Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Biotechnology & Applied Microbiology

Actinomycetes inhabit both terrestrial and marine ecosystems and are highly proficient in producing a wide range of natural products with diverse biological functions, including antitumor, immunosuppressive, antimicrobial, and antiviral activities.

- actinomycetes

- bioactive metabolites

- biodiversity

- genome mining

1. Introduction

Actinomycetes are generally recognised as filamentous Gram-positive bacteria in the order Actinomycetales [1]. Typical actinomycete colonies show distinct powdery characteristics containing filamentous mycelium-like fungi and spore-forming properties (e.g., genera Streptomyces, Microbispora, Streptosporangium, and Microbispora). The genus Streptomyces stands out as the most dominant and well-known actinomycetes. These are primarily aerobic bacteria with a notable high G + C content in their DNA, approximately ranging from 60% to 78% [1,2]. The Actinomycetales members show extensive diversity in their morphology, physiology, and metabolic capabilities. Rare or non-streptomycete actinomycetes are a group of actinomycete bacteria that are rarely isolated from the environment compared to dominant Streptomyces. Rare actinomycetes include Actinomadura, Actinoplanes, Actinokineospora, Actinosynema, Kineosporia, Planobispora, Nocardia, Thermomonospora, Saccharothrix, and Saccharopolyspora [3]. Rare actinomycetes have attracted attention due to their low frequency in isolation and the potential discovery of new natural bioactive compounds such as macrolide antibiotics [4,5].

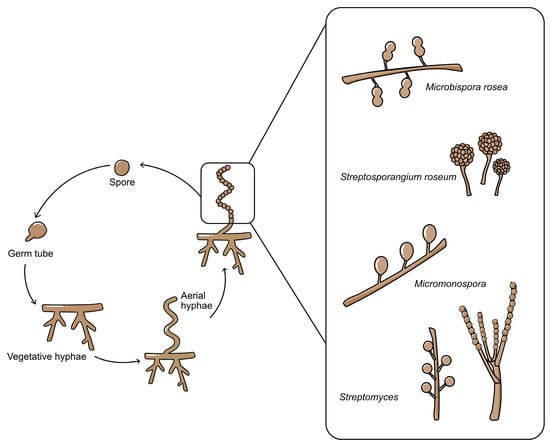

Most actinomycetes are aerobic, saprophytic microorganisms with complex life cycles (Figure 1) except for unicellular Corynebacterium and Mycobacterium [6]. Actinomycetes have well-developed radial mycelium dividing into the substrate and aerial mycelium during their life cycle. Substrate mycelium is developed in the media to assimilate nutrients, and then aerial mycelium is developed afterwards. However, when actinomycetes grow in an impoverished environment, the hypha becomes coiled and develops a septum. After the septum develops, conidiospores form within the hyphae. Except for Streptomyces with its long-chain spores, other genera have distinguishable characteristics, such as Micromonospora (single non-motile spore), Microbispora (two spores in a chain), and Streptosporagium (bearing sporangium as spore vesicle) [1]. Spores will be released into the environment and germinate when favourable condition is achieved. In the germination step, the spore will protrude germ tubes then, germ tubes reach the vegetative growth stage, and the cycle is repeated [2,7].

Figure 1. The life cycle of actinomycetes, starting from conidiospores until sporulation. The various types of conidiospores are shown in the expanded box.

Actinomycetes play an important role in biotechnology and pharmacology because they can produce various secondary metabolites and other useful compounds such as antibiotics, antitumor agents, immunosuppressive agents, and nutritional materials. Therefore, their secondary metabolites and diversity make actinomycetes an important group of key compound producers.

2. Ecology of Actinomycetes

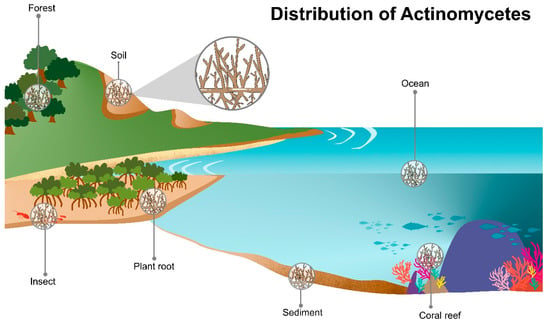

Actinomycetes are widely distributed in various ecosystems and habitats including soil and marine habitats, freshwater, animals, plants, insects, and fertilizer (Figure 2) [8,9]. They are free-living, saprophytes in an environment such as soil pore [8] or living as endophytes in plants [10]. The actinomycete members include inhabitants of soil or aquatic environments (e.g., Streptomyces, Micromonospora, Rhodococcus, and Salinispora species); plant symbionts (e.g., Frankia spp.); and insect, plant, or animal pathogens (e.g., Corynebacterium, Mycobacterium or Nocardia species) [1,11,12]. They also present in extreme environments especially the psychrophilic area, for example, Antarctica terra and desert soil [13,14,15].

Figure 2. Diversity of actinomycetes habitats. Actinomycetes are predominantly found in various ecological habitats e.g., marine ecosystems (of water bodies, coral reefs, seawater, mangrove forest), and terrestrial ecosystems (soil and plants, and insects).

2.1. Soil Actinomycetes

Actinomycetes grow as hyphae-like fungi responsible for the characteristically “earthy” smell of freshly turned healthy soil. The actinomycete population is largest in the surface layer of soils and gradually decreases with depth because of their need for oxygen [16,17]. Their estimated values range from 104 to 108 cells per gram of soil. They are sensitive to acidity/low pH (optimum pH range is 6.5–8.0) and waterlogged soil conditions. These microorganisms are primarily mesophilic, thriving in temperatures between 25 °C and 30 °C. Actinomycetes play a crucial ecological role as saprophytes, actively participating in various biological processes such as organic matter recycling, bioremediation, and promoting plant growth.

Plant growth-promoting actinomycetes use both direct (e.g., producing plant hormones) and indirect (e.g., inhibitory to plant pathogens) mechanisms to influence plant growth and protection [18,19,20,21]. They impact the process of plant biomass decomposition [22] and the microbiome around the rhizosphere [20]. They are also found in salty soil samples [23]. Ahmed et al. [24] explored the saline soil microbiome for its native structure and novel genetic elements involved in osmoadaptation. Their 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis indicated the dominance of halophilic/halotolerant phylotypes affiliated with Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota, Gemmatimonadota, Bacteroidota, Bacillota, and Acidobacteriota. Their microbiome analysis revealed that the abundance of Actinomycetota among the other phyla was 21%.

2.2. Endophytic Actinomycetes

Endophytic actinomycetes that reside within the interior tissues of healthy plants without adversely affecting the host plant are an excellent source of potential new bioactive compounds [10,12]. Endophytic strains have been isolated from diverse plants, such as crop plants, medicinal plants, halophytes, and some woody tree species [10,25]. Examples of endophytic actinomycetes include Actinoallomurus, Actinoplanes, Allonocardiopsis, Amycolatopsis, Blastococcus, Glycomyces, Kibdelosporangium, Micrococcus, Micromonospora, Modestobacter, Nocardia, Nocardioides, Nonomuraea, Plantactinospora, Pseudonocardia, Pseudonocardia, Rothia, Saccharopolyspora, Solirubrobacter, Sphaerisporangium, Streptomyces, Streptosporangium, Wangella, and Xiangella [12].

A 16S rRNA analysis by Janso and Carter [26] categorised 113 isolated actinomycetes from 256 tissue samples (e.g., leaves, roots, and stems) collected from 113 plants. They found six families: Streptosporangiaceae (40%), Streptomycetaceae (27%), Thermomonosporaceae (16%), Micromonosporaceae (8%), Pseudonocardiaceae (8%), and Actinosynnemataceae (2%). Their findings indicate that rare actinomycetes (non-Streptomyces) predominate in plant samples. In general, the appearance of isolated, rare actinomycetes from soil samples will be either inhibited or hindered by fast-growing Streptomyces strains [27]. However, this is not the case in plant roots where the ratio of Streptomyces is low. Therefore, plant roots are an excellent potential source of rare actinomycetes and, probably, new secondary metabolites.

2.3. Actinomycetes in Compost

During the composting process, microorganisms (bacteria, actinomycetes, and fungi) are vital for organic matter degradation to produce carbon dioxide, water, heat, and humus and the relatively stable organic product as byproducts [28]. Composting generally proceeds through three main phases: (i) the mesophilic phase, (ii) the thermophilic phase, and, finally, (iii) the cooling and maturation phase. Different microbial consortia play a role during each composting phase [29]. Early decomposition is performed by mesophilic microbes, which rapidly break down soluble, readily degradable compounds. The accumulative heat causes the compost temperature to rise rapidly. As the temperature increases > 40 °C, the mesophilic microorganisms are less active and are replaced by thermophilic microbes. During the thermophilic phase, high temperatures accelerate the degradation of organic molecules such as proteins, fats, and complex carbohydrates in plant-like cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [30]. As these complex compounds are used up, the temperature of the compost gradually decreases, and mesophilic microorganisms once again predominate the final phase of ‘curing’ or maturation of the remaining organic matter.

Actinomycetes are typically present in the compost, particularly in the thermophilic and curing stages [31,32]. Thermophilic actinomycetes are well-known components of composts’ microflora and play an important role in habitats where organic matter decomposition occurs at elevated temperatures and under aerobic conditions (e.g., improperly stored hay, cereal grains, manure, straw, and various composts). Thermophilic actinomycetes include various genera, such as Saccharomonospora, Saccharopolyspora, Streptomyces, Thermoactinomyces, Thermobifida, and Thermomonospora.

2.4. Marine Actinomycetes

Marine habitats are a rich source of diverse and mostly uncharacterised actinomycetes. Marine habitats include coastal, deep-sea sediment, seawater, and mangrove forests. Mangrove forests are highly dynamic ecosystems that cover 75% of the world’s tropical climate, and the diversity of mangrove organisms remains less unexplored. Mangrove forests are a unique environment because they fluctuate with salinity and tidal gradients that favour their microorganisms to produce unusual metabolites [33].

Reports on marine actinomycetes have emerged since the late 19th century. Since 1980, biotechnology initially provided direction to study marine microorganisms for various applications such as drug development [34]. This study was ongoing until 1984 and used various techniques, identifying the first marine actinomycete, Rhodococcus marinonascens [11]. In 2005, the first seawater-obligate marine actinomycetes genus, Salinispora, was described. Salinispora tropica and Salinispora arenicola are novel species belonging to the family Micromonosporaceae. This genus required seawater for its growth [35]. Fencial and Jensen [36] detected novel secondary metabolites produced by Salinispora, leading to a further search for new groups of marine actinomycetes [34]. Studied marine actinomycete genera include Dietzia, Rhodococcus, Streptomyces, Salinispora, and Micromonospora. Microbiomes or traditional bacterial enumeration have been studied in marine ecosystems, including seawater [37], coral reefs [38,39,40], and mangroves [36,41,42,43]. There are various groups of microorganisms in mangrove sediments, such as Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota, and fungi. Both Streptomyces and Micromonospora from marine habitats are good candidates for isolating potent growth-inhibiting compounds and antitumor agents. Its secondary metabolites show diverse bioactivities, such as antifungal, antitumor, and antibacterial [44]. Marine actinomycetes are one potential marine organism that can produce efficient anticancer agents such as salinosporamide A (S. tropica), actinomycin D (Streptomyces parvulus), mitomycin C (Streptomyces caespitosus), and Rakicidin D (Streptomyces sp. MWW064) [45,46].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules28155915

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!