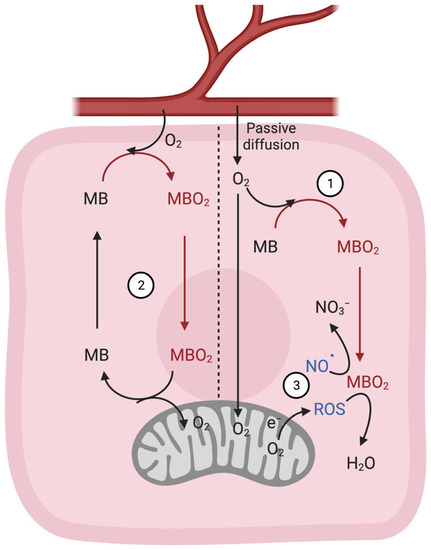

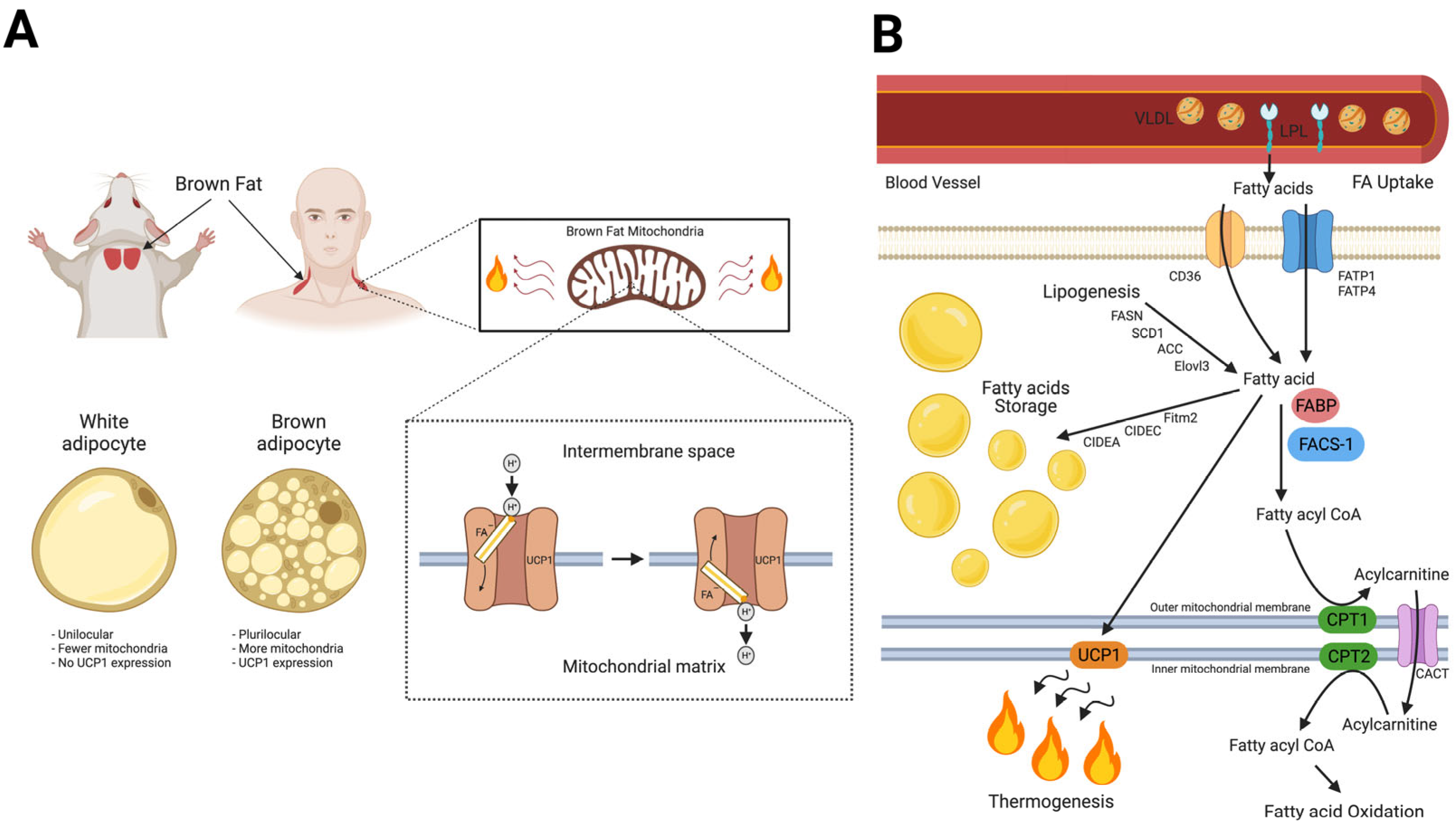

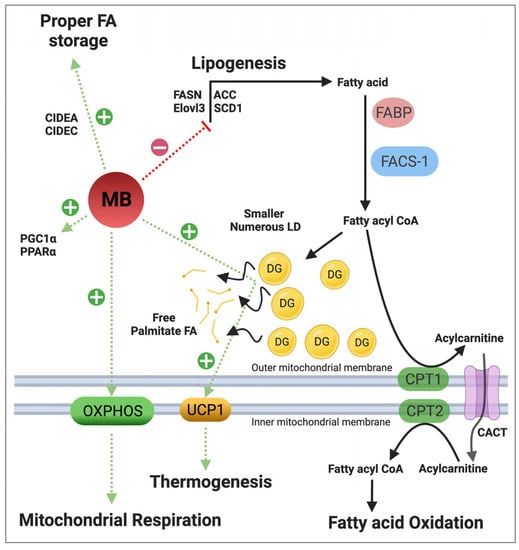

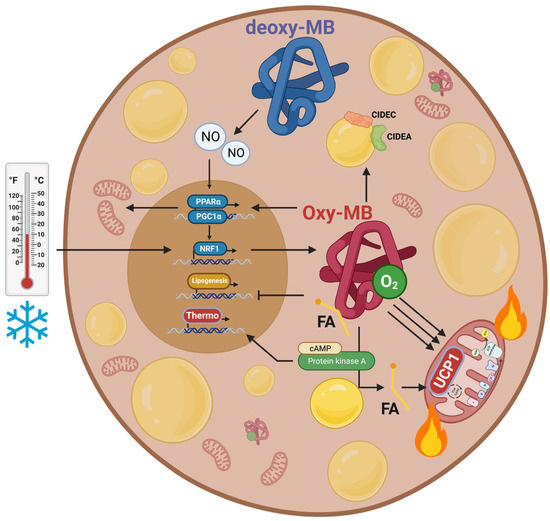

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) plays an important role in energy homeostasis by generating heat from chemical energy via uncoupled oxidative phosphorylation. Besides its high mitochondrial content and its exclusive expression of the uncoupling protein 1, another key feature of BAT is the high expression of myoglobin (MB), a heme-containing protein that typically binds oxygen, thereby facilitating the diffusion of the gas from cell membranes to mitochondria of muscle cells. In addition, MB also modulates nitric oxide (NO•) pools and can bind C16 and C18 fatty acids, which indicates a role in lipid metabolism. Studies in humans and mice implicated MB present in BAT in the regulation of lipid droplet morphology and fatty acid shuttling and composition, as well as mitochondrial oxidative metabolism.

- brown adipose tissue

- myoglobin

- mitochondrial oxidative metabolism

- energy metabolism

1. Introduction

2. Structure, Location, and Classical Functions of MB

2.1. Structure

2.2. Location

2.3. Classic Gas-Binding Functions

3. Fatty Acid Homeostasis in BAT Thermogenesis and Novel Roles of MB in Lipid Metabolism

4. Myoglobin in BAT; State-of-the-Art Research

4.1. Expression

4.2. Regulation of Mitochondrial Metabolism and UCP1 Expression

4.3. Regulation of Lipid Metabolism

4.4. Regulation of NO• Metabolism

4.5. Regulation of Energy Expenditure and Clinical Implications

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells12182240

References

- Lankester, E.R. Ueber das Vorkommen von Haemoglobin in den Muskeln der Mollusken und die Verbreitung desselben in den lebendigen Organismen. Arch. Gesamte Physiol. Menschen Tiere 1871, 4, 315–320.

- Günther, H. Über den Muskelfarbstoff. Virchows Arch. Pathol. Anat. Physiol. Klin. Med. 1921, 230, 146–178.

- Kendrew, J.C.; Dickerson, R.E.; Strandberg, B.E.; Hart, R.G.; Davies, D.R.; Phillips, D.C.; Shore, V.C. Structure of myoglobin: A three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2 A. resolution. Nature 1960, 185, 422–427.

- Kendrew, J.C.; Bodo, G.; Dintzis, H.M.; Parrish, R.G.; Wyckoff, H.; Phillips, D.C. A three-dimensional model of the myoglobin molecule obtained by x-ray analysis. Nature 1958, 181, 662–666.

- Endeward, V.; Gros, G.; Jürgens, K.D. Significance of myoglobin as an oxygen store and oxygen transporter in the intermittently perfused human heart: A model study. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 87, 22–29.

- Gödecke, A.; Flögel, U.; Zanger, K.; Ding, Z.; Hirchenhain, J.; Decking, U.K.; Schrader, J. Disruption of myoglobin in mice induces multiple compensatory mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 10495–10500.

- Grange, R.W.; Meeson, A.; Chin, E.; Lau, K.S.; Stull, J.T.; Shelton, J.M.; Williams, R.S.; Garry, D.J. Functional and molecular adaptations in skeletal muscle of myoglobin-mutant mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2001, 281, C1487–C1494.

- Saito, M.; Matsushita, M.; Yoneshiro, T.; Okamatsu-Ogura, Y. Brown Adipose Tissue, Diet-Induced Thermogenesis, and Thermogenic Food Ingredients: From Mice to Men. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 222.

- Din, M.U.; Saari, T.; Raiko, J.; Kudomi, N.; Maurer, S.F.; Lahesmaa, M.; Fromme, T.; Amri, E.Z.; Klingenspor, M.; Solin, O.; et al. Postprandial Oxidative Metabolism of Human Brown Fat Indicates Thermogenesis. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 207–216.

- Forner, F.; Kumar, C.; Luber, C.A.; Fromme, T.; Klingenspor, M.; Mann, M. Proteome Differences between Brown and White Fat Mitochondria Reveal Specialized Metabolic Functions. Cell Metab. 2009, 10, 324–335.

- Timmons, J.A.; Wennmalm, K.; Larsson, O.; Walden, T.B.; Lassmann, T.; Petrovic, N.; Hamilton, D.L.; Gimeno, R.E.; Wahlestedt, C.; Baar, K.; et al. Myogenic gene expression signature establishes that brown and white adipocytes originate from distinct cell lineages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 4401–4406.

- Aboouf, M.A.; Armbruster, J.; Thiersch, M.; Gassmann, M.; Goedecke, A.; Gnaiger, E.; Kristiansen, G.; Bicker, A.; Hankeln, T.; Zhu, H.; et al. Myoglobin, expressed in brown adipose tissue of mice, regulates the content and activity of mitochondria and lipid droplets. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 159026.

- Armbruster, J.; Aboouf, M.A.; Gassmann, M.; Egert, A.; Schorle, H.; Hornung, V.; Schmidt, T.; Schmid-Burgk, J.L.; Kristiansen, G.; Bicker, A.; et al. Myoglobin regulates fatty acid trafficking and lipid metabolism in mammary epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275725.

- Chintapalli, S.V.; Jayanthi, S.; Mallipeddi, P.L.; Gundampati, R.; Kumar, T.K.S.; van Rossum, D.B.; Anishkin, A.; Adams, S.H. Novel Molecular Interactions of Acylcarnitines and Fatty Acids with Myoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 251133–251143.

- Hendgen-Cotta, U.B.; Esfeld, S.; Coman, C.; Ahrends, R.; Klein-Hitpass, L.; Flögel, U.; Rassaf, T.; Totzeck, M. A novel physiological role for cardiac myoglobin in lipid metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43219.

- Schlater, A.E.; De Miranda, M.A.; Frye, M.A.; Trumble, S.J.; Kanatous, S.B. Changing the paradigm for myoglobin: A novel link between lipids and myoglobin. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 117, 307–315.

- Schlater, A.E.; De Miranda, M.A.; Corley, A.M.; Kanatous, S.B. Lipid stimulates myoglobin expression in skeletal muscle cells. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 1078.16.

- Blackburn, M.L.; Wankhade, U.D.; Ono-Moore, K.D.; Chintapalli, S.V.; Fox, R.; Rutkowsky, J.M.; Willis, B.J.; Tolentino, T.; Lloyd, K.C.K.; Adams, S.H. On the potential role of globins in brown adipose tissue: A novel conceptual model and studies in myoglobin knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 321, E47–E62.

- Christen, L.; Broghammer, H.; Rapohn, I.; Mohlis, K.; Strehlau, C.; Ribas-Latre, A.; Gebhardt, C.; Roth, L.; Krause, K.; Landgraf, K.; et al. Myoglobin-mediated lipid shuttling increases adrenergic activation of brown and white adipocyte metabolism and is as a marker of thermogenic adipocytes in humans. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e1108.

- Gotz, F.M.; Hertel, M.; Groschelstewart, U. Fatty-Acid-Binding of Myoglobin Depends on Its Oxygenation. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 1994, 375, 387–392.

- Jue, T.; Simond, G.; Wright, T.J.; Shih, L.F.; Chung, Y.R.; Sriram, R.; Kreutzer, U.; Davis, R.W. Effect of fatty acid interaction on myoglobin oxygen affinity and triglyceride metabolism. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 73, 359–370.

- Gorr, T.A.; Wichmann, D.; Pilarsky, C.; Theurillat, J.P.; Fabrizius, A.; Laufs, T.; Bauer, T.; Koslowski, M.; Horn, S.; Burmester, T.; et al. Old proteins–new locations: Myoglobin, haemoglobin, neuroglobin and cytoglobin in solid tumours and cancer cells. Acta Physiol. 2011, 202, 563–581.

- Nelson, D.L.; Cox, M.M.; Lehninger, A.L. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, 7th ed.; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA; Basingstoke, UK, 2017; I45p.

- Springer, B.A.; Egeberg, K.D.; Sligar, S.G.; Rohlfs, R.J.; Mathews, A.J.; Olson, J.S. Discrimination between oxygen and carbon monoxide and inhibition of autooxidation by myoglobin. Site-directed mutagenesis of the distal histidine. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 3057–3060.

- Fraser, J.; de Mello, L.V.; Ward, D.; Rees, H.H.; Williams, D.R.; Fang, Y.; Brass, A.; Gracey, A.Y.; Cossins, A.R. Hypoxia-inducible myoglobin expression in nonmuscle tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 2977–2981.

- Burmester, T.; Weich, B.; Reinhardt, S.; Hankeln, T. A vertebrate globin expressed in the brain. Nature 2000, 407, 520–523.

- Cossins, A.R.; Williams, D.R.; Foulkes, N.S.; Berenbrink, M.; Kipar, A. Diverse cell-specific expression of myoglobin isoforms in brain, kidney, gill and liver of the hypoxia-tolerant carp and zebrafish. J. Exp. Biol. 2009, 212 Pt 5, 627–638.

- Bicker, A.; Dietrich, D.; Gleixner, E.; Kristiansen, G.; Gorr, T.A.; Hankeln, T. Extensive transcriptional complexity during hypoxia-regulated expression of the myoglobin gene in cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 479–490.

- Aboouf, M.A.; Armbruster, J.; Guscetti, F.; Thiersch, M.; Gassmann, M.; Gorr, T.A. The role of myoglobin in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, PS19-17.

- Aboouf, M.A.; Armbruster, J.; Thiersch, M.; Guscetti, F.; Kristiansen, G.; Schraml, P.; Bicker, A.; Petry, R.; Hankeln, T.; Gassmann, M.; et al. Pro-Apoptotic and Anti-Invasive Properties Underscore the Tumor-Suppressing Impact of Myoglobin on a Subset of Human Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11483.

- Behnes, C.L.; Bedke, J.; Schneider, S.; Kuffer, S.; Strauss, A.; Bremmer, F.; Strobel, P.; Radzun, H.J. Myoglobin expression in renal cell carcinoma is regulated by hypoxia. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2013, 95, 307–312.

- Bicker, A.; Nauth, T.; Gerst, D.; Aboouf, M.A.; Fandrey, J.; Kristiansen, G.; Gorr, T.A.; Hankeln, T. The role of myoglobin in epithelial cancers: Insights from transcriptomics. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 45, 385–400.

- Brooks, J.J. Immunohistochemistry of soft tissue tumors. Myoglobin as a tumor marker for rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer 1982, 50, 1757–1763.

- Emoto, M.; Iwasaki, H.; Kikuchi, M.; Shirakawa, K. Characteristics of cloned cells of mixed mullerian tumor of the human uterus. Carcinoma cells showing myogenic differentiation in vitro. Cancer 1993, 71, 3065–3075.

- Eusebi, V.; Bondi, A.; Rosai, J. Immunohistochemical localization of myoglobin in nonmuscular cells. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1984, 8, 51–55.

- Flonta, S.E.; Arena, S.; Pisacane, A.; Michieli, P.; Bardelli, A. Expression and functional regulation of myoglobin in epithelial cancers. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 201–206.

- Kristiansen, G.; Rose, M.; Geisler, C.; Fritzsche, F.R.; Gerhardt, J.; Luke, C.; Ladhoff, A.M.; Knuchel, R.; Dietel, M.; Moch, H.; et al. Endogenous myoglobin in human breast cancer is a hallmark of luminal cancer phenotype. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 1736–1745.

- Lamovec, J.; Zidar, A.; Bracko, M.; Golouh, R. Primary bone sarcoma with rhabdomyosarcomatous component. Pathol. Res. Pract. 1994, 190, 51–60.

- Meller, S.; Bicker, A.; Montani, M.; Ikenberg, K.; Rostamzadeh, B.; Sailer, V.; Wild, P.; Dietrich, D.; Uhl, B.; Sulser, T.; et al. Myoglobin expression in prostate cancer is correlated to androgen receptor expression and markers of tumor hypoxia. Virchows Arch. 2014, 465, 419–427.

- Meller, S.; Van Ellen, A.; Gevensleben, H.; Bicker, A.; Hankeln, T.; Gorr, T.A.; Sailer, V.; Droge, F.; Schrock, F.; Bootz, F.; et al. Ectopic Myoglobin Expression Is Associated with a Favourable Outcome in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients. Anticancer. Res. 2016, 36, 6235–6241.

- Oleksiewicz, U.; Daskoulidou, N.; Liloglou, T.; Tasopoulou, K.; Bryan, J.; Gosney, J.R.; Field, J.K.; Xinarianos, G. Neuroglobin and myoglobin in non-small cell lung cancer: Expression, regulation and prognosis. Lung Cancer 2011, 74, 411–418.

- Kristiansen, G.; Hu, J.M.; Wichmann, D.; Stiehl, D.P.; Rose, M.; Gerhardt, J.; Bohnert, A.; ten Haaf, A.; Moch, H.; Raleigh, J.; et al. Endogenous Myoglobin in Breast Cancer Is Hypoxia-inducible by Alternative Transcription and Functions to Impair Mitochondrial Activity. A role in tumor suppression? J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 43417–43428.

- Aboouf, M.A.; Armbruster, J.; Guscetti, F.; Thiersch, M.; Boss, A.; Gödecke, A.; Winning, S.; Padberg, C.; Fandrey, J.; Kristiansen, G.; et al. Endogenous myoglobin expression in mouse models of mammary carcinoma reduces hypoxia and metastasis in PyMT mice. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7530.

- Garry, D.J.; Ordway, G.A.; Lorenz, L.N.; Radford, N.B.; Chin, E.R.; Grange, R.W.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Williams, R.S. Mice without myoglobin. Nature 1998, 395, 905–908.

- Merx, M.W.; Gödecke, A.; Flögel, U.; Schrader, J. Oxygen supply and nitric oxide scavenging by myoglobin contribute to exercise endurance and cardiac function. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1015–1017.

- Flogel, U.; Godecke, A.; Klotz, L.O.; Schrader, J. Role of myoglobin in the antioxidant defense of the heart. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 1156–1158.

- Flogel, U.; Merx, M.W.; Godecke, A.; Decking, U.K.; Schrader, J. Myoglobin: A scavenger of bioactive NO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 735–740.

- Hendgen-Cotta, U.B.; Merx, M.W.; Shiva, S.; Schmitz, J.; Becher, S.; Klare, J.P.; Steinhoff, H.J.; Goedecke, A.; Schrader, J.; Gladwin, M.T.; et al. Nitrite reductase activity of myoglobin regulates respiration and cellular viability in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 10256–10261.

- Cosby, K.; Partovi, K.S.; Crawford, J.H.; Patel, R.P.; Reiter, C.D.; Martyr, S.; Yang, B.K.; Waclawiw, M.A.; Zalos, G.; Xu, X.; et al. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 1498–1505.

- Gladwin, M.T.; Kim-Shapiro, D.B. The functional nitrite reductase activity of the heme-globins. Blood 2008, 112, 2636–2647.

- Huang, Z.; Shiva, S.; Kim-Shapiro, D.B.; Patel, R.P.; Ringwood, L.A.; Irby, C.E.; Huang, K.T.; Ho, C.; Hogg, N.; Schechter, A.N.; et al. Enzymatic function of hemoglobin as a nitrite reductase that produces NO under allosteric control. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 2099–2107.

- Brunori, M. Nitric oxide, cytochrome-c oxidase and myoglobin. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001, 26, 21–23.

- Brunori, M. Myoglobin strikes back. Protein Sci. 2010, 19, 195–201.

- Shiva, S.; Brookes, P.S.; Patel, R.P.; Anderson, P.G.; Darley-Usmar, V.M. Nitric oxide partitioning into mitochondrial membranes and the control of respiration at cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 7212–7217.

- Beaudry, J.L.; Kaur, K.D.; Varin, E.M.; Baggio, L.L.; Cao, X.; Mulvihill, E.E.; Stem, J.H.; Campbell, J.E.; Scherer, P.E.; Drucker, D.J. The brown adipose tissue glucagon receptor is functional but not essential for control of energy homeostasis in mice. Mol. Metab. 2019, 22, 37–48.

- Beaudry, J.L.; Kaur, K.D.; Varin, E.M.; Baggio, L.L.; Cao, X.M.; Mulvihill, E.E.; Bates, H.E.; Campbell, J.E.; Drucker, D.J. Physiological roles of the GIP receptor in murine brown adipose tissue. Mol. Metab. 2019, 28, 14–25.

- Kobilka, B.K. G protein coupled receptor structure and activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2007, 1768, 794–807.

- Wettschureck, N.; Offermanns, S. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 1159–1204.

- Chondronikola, M.; Volpi, E.; Borsheim, E.; Porter, C.; Saraf, M.K.; Annamalai, P.; Yfanti, C.; Chao, T.; Wong, D.; Shinoda, K.; et al. Brown Adipose Tissue Activation Is Linked to Distinct Systemic Effects on Lipid Metabolism in Humans. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1200–1206.

- Bartelt, A.; Bruns, O.T.; Reimer, R.; Hohenberg, H.; Ittrich, H.; Peldschus, K.; Kaul, M.G.; Tromsdorf, U.I.; Weller, H.; Waurisch, C.; et al. Brown adipose tissue activity controls triglyceride clearance. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 200–205.

- Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. Brown adipose tissue: Function and physiological significance. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 277–359.

- Mills, E.L.; Pierce, K.A.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Garrity, R.; Winther, S.; Vidoni, S.; Yoneshiro, T.; Spinelli, J.B.; Lu, G.Z.; Kazak, L.; et al. Accumulation of succinate controls activation of adipose tissue thermogenesis. Nature 2018, 560, 102–106.

- Golozoubova, V.; Hohtola, E.; Matthias, A.; Jacobsson, A.; Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. Only UCP1 can mediate adaptive nonshivering thermogenesis in the cold. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 2048–2050.

- Feldmann, H.M.; Golozoubova, V.; Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. UCP1 ablation induces obesity and abolishes diet-induced thermogenesis in mice exempt from thermal stress by living at thermoneutrality. Cell Metab. 2009, 9, 203–209.

- Divakaruni, A.S.; Humphrey, D.M.; Brand, M.D. Fatty acids change the conformation of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 36845–36853.

- Fedorenko, A.; Lishko, P.V.; Kirichok, Y. Mechanism of fatty-acid-dependent UCP1 uncoupling in brown fat mitochondria. Cell 2012, 151, 400–413.

- Bertholet, A.M.; Kirichok, Y. The Mechanism FA-Dependent H(+) Transport by UCP1. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2019, 251, 143–159.

- Davis, T.R.; Johnston, D.R.; Bell, F.C.; Cremer, B.J. Regulation of shivering and non-shivering heat production during acclimation of rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1960, 198, 471–475.

- Depocas, F.; Hart, J.S.; Heroux, O. Cold acclimation and the electromyogram of unanesthetized rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 1956, 9, 404–408.

- Frontini, A.; Cinti, S. Distribution and development of brown adipocytes in the murine and human adipose organ. Cell Metab. 2010, 11, 253–256.

- Cypess, A.M.; Lehman, S.; Williams, G.; Tal, I.; Rodman, D.; Goldfine, A.B.; Kuo, F.C.; Palmer, E.L.; Tseng, Y.H.; Doria, A.; et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1509–1517.

- Virtanen, K.A.; Lidell, M.E.; Orava, J.; Heglind, M.; Westergren, R.; Niemi, T.; Taittonen, M.; Laine, J.; Savisto, N.J.; Enerback, S.; et al. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1518–1525.

- Zingaretti, M.C.; Crosta, F.; Vitali, A.; Guerrieri, M.; Frontini, A.; Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J.; Cinti, S. The presence of UCP1 demonstrates that metabolically active adipose tissue in the neck of adult humans truly represents brown adipose tissue. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 3113–3120.

- Cinti, S. Between brown and white: Novel aspects of adipocyte differentiation. Ann. Med. 2011, 43, 104–115.

- Kozak, L.P.; Anunciado-Koza, R. UCP1: Its involvement and utility in obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32 (Suppl. S7), S32–S38.

- Nicholls, D.G.; Rial, E. A history of the first uncoupling protein, UCP1. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1999, 31, 399–406.

- Calderon-Dominguez, M.; Mir, J.F.; Fucho, R.; Weber, M.; Serra, D.; Herrero, L. Fatty acid metabolism and the basis of brown adipose tissue function. Adipocyte 2016, 5, 98–118.

- Available online: http://biogps.org/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Fournier, B.; Murray, B.; Gutzwiller, S.; Marcaletti, S.; Marcellin, D.; Bergling, S.; Brachat, S.; Persohn, E.; Pierrel, E.; Bombard, F.; et al. Blockade of the activin receptor IIb activates functional brown adipogenesis and thermogenesis by inducing mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 32, 2871–2879.

- Watanabe, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Kakuhata, R.; Okada, N.; Kajimoto, K.; Yamazaki, N.; Kataoka, M.; Baba, Y.; Tamaki, T.; Shinohara, Y. Synchronized changes in transcript levels of genes activating cold exposure-induced thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue of experimental animals. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1777, 104–112.

- Klein, J.; Fasshauer, M.; Klein, H.H.; Benito, M.; Kahn, C.R. Novel adipocyte lines from brown fat: A model system for the study of differentiation, energy metabolism, and insulin action. Bioessays 2002, 24, 382–388.

- Sveidahl Johansen, O.; Ma, T.; Hansen, J.B.; Markussen, L.K.; Schreiber, R.; Reverte-Salisa, L.; Dong, H.; Christensen, D.P.; Sun, W.; Gnad, T.; et al. Lipolysis drives expression of the constitutively active receptor GPR3 to induce adipose thermogenesis. Cell 2021, 184, 3502–3518.e33.

- Gnad, T.; Scheibler, S.; von Kugelgen, I.; Scheele, C.; Kilic, A.; Glode, A.; Hoffmann, L.S.; Reverte-Salisa, L.; Horn, P.; Mutlu, S.; et al. Adenosine activates brown adipose tissue and recruits beige adipocytes via A2A receptors. Nature 2014, 516, 395–399.

- Lin, J.; Wu, H.; Tarr, P.T.; Zhang, C.Y.; Wu, Z.; Boss, O.; Michael, L.F.; Puigserver, P.; Isotani, E.; Olson, E.N.; et al. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 alpha drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature 2002, 418, 797–801.

- Bartelt, A.; Widenmaier, S.B.; Schlein, C.; Johann, K.; Goncalves, R.L.S.; Eguchi, K.; Fischer, A.W.; Parlakgul, G.; Snyder, N.A.; Nguyen, T.B.; et al. Brown adipose tissue thermogenic adaptation requires Nrf1-mediated proteasomal activity. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 292–303.

- Wittenberg, B.A. Both hypoxia and work are required to enhance expression of myoglobin in skeletal muscle. Focus on “Hypoxia reprograms calcium signaling and regulates myoglobin expression”. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2009, 296, C390–C392.

- Koma, R.; Shibaguchi, T.; Perez Lopez, C.; Oka, T.; Jue, T.; Takakura, H.; Masuda, K. Localization of myoglobin in mitochondria: Implication in regulation of mitochondrial respiration in rat skeletal muscle. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e14769.

- Yamada, T.; Takakura, H.; Jue, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Ishizawa, R.; Furuichi, Y.; Kato, Y.; Iwanaka, N.; Masuda, K. Myoglobin and the regulation of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex IV. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 483–495.

- Wu, Z.D.; Puigserver, P.; Andersson, U.; Zhang, C.Y.; Adelmant, G.; Mootha, V.; Troy, A.; Cinti, S.; Lowell, B.; Scarpulla, R.C.; et al. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 1999, 98, 115–124.

- Puigserver, P.; Wu, Z.; Park, C.W.; Graves, R.; Wright, M.; Spiegelman, B.M. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 1998, 92, 829–839.

- Wicksteed, B.; Dickson, L.M. PKA Differentially Regulates Adipose Depots to Control Energy Expenditure. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 464–466.

- Balkow, A.; Jagow, J.; Haas, B.; Siegel, F.; Kilic, A.; Pfeifer, A. A novel crosstalk between Alk7 and cGMP signaling differentially regulates brown adipocyte function. Mol. Metab. 2015, 4, 576–583.

- Mitschke, M.M.; Hoffmann, L.S.; Gnad, T.; Scholz, D.; Kruithoff, K.; Mayer, P.; Haas, B.; Sassmann, A.; Pfeifer, A.; Kilic, A. Increased cGMP promotes healthy expansion and browning of white adipose tissue. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 1621–1630.

- Nisoli, E.; Clementi, E.; Tonello, C.; Sciorati, C.; Briscini, L.; Carruba, M.O. Effects of nitric oxide on proliferation and differentiation of rat brown adipocytes in primary cultures. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998, 125, 888–894.

- Ceddia, R.P.; Collins, S. A compendium of G-protein-coupled receptors and cyclic nucleotide regulation of adipose tissue metabolism and energy expenditure. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 473–512.

- Movafagh, S.; Crook, S.; Vo, K. Regulation of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1a by Reactive Oxygen Species: New Developments in an Old Debate. J. Cell Biochem. 2015, 116, 696–703.

- Carraway, M.S.; Suliman, H.B.; Jones, W.S.; Chen, C.W.; Babiker, A.; Piantadosi, C.A. Erythropoietin Activates Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Couples Red Cell Mass to Mitochondrial Mass in the Heart. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 1722-U1111.

- Aboouf, M.A.; Guscetti, F.; von Buren, N.; Armbruster, J.; Ademi, H.; Ruetten, M.; Melendez-Rodriguez, F.; Rulicke, T.; Seymer, A.; Jacobs, R.A.; et al. Erythropoietin receptor regulates tumor mitochondrial biogenesis through iNOS and pAKT. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 976961.

- Nisoli, E.; Falcone, S.; Tonello, C.; Cozzi, V.; Palomba, L.; Fiorani, M.; Pisconti, A.; Brunelli, S.; Cardile, A.; Francolini, M.; et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis by NO yields functionally active mitochondria in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 16507–16512.

- Szelenyi, Z. Effect of cold exposure on oxygen tension in brown adipose tissue in the non-cold adapted adult rat. Acta Physiol. Acad. Sci. Hung. 1968, 33, 311–316.

- Xue, Y.; Petrovic, N.; Cao, R.; Larsson, O.; Lim, S.; Chen, S.; Feldmann, H.M.; Liang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Nedergaard, J.; et al. Hypoxia-independent angiogenesis in adipose tissues during cold acclimation. Cell Metab. 2009, 9, 99–109.

- Saha, S.K.; Kuroshima, A. Nitric oxide and thermogenic function of brown adipose tissue in rats. Jpn. J. Physiol. 2000, 50, 337–342.

- Kikuchi-Utsumi, K.; Gao, B.H.; Ohinata, H.; Hashimoto, M.; Yamamoto, N.; Kuroshima, A. Enhanced gene expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in brown adipose tissue during cold exposure. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2002, 282, R623–R626.

- Stone, J.R.; Marletta, M.A. Spectral and kinetic studies on the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase by nitric oxide. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 1093–1099.

- Sebag, S.C.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Qian, Q.W.; Li, M.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Harata, M.; Li, W.X.; Zingman, L.V.; Liu, L.M.; Lira, V.A.; et al. ADH5-mediated NO bioactivity maintains metabolic homeostasis in brown adipose tissue. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 110003.

- Wu, C.; Orozco, C.; Boyer, J.; Leglise, M.; Goodale, J.; Batalov, S.; Hodge, C.L.; Haase, J.; Janes, J.; Huss, J.W.; et al. BioGPS: An extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, R130.

- Nagashima, T.; Ohinata, H.; Kuroshima, A. Involvement of Nitric-Oxide in Noradrenaline-Induced Increase in Blood-Flow through Brown Adipose-Tissue. Life Sci. 1994, 54, 17–25.

- Ono-Moore, K.D.; Olfert, I.M.; Rutkowsky, J.M.; Chintapalli, S.V.; Willis, B.J.; Blackburn, M.L.; Williams, D.K.; O’Reilly, J.; Tolentino, T.; Lloyd, K.C.K.; et al. Metabolic physiology and skeletal muscle phenotypes in male and female myoglobin knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 321, E63–E79.