Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is highly prevalent in older adults, yet its management remains challenging. Treatment choices are made complex by the frailty burden of older patients, a high prevalence of comorbidities and body composition abnormalities (e.g., sarcopenia), the complexity of coronary anatomy, and the frequent presence of multivessel disease, as well as the coexistence of major ischemic and bleeding risk factors.

- aged

- frailty

- coronary artery disease

- ischemia

- hemorrhage

- multimorbidity

- antithrombotic agents

1. Introduction

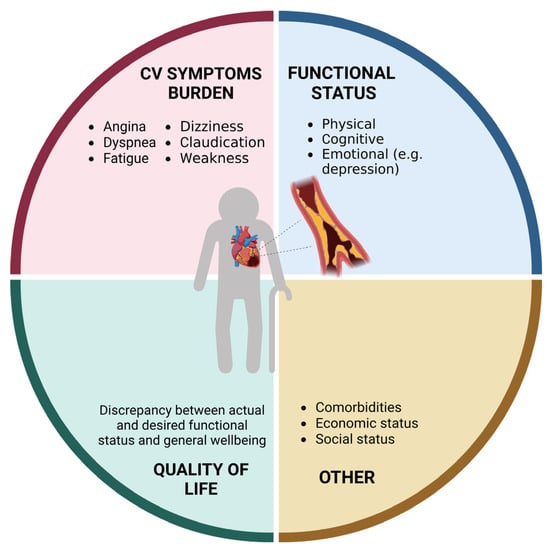

Coronary heart disease (CAD) is the leading cause of mortality worldwide [1]. Due to evolution in medical sciences and technology, life expectancy has increased over the last century. This has caused a “boomerang effect” in terms of prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD), with more than 60% of all cardiovascular deaths occurring in people aged 75 years and older [1]. Acute coronary syndromes (ACSs) impose a significant health burden (Figure 1) and are the most frequent cause of death in older adults. Aging, per se, increases CVD risk via several pathophysiological mechanisms, such as increased arterial and ventricular stiffness, altered blood pressure control, increased oxidative stress and inflammation levels, hypercholesterolemia, and impaired glucose metabolism [2]. Notwithstanding, older adults are still underrepresented in clinical trials testing therapeutics for CVD [3], and conventional endpoints may not be adequate for addressing the medical needs and expectations of older individuals [4]. The lack of robust evidence and the frequent presence of multimorbidity, polypharmacy, frailty, body composition abnormalities, and geriatric syndromes make the management of older patients with CVD highly complex.

Figure 1. Domains affected by coronary heart disease in older adults (created with Biorender.com, accessed on 30 June 2023).

2. Optimal Strategy during the Acute Phase of Coronary Syndromes: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery, or Medical Treatment?

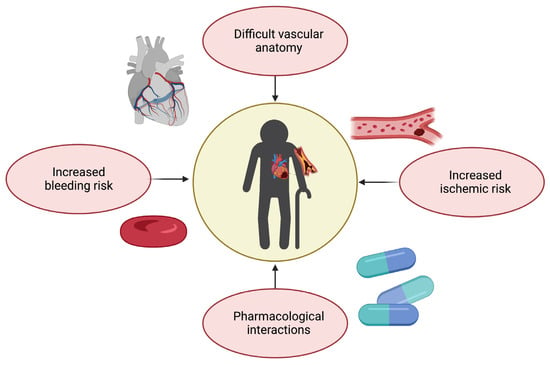

As previously discussed, the management of CAD in older adults requires a multidimensional clinical approach that goes beyond pre-defined therapeutic and nosographic algorithms (Figure 2). For instance, older adults are at high risk of both ischemic and bleeding events [38]. Multivessel disease is also frequent in old age [39]. Furthermore, advanced age is associated with adverse outcomes across the whole spectrum of ACSs, partly because of their frequent atypical presentation, which may delay their recognition and treatment [39].

Figure 2. Challenges in therapeutic management of coronary artery disease in older adults (created with Biorender.com, accessed on 30 June 2023).

Guidelines recommend the use of predictive tools such as the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI), Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) or GRACE 2.0 for risk assessment and management [8]. The TIMI score was designed to assess the risk of unfavorable outcomes in patients with ACS; however, its reliability in geriatric populations has been somewhat restricted [40]. The GRACE score has been validated in older adults; nevertheless, its accuracy in this subgroup might be reduced due to competing factors [41]. Interestingly, a study on 198 patients with type 1 myocardial infarction conducted by Anand et al. found that while the GRACE score alone overestimated mortality risk, a simple frailty screening tool such as the CFS was an independent predictor of mortality and significantly enhanced the GRACE 12-month mortality estimate [42]. GRACE 2.0 demonstrated better discrimination than the prior version and functioned equally well in acute and long-term circumstances [43]. According to Hung et al., GRACE 2.0 demonstrated high accuracy for prognostic stratification of patients with type 1 myocardial infarction and intermediate accuracy for those with type 2 myocardial infarction, who are often older and have more comorbidities [44].

Despite the underrepresentation of older patients in landmark clinical trials on ACS and the consequent lack of specific pharmacological and invasive treatment recommendations, the application of existing guidelines reduces mortality after hospital admission in this specific patient subgroup [45]. This may be due to an increasing application of invasive approaches to ACS in aged individuals, which showed a better benefit–risk ratio compared with conservative treatments in the setting of both ST elevation (STEMI)- and NSTEMI-ACS [46,47]. Indeed, current European guidelines recommend applying the same invasive approaches in older adults as in younger patients. In the setting of STEMI-ACS, European guidelines recommend coronary angiography with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) in patients of all ages within two hours of symptom onset. Within this timeframe, a pPCI strategy is recommended over fibrinolysis—otherwise, patients may receive fibrinolysis—and those ineligible for any reperfusion strategy should be treated medically with dual antiplatelet therapy [8]. In an emergency setting, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is limited to patients with ongoing ischemia with unsuitable anatomy for a percutaneous approach [8]. In the case of NSTEMI-ACS, European guidelines recommend performing coronary angiography and subsequent revascularization, if indicated, in patients at intermediate or higher risk of adverse outcomes, regardless of age [8]. Surgery is considered a more suitable option in patients with diabetes mellitus or complex multivessel disease and may become the only approach in case of coronary anatomy not amenable to PCI, unsuccessful PCI, or when surgical treatment of mechanical complications or concomitant valve disease is mandatory [8,48,49]. However, although these indications may be valid in more stable and more robust patients, in the majority of cases, surgical treatment of ACS has a very high risk both in the short and the long term [50], especially in aged individuals [51]. For this reason, surgical treatment is now very uncommon in clinical practice, especially in older patients.

Sedation plays an important role in ensuring the comfort and safety of PCI patients. However, administering sedation to older persons necessitates careful evaluation of possible hazards due to increased sensitivity to sedatives as a result of multimorbidity, as well as age-related changes in metabolism and clearance, which may raise the risk of oversedation, adverse reactions and delirium. Delirium is significantly associated with in-hospital mortality and an increased risk of postprocedural complications [52]. A recent expert panel of the American College of Cardiologists advised against using sedatives with a prolonged half-life, such as diphenhydramine and long-acting benzodiazepines [53]. Studies identify dexmedetomidine as a potential alternative for older patients because it demonstrates non-inferiority for light-to-moderate sedation compared to midazolam and propofol and decreases the occurrence of delirium, despite the development of hypertension, bradycardia, and tachycardia [54]. Although sedation-free protocols could reduce days without mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients, it was associated with higher risk of delirium [55]. To date, however, sufficient evidence on the optimal sedation strategy for older patients is lacking [56]. Dosing the serum [57] or cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers [58] may provide a new tool to guide decision-making for preventing delirium in the cardiac intensive care unit in the near future, although it has not yet proven to be sufficiently specific for this goal. For now, in older individuals, the appropriate sedation technique to ensure the greatest balance between patient comfort and hemodynamics may differ from patient to patient, depending on comorbidities, frailty, and general health state.

3. Medical Treatment

The optimization and dosage of all drugs is of utmost importance in older frail patients, with particular attention to antithrombotic agents, owing to the risk of side effects and drug interaction [59]. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics—potentially due to changes in the distribution of fat mass and lean mass, multimorbidity, and polypharmacy—are associated with an increased risk of drug toxicity and side effects in older patients [60]. Sarcopenia, for instance, may cause underestimation of glomerular filtration rate calculated using serum creatinine, leading to inappropriate direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) dosing and increased risk of bleeding [61]. Based on these observations, while aspirin remains the cornerstone for secondary CVD prevention [62], American guidelines do not endorse its use on a routine basis for primary prevention among adults over 70 years [63]. In particular, when prescribing dual antiplatelet treatment after ACS or PCI, it is pivotal to tailor its duration in order to maximize ischemic protection while limiting bleeding risk, even though this may be challenging due to an overlap between ischemic and bleeding risk in frail patients (Figure 2) [60]. However, in both the PRECISE-DAPT and the DAPT scores, as well as according to the Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk (ARC-HBR) consensus, age is an important parameter that tips the scale towards short dual antiplatelet treatment regimens [44,64,65]. Among P2Y12 receptor inhibitors, prasugrel is generally not recommended in patients over 75 since the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial reported excess bleeding risk, resulting in a neutral net clinical benefit in older patients [66]. Conversely, the use of ticagrelor is not restricted to aged patients after ACS, based on the results of the PLATO trial [67]. Similarly, no restrictions based on age for long-term ticagrelor use on top of aspirin are recommended in patients with previous spontaneous myocardial infarction deemed to be at high ischemic risk, based on the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial [68]. Eventually, the POPular AGE trial identified clopidogrel as a favorable alternative to ticagrelor in older patients with high bleeding risk, due to fewer bleeding events and non-inferiority in the combined endpoint of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and bleeding [69]. The trade-off between bleeding and ischemic risk becomes more challenging if we consider that 20–30% of older patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) need PCI and stenting for concomitant CAD. Indeed, a triple antithrombotic treatment (aspirin, P2Y12, and anticoagulant) has been associated with an almost four-fold higher risk of bleeding than oral anticoagulation (OAC) monotherapy [70,71]. Several studies have compared dual (i.e., single antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor plus OAC) with triple antithrombotic therapy with regard to bleeding drawbacks. Recently, an important meta-analysis of pooled data from three major randomized trials reported that dual antithrombotic treatments including DOACs and a P2Y12 inhibitor without aspirin were associated with significantly lower bleeding than vitamin K antagonist (VKA)-based triple antithrombotic therapy in AF patients undergoing PCI [55,72,73,74]. Hence, after an initial short period (up to one week in NSTE-ACS and stable CAD) of triple antithrombotic therapy with DOAC and dual antiplatelet treatment, in most old and frail patients with concomitant AF, dual antiplatelet therapy is recommended as the default strategy using a DOAC at the recommended dose for stroke prevention and a single oral antiplatelet agent (preferably clopidogrel) [8,75]. Nevertheless, it should be considered that frailty is an independent predictor of bleeding, and treatment should be carefully tailored to each patient’s risk–benefit balance [55,76]. The most recent evidence supports de-escalation strategies, which can be achieved in several ways [60]. First, one possible strategy could be shortening DAPT followed by aspirin, clopidogrel or ticagrelor monotherapy. Other options include guided strategies implementing platelet function testing or genetic testing [77] as well as unguided de-escalation [78,79].

Certain antidepressants interact with antithrombotic treatment, leading to an increased risk of bleeding by blocking platelet uptake of serotonin [80]. Therefore, the use of nonselective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors may be proposed, or a proton pump inhibitor may be prescribed in high-risk bleeding patients treated with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors.

Additional goals of medical therapy for CAD are to relieve symptoms, reduce cardiac workload, and prevent complications. For these purposes, recommended medications include nitrates, beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and statins [8]. However, their administration in older patients requires careful consideration due to several concerns.

Nitrates effectively relieve angina symptoms and improve coronary blood flow in ACS patients. They can help reduce the ischemic burden on the heart and provide symptomatic relief, thereby improving quality of life [81]. However, nitrates can cause a drop in blood pressure, leading to hypotension [82]. Older patients may be more susceptible to this side effect due to age-related changes in blood vessel elasticity and autonomic regulation, interactions with concomitant medications, as well as pre-existing conditions [83]. Therefore, a cautious monitoring of blood pressure is necessary when initiating nitrates in older patients, especially in those with pre-existing hypotension or orthostatic hypotension [84].

Together with nitrates, it is generally recommended to initiate beta blockers early in the management of ACS, ideally within the first 24 h, unless there are contraindications or specific patient factors that warrant delay [8]. Benefits of beta blockers include reducing myocardial oxygen demand, decreasing heart rate and blood pressure, preventing arrhythmias, and improving long-term outcomes [85,86]. However, they may be contraindicated or require cautious use in certain situations. For example, in patients with severe bronchospastic disease, nonselective beta blockers should be avoided or used with extreme caution due to the potential for exacerbating bronchospasm. The choice of specific beta blocker should be guided by the patient’s comorbidities and tolerability [87]. For example, if a patient has a history of heart failure, a beta blocker with additional alpha-blocking properties like carvedilol may be preferred [88].

ACE inhibitors and ARBs reduce mortality, prevent heart failure, and improve outcomes in ACS patients [89,90]. A decline in renal function in older patients may affect the metabolism and elimination of both ACE inhibitors and ARBs. Moreover, aged individuals may have an increased risk of developing hyperkalemia due to an age-related decline in renal function and comorbidities such as diabetes [91]. Dose adjustments and close monitoring of renal function and electrolyte levels are important, especially in patients with pre-existing renal impairment or those taking other medications that can increase potassium levels [92].

Statins are the mainstay of lipid-lowering therapy and have been extensively studied in ACS patients [93]. However, their use in older patients, especially over the age of 75, in primary prevention is a matter of ongoing debate. As highlighted by a systematic review and meta-analysis by Aeschbacher-Germann and colleagues [94], participants enrolled in most clinical trials on lipid-lowering therapies are not representative of the general population. Statin therapy should be guided by the patient’s risk profile, baseline low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level, tolerability, and predicted long-term benefits. Statins are metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzyme system (except for pravastatin, rosuvastatin, and pitavastatin) [95]. Competing factors such as interactions with medications that inhibit or induce the CYP450 system or reduced renal function, may increase circulating levels or decrease the effectiveness of statins [96,97,98,99,100]. Although the efficacy of statins may be questionable for primary prevention in adults older than 75 [101,102], their use at an appropriate (not suboptimal) dosage is effective in secondary prevention, and that is clearly presented in the available guidelines [103,104,105]. However, a recent meta-analysis of 10 observational studies with 815,667 primary prevention patients showed that statin therapy was associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality (hazard radio (HR) 0.86, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.79–0.93), CVD death (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.78–0.81), and stroke (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.76–0.94) and non-significantly associated with risk of myocardial infarction (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.53–1.02). The beneficial association of statins with the risk of all-cause mortality remained significant even at older ages (>75 years; HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.81–0.96) and in both men (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.74–0.76) and women (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.72–0.99) [106]. The STOPPFrail (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Frail adults with Limited Life Expectancy) consensus highlights that lipid-lowering therapies need a long time to provide benefits. For this reason, potential risks may outweigh benefits if administrated for a short period in older patients with limited life expectancy [107]. Further trials using composite endpoints may help better understand benefits of statins in older populations, while bempedoic acid could be a therapeutic option to overcome safety issues related to statin intolerance [108]. It is worth remembering that older age, per se, is a risk factor for statin intolerance (by even 31–33%) [109]. For this reason, a stepwise lipid lowering approach is indicated, starting with moderate-intensity statin therapy, or, in case of any adverse events, considering lipid-lowering combination therapy with an ezetimibe, bempedoic acid and PCSK9 targeted therapy approach, for which there is strong evidence of the safety and efficacy, including in aged populations [110].

In conclusion, when considering medical therapy in older adults with CAD, several important factors should be taken into account. These include the patient’s overall health status, comorbidities, functional limitations, and goals of care. Older adults may have age-related changes in drug metabolism, increased susceptibility to medication side effects, and a higher burden of polypharmacy. Therefore, a personalized approach to medical therapy is crucial, involving careful selection and titration of medications, regular monitoring for adverse effects, and frequent follow-up visits. To mitigate the risk of drug interactions in older patients with CAD, comprehensive medication reviews, including an assessment of the patient’s complete medication list, should be conducted regularly. A close monitoring for potential interactions, regular communication among healthcare providers, and patient education about their medications are essential to optimize treatment outcomes while minimizing the risks associated with drug interactions [111]. Collaboration between healthcare professionals, including cardiologists, geriatricians, and primary care physicians, is essential to ensure the optimal management of CAD in older adults, promoting both cardiovascular health and overall wellbeing [111].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm12165233

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!