Both biomedical applications and safety assessments of manufactured nanomaterials require a thorough understanding of the interaction between nanomaterials and cells, including how nanomaterials enter cells, transport within cells, and leave cells. Compared to the extensively studied uptake and trafficking of nanoparticles (NPs) in cells, less attention has been paid to the exocytosis of NPs. Yet exocytosis is an indispensable process of regulating the content of NPs in cells, which in turn influences, even decides, the toxicity of NPs to cells. A comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms and influencing factors of the exocytosis of NPs is not only essential for the safety assessment of NPs but also helpful for guiding the design of safe and highly effective NP-based materials for various purposes.

- exocytosis

- nanomaterials

- lysosomal

- Golgi

1. Introduction

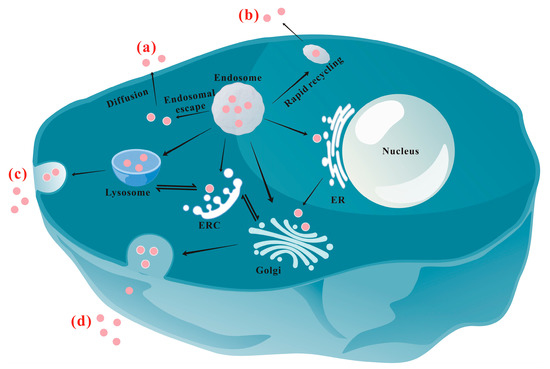

2. Exocytosis Mechanisms/Pathways of NPs

2.1. Lysosomal Pathway

| Chemical | Concentration | Pathway | Function | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor | NaN3/4 °C | -- | -- | Inhibiting cell membrane fluidity and energy-dependent transport | [71] |

| Bafilomycin A1 | 0.1~0.5 μM | Lysosomal | Inhibitor of endosomal acidification and lysosomal maturation | [50][68] | |

| Chloroquine | 100 μM | Lysosomal | pH buffering and inhibiting lysosomal enzymes | [72] | |

| LY294002 | 250 nM~1 mM | Lysosomal | Inhibiting PI3 kinase and lysosomal exocytosis | [10][69] | |

| Vacuolin-1 | 5 μM | Lysosomal | Inhibiting Ca2+-dependent lysosomal exocytosis | [69] | |

| Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) |

1~10 mM | Lysosomal | Cholesterol depletion | [60][73] | |

| Wortmannin | 10~33 µM | Lysosomal | Preventing the transport of endosomes to lysosomes | [17][74] | |

| U1866A | 2.5 µM | Lysosomal | Altering cholesterol accumulation and affecting different intracellular trafficking pathways | [10] | |

| Monensin | 14~50 μM | Golgi | Blocking transportation from the Golgi apparatus to the cell membrane | [68][75] | |

| Exo1 (2-(4-fluorobenzoylamino)-benzoic acid methyl ester) | 10~100 µM | Golgi | Inducing collapse of the Golgi apparatus | [10][37] | |

| Brefeldin A | 35~90 μM | ER/Golgi | Inhibiting transport from the ER to the Golgi apparatus | [59][68] | |

| Nocodazole | 15~33 μM | microtubule-associated transport | Inhibiting microtubule formation | [69][73] | |

| Cytochalasin D | 5 µM | -- | Disruption of actin polymerization | [69] | |

| Verapamil | 10 µM~2 mM | -- | P-glycoprotein inhibitor | [68][76] | |

| Fumitremorgin C | 5 µM | -- | MDR-associated protein inhibitor | [68] | |

| Accelerator | Ionomycin | 10 μM | Lysosomal | Accelerating exocytosis by transporting Ca2+ into the cells | [77] |

| A23817 | -- | Lysosomal | Promoting Ca2+ influx and accelerating lysosomal associated efflux | [78] | |

2.2. ER/Golgi Pathway

2.3. The Auxiliary Effect of the Microtubule

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nano13152215

References

- Zhu, W.; Wei, Z.; Han, C.; Weng, X. Nanomaterials as promising theranostic tools in nanomedicine and their applications in clinical disease diagnosis and treatment. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3346.

- Xuan, Y.; Gao, Y.T.; Guan, M.; Zhang, S.B. Application of “smart” multifunctional nanoprobes in tumor diagnosis and treatment. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 3601–3613.

- Dahiya, U.R.; Ganguli, M. Exocytosis—A putative road-block in nanoparticle and nanocomplex mediated gene delivery. J. Control. Release 2019, 303, 67–76.

- Manzanares, D.; Ceña, V. Endocytosis: The nanoparticle and submicron nanocompounds gateway into the cell. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 371.

- de Almeida, M.S.; Susnik, E.; Drasler, B.; Taladriz-Blanco, P.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. Understanding nanoparticle endocytosis to improve targeting strategies in nanomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 5397–5434.

- Sakhtianchi, R.; Minchin, R.F.; Lee, K.B.; Alkilany, A.M.; Serpooshan, V.; Mahmoudi, M. Exocytosis of nanoparticles from cells: Role in cellular retention and toxicity. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 201, 18–29.

- Reinholz, J.; Diesler, C.; Schöttler, S.; Kokkinopoulou, M.; Ritz, S.; Landfester, K.; Mailander, V. Protein machineries defining pathways of nanocarrier exocytosis and transcytosis. Acta Biomater. 2018, 71, 432–443.

- Serda, R.E.; Mack, A.; van de Ven, A.L.; Ferrati, S.; Dunner, K.; Godin, B.; Chiappini, C.; Landry, M.; Brousseau, L.; Liu, X.W.; et al. Logic-embedded vectors for intracellular partitioning, endosomal escape, and exocytosis of nanoparticles. Small 2010, 6, 2691–2700.

- Chu, Z.Q.; Huang, Y.J.; Tao, Q.; Li, Q. Cellular uptake, evolution, and excretion of silica nanoparticles in human cells. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 3291–3299.

- Yanes, R.E.; Tarn, D.; Hwang, A.A.; Ferris, D.P.; Sherman, S.P.; Thomas, C.R.; Lu, J.; Pyle, A.D.; Zink, J.I.; Tamanoi, F. Involvement of lysosomal exocytosis in the excretion of mesoporous silica nanoparticles and enhancement of drug delivery effect by exocytosis inhibition. Small 2013, 9, 697–704.

- Bartczak, D.; Nitti, S.; Millar, T.M.; Kanaras, A.G. Exocytosis of peptide functionalized gold nanoparticles in endothelial cells. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 4470.

- Kim, C.S.; Le, N.D.B.; Xing, Y.Q.; Yan, B.; Tonga, G.Y.; Kim, C.; Vachet, R.W.; Rotello, V.M. The role of surface functionality in nanoparticle exocytosis. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 1200–1202.

- Jiang, X.; Rocker, C.; Hafner, M.; Brandholt, S.; Dorlich, R.M.; Nienhaus, G.U. Endo- and exocytosis of zwitterionic quantum dot nanoparticles by live HeLa cells. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 6787–6797.

- Ohta, S.; Inasawa, S.; Yamaguchi, Y. Real time observation and kinetic modeling of the cellular uptake and removal of silicon quantum dots. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 4639–4645.

- Peng, L.; He, M.; Chen, B.B.; Wu, Q.M.; Zhang, Z.L.; Pang, D.W.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, B. Cellular uptake, elimination and toxicity of CdSe/ZnS quantum dots in Hep-G2 cells. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 9545–9558.

- Dombu, C.Y.; Kroubi, M.; Zibouche, R.; Matran, R.; Betbeder, D. Characterization of endocytosis and exocytosis of cationic nanoparticles in airway epithelium cells. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 355102.

- He, B.; Jia, Z.R.; Du, W.W.; Yu, C.; Fan, Y.C.; Dai, W.B.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.Q.; Wang, J.C.; et al. The transport pathways of polymer nanoparticles in MDCK epithelial cells. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 4309–4326.

- Agarwal, R.; Singh, V.; Jurney, P.; Shi, L.; Sreenivasan, S.V.; Roy, K. Mammalian cells preferentially internalize hydrogel nanodiscs over nanorods and use shape-specific uptake mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17247–17252.

- Tree-Udom, T.; Seemork, J.; Shyou, K.; Hamada, T.; Sangphech, N.; Palaga, T.; Insin, N.; Pan-In, P.; Wanichwecharungruang, S. Shape effect on particle-lipid bilayer membrane association, cellular uptake, and cytotoxicity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 23993–24000.

- He, B.; Lin, P.; Jia, Z.R.; Du, W.W.; Qu, W.; Yuan, L.; Dai, W.B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.Q.; Wang, J.C.; et al. The transport mechanisms of polymer nanoparticles in Caco-2 epithelial cells. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 6082–6098.

- Chen, R.; Huang, G.; Ke, P.C. Calcium-enhanced exocytosis of gold nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 093706.

- Kim, C.; Tonga, G.Y.; Yan, B.; Kim, C.S.; Kim, S.T.; Park, M.H.; Zhu, Z.J.; Duncan, B.; Creran, B.; Rotello, V.M. Regulating exocytosis of nanoparticles via host-guest chemistry. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 2474–2479.

- Ashraf, S.; Said, A.H.; Hartmann, R.; Assmann, M.A.; Feliu, N.; Lenz, P.; Parak, W.J. Quantitative particle uptake by cells as analyzed by different methods. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5438–5453.

- Wilson, C.L.; Natarajan, V.; Hayward, S.L.; Khalimonchuk, O.; Kidambi, S. Mitochondrial dysfunction and loss of glutamate uptake in primary astrocytes exposed to titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 18477–18488.

- Manshian, B.B.; Martens, T.F.; Kantner, K.; Braeckmans, K.; De Smedt, S.C.; Demeester, J.; Jenkins, G.J.S.; Parak, W.J.; Pelaz, B.; Doak, S.H.; et al. The role of intracellular trafficking of CdSe/ZnS QDs on their consequent toxicity profile. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 15, 45.

- Liu, N.; Liang, Y.; Wei, T.T.; Zou, L.Y.; Bai, C.C.; Huang, X.Q.; Wu, T.S.; Xue, Y.Y.; Tang, M.; Zhang, T. Protein corona mitigated the cytotoxicity of CdTe QDs to macrophages by targeting mitochondria. NanoImpact 2022, 25, 100367.

- Xi, W.S.; Li, J.B.; Tang, X.R.; Tan, S.Y.; Cao, A.N.; Liu, Y.F.; Wang, H.F. Cytotoxicity and RNA-sequencing analysis of macrophages after exposure to vanadium dioxide nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Nano 2022, 9, 4524–4539.

- Wang, L.M.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Jiang, X.M.; Ji, Y.L.; Wu, X.C.; Xu, L.G.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, K.; Wei, T.T.; et al. Selective targeting of gold nanorods at the mitochondria of cancer cells: Implications for cancer therapy. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 772–780.

- Boakye-Yiadom, K.O.; Kesse, S.; Opoku-Damoah, Y.; Filli, M.S.; Aquib, M.; Joelle, M.M.B.; Farooq, M.A.; Mavlyanova, R.; Raza, F.; Bavi, R.; et al. Carbon dots: Applications in bioimaging and theranostics. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 564, 308–317.

- Dean, D.A.; Strong, D.D.; Zimmer, W.E. Nuclear entry of nonviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2005, 12, 881–890.

- Corvaglia, S.; Guarnieri, D.; Pompa, P.P. Boosting the therapeutic efficiency of nanovectors: Exocytosis engineering. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 3757–3765.

- Chen, L.Q.; Liu, C.D.; Xiang, Y.C.; Lyu, J.Y.; Zhou, Z.; Gong, T.; Gao, H.L.; Li, L.; Huang, Y. Exocytosis blockade of endoplasmic reticulum-targeted nanoparticle enhances immunotherapy. Nano Today 2022, 42, 101356.

- Feng, Q.S.; Xu, X.Y.; Wei, C.; Li, Y.Z.; Wang, M.; Lv, C.; Wu, J.J.; Dai, Y.L.; Han, Y.; Lesniak, M.S.; et al. The dynamic interactions between nanoparticles and macrophages impact their fate in brain tumors. Small 2021, 17, 2103600.

- Panyam, J.; Labhasetwar, V. Dynamics of endocytosis and exocytosis of poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 212–220.

- Oh, N.; Park, J.H. Endocytosis and exocytosis of nanoparticles in mammalian cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 51–63.

- Liu, Y.Y.; Chang, Q.; Sun, Z.X.; Liu, J.; Deng, X.Y.; Liu, Y.F.; Cao, A.N.; Wang, H.F. Fate of CdSe/ZnS quantum dots in cells: Endocytosis, translocation and exocytosis. Colloids Surf. B 2021, 208, 112140.

- Ding, L.; Zhu, Z.B.; Wang, Y.L.; Shi, B.Y.; Ling, X.; Chen, H.J.; Nan, W.H.; Barrett, A.; Guo, Z.L.; Tao, W.; et al. Intracellular fate of nanoparticles with polydopamine surface engineering and a novel strategy for exocytosis-inhibiting, lysosome impairment-based cancer therapy. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 6790–6801.

- Kong, N.; Ding, L.; Zeng, X.B.; Wang, J.Q.; Li, W.L.; Shi, S.J.; Gan, S.T.; Zhu, X.B.; Tao, W.; Ji, X.Y. Comprehensive insights into intracellular fate of WS2 nanosheets for enhanced photothermal therapeutic outcomes via exocytosis inhibition. Nanophotonics 2019, 8, 2331–2346.

- Yan, G.H.; Song, Z.M.; Liu, Y.Y.; Su, Q.Q.; Liang, W.X.; Cao, A.N.; Sun, Y.P.; Wang, H.F. Effects of carbon dots surface functionalities on cellular behaviors-Mechanistic exploration for opportunities in manipulating uptake and translocation. Colloids Surf. B 2019, 181, 48–57.

- Shang, L.; Nienhaus, K.; Nienhaus, G.U. Engineered nanoparticles interacting with cells size matters. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2014, 12, 5.

- Frohlich, E. Cellular elimination of nanoparticles. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 46, 90–94.

- Graczyk, A.; Rickman, C. Exocytosis through the lens. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 147.

- McMahon, H.T.; Boucrot, E. Membrane curvature at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 1065–1070.

- Varela, J.A.; Bexiga, M.G.; Aberg, C.; Simpson, J.C.; Dawson, K.A. Quantifying size-dependent interactions between fluorescently labeled polystyrene nanoparticles and mammalian cells. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2012, 10, 39.

- Chen, W.B.; D’Argenio, D.Z.; Sipos, A.; Kim, K.J.; Crandall, E.D. Biokinetic modeling of nanoparticle interactions with lung alveolar epithelial cells: Uptake, intracellular processing, and egress. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2021, 320, R36–R43.

- Yang, M.; Wang, W.X. Recognition and movement of polystyrene nanoplastics in fish cells. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 316, 120627.

- Malik, S.; Saltzman, W.M.; Bahal, R. Extracellular vesicles mediated exocytosis of antisense peptide nucleic acids. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 25, 302–315.

- Qi, Z.T.; Jiang, C.P.; Gao, H.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Zhang, W.L.; Liu, J.P. Endocytic recycling as cellular trafficking fate of simvastatin-loaded discoidal reconstituted high-density lipoprotein to coordinate cholesterol efflux and drug influx. Nanomed-Nanotechnol. Bio. Med. 2021, 32, 102323.

- Han, S.W.; Ryu, K.Y. Increased clearance of non-biodegradable polystyrene nanoplastics by exocytosis through inhibition of retrograde intracellular transport. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 439, 129576.

- Sipos, A.; Kim, K.J.; Chow, R.H.; Flodby, P.; Borok, Z.; Crandall, E.D. Alveolar epithelial cell processing of nanoparticles activates autophagy and lysosomal exocytosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2018, 315, L286–L300.

- Raj, N.; Greune, L.; Kahms, M.; Mildner, K.; Franzkoch, R.; Psathaki, O.E.; Zobel, T.; Zeuschner, D.; Klingauf, J.; Gerke, V. Early Endosomes act as local exocytosis hubs to repair endothelial membrane damage. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2300244.

- Stenmark, H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 513–525.

- Yousuf, M.A.; Zhou, X.H.; Mukherjee, S.; Chintakuntlawar, A.V.; Lee, J.Y.; Ramke, M.; Chodosh, J.; Rajaiya, J. Caveolin-1 associated adenovirus entry into human corneal cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77462.

- Bhuin, T.; Roy, J.K. Rab proteins: The key regulators of intracellular vesicle transport. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 328, 1–19.

- Rajendran, L.; Udayar, V.; Goodger, Z.V. Lipid-anchored drugs for delivery into subcellular compartments. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 33, 215–222.

- Ding, H.; Yang, D.Y.; Zhao, C.; Song, Z.K.; Liu, P.C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.J.; Shen, J.C. Protein-gold hybrid nanocubes for cell imaging and drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 4713–4719.

- Al-Hajaj, N.A.; Moquin, A.; Neibert, K.D.; Soliman, G.M.; Winnik, F.M.; Maysinger, D. Short ligands affect modes of QD uptake and elimination in human cells. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 4909–4918.

- Cui, Y.N.; Song, X.N.; Li, S.X.; He, B.; Yuan, L.; Dai, W.B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.Q.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Q. The impact of receptor recycling on the exocytosis of αvβ3 integrin targeted gold nanoparticles. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 38618–38630.

- Bae, Y.M.; Park, Y.I.; Nam, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, K.; Kim, H.M.; Yoo, B.; Choi, J.S.; Lee, K.T.; Hyeon, T.; et al. Endocytosis, intracellular transport, and exocytosis of lanthanide-doped up-converting nanoparticles in single living cells. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 9080–9086.

- Strobel, C.; Oehring, H.; Herrmann, R.; Forster, M.; Reller, A.; Hilger, I. Fate of cerium dioxide nanoparticles in endothelial cells: Exocytosis. J. Nanopart. Res. 2015, 17, 206.

- Xing, L.Y.; Zheng, Y.X.; Yu, Y.L.; Wu, R.N.; Liu, X.; Zhou, R.; Huang, Y. Complying with the physiological functions of Golgi apparatus for secretory exocytosis facilitated oral absorption of protein drugs. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 1707–1718.

- Zhang, W.Q.; Ji, Y.L.; Wu, X.C.; Xu, H.Y. Trafficking of gold nanorods in breast cancer cells: Uptake, lysosome maturation, and elimination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 9856–9865.

- Slowing, I.I.; Vivero-Escoto, J.L.; Zhao, Y.; Kandel, K.; Peeraphatdit, C.; Trewyn, B.G.; Lin, V.S.Y. Exocytosis of mesoporous silica nanoparticles from mammalian cells: From asymmetric cell-to-cell transfer to protein harvesting. Small 2011, 7, 1526–1532.

- Zhang, J.X.; Zhang, X.D.; Liu, G.; Chang, D.F.; Liang, X.; Zhu, X.B.; Tao, W.; Mei, L. Intracellular trafficking network of protein nanocapsules: Endocytosis, exocytosis and autophagy. Theranostics 2016, 6, 2099–2113.

- Bao, F.X.; Zhou, L.Y.; Zhou, R.; Huang, Q.Y.; Chen, J.G.; Zeng, S.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Qian, S.F.; Wang, M.F.; et al. Mitolysosome exocytosis, a mitophagy-independent mitochondrial quality control in flunarizine-induced parkinsonism-like symptoms. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabk2376.

- Sha, L.P.; Zhao, Q.F.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Wang, X.D.; Guan, X.Y.; Wang, S.L. “Gate” engineered mesoporous silica nanoparticles for a double inhibition of drug efflux and particle exocytosis to enhance antitumor activity. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 535, 380–391.

- Liu, L.; Xu, K.X.; Zhang, B.W.; Ye, Y.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, W. Cellular internalization and release of polystyrene microplastics and nanoplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 779, 146523.

- Zhang, J.; Li, M.J.; Wang, M.Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z.X.; Li, Y.; Ding, B.Y.; Gao, J.Q. Effects of the surface charge of polyamidoamine dendrimers on cellular exocytosis and the exocytosis mechanism in multidrug-resistant breast cancer cells. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 135.

- Liu, Y.Y.; Sun, Z.X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Liu, Y.F.; Cao, A.E.; Sun, Y.P.; Wang, H.F. On the cellular uptake and exocytosis of carbon dots significant cell-type dependence and effects of cell division. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 4378–4389.

- Luzio, J.P.; Gray, S.R.; Bright, N.A. Endosome-lysosome fusion. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010, 38, 1413–1416.

- Fiorentino, I.; Gualtieri, R.; Barbato, V.; Mollo, V.; Braun, S.; Angrisani, A.; Turano, M.; Furia, M.; Netti, P.A.; Guarnieri, D. Energy independent uptake and release of polystyrene nanoparticles in primary mammalian cell cultures. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 330, 240–247.

- Zheng, Y.X.; Xing, L.Y.; Chen, L.Q.; Zhou, R.; Wu, J.W.; Zhu, X.; Li, L.; Xiang, Y.C.; Wu, R.N.; Zhang, L.; et al. Tailored elasticity combined with biomimetic surface promotes nanoparticle transcytosis to overcome mucosal epithelial barrier. Biomaterials 2020, 262, 120323.

- Xu, Y.N.; Xu, J.; Shan, W.; Liu, M.; Cui, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, C.; Huang, Y. The transport mechanism of integrin alpha(v)beta(3) receptor targeting nanoparticles in Caco-2 cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 500, 42–53.

- Jiang, L.Q.; Wang, T.Y.; Webster, T.J.; Duan, H.J.; Qiu, J.Y.; Zhao, Z.M.; Yin, X.X.; Zheng, C.L. Intracellular disposition of chitosan nanoparticles in macrophages: Intracellular uptake, exocytosis, and intercellular transport. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 12, 6383–6398.

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, J.; Lu, W.Y.; Zhan, C.Y. Unraveling GLUT-mediated transcytosis pathway of glycosylated nanodisks. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 16, 120–128.

- Wu, S.J.; Siu, K.C.; Wu, J.Y. Involvement of anion channels in mediating elicitor-induced ATP efflux in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 168, 128–132.

- Escrevente, C.; Bento-Lopes, L.; Ramalho, J.S.; Barral, D.C. Rab11 is required for lysosome exocytosis through the interaction with Rab3a, Sec15 and GRAB. J. Cell Sci. 2021, 134, jcs246694.

- Ekkapongpisit, M.; Giovia, A.; Nicotra, G.; Ozzano, M.; Caputo, G.; Isidoro, C. Labeling and exocytosis of secretory compartments in RBL mastocytes by polystyrene and mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 1829–1840.

- Ross, N.L.; Munsell, E.V.; Sabanayagam, C.; Sullivan, M.O. Histone-targeted polyplexes avoid endosomal escape and enter the nucleus during postmitotic redistribution of ER membranes. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2015, 4, e226.

- Xu, Y.N.; Zheng, Y.X.; Wu, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Z.R.; Huang, Y. Novel solid lipid nanoparticle with endosomal escape function for oral delivery of insulin. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 9315–9324.

- Lowe, S.; Peter, F.; Subramaniam, V.N.; Wong, S.H.; Hong, W.J. A SNARE involved in protein transport through the Golgi apparatus. Nature 1997, 389, 881–884.

- Jahn, R.; Scheller, R.H. SNAREs-engines for membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 631–643.

- Rohl, J.; West, Z.E.; Rudolph, M.; Zaharia, A.; Van Lonkhuyzen, D.; Hickey, D.K.; Semmler, A.B.T.; Murray, R.Z. Invasion by activated macrophages requires delivery of nascent membrane-type-1 matrix metalloproteinase through late endosomes/lysosomes to the cell surface. Traffic 2019, 20, 661–673.

- Nan, X.; Sims, P.A.; Chen, P.; Xie, X.S. Observation of individual microtubule motor steps in living cells with endocytosed quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 24220–24224.

- Schliwa, M.; Woehlke, G. Molecular motors. Nature 2003, 422, 759–765.

- Han, S.; da Costa Marques, R.; Simon, J.; Kaltbeitzel, A.; Koynov, K.; Landfester, K.; Mailander, V.; Lieberwirth, I. Endosomal sorting results in a selective separation of the protein corona from nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 295.

- Cao, Z.H.; Peng, F.; Hu, Z.L.; Chu, B.B.; Zhong, Y.L.; Su, Y.Y.; He, S.D.; He, Y. In vitro cellular behaviors and toxicity assays of small-sized fluorescent silicon nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 7602–7611.

- Gupta, K.; Brown, K.A.; Hsieh, M.L.; Hoover, B.M.; Wang, J.X.; Khoury, M.K.; Pilli, V.S.S.; Beyer, R.S.H.; Voruganti, N.R.; Chaudhary, S. Necroptosis is associated with Rab27-independent expulsion of extracellular vesicles containing RIPK3 and MLKL. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12261.