Thanks so much for your check. We sincerely hope you may create this entry, since you are the expert in this academic research. You can click the “submit” button to upload it and revise it. We will help you layout after you submit it. Moreover, we will link your article at the entry, and more scholars and students can benefit from it. (You can remove this note when submitting.)

1. Introduction

High academic standards are essential to a university bringing out high-quality research and teaching outcomes, leading to delivery of high-quality graduates. The purpose of maintaining high academic standards can be manifold—not only to meet standards set by the national education standard governing body or professional, statutory and regulatory bodies (PSBR) but to provide confidence to convey that the quality of education meets the current and future competencies and needs of the wider society. According to Anderson et al. (2000), quality assurance is “the means by which an institution is able to confirm that the standards (of teaching and learning), set by the institution itself or other awarding bodies, are being maintained and enhanced” [

1]. Consequently, quality assurance (QA) has an important role in monitoring an institution’s own processes and performance of achievements, whereby it serves in a consistent application and continuous improvement of processes and reduces the scope for variability. Furthermore, the concepts of quality and standards are interconnected and it is difficult to discuss standards without discussing quality, and vice versa. Quality in higher education is considered in a broad range of inter-related activities, such as curriculum, teaching, student learning, assessment, student experience, student selectivity and research [

2]. Because of this multifaceted nature of quality, QA in higher education institutions (HEIs) adopts different approaches and procedures. The standards-based approach assesses universities against a set of pre-determined standards, which are often externally developed. The fit-for-purpose approach is used to analyze performance against the internally set goals and missions of the HEI itself. The minimum requirement approach is used to ensure universities fulfil minimum standards, often adopted for compliance purposes [

3].

One of the main aims of quality assurance is to identify whether a particular institution fulfils the baseline of the national and/or quality standards set for the higher education institution operations [

4,

5]. Based on the positive results from quality audits that a higher education institution received, they provide the institution with an “authorization” to continue its work. The results of the auditing can be applied, for example, in the marketing of the programs, particularly to attract the best students, as well as in preparing applications for research and development funding. It also allows staff to compare their own university to others on a qualitative scale [

6].

Quality assurance procedures can serve two major purposes: accountability and improvement. Quality procedures for accountability are based on criteria aimed at strengthening external insight and control, set by external authorities. Quality assurance for accountability purposes indicates the use of a summative approach, with the possibility of taking corrective actions by an external authority, if necessary. Quality assurance for improvement purposes has a formative approach—the focus is on improving quality instead of control [

7].

Universities, being public institutions, have a major responsibility to maintain quality and standards. However, periodic external reviews by an independent agency will provide further credibility to the public and satisfy social accountability. Thus, external quality assurance is considered as an effective way of safeguarding the quality of delivery and standards of awards in higher education while facilitating quality improvement [

8]. There can be various agencies inspecting quality in HEIs, such as government bodies (ministries or federal agencies) or autonomous agencies established either by the government or the HEIs themselves [

7].

Institutional review analyses and tests the effectiveness of an institution’s processes, for managing and assuring the quality of academic activities undertaken by the HEI. It evaluates the extent to which internal quality assurance schemes can be relied upon to maintain the quality of provision of educational programs over time. The overall purpose of an institutional review is to achieve accountability for quality and standards by using a peer review process to promote the sharing of good practices and to facilitate continuous improvement. On the other hand, a Subject/Program review assesses the quality of the student learning experience at the programme level [

9].

The designs of higher education quality assurance systems in various countries are influenced by the higher education systems, traditional culture and social backgrounds in that country. Having clearly defined and harmonious relationships of responsibility, rights and interests between various stakeholders in quality assurance is the pre-condition for quality assurance mechanisms to effectively run in these countries [

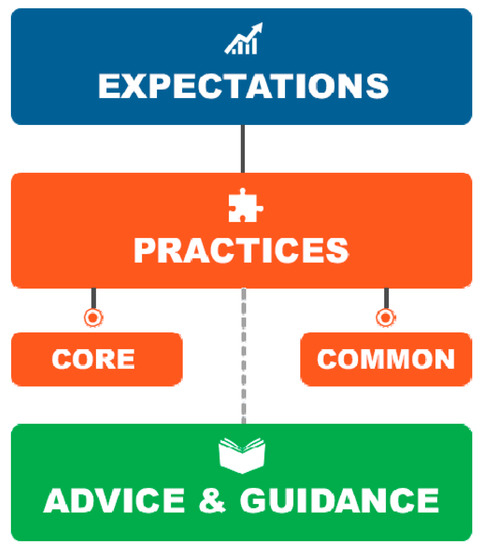

10]. For example, in the UK, the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) has developed a quality code for higher education, where it enables universities and colleges to understand the expectations of them (see the key elements in ). Particularly, it helps HEIs to identify quality code as a reference point to protect public and student interests, championing UK higher education’s world-leading reputation for quality [

11].

Figure 1. Elements of the quality code as highlighted by the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA), UK [

11].

Higher education policies related to quality assurance are instigated in many countries to ensure the provision of high-quality education, university accountability and transparency in using public funding and meeting the needs of the diverse stakeholders [

12]. Every university or higher education institution is dedicated to a policy of self-evaluation of all its programs, procedures, services and administrative mechanisms on a regular basis, which encompasses a quality self-assessment. This is because the responsibility for quality and standards in higher education primarily exists within the university itself, rather than outside of it [

9].

The novel coronavirus, known as COVID-19, has caused massive disruption to the daily life of humans around the world. On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 to be a global pandemic, showing how widely the virus has spread across the world since its first emergence in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 [

13]. For an indefinite period, COVID-19 is continuing to raise health concerns and this will continue to challenge many aspects in international higher education as well. As such, the scale of the impact of this pandemic indicates that many HEIs need to adapt and mitigate the consequences.

In what may be termed as a “forced stop”, most countries followed a “lockdown” procedure to curtail human movement. Consequently, all face-to-face activities were severely restricted, and universities have had to close down abruptly to ensure that the health and safety of their staff and students are not compromised. According to UNESCO, it is estimated that 1.58 billion learners are off schools, which represents 91.3% of total enrolled learners in the world [

14]. A survey on international student recruitment has also shown that an overwhelming number of prospective students had been impacted by this crisis, causing a change their plans as a result. Most of the respondents have primarily chosen to defer their studies until the following year [

15].

Many universities use the conventional education system that requires the physical presence of students and teachers, and therefore, many universities were not fully prepared to face a crisis of such magnitude. Many students have raised issues about travel restrictions, university closure, cancelling of flights, problems in obtaining scholarship interviews, economic collapses, visa applications or language tests, as well exam postponements or cancellations apart from the apparent health concerns [

16]. So, at times of crisis, universities must have risk management strategies to maintain their quality and accountability. This paper explores the challenges that universities have encountered as a result of the pandemic and discusses their approaches to retain high academic standards and quality assurance procedures without compromising them.

2. Academic Integrity

The International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI) defines Academic Integrity as ‘a commitment, even in the face of adversity, to six fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage [

31]. From these values flow principles of behaviour that enable academic communities to translate ideals to action’. As such, academic integrity is a concept which, on one hand, protects the quality of the student learning experience, to value their academic achievements, and, on the other hand, provides assurance and reputation for the higher education institutions for the programs offered. Hence, it can be understood that sustaining academic integrity has a two-way approach: (1) prevent and act against academic misconduct and (2) popularize good practices [

31]. It is important to note that academic integrity must be maintained at all times, irrespective of global pandemics; the only thing is that the measures to secure it will depend on how the learning outcomes of a programme are assessed by the higher education institution. It is the responsibility of the higher education institution to remind students of the policies already put in place on academic integrity and highlight that these continue to apply even in the current circumstances.

As a consequence of COVID-19, higher education institutions have had to adjust their assessment practices to suit online delivery. In doing so, it must be ensured that these practices are robust, safeguarding against academic misconduct but equally ensuring fairness for students who have had to sit for university assessments during challenging circumstances.

All stakeholders of the academic community (e.g., academia, students, professional services, administration and the management) need to be aware of policies, procedures, regulations, expectations and sanctions, as well as to be supported to understand what academic practices are considered as acceptable or not.

Furthermore, it is essential to ensure that students are aware of the potential consequences if they are caught cheating. In order to convey this effectively, discussing academic misconduct with students and the risks involved will help them understand the long-term and ethical benefits of the genuineness of their work [

32]. Some further actions involve developing internal networks of academic integrity support or submitting an “Academic Integrity Honesty Statement” or equivalent for students before they sit for online exams to make them personally responsible by putting their signature [

33].

2.1. How to Uphold Academic Integrity in Online Delivery: Course/Lab/Assessment Design

In the UK, for example, as suggested by QAA guidelines/National Forum Enhancement Theme, some actions include preparing students with skills, such as academic writing and referencing skills, necessary to succeed in their assessments; frameworks and structures to keep students on track; moderation of peer learning forums and other student-friendly channels to communicate university support; proper dealing with cases of misconduct; consider accessibility to all students (hardware/software requirements, assessment submission processes, logistical issues, etc.) in using technology and engaging with online assessment tools [

34].

2.2. Use of Technology: Plagiarism Checker, Virtual Invigilation

The use of technology to curb this issue is seen as a potential solution in the ever-evolving methods of compromising academic honesty and integrity. Apart from blocking access to “essay mills” and disrupting their advertising tactics on university IT systems, modifying online assessments is also important to discourage the students from cheating [

35].

Online proctoring services, for example (which use a combination of microphone, webcam, speakers, screen-sharing, etc.), can be used to supervise remote exams. For these purposes, a specialist online testing service (such as ProctorU) can be utilized, which operates under multi-jurisdictional privacy and security regulations while ensuring that student privacy and security is safeguarded during online invigilation [

36]. It is worth mentioning, here, the challenges related to the large-scale move to online assessments, e.g., cost, capability, risks, etc.

In the context of essays and other written assignments, modifying assessments to allow students to demonstrate their skills (combining straight answer questions with brief explanations or reasoning) can also help them to develop deep learning abilities [

35]. Use of software (plagiarism checking, text matching, stylometric and linguistic analytics, etc.) is also a recommended technique [

29]. If written assignments can be completed in a student’s own time, students can be provided with early drafts or “checkpoints” as these assignments are more prone to cheating [

34]. This “checkpoints” or (“advanced drafts”) method can be used for assessing group activities as well. Additionally, calling students after submission of assignments for a brief online ‘viva’ to check their understanding and authenticity of the work and comparing previous student performances to what has been obtained via online assessments to determine whether it keeps with expectations can also help in maintaining the integrity of written essays [

25]. For individual or group performances (performance arts such as music, dance, drama, etc.), alternative assessments, such as video/audio recordings, recitals, online portfolios and virtual studios, and written assessments, such as essays, reflective blogs, etc., can be used [

37]. However, these assessments must, in one way, be achievable for students at home while also being assessable for home-working teachers/markers.

3. Safety

The COVID-19 situation has forced HEIs to amend existing processes in order to open campuses for students and staff following public health advice and government rules on social distancing. This is of particular importance for programs involving heavy elements of practical work. This academic year, many universities have adopted a blended approach that combines both online and on-campus teaching. Usually, on-campus teaching activities involve tutorials and practicals, while large-scale lectures are being delivered using online technology. Another interesting approach is to use a dual-mode system that delivers material simultaneously for on-campus face-to-face students and off-campus online students. The Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry Department at Aston University has recently adopted dual-mode teaching for practicals and workshops, providing students with additional flexibility to switch between the face-to-face and online modes but also allowing adequate social distancing on campus.

It is clear that university programs have been adapting their teaching settings and contexts due to the safety requirements imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Recently, Universities UK has published a list of principles for individual universities to deliver their teaching safely and in line with guidance from governments, public health advice and health and safety legislation [

38]. These include health, safety and wellbeing, changes to university layout and infrastructure, reviews of teaching, learning and assessment, review of the welfare and mental health needs of students and staff, support for international students and staff, review of cleaning protocols and risk assessments as well as engagement with the wider community, such as trade unions, councils and other community groups.

To conclude, health guidelines have become a new part of the teaching, learning and assessment planning, placing themselves as a central part of quality assurance in HEIs.