Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Immunology

Proteoglycan 4 (PRG4) is a mucinous glycoprotein secreted by synovial fibroblasts and superficial zone chondrocytes, released into synovial fluid, and adsorbed on cartilage and synovial surfaces. PRG4′s roles include cartilage boundary lubrication, synovial homeostasis, immunomodulation, and suppression of inflammation. PRG4 supplementation may offer a new therapeutic option for gout.

- PRG4

- lubricin

- gout

1. Introduction

The pathophysiology of gout, the most common cause of inflammatory arthritis, includes intersections between genetics, urate homeostasis, innate immunity, and diseases of metabolism, and renal and cardiovascular function [1,2,3]. Urate is particularly limited in its solubility in joint tissues. Additionally, sustained hyperuricemia is a primary risk factor for deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in synovial joints, and a variety of soft tissues including bursae and tendons [2,3,4]. Inflammatory joint disease in gout is chronic, and characteristically punctuated clinically by bouts of acute and excruciatingly painful arthritis and soft tissue inflammation.

Acute inflammation in gout is driven via recognition of urate crystals by tissues’ monocytes/macrophages and their subsequent phagocytosis [5,6]. Activation of the NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes in tissue phagocytes underlies their acute response to urate crystals, resulting in the recruitment of pro-caspase-1 and its conversion to active caspase-1 [6]. Active caspase-1 converts pro-interleukin-1 beta (pro-IL-1β) to mature IL-1β, which drives inflammation in gout [4]. Synovium is comprised of a surface layer, the intima and an underlying subintima [7,8]. The intima of normal synovium is one to three cell layers thick, with two cell types: fibroblast-like synoviocytes and macrophages [7,8]. Synovial macrophages comprise heterogenous populations whose functions include the clearance of cell debris and foreign bodies, tissue immune surveillance, and the resolution of inflammation [9,10]. Importantly, cartilage-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) activate macrophages, and this contributes to the pathophysiology of synovitis [11].

2. Proteoglycan 4 (PRG4)/Lubricinx

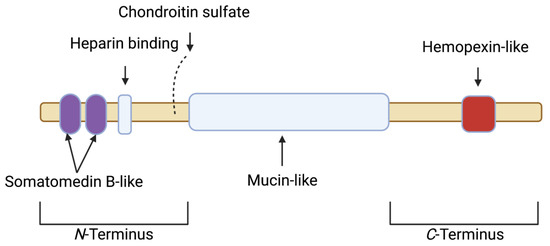

The PRG4 gene is alternatively spliced and is responsible for the mucinous glycoproteins lubricin and superficial zone protein (SZP). Lubricin is secreted by synovial type B fibroblasts, and SZP by superficial zone chondrocytes [12,13,14,15]. PRG4 is a major component of synovial fluid (SF) and is localized on the surface of articular cartilage, where it functions as a boundary lubricant at near-zero sliding speeds and prevents cell and protein adhesions [13,16,17,18]. The boundary-lubricating property of PRG4 prevents friction-induced mitochondrial dysregulation and chondrocyte apoptosis [19,20]. PRG4 is also found in the synovium [21]. The full length synovial form of PRG4/lubricin has a semi-rigid structure. The protein core has 1404 amino acids with N and C termini and a central mucin domain that is heavily glycosylated via O-linked β(1–3) Gal-GalNac oligosaccharides (which account for ~50% of the mucin weight) and is responsible for its boundary-lubricating function [16,22] (Figure 1). The globular N- and C-termini of PRG4 may be involved in multiple biological functions [16]. In the N-terminus, there is a heparin-binding site, a chondroitin sulfate chain, and a somatomedin B-like domain [15,16]. The C-terminus contains a hemopexin-like domain [15,16]. In both domains, PRG4 has greater than 40% sequence similarity with vitronectin, though PRG4 has a unique repeating motif of KEPAPTT in which O-glycosylations are found [16]. Either the N- or C-terminus or both mediate PRG4’s anchoring to surfaces, which results in a brush-like conformation that provides optimal boundary lubrication [23]. The N-terminus is also the site of disulfide bonding, wherein PRG4 exists as monomers, dimers, and multimers, with improved boundary lubrication observed with multimeric PRG4 [24,25]. The concentration of PRG4 is normally high in SF (200 to 400 μg/mL) [26].

Figure 1. Schematic depicting the various motifs within the full length synovial 1404 amino acid proteoglycan 4 (PRG4) polypeptide. The N-terminus contains a somatomedin B-like domain, a heparin binding site and a chondroitin sulfate chain. The N-terminus is also the site for the disulfide bonding of PRG4 monomers. The central domain is mucin-like, and is responsible for boundary lubrication. The C-terminus contains a hemopexin-like domain.

The loss of function mutation in PRG4 is evident in the autosomal recessive disease camptodactylyl-arthropathy-coxa vara-pericarditis (CACP), a rare juvenile onset arthropathy [21,27]. The murine Prg4 knockout model displays key features of CACP disease, and the joints of Prg4 null animals exhibit synovial inflammation, hyperplasia, and fibrosis in addition to cartilage surface damage and chondrocyte apoptosis, which may not be completely reversed by Prg4 re-expression [21,28,29,30]. Human studies that have examined PRG4 SF levels in different cohorts of joint injuries, moderate OA, and advanced OA have reported either a decrease, no change, or an increase in SF PRG4 levels in reference to healthy subjects [31]. Studies that reported a decrease in SF PRG4 levels were more likely to include patients with anterior cruciate ligament or meniscal tears within one year of injury, whereas four out of five studies that reported an increase in SF PRG4 levels included patients with advanced OA [31]. It is unclear whether the different assays used in these studies to quantify SF PRG4 could differentiate between full-length and degraded protein.

Multiple studies in animals showed that cartilage, synovial PRG4 expression, or a combination thereof were reduced in mouse, rat and guinea pig models of naturally occurring and posttraumatic OA (PTOA) [32,33,34,35,36]. Using in vitro models, PRG4 expression in chondrocytes and synoviocytes was shown to be reduced by IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and increased by transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) [37,38,39,40,41]. Furthermore, PRG4 is proteolytically degraded by multiple enzymes, e.g., elastase, and cathepsins B and G [36,42]. A summary of studies that showcase the disease-modifying effects of native and recombinant PRG4 in pre-clinical PTOA models is presented in Table 1 [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. In addition, Prg4 gene therapy is efficacious in mitigating murine age and injury-related OA development [51,52,53].

Table 1. In vivo efficacy of native and recombinant PRG4/lubricin in pre-clinical models of post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA) and the pharmacokinetic profile of recombinant human PRG4 as a potential biologic therapeutic for PTOA.

| Study | Model and Treatment(s) | Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Flannery et al. [43] | Rat meniscectomy; I.A. recombinant human lubricin construct with one third KEPAPTT-like sequence 3× week or 1× week for 4 weeks. | Both treatments reduce cartilage degeneration and total joint scores. |

| Jay et al. [44] | Rat ACLT; I.A. recombinant full-length lubricin, HSL or HSFL 2× week for 4 weeks. | HSL reduces cartilage degeneration scores; HSL and HSFL reduce uCTXII levels, and all lubricins enhance aggrecan synthesis. |

| Teeple et al. [45] | Rat ACLT; I.A. hyaluronan, HSFL or hyaluronan + HSFL 2× week for 4 weeks. | HSFL alone or hyaluronan + HSFL reduce radiographic and cartilage degeneration scores with no effect by hyaluronan alone. |

| Jay et al. [46] | Rat ACLT; I.A. HSL once on day 7 post-surgery and analysis at 10 weeks. | HSL enhances aggrecan synthesis, reduces uCTXII levels, and improves weight bearing in injured joints. |

| Elsaid et al. [47] | Rat ACLT + forced exercise; HSFL on day 7 post-surgery and analysis at 5 weeks | Forced exercise aggravates cartilage damage and increases uCTXII excretion; HSFL treatment protects against ACLT + forced exercise cartilage damage. |

| Elsaid et al. [48] | Rat ACLT; I.A. IL-1ra 4× week for one week; I.A. IL-1ra + rhPRG4 once on day 7 post-surgery and analysis at 5 weeks. | IL-1ra reduces synovial inflammation and increases lubricin levels in SF; rhPRG4 and IL-1ra synergistically reduce chondrocyte apoptosis. |

| Waller et al. [49] | Minipig DMM; I.A. rhPRG4, hyaluronan or rhPRG4 + hyaluronan 3× week for one week and analysis at 26 weeks post-surgery. | rhPRG4 reduces medial tibial plateau macroscopic cartilage damage, uCTXII levels, SF, and serum IL-1β. |

| Hurtig et al. [50] | Minipig ACLT; I.A. 131 I-rhPRG4 once with analysis at 10 min, 24, 72 h, 6, 13 and 20 days. | rhPRG4 joint elimination kinetics follows a two-compartment model with t1/2β of 4.81 days. |

ACLT: anterior cruciate ligament transection; DMM: destabilization of the medial meniscus; HSL: human synoviocyte lubricin; HSFL: human synovial fluid lubricin; I.A.: intra-articular; IL-1β; interleukin-1 beta; IL-1ra: interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; rhPRG4: recombinant human proteoglycan 4; SF: synovial fluid; uCTXII: urinary C-terminal crosslinked telopeptide type II collagen.

Biologically, PRG4 binds transmembrane CD44 receptors and competes with high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid (Hyaluronan) to do so. As a consequence of preferentially binding CD44, PRG4 reduces the mitogen-activated proliferation of mouse Prg4−/− synoviocytes and human synoviocytes from patients with OA and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [54,55]. In OA synoviocytes, recombinant human PRG4 (rhPRG4) treatment reduces NF-κB nuclear translocation via inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation [55], with downstream reduction of the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP1, MMP3, MMP9, MMP13) and cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 [55]. PRG4 also binds to the toll-like receptor (TLR) family of pattern recognition receptors [56,57], and PRG4 suppresses activation of TLR2 and TLR4 receptors by DAMPs in SF aspirates from patients with OA [57].

PRG4 plays a significant role in regulating synovial macrophages. In Prg4-deficient mice, macrophages accumulate in synovial tissues with age [58], while the tissue resident fraction is reduced. Total macrophages in the synovium skew to a predominantly CD86+ pro-inflammatory phenotype, and away from the CD206+ anti-inflammatory phenotype [58]. Prg4 re-expression in mice reduces total macrophages in synovial tissues and re-establishes homeostasis with an enrichment in anti-inflammatory CD206+ synovial macrophages [58]. Furthermore, Prg4 deficiency appears to prime acute synovitis, as demonstrated by enhanced inflammatory macrophage recruitment [58]. Interestingly, synovial macrophage depletion in otherwise Prg4-deficient mice reduces synovial hyperplasia and synovial fibrosis [58]. These collective observations support PRG4’s immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory roles in the joint.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/gucdd1030012

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!