; brown: Enterovirus; light green: HAV; dark green: HEV; red: Norovirus; light blue: Rotavirus; pink: Sapovirus; grey: SARS-CoV-2). Empty circles report that the virus was assessed but never detected in the country, following the same color code. Up to 10 of these viruses were detected in a single country.

Together, these studies report the worldwide exposure of BMS to human sewage, and show that BMS can be contaminated by multiple viral species, provided that these viruses are circulating in the local population and present in sewage. They also highlight the need for more data in poorly studied regions of the world, mainly Africa and South and Central America, but also North America and Oceania, where few studies have been conducted (or published) on viral contaminants in BMS and those few studies pertained to a limited set of human viruses. Finally, they show that emerging or newly discovered viruses (HEV, SARS-CoV-2, human bocavirus and circovirus) could be detected in BMS, which emphasizes the potential contribution of BMS in the propagation of emerging pathogens.

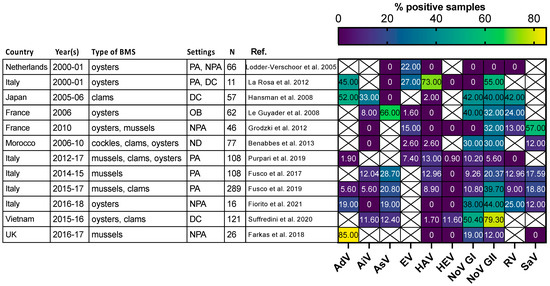

Most of the human viruses assessed in BMS could be found, according to these studies, but some were detected more sporadically than others. For instance, human NoV were detected in most of the studies in which they were screened for (Figure 2, red full circles), while HEV and SARS-CoV-2 often remained undetected (Figure 2, green and gray empty circles). Interestingly, 12 studies reported the screening of multiple human viruses in the same BMS sample set, allowing their respective frequencies to be compared in identical settings (Figure 3) [56,60,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74]. Human NoV (GI, GII or both) were detected in all of these studies but one and were the most or second most frequent virus in each (Figure 3). Human AdV and EV were always detected when assessed, albeit with varying frequencies. Conversely, human AiV, AsV, HAV, HEV, RV and SaV were detected in a smaller proportion of samples and remained undetected in some studies. Hence, human NoV appear as one of the most frequent human viruses in BMS, which is consistent with the vast amount of publications regarding this contamination, as reviewed in [14]. However, other human viruses are often present in NoV-contaminated shellfish, and sometimes in NoV-negative ones (Figure 3). Thus, the current focus on NoV in BMS likely masks the contribution of other viruses. The different frequencies of human viruses in BMS may reflect their respective levels of circulation in the human population, concentration in stool and sewage, persistence in the environment and/or affinity for shellfish tissues [75]. More studies are needed to assess these different hypotheses and to better understand the drivers of BMS contamination by the different human viruses present in sewage. In turn, this knowledge will help in designing adequate surveillance systems considering the viral threats that are relevant locally.

Figure 3. Comparison of enteric virus frequency in BMS screened for multiple viruses in 11 studies. The proportion of samples positive for each studied virus (x-axis) in 11 studies (y-axis) is plotted as a heatmap. Studies were selected for assessing at least 5 different enteric viruses through conventional or quantitative PCR. They were conducted in the Netherlands, Japan, France, Morocco, Italy, Vietnam and UK at different periods between 2000 and 2018. Different types of BMS (Oysters, mussels, clams and cockles) were sampled either from areas not open for production (NPA), producing areas (PA), the distribution chain (DC), which includes dispatch centers, retails, markets or restaurants, or in relation to human outbreak investigation (OB). In one case the setting was not disclosed (ND). The number of studied samples varied from 11 to 289. Human AdV and EV were consistently detected, with varying frequencies. Human NoV (GI, GII or both) were detected in all studies but one and often displayed the highest or second highest frequency. Other viruses were detected at lowest frequencies and remained undetected in some of them. References cited [56,60,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74].

In addition to human viruses, BMS were found to be contaminated by mammalian animal viruses belonging to the same viral families—such as porcine or bovine NoV [76,77,78], porcine SaV [77], bovine polyomavirus [58], G8P [1] bovine-like rotavirus [79] or porcine circovirus [80]—in studies using targeted means, such as quantitative PCR. Metagenomics approaches to sequencing all of the viral material in a sample were also applied to BMS in one study where other animal viruses related to AsV or NoV were detected [81]. Targeted metagenomics applied to contaminated BMS revealed that a high diversity of NoV strains belonging to various genotypes can be present in a single sample, including strains of animal origin [82,83,84]. The same approach has shown the presence of animal, mainly avian, astroviruses in mussels [85]. This highlights the potential of BMS to contribute to the transmission of zoonotic viruses and the need to consider this risk for future surveillance strategies.

Detecting and identifying the multiple viruses and viral strains within a viral genus that can be present in a single BMS sample represents a challenge for the future surveillance of BMS quality, for which next-generation sequencing approaches hold much promise, as discussed below. Another important challenge is to evaluate the actual infectious risk posed by a contaminated BMS when some viral genomic material is detected.

3. Bacteria-Virus Interactions and Co-Occurrence

The studies reviewed above have shown the large diversity of bacterial and viral pathogens contaminating BMS worldwide. Meanwhile, the current monitoring strategies still focus on E. coli as a marker of fecal contamination. In some studies, there was a modest correlation between E. coli and NoV in BMS, especially in winter [86,87,88]. Indeed, the E. coli-based classification of production areas is able to partially protect against the commercialization of NoV-contaminated BMS [88] and, in Europe, BMS from class A areas were less frequently contaminated by NoV than those from class B areas [89]. However, several studies have shown that this marker is not well-correlated to contamination by human NoV in BMS [19,90,91]. This is likely due to differences in their dissemination in the land–sea continuum [92,93] and different interactions with the BMS matrix—E. coli contamination being transient, while viruses are more stable [94]. Moreover, E. coli is not always correlated to other enteric bacteria in BMS [19,95] and is unlikely to be correlated to marine bacteria like Vibrio; however, such a relationship has not been studied to date. Similar concerns have been raised in subtropical regions [96]. Beyond E. coli and NoV, few studies have addressed the possible correlation between human enteric bacteria and viruses in BMS, while they originate from the same contamination source—sewage. These first data suggest that interactions may be species- and season-specific [19,88]. This in agreement with reports of direct interactions between human NoV and some strains of enteric bacteria (reviewed in [97]), which may also exist for other viruses. Understanding the possible patterns and mechanisms of co-occurrence between the different bacterial and viral pathogens contaminating BMS remains a challenge, but could help in conceiving optimized surveillance strategies for multiple pathogens in BMS.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms11092218

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!