The coronavirus disease pandemic, which profoundly reshaped the world in 2019 (COVID-19), has affected over 200 countries, caused over 500 million cumulative cases, and claimed the lives of over 6.4 million people worldwide as of August 2022. The causative agent is severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Depicting this virus’ life cycle and pathogenic mechanisms, as well as the cellular host factors and pathways involved during infection, has great relevance for the development of therapeutic strategies. Autophagy is a catabolic process that sequesters damaged cell organelles, proteins, and external invading microbes, and delivers them to the lysosomes for degradation. Autophagy would be involved in the entry, endo, and release, as well as the transcription and translation, of the viral particles in the host cell.

- COVID-19

- macroautophagy

- ATG proteins

- mitophagy

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Autophagy

3. Autophagy and the Viral Replication Cycle

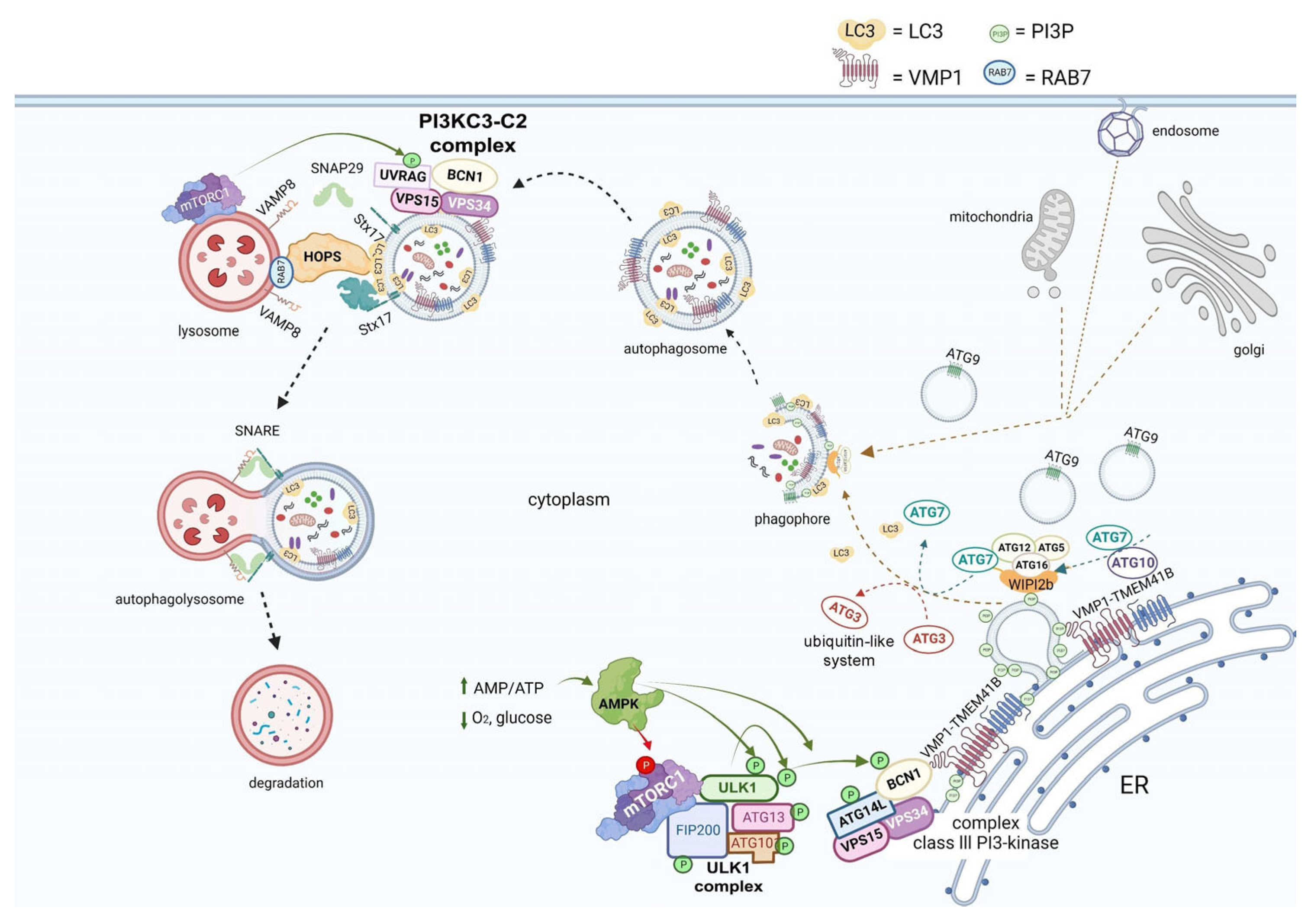

There is considerable evidence suggesting that autophagy could play a role in assisting with the viral replication cycle at different stages.

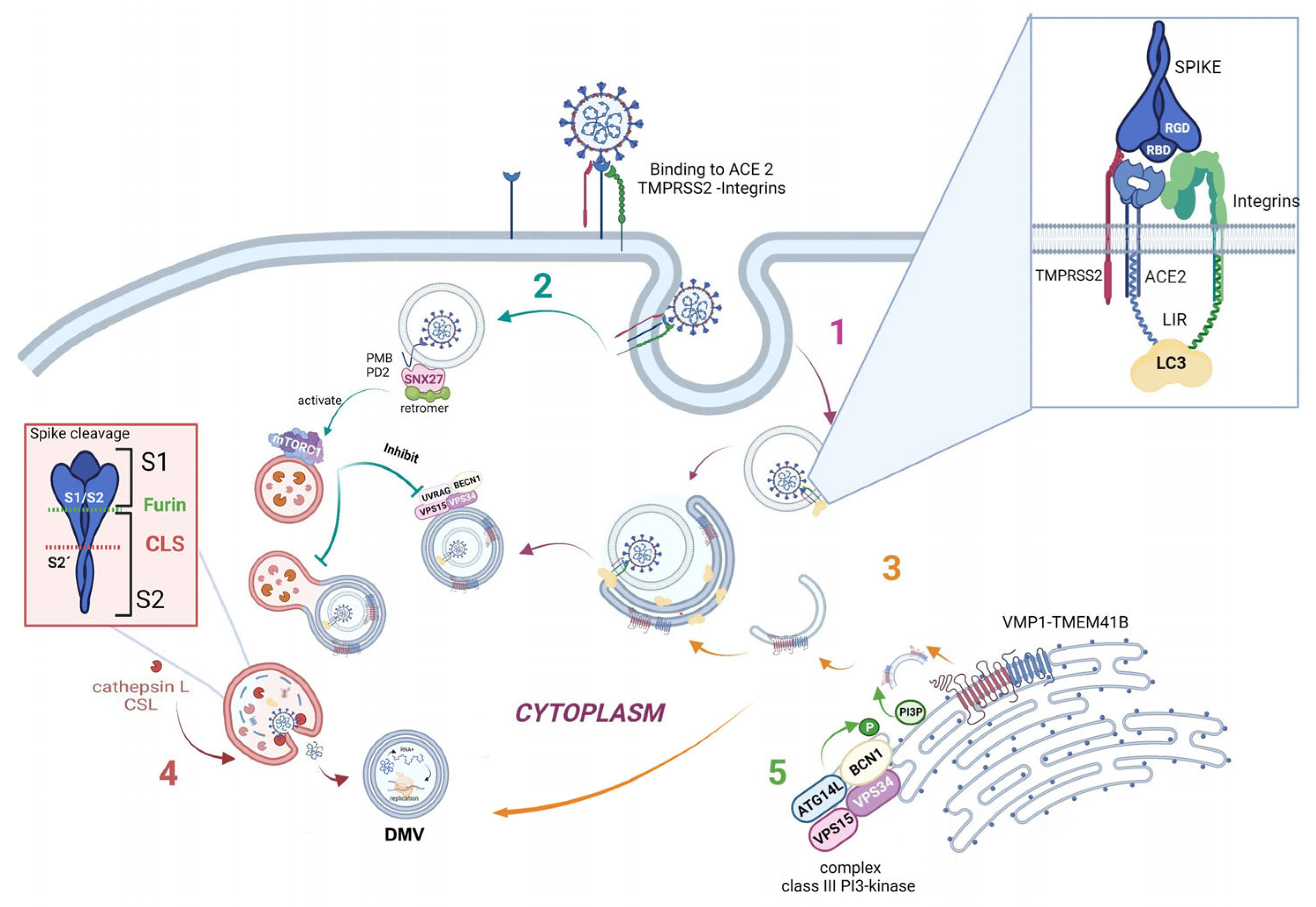

As is well known, the SARS-CoV-2 virus enters the host by binding its receptor-binding domain (RBD), located in the spike protein, to the ACE2 host cell receptor. Moreover, a bioinformatic analysis showed that two integrin-binding regions are present in the cytoplasmic C-terminal tail of the host ACE2 protein. Additionally, the viral S protein has an arginine–glycine–aspartic acid (RGD) motif-binding domain that links to integrins, suggesting that integrins could be used as co-receptors for viral entry [37].

Furthermore, one specific type of short linear motif (SLiM) has been found to be present in the tails of integrin β3 and ACE2. Thus, these structures from the autophagic machinery could be used to facilitate viral attachment, entry, and replication (as highlighted in the first step of Figure 3). Additionally, LC3-interacting region motifs (LIRs) have been identified in the tails of integrin β3 and ACE2. These LIRs are involved in the autophagic pathway through interaction with LC3, a marker of autophagosomes [38]. These LIR motifs also facilitate viral attachment, entry, and replication. Several viruses, including coronaviruses (CoVs), take advantage of cellular autophagy to facilitate their own replication.SARS-CoV-2 mediates its replication through a dependent or independent ATG5 pathway using specific double-membrane vesicles that can be considered similar to autophagosomes [39]

The virus enters the cell via the endosomal pathway. The spike protein is composed of two subunits: one binding subunit (S1) and one fusion subunit (S2). First, the S1 subunit binds to the host cell receptor ACE2. This union induces conformational changes in protein S. Second, the S2 subunit is activated. This activation occurs through two consecutive cleavage steps: a cleavage between the S1 and S2 domains of protein S by Furin is produced, and it then undergoes further cleavage at the S2’ site, which promotes the unmasking and activation of the fusion peptide [40]. To activate the spike protein’s fusion potential, a second cleavage performed by the host’s proteases is required. The cleavage can occur at different stages of the virus infection cycle by different host proteases, such as Furin (convertase), TMPRSS2 (cell surface protease), and Cathepsin L (lysosomal protease) [41][42]. Cathepsin L, which links the virus cycle to the autophagy process, acts at a low pH, degrades cargo, and maintains autolysosome homeostasis and autophagic flux. By cleaving the spike protein at S2’, it mediates virus membrane and autolysosome fusion, thus facilitating the release of viral RNA into the host cell. Smieszek et al., demonstrated that the inhibition of Cathepsin L could significantly reduce the entry of viruses into host cells [43]. It has also been shown that TMPRSS2, Furin, and Cathepsin L proteases have cumulative effects to activate virus entry and increase the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 [44][45] (Figure 3, pathway 4).

Once the virus has entered the cell, it uses the autophagy machinery for its own benefit through viral proteins, NSPs. Recently, as shown in Figure 3, pathway 3, transmembrane proteins related to autophagy, i.e., VMP1 and TEMEM41B, have been reported as critical host factors at the early stages of viral infection [45]. VMP1 and TMEM41B both contribute to different stages of DMV formation. Ji et al., have revealed that DMV biogenesis is impaired in VMP1 and TMEM41B knockout cells. Analysis using transmission electron microscopy revealed that the formation of DMVs was substantially inhibited in cells lacking these autophagy proteins. Hence, by inhibiting VMP1 and TMEM41B expression, the virus is unable to hide from the immune sensors in DMVs, thus reducing its protection from the immune system [46][47]. Shneider et al., showed that TMEM41B participates in the transport of lipids to the membrane and that, together with VMP1, they are involved in the remodeling of the ER to form double-membrane vesicles (DMV). Scudellari compared the double-membrane spheres to bubbles being blown by the endoplasmic reticulum [20]. These DMVs may act as replication organelles (RO), which might provide a safe place for viral RNA to be replicated and translated, protecting it from innate immune sensors in the cell, similar to other β coronaviruses. Therefore, these structures play a central role in infection, and, consequently, the loss of RO integrity due to the lack of VMP1 or TMEM41B could lead simultaneously to altered viral replication and enhanced antiviral signaling, as viral RNA is a very potent inducer of innate antiviral signaling [48].

SARS-CoV-2 mediates its replication through a dependent ATG5 pathway using specific DMVs that can be considered similar to autophagosomes. Mutations in the NSP6 protein with a positive influence on autophagosome production suggest a potential link with autophagy[49]. Thus, researchers hypothesize that some of these DMVs could be related to autophagy structures, and, more specifically, to autophagosomes. Researchers are certain that, in the near future, it will be found that well-described autophagy markers colocalize with these DMVs in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells.

Another connecting pathway between the viral replication cycle and autophagy is represented by SNX27, one of the sorting nexin (SNX) family members, which down-regulates autophagy by increasing the level of mTORC1 signaling [50]. Figure 3, pathway 2 shows how SNX27 regulates the traffic of endosomal receptors towards recycling endosomes. Kim et al., found that mTORC1 acts as a signal integrator at the lysosome and can act as an inhibitor of later stages of autophagy, suppressing phosphorylation on UVRAG, which is a component of VPS 34 complex II. In this way, it avoids autophagosome and endosome maturation [50]. These events are relevant for the viral cycle, given that the virus enters the cell via directly fusing to the membranes in the cell surface pathway or via the endocytic pathway through endosome/lysosome-mediated endocytosis. Interestingly, it has recently been found that the ACE2 receptor possesses a type I PDZ binding motif (PBM) and can therefore interact with a PDZ domain-containing protein such as SNX27. A recent study has shown SNX27 to be critical for ACE2 cell surface regulation, and SNX27 prevents ACE2-bonded viral particles from entering the lysosome, down-regulating the endocytic viral entry pathway and therefore serving as a viral trafficking regulator [51].

Regarding autophagy machinery, a class III PI3-kinase that produces PI3P has a role in cellular trafficking and in the nucleation step in both canonical and non-canonical autophagy. In fact, inhibition of VPS34 kinase activity by VPS34-IN1, a well-known inhibitor for this kinase, reduced PI3P production and suppressed SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication in ex vivo human lung tissues [52] (Figure 3, pathway 5).

The features mentioned above provide consistent evidence that the autophagy machinery is actively involved in the viral entry and replication process of SARS-CoV-2 infection and therefore could be used as potential therapeutic targets to battle infection and prevent viral entry and replication at different steps.4. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Its Effects on Autophagy

Although strong evidence points toward the SARS-CoV-2 virus having an inhibiting role in some stages of autophagy, paradoxically, it has been suggested that the virus enhances autophagy in other steps of this process. Li et al., explored the regulatory role of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in infected cells and attempted to elucidate the molecular mechanism of SARS-CoV-2-induced inflammation. They found that SARS-CoV-2 inhibits the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway by upregulating intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, and, in this way, promotes the autophagic response. Subsequently, SARS-CoV-2-induced autophagy triggers inflammatory responses and apoptosis in infected cells [53].

Recent studies suggest that SARS-CoV-2 inhibits autophagy at different stages, limiting the autophagic flux to suppress viral clearance by selective autophagy, known as virophagy, a process mediated by autophagy receptors that recognize and sequester viral components inside autophagosomes. To avoid virus inactivation, SARS-CoV-2 uses the autophagy machinery for its benefit [14]. Autophagy also regulates adaptive immunity through antigen presentation. Gassen and colleagues found that SARS-CoV-2 modulates cellular metabolism and reduces autophagy; therefore, the induction of autophagy limits SARS-CoV-2 propagation [16]. Autophagy machinery proteins and viral proteins interact, leading SARS-CoV-2 to successfully survive and complete the replication cycle in the infected host cells.

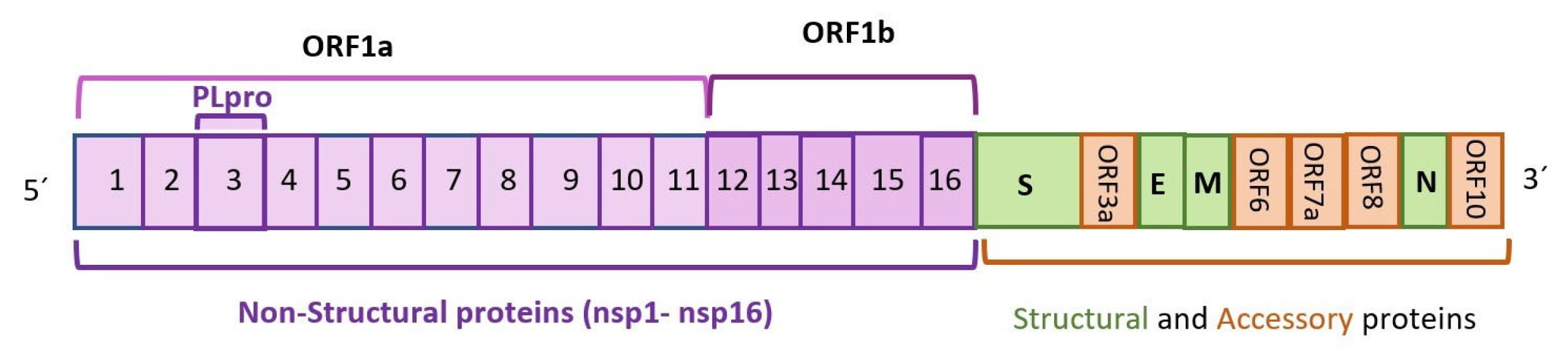

Regarding SARS-CoV proteins, Mohamud and colleagues have shown that NSP3 can cleave the serine/threonine unc-51-like kinase (ULK1) and prevent the formation of the autophagy initiation complex in the absence of nutrients. Another recent study showed that different viral proteins targeted and inhibited autophagy to avoid viral clearance and to block the antiviral functions of autophagy [54]. SARS-CoV-2 uses autophagy to its benefit, hijacking the autophagy mechanism in the host cell to improve viral replication and to avoid the immune response and extracellular release. Viral proteins ORF3a and ORF7a were shown to cause the accumulation of autophagosomes [55]. Specifically, ORF3a interacts with autophagy-related protein UVRAG, suppressing autophagosome maturation and therefore the autophagy flux.

In two other studies, it was demonstrated that ORF3a interacts with VPS39, colocalizing with lysosomes. In this way, it impairs the binding of HOPS with RAB7, avoiding the regulation of the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes [56][57].

ORF7a generates a dysfunctional deacidified lysosome; therefore, autophagosomal degradation is interrupted and the virus can exit the host cell [55].

Nsp15 modulates autophagy regulation hypothetically by interfering with the mTOR pathway, in this way facilitating SARS-CoV-2 replication [55].

Non-structural protein NSP6 interacts with autophagy in different ways. It can join ER membranes, stimulating the rearrangement of its membranes and facilitating phagophore formation. This is another example of how SARS-CoV-2 uses the autophagy machinery to form DMVs to hide from the immune system and to replicate RNA. Moreover, it was found that viral protein NSP6 impairs autophagic flux, inhibiting autophagy at a late stage and impairing lysosomal acidification by targeting ATP6AP1, a vacuolar ATPase proton pump component. Consequently, the inflammasome is activated through NLRP3. To confirm that NSP6 elicits pyroptosis, Sun and colleagues experimentally overexpressed NSP6 and found that NLRP3/ASC Caspase-1-dependent activation released IL1β and IL18 in lung epithelial cells, thus being a crucial factor in viral pathogenicity [58].

Clinical Implication

Autophagy would be involved in the entry, endo, and release, as well as the transcription and translation of the viral particles in the host cell [59] (He et al. 2022). Also, autophagy could be involved in the systemic inflammatory response and post-COVID-19 syndrome. Selective autophagy, specially mitophagy, was reported to be induced by SARS-Covid2 proteins, modulating inflammatory response. Secretory autophagy would also be involved in the development of the thrombotic immune-inflammatory syndrome seen in a significant number of COVID-19 clinical courses that lead to severe illness and even death.

However, autophagy not only relates to SARS-CoV2 infection by participating in its viral replication cycle. Studies suggest that, surprisingly, reciprocal dysregulation of autophagy by the viral infection itself would be one of the mechanisms of viral survival and tissue damage, given the antimicrobial functions of autophagy, aiding with viral clearance through xenophagy, and its immunological role in battling infection and regulating excessive inflammation [60] (Deretic 2021). Autophagy’s role as a balancer of beneficial and detrimental effects of immunity and inflammation becomes disrupted by viral effects over autophagy’s complex machinery.(Deretic 2021; Levine et al, 2011) [60][61]. Dysregulation of autophagy could imply disinhibition of different molecular processes stimulating the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and interleukins. These mediators favor an exaggerated inflammatory response overall, leading to a thrombotic immunoinflammatory state that correlates with a more severe clinical illness of COVID-19. In fact, one of the described cargos of unconventional autophagy-associated secretion pathways is the export of cytosolic protein IL1β, a proinflammatory cytokine, which has a central role in inducing pro-inflammatory signaling (Ponpuak et al. 2015) [62]. A possible link between this process and the cytokine storm that characterizes the immunoinflammatory state seen in patients with severe COVID-19 could be further explored.

Consequently, identifying different autophagic biomarkers could help correlate with severity of illness, and thus work as a biological marker for prognosis of disease. Many viruses induce direct and indirect mechanisms explaining most of the short-term complications of the disease have correlations with alterations in autophagy. Long-term post-COVID syndromes may be also related to dysfunctional autophagy. Besides, the association between interindividual markers of short- and long-term prognosis and dysfunctional autophagy offers many gaps for further investigation. More research is needed to clarify the involvement of these abnormalities in disease infection and clinical evolution.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms24054928

References

- WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 31 August 2022) . World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Retrieved 2023-7-22

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.-M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.-G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.-W.; Tian, J.-H.; Pei, Y.-Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. . Nature 2020, 579, 265–269.. Retrieved 2023-7-22

- Yoshimoto, F.K. The Proteins of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2 or n-COV19), the Cause of COVID-19. Protein J. 2020, 39, 198–216. . Protein J. 2020, 39, 198–216.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Lv, Z.; Cano, K.E.; Jia, L.; Drag, M.; Huang, T.T.; Olsen, S.K. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Proteases for COVID-19 Antiviral Development. Front. Chem. 2022, 9, 35186898. . Front. Chem. 2022, 9, 35186898. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Thomas, S. Mapping the Nonstructural Transmembrane Proteins of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. J. Comput. Biol. 2021, 28, 909–921. . J. Comput. Biol. 2021, 28, 909–921. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Shojaei, S.; Suresh, M.; Klionsky, D.J.; Labouta, H.I.; Ghavami, S. Autophagy and SARS-CoV-2 infection: A possible smart targeting of the autophagy pathway. Virulence 2020, 11, 805–810. . Virulence 2020, 11, 805–810. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Grasso, D.; Renna, F.J.; Vaccaro, M.I. Initial Steps in Mammalian Autophagosome Biogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 146 . Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 146. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Yu, G.; Klionsky, D.J. Life and Death Decisions—The Many Faces of Autophagy in Cell Survival and Cell Death. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 866. . Biomolecules 2022, 12, 866.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy: From phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 931–937 . Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 931–937. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Glick, D.; Barth, S.; MacLeod, K.F. Autophagy: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Pathol. 2010, 221, 3–12. . J. Pathol. 2010, 221, 3–12.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Debnath, J.; Leidal, A.M. Secretory autophagy during lysosome inhibition (SALI). Autophagy 2022, 18, 1–2. . Autophagy 2022, 18, 1–2. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Takeshita, F.; Kobiyama, K.; Miyawaki, A.; Jounai, N.; Okuda, K. The non-canonical role of Atg family members as suppressors of innate antiviral immune signaling. Autophagy 2008, 4, 67–69. . Autophagy 2008, 4, 67–69.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Dahmane, S.; Shankar, K.; Carlson, L.-A. A 3D view of how enteroviruses hijack autophagy. Autophagy, 19:7, 2156-2158 . Autophagy, 19:7, 2156-2158. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Morita, K.; Hama, Y.; Izume, T.; Tamura, N.; Ueno, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Sakamaki, Y.; Mimura, K.; Morishita, H.; Shihoya, W.; et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen identifies TMEM41B as a gene required for autophagosome formation. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 3817–3828. . J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 3817–3828.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Mohamud, Y.; Xue, Y.C.; Liu, H.; Ng, C.S.; Bahreyni, A.; Jan, E.; Luo, H. The papain-like protease of coronaviruses cleaves ULK1 to disrupt host autophagy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 540, 75–82. . Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 540, 75–82.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Gassen, N.C.; Papies, J.; Bajaj, T.; Emanuel, J.; Dethloff, F.; Chua, R.L.; Trimpert, J.; Heinemann, N.; Niemeyer, C.; Weege, F.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-Mediated Dysregulation of Metabolism and Autophagy Uncovers Host-Targeting Antivirals. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3818. . Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3818.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.-L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192. . Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Moy, R.H.; Gold, B.; Molleston, J.M.; Schad, V.; Yanger, K.; Salzano, M.-V.; Yagi, Y.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Stanger, B.Z.; Soldan, S.S.; et al. Antiviral Autophagy Restricts Rift Valley Fever Virus Infection and Is Conserved from Flies to Mammals. Immunity 2013, 40, 51–65 . Immunity 2013, 40, 51–65.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Kliche, J.; Kuss, H.; Ali, M.; Ivarsson, Y. Cytoplasmic short linear motifs in ACE2 and integrin β 3 link SARS-CoV-2 host cell receptors to mediators of endocytosis and autophagy. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, 665. . Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, 665.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Scudellari, M. How the coronavirus infects cells and why Delta is so dangerous. Nature 2021, 595, 640–644. . Nature 2021, 595, 640–644. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Khade, S.M.; Yabaji, S.M.; Srivastava, J. An update on COVID-19: SARS-CoV-2 life cycle, immunopathology, and BCG vaccination. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 51, 650–658. . Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 51, 650–658. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Cuervo, A.M.; Dice, J.F. A Receptor for the Selective Uptake and Degradation of Proteins by Lysosomes. Science 1996, 273, 501–503. . Science 1996, 273, 501–503.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Iqbal, H.M.; Romero-Castillo, K.D.; Bilal, M.; Parra-Saldivar, R. The Emergence of Novel-Coronavirus and its Replication Cycle—An Overview. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 14, 13–16. . J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 14, 13–16.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Li, W.-W.; Li, J.; Bao, J.-K. Microautophagy: Lesser-known self-eating. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011, 69, 1125–1136. . Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011, 69, 1125–1136. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Ghosh, S.; Dellibovi-Ragheb, T.A.; Kerviel, A.; Pak, E.; Qiu, Q.; Fisher, M.; Takvorian, P.M.; Bleck, C.; Hsu, V.W.; Fehr, A.R.; et al. β-Coronaviruses Use Lysosomes for Egress Instead of the Biosynthetic Secretory Pathway. Cell 2020, 183, 1520–1535.e4. . Cell 2020, 183, 1520–1535.e4. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Nakatogawa, H.; Suzuki, K.; Kamada, Y.; Ohsumi, Y. Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: Lessons from yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 458–467. . Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 458–467.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Lahiri, V.; Metur, S.P.; Hu, Z.; Song, X.; Mari, M.; Hawkins, W.D.; Bhattarai, J.; Delorme-Axford, E.; Reggiori, F.; Tang, D.; et al. Post-transcriptional regulation of ATG1 is a critical node that modulates autophagy during distinct nutrient stresses. Autophagy 2021, 18, 1694–1714. . Autophagy 2021, 18, 1694–1714.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Geng, J.; Klionsky, D.J. The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. EMBO Rep. 2008, 9, 859–864 . EMBO Rep. 2008, 9, 859–864. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Dooley, H.C.; Razi, M.; Polson, H.E.; Girardin, S.E.; Wilson, M.I.; Tooze, S.A. WIPI2 Links LC3 Conjugation with PI3P, Autophagosome Formation, and Pathogen Clearance by Recruiting Atg12–5-16L1. Mol. Cell 2014, 55, 238–252. . Mol. Cell 2014, 55, 238–252. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Ropolo, A.; Grasso, D.; Pardo, R.; Sacchetti, M.L.; Archange, C.; Lo Re, A.; Seux, M.; Nowak, J.; Gonzalez, C.D.; Iovanna, J.L.; et al. The Pancreatitis-induced Vacuole Membrane Protein 1 Triggers Autophagy in Mammalian Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 37124–37133. . J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 37124–37133.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Nascimbeni, A.C.; Giordano, F.; Dupont, N.; Grasso, D.; Vaccaro, M.I.; Codogno, P.; Morel, E. ER–plasma membrane contact sites contribute to autophagosome biogenesis by regulation of local PI 3P synthesis. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 2018–2033. . EMBO J. 2017, 36, 2018–2033. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Geng, J.; Klionsky, D.J. The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. EMBO Rep. 2008, 9, 859–864. . EMBO Rep. 2008, 9, 859–864.. Retrieved 2023-7-22

- Hama, Y.; Morishita, H.; Mizushima, N. Regulation of ER-derived membrane dynamics by the DedA domain-containing proteins VMP1 and TMEM41B. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e53894 . EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e53894. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Itakura, E.; Mizushima, N. Syntaxin 17. Autophagy 2013, 9, 917–919. . Autophagy 2013, 9, 917–919.. Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Shaid, S.; Brandts, C.H.; Serve, H.; Dikic, I. Ubiquitination and selective autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2012, 20, 21–30. . Cell Death Differ. 2012, 20, 21–30.. Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Bauckman, K.A.; Owusu-Boaitey, N.; Mysorekar, I.U. Selective autophagy: Xenophagy. Methods 2015, 75, 120–127. . Methods 2015, 75, 120–127.. Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Leidal, A.M.; Debnath, J. Emerging roles for the autophagy machinery in extracellular vesicle biogenesis and secretion. FASEB BioAdv. 2021, 3, 377–386. . FASEB BioAdv. 2021, 3, 377–386. . Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Simons, P.; Derek, A.; Rinaldi, D.A.; Bondu, V.; Kell, A.M.; Bradfute, S. Integrin Activation Is an Essential Component of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20398. . Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20398.. Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Mészáros, B.; Sámano-Sánchez, H.; Alvarado-Valverde, J.; Calyševa, J.; Mart ˇ ínez-Pérez, E.; Alves, R.; Shields, D.C.; Kumar, M.; Rippmann, F.; Chemes, L.B.; et al. Short linear motif candidates in the cell entry system used by SARS-CoV-2 and their potential therapeutic implications. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, 665. . Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, 665. . Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Gomes, C.P.; Fernandes, D.E.; Casimiro, F.; da Mata, G.F.; Passos, M.T.; Varela, P.; Mastroianni-Kirsztajn, G.; Pesquero, J.B. Cathepsin L in COVID-19: From Pharmacological Evidences to Genetics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 589505. . Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 589505.. Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Hoffmann, H.H.; Sánchez-Rivera, F.J.; Schneider, W.M.; Luna, J.M.; Soto-Feliciano, Y.M.; Ashbrook, A.W.; Le Pen, J.; Leal, A.A.; Ricardo-Lax, I.; Michailidis, E.; et al. Functional interrogation of a SARS-CoV-2 host protein interactome identifies unique and shared coronavirus host factors. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 267–280. . Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 267–280.. Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Peacock, T.P.; Goldhill, D.H.; Zhou, J.; Baillon, L.; Frise, R.; Swann, O.C.; Kugathasan, R.; Penn, R.; Brown, J.C.; Sanchez-David, R.Y.; et al. The furin cleavage site in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is required for transmission in ferrets. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 899–909. . Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 899–909.. Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Smieszek, S.P.; Przychodzen, B.P.; Polymeropoulos, M.H. Amantadine disrupts lysosomal gene expression: A hypothesis for COVID19 treatment. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 106004. . Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 106004. . Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Qu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Hu, G.; Liu, C.; Li, J.; Ren, S.; Xiao, M.Z.X.; et al. ORF3a-Mediated Incomplete Autophagy Facilitates Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 Replication. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 716208. . Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 716208.. Retrieved 2023-7-27

- Schneider, W.M.; Luna, J.M.; Hoffmann, H.-H.; Sánchez-Rivera, F.J.; Leal, A.A.; Ashbrook, A.W.; le Pen, J.; Ricardo-Lax, I.; Michailidis, E.; Peace, A.; et al. Genome-Scale Identification of SARS-CoV-2 and Pan-coronavirus Host Factor Networks. Cell 2021, 184, 120–132.e14. . Cell 2021, 184, 120–132.e14. . Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Trimarco, J.D.; Heaton, B.E.; Chaparian, R.R.; Burke, K.N.; Binder, R.A.; Gray, G.C.; Smith, C.M.; Menachery, V.D.; Heaton, N.S. TMEM41B is a host factor required for the replication of diverse coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009599. . PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009599. . Retrieved 2023-7-27

- Ji, M.; Li, M.; Sun, L.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Qu, W.; Xue, H.; et al. VMP1 and TMEM41B are essential for DMV formation during β-coronavirus infection. J. Cell Biol. 2022, 221, e202112081. . J. Cell Biol. 2022, 221, e202112081.. Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Scutigliani, E.M.; Kikkert, M. Interaction of the innate immune system with positive-strand RNA virus replication organelles. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2017, 37, 17–27 . Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2017, 37, 17–27. Retrieved 2023-7-27

- Sargazi, S.; Sheervalilou, R.; Rokni, M.; Shirvaliloo, M.; Shahraki, O.; Rezaei, N. The role of autophagy in controlling SARS-CoV-2 infection: An overview on virophagy-mediated molecular drug targets. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 1, 1599–1612. . Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 1, 1599–1612. . Retrieved 2023-7-27

- Kim, J.-K.; Park, M.J.; Lee, H.W.; Lee, H.S.; Choi, S.R.; Song, Y.R.; Kim, H.J.; Park, H.-C.; Kim, S.G. The relationship between autophagy, increased neutrophil extracellular traps formation and endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 197, 189–197. . Clin. Immunol. 2018, 197, 189–197.. Retrieved 2023-7-27

- Yang, B.; Jia, Y.; Meng, Y.; Xue, Y.; Liu, K.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Cui, K.; Shang, L.; et al. SNX27 suppresses SARS-CoV-2 infection by inhibiting viral lyso-some/late endosome entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2117576119. . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2117576119.. Retrieved 2023-7-27

- Yuen, C.; Wong, W.; Mak, L.; Wang, X.; Chu, H.; Yuen, K.; Kok, K. Suppression of SARS-CoV-2 infection in ex-vivo human lung tissues by targeting class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 93, 2076–2083. . J. Med. Virol. 2020, 93, 2076–2083. . Retrieved 2023-7-27

- Li, F.; Li, J.; Wang, P.-H.; Yang, N.; Huang, J.; Ou, J.; Xu, T.; Zhao, X.; Liu, T.; Huang, X.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike promotes inflammation and apoptosis through autophagy by ROS-suppressed PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166260 . Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166260. Retrieved 2023-7-26

- Liang, S.; Wu, Y.-S.; Li, D.-Y.; Tang, J.-X.; Liu, H.-F. Autophagy in Viral Infection and Pathogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 766142. . Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 766142. . Retrieved 2023-7-26

- Koepke, L.; Hirschenberger, M.; Hayn, M.; Kirchhoff, F.; Sparrer, K.M. Manipulation of autophagy by SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2659–2661. . Autophagy 2021, 17, 2659–2661. . Retrieved 2023-7-27

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Pei, R.; Mao, B.; Zhao, Z.; Li, H.; Lin, Y.; Lu, K. The SARS-CoV-2 protein ORF3a inhibits fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 31. . Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 31.. Retrieved 2023-7-26

- Miao, G.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Ji, M.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Y. ORF3a of the COVID-19 virus SARS-CoV-2 blocks HOPS complex-mediated assembly of the SNARE complex required for autolysosome formation. Dev. Cell. 2021, 22, 427–442.e5. . Dev. Cell. 2021, 22, 427–442.e5.. Retrieved 2023-7-23

- Yu, Y.; Sun, B. Autophagy-mediated regulation of neutrophils and clinical applications. Burn. Trauma 2020, 8, tkz001. . Burn. Trauma 2020, 8, tkz001.. Retrieved 2023-7-26

- He, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Shi, Y.; Xia, D.; Shen, H.-M. Friend or Foe? Implication of the autophagy-lysosome pathway in SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4690–4703. . Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4690–4703.. Retrieved 2023-7-26

- Deretic, V. Autophagy in Inflammation, Infection, and Immunometabolism. Immunity 2021, 54, 437–453. . Immunity 2021, 54, 437–453.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Levine B. Mizushima N. Virgin H.W. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature. 2011; 469: 323-335. . Nature. 2011; 469: 323-335.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Ponpuak, M.; Mandell, M.A.; Kimura, T.; Chauhan, S.; Cleyrat, C.; Deretic, V. Secretory autophagy. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 35, 106–116. . Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 35, 106–116.. Retrieved 2023-7-25

- Smieszek, S.P.; Przychodzen, B.P.; Polymeropoulos, M.H. Amantadine disrupts lysosomal gene expression: A hypothesis for COVID19 treatment. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 106004. . Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 106004. . Retrieved 2023-7-25