Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) is the most frequent form of all childhood leukemias, mostly affecting children between 2 and 4 years old. Oral symptoms, such as mouth ulcers, mucositis, xerostomia, Herpes or Candidiasis, gingival enlargement and bleeding, petechiae, erythema, mucosal pallor and atrophic glossitis, are very common symptoms of ALL and can be early signs of the disease.

- pediatric leukemia

- acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- oral health

- oral manifestations

1. Introduction

Leukemia is the most common pediatric cancer in children under 15 years of age, accounting for 30% of all cancers [1]. The survival rate for a child at 3 years is 85% and, at 5 years, 81% [2]. Leukemia is clinically divided into acute and chronic leukemia, and the acute form can be fatal within days. On the basis of histogenicity, it is classified as lymphocytic or myelocytic [3].

Leukemia and its treatment can directly or indirectly affect the oral health of patients and can significantly reduce their quality of life. Different factors increase the risk of developing oral complications, including the patient’s age, gender, nutritional status, type of leukemia, neutrophil count before initiation of treatment, chemotherapy phase, oral health at baseline and oral hygiene [4][5].

Younger patients have a higher rate of post-treatment oral complications than adults. Moreover, the impact of treatments on developing dentition and orofacial growths is high. Oral manifestations and complications include repercussions of hemopathy and adverse effects of treatment. These can be classified as:

-

Primary complications, which occur mainly due to the disease itself; these result from the infiltration of malignant cells into oral structures, such as the gum and bone, and gingival edema or tooth pain due to pulp infiltration.

-

Secondary complications are usually associated with a direct effect of radiation therapy or chemotherapy, such as thrombocytopenia, anemia and granulocytopenia. These include a tendency to bleed or susceptibility to infections.

-

Tertiary complications usually occur due to the complex interactions of therapy and its side effects, such as immunosuppression. They include ulcerations, inflammation of the mucous membranes, osteoradionecrosis, xerostomia, taste alterations, trismus or carious lesions [6].

Oral complications can have a rapid onset upon treatment initiation, with a higher frequency during the first week of chemotherapy. Adverse effects in the oral cavity are frequent, and their signs and severity are diverse [7].

2. Oral Complications in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

2.1. Mucositis

One of the most common side effects occurring during chemotherapy is oral mucositis, also called stomatitis, which has a prevalence of around 40%. It is an inflammation of the mucous membranes, which initially presents as an erythema, often progressing to erosion with loss of the epithelial barrier, followed by ulceration. The most affected areas are the non-keratinized mucous membranes, namely the soft palate, oropharynx, oral and labial mucous membranes, the floor of the mouth, and the ventral and lateral surfaces of the tongue. The patient complains of burning, pain, tingling of the lips and a dry mouth. The pain associated with mucositis can cause difficulty eating, hydrating, and speaking, which can lead to weight loss, anorexia, cachexia and dehydration [8]. Recommended protocols include the use of mouthwash such as normal saline or sodium bicarbonate solutions. Salt and soda mouthwashes are also safe to use [9][10].

2.2. Xerostomia

The majority of childhood cancer survivors experience one or more late effects arising from childhood cancer treatment. Amongst these late effects, survivors may develop salivary gland dysfunction, such as hyposalivation (decreased salivary secretion) and/or xerostomia (oral dryness sensation due to reduced salivation [11]. Xerostomia is the second most common side effect of chemotherapy. Studies have shown that there is a direct relationship between radiation dose and a reduction in saliva [Jensen]. Salivary gland dysfunction is a significant and probably underestimated late effect and may negatively affect general health, as saliva maintains oral health by protecting the oral mucosa and teeth [12][13].

Sedatives, opiates, or antihistamines can also induce xerostomia, but their effects are minor compared to those of radiation therapy. Changes in saliva, both quantitative and qualitative, may appear shortly after induction of antineoplastic therapy. Radiation therapy causes fibrosis and degeneration of the salivary acinar cells, leading to necrosis of the main salivary glands. Saliva becomes more viscous and the proportion of organic matter increases. As a result, its color can change from transparent to opaque, white, or yellow. Its buffering capacity and its pH decrease, which induces a significant increase in the prevalence of infections such as candidiasis, periodontal diseases and caries [12]. The decreased flow and increased viscosity of saliva can cause difficulty chewing, swallowing, or speaking. Lack of saliva also hinders the functioning of the taste buds, causing taste impairment [14][15]. The child should rinse their mouth with sterile water, cold saline or sodium bicarbonate solution as often as possible to keep the tissues of the mouth clean and moist. This helps ensure the removal of thick saliva and food debris and reduces the risk of opportunistic infections. Artificial saliva based on carboxymethylcellulose can also be used, or salivary secretion can be stimulated via simple dietary measures such as eating raw vegetables, chewing sugar-free gums containing xylitol or by using pilocarpine (a cholinergic parasympathomimetic agent used to stimulate salivary flow) [16][17].

2.3. Dysgeusia

The presence of mucositis, as well as treatments, cause dysgeusia (altered taste) which can lead to difficult or even unsuitable nutrition. Some types of chemotherapy drugs can create a bad taste sensation, called the “venous taste phenomenon” due to diffusion of the drug into the oral cavity. Saliva becomes very viscous and unabundant and no longer allows the food bolus to reach the taste buds located in the posterior part of the tongue, which can also cause an alteration of taste. This loss or alteration of taste is often transient because the affected buds regenerate between 2 and 12 months. An alteration in taste can lead to a loss of appetite because children no longer like the taste of certain foods [18].

Management of this symptom requires dietary counseling and parents and the child must be alerted to the importance of good oral hygiene before the treatments [19].

2.4. Gingivitis and Gingival Bleeding

Children with ALL have around 90% prevalence of gingivitis, one of the most common oral manifestations of leukemia. Their risk of developing gingival inflammation is increased compared to that of healthy children [20].

In pediatric ALL, the frequency of gingivitis is increased not only during, but also after treatment, and can evolve, if poorly controlled, to periodontal disease [21].

In addition, gingivitis can manifest from simple bleeding from an inflamed gum to a bruise, hematoma or hemorrhage. Bleeding occurs due to thrombocytopenia (a decrease in platelet count), a consequence of the chemotherapeutic agents, and is aggravated by poor oral hygiene. Prevention is the most effective technique to avoid bleeding: this includes elimination of areas of potential traumatic areas (sharp restorations, fractured teeth) and pre-existing intraoral diseases before chemotherapy. Minor oral bleeding can be controlled with simple pressure using a compress soaked in a hemostatic solution, but major bleeding may require platelet transfusions. Some procedures, such as tooth extractions or periodontal surgery, must be performed when the child has a regular platelet count [22].

2.5. Caries

In children with ALL, an increase in dental caries is usually observed. However, dental caries does not occur because of the disease, or because of radiation therapy or chemotherapy. It is due to alterations in the functioning of the salivary glands, the tendency to have a soft and sweet diet, modification of the oral flora and the inability to maintain oral hygiene due to pain and gingival inflammation [23]. Post-radiation salivary gland damage reduces salivary secretion, makes saliva more acidic, and promotes highly cariogenic oral microflora such as Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus. Impaired dental health due to caries affects cosmesis, functioning and quality of life [24]. The role of the healthcare team is to encourage patients to maintain oral hygiene and inform them of the restrictions on sticky and sweet foods. Many pediatric medicines contain sugar to improve the taste and make them easier to take. It is advisable to avoid these drugs during periods of sleep and to drink water after ingestion [25][26].

2.6. Trismus

Trismus is defined as restricted opening of the mouth and it can be due to dental abscesses, trauma, local anesthesia to the mandible, head and neck radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Thus, trismus associated with icteric appearance, general fatigue loss of appetite and swollen lymph nodes can point to the suspicion of ALL before a diagnosis [27]. The chemotherapeutic agents can cause edema and cell destruction while the radiotherapy-induced fibrotic can cause changes of the masticatory muscles—muscle fibrosis. The limited opening of the mouth can make correct oral hygiene difficult, disrupt eating and swallowing and further hamper the health of the oral cavity [28]. The child should complete regular exercises to stimulate mouth opening and closing and symptoms can be relieved with the administration of anti-inflammatory drugs and muscle relaxants [24].

2.7. Candida and Other Infections

Candidiasis is one of the most common opportunistic infections seen in children with leukemia and is caused primarily by Candida albicans. A dry oral environment favors the appearance of Candida species that stagnate on the oral soft tissues. The clinical signs are small adherent white spots, commonly called thrush, on the oral mucosa, tongue and palate. These small spots have the appearance of “curdled milk” which, when scraped, can be eliminated, and reveal small superficial wounds with slight bleeding. Moreover, there may be erythematous eroded areas, whose appearance is not only due to oral mucosa atrophy, but also due to increased vascularization. The child can also present angular cheilitis, forming a fissure at the labial commissure level. Due to immunosuppression caused by the disease or by the chemotherapeutic agents, various opportunistic infections, other than Candida, may occur [6]. The most observed viral infections are both caused by the Herpesviridae family: Herpes simplex and Varicella-zoster. Herpes simplex clinically manifests in the form of ulcers located at the corners of the mouth, lips, palate and gums. Varicella zoster is seen as multiple blisters, which show a protracted course. It may involve the lungs, central nervous system and liver and is associated with high morbidity. Its management will be almost exclusively palliative. Cytomegalovirus, Adenovirus and Epstein–Barr virus can also appear [20]. In all cases, various topical and systemic antifungal agents can be used: nystatin, clotrimazole and ketoconazole in the first case or fluconazole, itraconazole or ketoconazole in the second situation [29].

2.8. Osteoradionecrosis

Osteoradionecrosis is considered to be one of the most serious oral complications of radiation therapy. Radiation reduces the potential for tissue vascularization by damaging the endothelial lining of the vessels. Blood flow is reduced, thus limiting nutrient supply and defense cells. This leads to hypoxic conditions, resulting in vasculitis and ischemic necrosis of the bone—the most affected tissue, especially if it is subjected to a trauma, such as tooth extraction [30]. The most common site for osteonecrosis after head and neck radiation is the maxilla due to its poor vascularization and presence of teeth. Introduction of preventive oral hygiene and thorough dental assessment before and after radiation may result in a decreased incidence of osteoradionecrosis [31].

2.9. Oral Dysesthesia

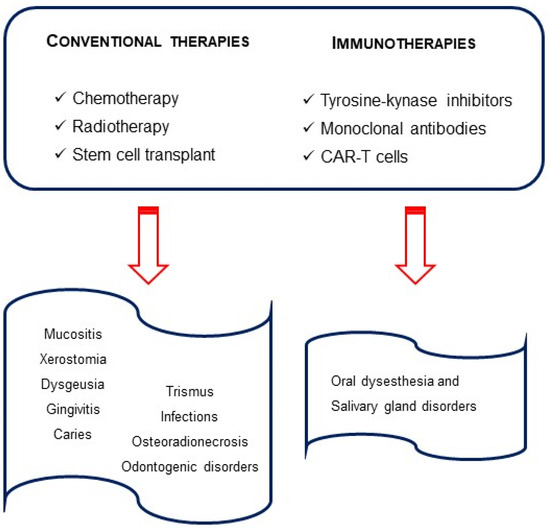

Over the last decade, the prognosis for children with ALL has improved due to the use of precision medicine, identification of distinct subgroups and development of targeted therapies [32]. Immunotherapy, alone or combined with chemotherapy, is used for pediatric refractory/relapsing ALL (R/R ALL) and for Philadelphia-positive (Ph+) children, a rare and poor prognosis subgroup with a defective chromosome—22—resulting from a genetic translocation [33][34]. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), monoclonal antibodies and chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cells are already used, with limited oral manifestations. TKI are associated with oral dysesthesia, specifically oral mucosal sensitivity, a type of oral toxicity not observed in patients receiving conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy: there is a mucosal discomfort without histologic alterations. The child should avoid irritating foods and drinks, use topical analgesics for associated pain and maintain good oral hygiene [35][36].

Blinatumomab, a monoclonal antibody, targeting CD19 antigen and anti-CD19 CAR-T cells are also approved for R/R ALL children with rare oral effects [37] They induce an immune response which can evolve to cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurological toxicity. The latter is associated with speaking and swallowing problems, difficulty with facial movements and xerostomia. Thus, these are all transient conditions [38][39]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapies for children with ALL can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Therapies in pediatric acute lymphocytic leukemia and oral outcomes.

Children with ALL frequently experience treatment-related pain. Some of the complications mentioned before, like mucositis and xerostomia, can also lead to constant jaw pain and dental sensitivity. This is often underestimated and undertreated in children, so early diagnosis will contribute to better decisions of the therapeutic strategy to be applied [26].

2.10. Dental Developmental Disorders

Dental developmental disorders are prevalent among children with ALL. Diagnosis before the age of 3 and dose-dependent alkylating agent therapy are the main risk factors for dental alterations [11]. Thus, there is strong evidence that dental abnormalities are more prevalent in children who have received chemotherapy compared to healthy children.

Disturbed odontogenesis has been demonstrated after the administration of numerous chemotherapeutic agents by interfering with the mitotic cycle of cancer cells [40]. The abnormalities are caused by the type, intensity, frequency of the treatment and age of the patients at ALL diagnosis. Thus, it has important consequences for the children’s dental development. The effects of chemo and radiotherapy on the orofacial area depend on the age of the patient at the beginning of treatment and on the radiation dose [41][42].

Anti-neoplastic therapies can lead to enamel dysplasias (discoloration and hypoplasia), as well as to radicular anomalies such as resorbed or tapered roots; delayed root formation; early apical closure; dental anomalies including V-shaped roots, delayed dental development or dental impaction; qne dental shape anomalies (microdontia, macrodontia, taurodontia), and dental numbers anomalies can also be found (hypodontia, agenesia, supernumerary teeth) [11][13][41][42][43]. Furthermore, after ALL, children are at a higher risk of developing dental caries, lesions of the enamel, discoloration of teeth or even early tooth loss, thus requiring the use of dental prosthesis [44].

This wide range of variations in dental structures is recognized as a side effect of childhood cancer therapy in long-term survivors of pediatric malignancies and may affect their quality of life [45].

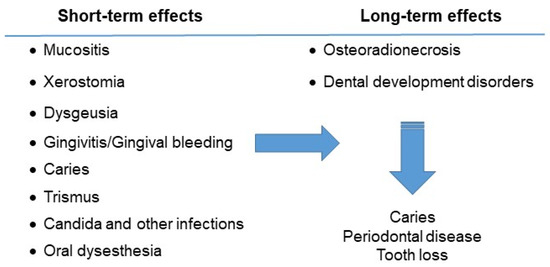

The oral effects of the disease and drugs used for the treatment can be divided according to their duration. Most of the complications are short term and last only until the end of the therapeutic treatment. Others are considered long-term adverse effects, especially when the child’s odontogenesis is affected (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Oral complications of the child with acute lymphocytic leukemia.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/hematolrep15030051

References

- Madhusoodhan, P.P.; Carroll, W.L.; Bhatla, T. Progress and Prospects in Pediatric Leukemia. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2016, 46, 229–241.

- Fathi, A.; Mirzarahimi, M.; Farajkhah, H. Réponse à un schéma chimiothérapeutique administré à des enfants atteints de LAL à cellules pré-B à risque élevé selon le protocole COG. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2021, 31, 334–338.

- Lim, H.-C.; Kim, C.-S. Oral signs of acute leukemia for early detection. J. Periodontal Implant. Sci. 2014, 44, 293–299.

- Babu, K.L.G.; Mathew, J.; Doddamani, G.M.; Narasimhaiah, J.K.; Naik, L.R.K. Oral health of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A review. J. Orofac. Sci. 2016, 8, 3.

- Mathur, V.P.; Kalra, G.; Dhillon, J.K. Oral health in children with leukemia. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2012, 18, 12–18.

- Wang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Yang, X.; Que, J.; Du, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, J. Oral Health, Caries Risk Profiles, and Oral Microbiome of Pediatric Patients with Leukemia Submitted to Chemotherapy. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6637503.

- Lula, E.C.d.O.; Lula, C.E.d.O.; Alves, C.M.C.; Lopes, F.F.; Pereira, A.L.A. Chemotherapy-induced oral complications in leukemic patients. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2007, 71, 1681–1685.

- Valéra, M.-C.; Noirrit-Esclassan, E.; Pasquet, M.; Vaysse, F. Oral complications and dental care in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2015, 44, 483–489.

- Brown, T.J.; Gupta, A. Management of Cancer Therapy–Associated Oral Mucositis. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015, 16, 103–109.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD). Dental Management of Pediatric Patients Receiving Immunosuppressive Therapy and/or Head and Neck Radiation; The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry: Chicago, IL, USA, 2022; pp. 507–516.

- Stolze, J.; Vlaanderen, K.C.E.; Holtbach, F.C.E.D.; Teepen, J.C.; Kremer, L.C.M.; Loonen, J.J.; Broeder, E.v.D.-D.; Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.v.D.; van der Pal, H.J.H.; Versluys, B.; et al. Long-Term Effects of Childhood Cancer Treatment on Dentition and Oral Health: A Dentist Survey Study from the DCCSS LATER 2 Study. Cancers 2021, 13, 5264.

- Jensen, S.; Pedersen, A.; Reibel, J.; Nauntofte, B. Xerostomia and hypofunction of the salivary glands in cancer therapy. Support. Care Cancer 2003, 11, 207–225.

- Stolze, J.; Teepen, J.C.; Raber-Durlacher, J.E.; Loonen, J.J.; Kok, J.L.; Tissing, W.J.E.; de Vries, A.C.H.; Neggers, S.J.C.M.M.; Broeder, E.v.D.-D.; Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.v.D.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Hyposalivation and Xerostomia in Childhood Cancer Survivors Following Different Treatment Modalities—A Dutch Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Late Effects 2 Clinical Study (DCCSS LATER 2). Cancers 2022, 14, 3379.

- Jensen, S.B.; Vissink, A.; Limesand, K.H.; E Reyland, M. Salivary Gland Hypofunction and Xerostomia in Head and Neck Radiation Patients. J. Natl. Cancer Inst.–Monogr. 2019, 53, 95–106.

- Silva, I.M.; Donaduzzi, L.C.; Perini, C.C.; Couto, S.A.; Werneck, R.I.; de Araújo, M.R.; Kurahashi, M.; Johann, A.C.; Azevedo-Alanis, L.R.; Vieira, A.R.; et al. Association of xerostomia and taste alterations of patients receiving antineoplastic chemotherapy: A cause for nutritional concern. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 43, 532–535.

- Villa, A.; Connell, C.L.; Abati, S. Diagnosis and management of xerostomia and hyposalivation. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2014, 11, 45–51.

- Johnson, J.T.; Ferretti, G.A.; Nethery, W.J.; Valdez, I.H.; Fox, P.C.; Ng, D.; Muscoplat, C.C.; Gallagher, S.C. Oral pilocarpine for post-irradiation xerostomia in patients with head and neck cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 390–395.

- Brink, M.v.D.; Ijpma, I.; van Belkom, B.; Fiocco, M.; Havermans, R.C.; Tissing, W.J.E. Smell and taste function in childhood cancer patients: A feasibility study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 1619–1628.

- Munankarmi, D. Management of Dysgeusia related to Cancer. J. Lumbini Med. Coll. 2017, 5, 10.

- Ponce-Torres, E.; Ruíz-Rodríguez, M.d.S.; Alejo-González, F.; Hernández-Sierra, J.F.; de Pozos-Guillén, A. Oral Manifestations in Pediatric Patients Receiving Chemotherapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2010, 34, 275–279.

- Kaskova, L.F.; Yanko, N.V.; Vashchenko, I.Y. Gingival health in children in the different phases of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr. Issues Pharm. Med. Sci. 2019, 32, 134–137.

- Francisconi, C.F.; Caldas, R.J.; Martins, L.J.O.; Rubira, C.M.F.; Santos, P.S.d.S. Leukemic Oral Manifestations and their Management. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 17, 911–915.

- Shayani, A.; Aravena, P.C.; Rodríguez-Salinas, C.; Escobar-Silva, P.; Diocares-Monsálvez, Y.; Angulo-Gutiérrez, C.; Rivera, C. Chemotherapy as a risk factor for caries and gingivitis in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2021, 32, 538–545.

- Gawade, P.L.; Hudson, M.M.; Kaste, S.C.; Neglia, J.P.; Constine, L.S.; Robison, L.L.; Ness, K.K. A systematic review of dental late effects in survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 407–416.

- Al Humaid, J. Sweetener content and cariogenic potential of pediatric oral medications: A literature. Int. J. Health Sci. 2018, 12, 75–82.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD). Guideline on Dental Management of Pediatric Patients Receiving Chemotherapy, Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, and/or Radiation Therapy; American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013.

- Katz, J.; Peretz, B. Trismus in a 6 year old child: A manifestation of leukemia? J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2002, 26, 337–339.

- Satheeshkumar, P.; Mohan, M.P.; Jacob, J. Restricted mouth opening and trismus in oral oncology. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2014, 117, 709–715.

- Yigit, M.; Bilir, A.; Yüksek, S.K.; Kaçar, D.; Özbek, N.Y.; Yarali, H.N. Antifungal Therapy in Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Pediatr. Hematol./Oncol. 2022, 44, e653–e657.

- Brivio, E.; Cossio, A.; Borra, D.; Silvestri, D.; Prunotto, G.; Colombini, A.; Verna, M.; Rizzari, C.; Biondi, A.; Conter, V.; et al. Osteonecrosis in paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: Incidence, risk factors, radiological patterns and evolution in a single-centre cohort. Br. J. Haematol. 2022, 197, 602–608.

- Kuhlen, M.; Kunstreich, M.; Gökbuget, N. Osteonecrosis in Adults with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: An Unmet Clinical Need. Hemasphere 2021, 5, e544.

- Pui, C.-H. Precision medicine in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front. Med. 2020, 14, 689–700.

- Lejman, M.; Kuśmierczuk, K.; Bednarz, K.; Ostapińska, K.; Zawitkowska, J. Targeted Therapy in the Treatment of Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia—Therapy and Toxicity Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9827.

- Ribera, J.-M.; Chiaretti, S. Modern Management Options for Ph+ ALL. Cancers 2022, 14, 4554.

- Vigarios, E.; Epstein, J.B.; Sibaud, V. Oral mucosal changes induced by anticancer targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 1713–1739.

- Partanen, M.; Alberts, N.M.; Conklin, H.M.; Krull, K.R.; Pui, C.-H.; Anghelescu, D.A.; Jacola, L.M. Neuropathic pain and neurocognitive functioning in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pain 2022, 163, 1070–1077.

- Jasinski, S.; Reyes, F.A.D.L.; Yametti, G.C.; Pierro, J.; Raetz, E.; Carroll, W.L. Immunotherapy in Pediatric B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Advances and Ongoing Challenges. Pediatr. Drugs 2020, 22, 485–499.

- Lv, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, S. Immunotherapy for Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 921894.

- Malczewska, M.; Kośmider, K.; Bednarz, K.; Ostapińska, K.; Lejman, M.; Zawitkowska, J. Recent Advances in Treatment Options for Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancers 2022, 14, 2021.

- Jodłowska, A.; Postek-Stefańska, L. Systemic Anticancer Therapy Details and Dental Adverse Effects in Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6936.

- Lupi, S.M.; Baena, A.R.Y.; Cervino, G.; Todaro, C.; Rizzo, S. Long-Term Effects of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treatment on the Oral System in a Pediatric Patient. Open Dent. J. 2018, 12, 230–237.

- Minicucci, E.M.; Lopes, L.F.; Crocci, A.J. Dental abnormalities in children after chemotherapy treatment for acute lymphoid leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2003, 27, 45–50.

- Lauritano, D.; Petruzzi, M. Decayed, missing and filled teeth index and dental anomalies in long-term survivors leukaemic children: A prospective controlled study. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2012, 17, e977–e980.

- Proc, P.; Szczepańska, J.; Skiba, A.; Zubowska, M.; Fendler, W.; Młynarski, W. Dental Anomalies as Late Adverse Effect among Young Children Treated for Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 48, 658–667.

- Çetiner, D.; Çetiner, S.; Uraz, A.; Alpaslan, G.H.; Alpaslan, C.; Memikoğlu, T.U.T.; Karadeniz, C. Oral and dental alterations and growth disruption following chemotherapy in long-term survivors of childhood malignancies. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1891–1899.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!