Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Social prescribing initiatives are tailored coaching programs created to assist participants in improving their personal circumstances and might constitute a creative way to enhance public and preventive health as researchers work toward providing universal financially sustainable healthcare.

- social prescribing

- Romanian

1. Introduction

Social prescribing initiatives are personalized coaching initiatives designed to help participants better cope with their personal situations and, as a result, lower their need for medical and social services [1]. Healthcare professionals can facilitate patients’ access to a variety of community-based non-clinical services to enhance their health and well-being through social prescribing [2][3]. The precise “social prescriptions” are unique to each community and care environment, but they often include programs promoting physical exercise and artistic expression as well as mental health support, social inclusion, financial guidance, and housing advice [4][5]. Through social prescribing, people can access non-medical assistance for coping with these problems and other unmet requirements [5].

The social prescribing movement has rapidly expanded in the past few years, leading the health and non-profit sectors from many countries to adopt a variety of concepts, procedures, and methodologies [6][7][8]. Even though social prescribing can take various paths, the most widely used model benefits highly from the involvement of link workers, who are specialized in identifying the individual needs of the patient. Ideally, the link workers follow the patient’s progress and build up a team with the healthcare provider in the form of the general practitioner or healthcare facility [2]. According to Husk, “social prescribing” refers to the patient’s journey from primary care to whatever activity is conducted [9]. Based on that, researchers have provided a simplified representation of the possible pathways that might be involved in it.

One of the most common activities recommended in social prescribing is group exercise or physical activity, with beneficial results in patients with chronic pain [10], disability [11], dementia [12], and mental health problems [13][14]. People with a variety of health and social issues can benefit from gardens and gardening in terms of their health and well-being. Globally, the advantages of gardening could be used as a “social prescription” for individuals with chronic illnesses [15] as well as ease some health challenges that humanity is currently confronting [16].

Additionally, other social prescribing interventions have been proven to have a positive influence on health outcomes. For example, music therapy has shown significant positive effects on the emotional well-being, social engagement, and overall psycho-social well-being of individuals with dementia, particularly those with moderate dementia. Studies have highlighted the benefits of music intervention in alleviating depression and anxiety in this population. Through singing, music therapy interventions have demonstrated improvements in feelings, emotions, and social interaction. Specifically, weekly short interventions lasting more than 45 min were found to be effective in regulating emotions [17].

However, the implementation of music therapy as a social prescription faces challenges such as the formalization of the social prescribing process, securing buy-ins from healthcare professionals, sustainable funding, and institutional knowledge retention [18].

In the face of the increasing the burden of chronic diseases, low levels of prevention, and rising healthcare costs, the identification of innovative solutions, including those beyond the healthcare system, is imperative. According to the Eurostat database, the per capita health cost in Romania was the second lowest in the European Union [19] in 2015. Further investigations have revealed that Romania had an average of USD 830 in health spending per person in 2019, with a projection for this figure to increase up to USD 1040 by 2026 [20]. Since the majority of the costs comes from the public health system, vulnerable groups (the unemployed Roma population and pensionaries) and overall rural populations with lower accessibility to medical services face unmet medical needs [21], making social prescribing initiatives a promising approach to building a sustainable healthcare system, emphasizing prevention, and leveraging other complementary resources and interventions.

Given the lack of research at the national level and the emerging body of evidence brought by international research on the benefits of social prescribing, especially on long-term sustainable healthcare, an analysis of the opportunities for social prescribing is necessary.

2. The Healthcare System—Structure and Potential Role in Social Prescribing

The healthcare system in Romania comprises various medical structures, public and private organizations, and resources aimed at preventing, maintaining, improving, and restoring the health of the population. The Ministry of Health and its specialized structures have a responsibility to coordinate the public healthcare system at the national and territorial levels.

Primary healthcare is the initial point of contact for individuals, providing comprehensive care encompassing the physical, psychological, and social aspects of health, and it has a privileged position to benefit from social prescribing. It focuses on prevention, health promotion, acute and chronic care, home care, and community-based medical services.

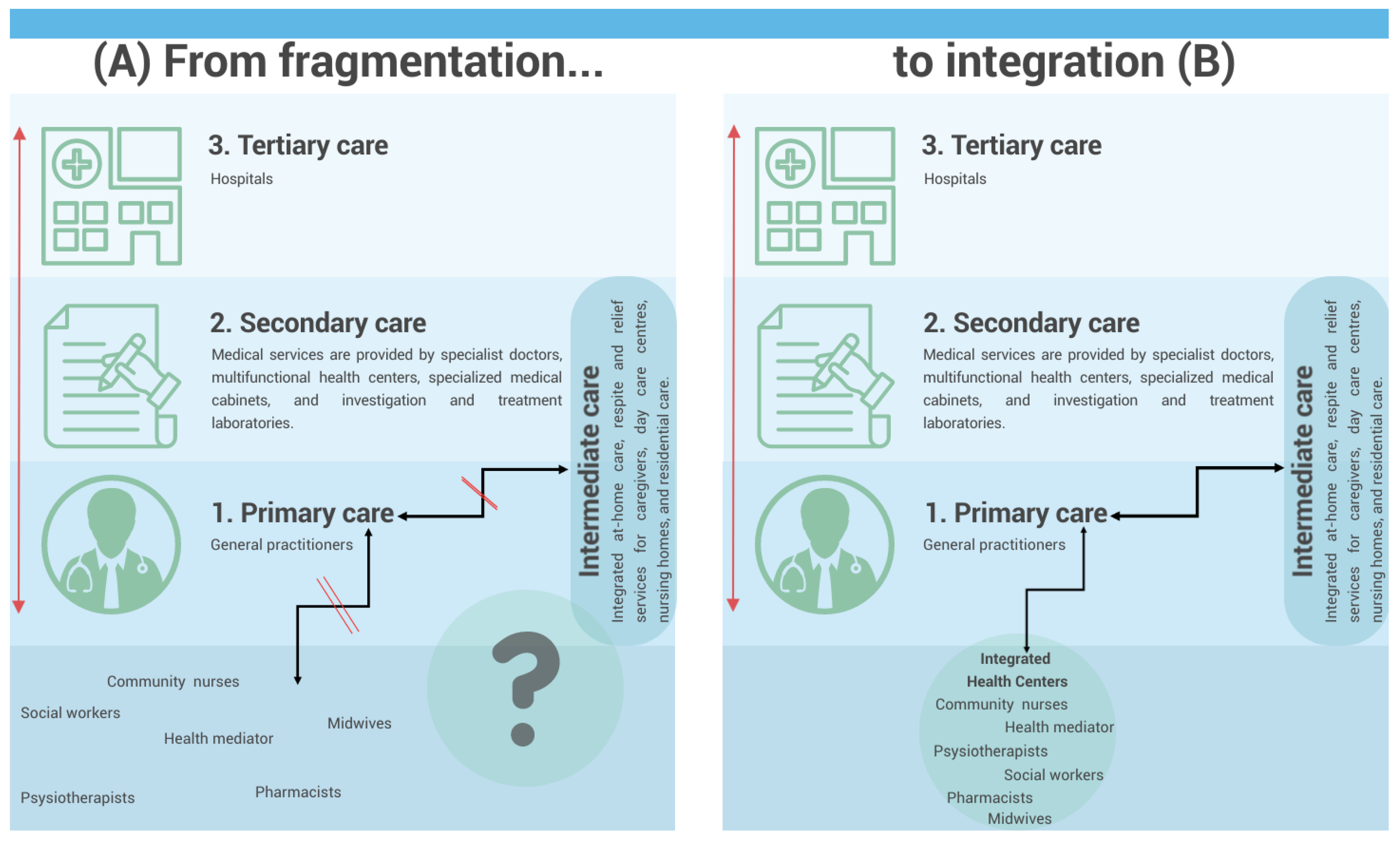

In Romania, primary healthcare is assimilated to general practitioners (GPs), named family doctors. Community healthcare workers (Figure 1) are a distinct part of the system, but they should cooperate with family doctors, especially in rural areas. They work independently, coordinated by the county health authorities, but no integration with primary care was established until recently when the Ministry of Health launched a call for integrated community centers aimed at collaboration between primary care physicians; public social assistance services; and other healthcare, social, and educational service providers, including non-governmental organizations specialized in these fields [22]. Figure 1A illustrated the fragmentation of care, a schematic representation of the Romanian healthcare system, emphasizing an important aspect: a significant part of the system, including community healthcare workers, midwives, healthcare mediators, pharmacists, psychotherapists, and social workers, currently lacks a clear connection with primary care and family doctors (general practitioners, GPs). This fragmentation hinders the effective implementation of social prescribing initiatives.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the Romanian healthcare system and its potential pathways for social prescription.

The perspective of future Integrated community centers is to play a pivotal role in addressing this issue. These centers can serve as a means of integrating all these healthcare actors, who are currently not adequately connected to primary care. By establishing direct links with family doctors, these centers can bridge the gap and create a collaborative environment that fosters effective social prescribing practices (Figure 1B).

By operating within communities, community health centers are well-positioned to understand the unique needs and challenges faced by vulnerable groups. Through collaboration with various stakeholders, including healthcare providers, social services, and educational institutions, these units can identify appropriate social prescribing initiatives that address the specific needs of individuals. By prescribing social interventions and support services alongside medical treatment, integrated community health centers can contribute to holistic and comprehensive care for vulnerable populations, promoting better health outcomes and overall well-being [23].

Another level of integration with primary care could be intermediate care units. Intermediate care units aim to provide integrated at-home care, respite and relief services for caregivers, day care centers, nursing homes, and residential care [24]. For patients with special needs, intermediate care units bridge the gap between primary and secondary care (Figure 1).

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su151511652

References

- Vidovic, D.; Reinhardt, G.Y.; Hammerton, C. Can Social Prescribing Foster Individual and Community Well-Being? A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5276.

- WHO. A Toolkit on How to Implement Social Prescribing; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Kurpas, D.; Mendive, J.M.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Petrazzuoli, F.; Morad, M.; Kloppe, T.; Herrman, W.; Mrduljaš-Đujić, N.; Kenkre, J. European Perspective on How Social Prescribing Can Facilitate Health and Social Integrated Care in the Community. Int. J. Integr. Care 2023, 23, 13.

- Coulter, A.; Entwistle, V.A.; Eccles, A.; Ryan, S.; Shepperd, S.; Perera, R. Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, Cd010523.

- A Social Revolution of Wellbeing-Strategic Plan 2022–2023. Available online: https://socialprescribingacademy.org.uk/media/mzrh4imh/nasp_strategic-plan_web.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Howarth, M.; Griffiths, A.; da Silva, A.; Green, R. Social prescribing: A ‘natural’ community-based solution. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2020, 25, 294–298.

- Baska, A.; Kurpas, D.; Kenkre, J.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Petrazzuoli, F.; Dolan, M.; Śliż, D.; Robins, J. Social Prescribing and Lifestyle Medicine—A Remedy to Chronic Health Problems? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 96.

- NHS.uk. Personalised Care—Social Prescribing. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/social-prescribing/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Husk, K.; Blockley, K.; Lovell, R.; Bethel, A.; Lang, I.; Byng, R.; Garside, R. What approaches to social prescribing work, for whom, and in what circumstances? A realist review. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 309–324.

- Geneen, L.J.; Moore, R.A.; Clarke, C.; Martin, D.; Colvin, L.A.; Smith, B.H. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: An overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 1, Cd011279.

- Shephard, R.J. Benefits of sport and physical activity for the disabled: Implications for the individual and for society. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1991, 23, 51–59.

- Nuzum, H.; Stickel, A.; Corona, M.; Zeller, M.; Melrose, R.J.; Wilkins, S.S. Potential Benefits of Physical Activity in MCI and Dementia. Behav. Neurol. 2020, 2020, 7807856.

- Peluso, M.A.; Guerra de Andrade, L.H. Physical activity and mental health: The association between exercise and mood. Clinics 2005, 60, 61–70.

- Petrazzuoli, F.; Vinker, S.; Palmqvist, S.; Midlöv, P.; Lepeleire, J.; Pirani, A.; Frese, T.; Buono, N.; Ahrensberg, J.; Asenova, R.; et al. Unburdening dementia—A basic social process grounded theory based on a primary care physician survey from 25 countries. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2020, 38, 253–264.

- Howarth, M.; Brettle, A.; Hardman, M.; Maden, M. What is the evidence for the impact of gardens and gardening on health and well-being: A scoping review and evidence-based logic model to guide healthcare strategy decision making on the use of gardening approaches as a social prescription. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036923.

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Yamaura, Y. Gardening is beneficial for health: A meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 5, 92–99.

- Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, W.; Wei, B.; He, R.; Xue, H.; Zhu, B.; Mao, Y. Does music intervention relieve depression or anxiety in people living with dementia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment. Health 2023, 1–12.

- Reschke-Hernández, A.E.; Gfeller, K.; Oleson, J.; Tranel, D. Music Therapy Increases Social and Emotional Well-Being in Persons with Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Crossover Trial Comparing Singing to Verbal Discussion. J. Music Ther. 2023, thad015.

- OECD; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Country Health Profile 2021; OECD: Paris, France; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: London, UK, 2021.

- Micah, A.E.; Bhangdia, K.; Cogswell, I.E.; Lasher, D.; Lidral-Porter, B.; Maddison, E.R.; Nguyen, T.N.N.; Patel, N.; Pedroza, P.; Solorio, J.; et al. Global investments in pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: Development assistance and domestic spending on health between 1990 and 2026. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e385–e413.

- Vladescu, C.; Scintee, S.G.; Olsavszky, V.; Hernandez-Quevedo, C.; Sagan, A. Romania: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2016, 18, 1–170.

- Planul National de Redresare si Rezilienta al Romaniei. Available online: https://mfe.gov.ro/pnrr/ (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- UNICEF. Centre Comunitare Integrate Aduc un Progres in Viata Copiilor Vulnerabili. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/romania/ro/pove%C8%99ti/centrele-comunitare-integrate-aduc-un-progres-%C3%AEn-via%C8%9Ba-copiilor-vulnerabili (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Dibao-Dina, C.; Oger, C.; Foley, T.; Torzsa, P.; Lazic, V.; Kreitmayer Peštiae, S.; Adler, L.; Kareli, A.; Mallen, C.; Heaster, C.; et al. Intermediate care in caring for dementia, the point of view of general practitioners: A key informant survey across Europe. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1016462.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!