Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) catalyzes the degradation of heme molecules releasing equimolar amounts of biliverdin, iron and carbon monoxide. Its expression is induced in response to stress signals such as reactive oxygen species and inflammatory mediators with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive consequences for the host. Interestingly, several intracellular pathogens responsible for major human diseases have been shown to be powerful inducers of HO-1 expression in both host cells and in vivo. Studies have shown that this HO-1 response can be either host detrimental by impairing pathogen control or host beneficial by limiting infection induced inflammation and tissue pathology. These properties make HO-1 an attractive target for host-directed therapy (HDT) of the diseases in question, many of which have been difficult to control using conventional antibiotic approaches.

- heme oxygenase-1

- inflammation

- immune response

- infectious disease

- intracellular pathogens

- host directed therapy

Note: The following contents are extract from your paper. The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

Heme oxygenases (HOs) are highly conserved enzymes that are present in a large number of species as evolutionary distant as algae and humans [1]. The mechanisms associated with the catabolism of heme by the heme oxygenase system were first demonstrated in 1968 by Tenhunen et al. utilizing microsomes from rat livers [2]. HO itself was first purified in 1977 by Maines et al. [3] and almost 10 years later, in 1986, the same author identified two isoforms of the enzyme in rat liver microsomes: heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), whose expression in liver was upregulated in response to in vivo treatment of rats with chemicals, and heme oxygenase-2 (HO-2), whose constitutive expression remained unaltered by in vivo challenge with the same compounds [4]. In parallel, different groups identified a 32 kDa stress-responsive protein, whose expression was highly upregulated in different cell lines in response to challenges such as hyperthermia, heavy metals and oxidative stress. This protein, referred to as Heat-Shock Protein 32 (HSP-32) at that time [5–10], was later shown to be identical to HO-1 [11,12]. A third isoform, heme oxygenase-3 (HO-3), was characterized in 1997 in a number of different rat tissues, but displayed poor enzymatic activity [13] and its physiological role remains largely uncharacterized to this day. A later study in 2004 failed to isolate rat HO-3 protein and questioned the existence of its gene speculating that the originally identified HO-3 may in fact represent the product of pseudogenes derived from HO-2 transcripts [14].

The main function of HO-1 and HO-2 is to catalyze the degradation of heme molecules, providing the rate-limiting step for this reaction, which consumes three molecules of O2 and seven electrons resulting in the release of equimolar amounts of carbon monoxide (CO), ferrous iron (Fe2+) and biliverdin [15]. Both HO-1 and HO-2 have a conserved heme catalytic domain, while HO-2 has two additional heme-binding regions, which are associated with regulation of its activity, but are devoid of enzymatic function [16]. It has recently been determined that these regions play a role in the transfer of heme molecules to the catalytic site [17]. After heme binds to HO, the first step of the degradation reaction uses an O2 molecule and electrons donated by NADPH–cytochrome-P450-reductase to oxidize heme into α-meso-hydroxyheme, releasing a water molecule. α-meso-hydroxyheme further reacts with another oxygen molecule resulting in the release of verdoheme and CO. A subsequent reaction step consumes a third O2 molecule and again electrons donated by NADPH–cytochrome-P450-reductase, converting verdoheme into biliverdin and ferrous iron [18].

In homeostatic conditions, HO-1 is detected mainly in the liver and spleen, while HO-2 is stably expressed in most organs with higher levels being found in testes, spleen, liver, kidney, cardiovascular and central nervous systems [19,20]. Unlike HO-2, whose expression remains unchanged after challenge with different stressors [16], HO-1 expression is induced in cells from most tissues in response to oxidative stress and inflammation and is particularly highly upregulated in macrophages affected by infection with intracellular microorganisms [21,22].

Heme and the products of its degradation can influence the outcome of infection with intracellular pathogens in different ways. Heme can be used as a source of nutrient iron for replication by intracellular pathogens, directly enhancing their survival and growth inside their host cell niches including phagocytes [23]. On the other hand, the CO and bilverdin products of heme degradation can exert both pro and anti-inflammatory roles, resulting in the suppression of immune responses and control of pathogen replication, or in the regulation of pathogenesis and inflammation-driven tissue damage [24,25]. In the center of this process lies the inducible HO-1 isoform, which by mediating heme degradation can markedly influence the outcome of infection with intracellular pathogens through the diverse effects of it enzymatic products [26]. Due to its close association with the inflammatory process, numerous studies have evaluated the use of HO-1 as a biomarker for severity or prognosis of such infectious diseases. This work has been accompanied by mechanistic studies examining the role of HO-1 in both host resistance and pathogenesis employing genetically deficient animals or pharmacological inhibitors or inducers of the enzyme’s activity or expression as investigative tools.

2. Mechanisms of Induction of HO-1 Expression

HO-1 is constitutively expressed at high levels in the liver and spleen reticuloendothelial systems, especially in macrophages that engulf senescent red blood cells and promote, through the action of HO-1, the recycling of iron from heme derived from hemoglobin [27]. Heme can also originate from degradation of other heme containing proteins such as myoglobin, cytochromes and several peroxidases, catalases and oxidases [28], or can be internalized from the extracellular compartment, where free heme and hemoglobin molecules are scavenged by the acute phase proteins hemopexin and haptoglobin respectively and then endocytosed via interaction with the receptors CD91 (heme/hemopexin complex) and CD163 (hemoglobin/haptoglobin complex) [29,30]. Heme is transported from the phagolysosomes to cytosol by the heme responsive gene-1 (HRG-1 or SLC48A1) transporter [31,32] and later to the nucleus where it can directly induce HO-1 expression by playing a pivotal role in a sequence of events that culminate in HMOX1 gene transcription as described below. The mechanisms involved in its transport to the nucleus, however, are not completely understood, although there is evidence identifying the enzyme biliverdin reductase as a mediator in this process [33].

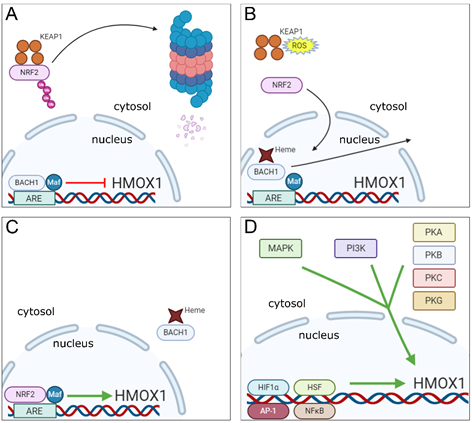

The HMOX1 gene contains in its promoter region a motif known as Maf Recognition Element (MARE) or Antioxidant Response Element (ARE), which is recognized by a dimer composed of the BTB and CNC Homology 1 (BACH1) transcription factor together with one of 3 small Maf oncogenic proteins (MafF, MafG or MafK). Under normal conditions, the BACH1-Maf dimer remains bound to the ARE motif in HMOX1 gene promoter and acts as a repressor of its transcription [34]. However, BACH1 has a heme-binding region, which upon interaction with heme molecules present in the nucleus, promotes dissociation of BACH1 from the Maf protein and from the ARE motif in the HO-1 gene promoter. This event is followed by translocation of BACH1 molecule to the cytoplasm where it undergoes ubiquitination and further degradation by the proteasome [35]. With BACH1 now displaced from the nucleus, Maf forms a dimer with the Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (NRF2) transcription factor, which then binds to the same ARE region and induces HO-1 gene transcription [36,37].

In order to induce HO-1 expression, NRF2 must be activated simultaneously with BACH1 inactivation. This process is driven by electrophilic and oxidative stresses, which occur for example when heightened production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is detected [38,39]. During resting conditions, NRF2 is found in the cytoplasm, associated with the protein Kelch-like ECH-Associated Protein 1 (KEAP1), which promotes NRF2 ubiquitination, resulting in proteasomal degradation of the transcription factor [40]. Upon induction of electrophilic and oxidative stresses, the resulting reactive species will cause modifications in specific cysteine residues present on KEAP1, resulting in inhibition of NRF2 ubiquitination. The transcription factor is then released from KEAP1 and translocated to the nucleus where it will dimerize with small Maf proteins to induce HO-1 gene transcription as described above [41–43].

As already mentioned, oxidative stress is a major inducer of HO-1 expression and is a process closely linked with inflammation [44,45]. However, a number of different signaling pathways and transcription factors triggered by inflammatory mediators, danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) have also been reported to trigger HMOX1 transcription [46,47]. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), tyrosine kinases and protein kinases (PK) A, B, C and G signaling cascades are commonly activated in response to the above mentioned stimuli and are all involved in the induction of HO-1 expression [48–50]. For example, PKC can directly phosphorylate a serine residue located at position 40 on the NRF2 protein, which results in its disruption from KEAP1 thus promoting NRF2 translocation to the nucleus [51]. It has also been reported that NRF2 can be directly phosphorylated at several serine and threonine sites by different MAPKs in vivo. Of note, in that latter case, no effects on NRF2-KEAP1 interaction were observed [52]. Indeed, a number of additional studies have confirmed that MAPK activities can induce NRF2 activation in response to different stimuli [53–56], however, they leave open the possibility that the effect of these enzymes on NRF2 signaling may be indirect.

It is important to note that there are regions in the HO-1 gene promoter that serve as binding sites for other transcription factors apart from NRF2, whose expression can be induced as a result of activation of the same signaling cascades mentioned above, such as heat-shock factors (HSFs), activator protein-1 (AP-1), nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) and hypoxia-induced factor 1 α (HIF1α) [48,57]. These alternative pathways are briefly described below.

In rats, two genomic motifs known as heat shock elements (HSEs) are present in the HO-1 gene promoter that serve as binding sites for HSF and have been shown to play a role in the induction of HO-1 expression in response to hyperthermia [58]. In mouse fibroblasts, deletion of the HSF-1 gene results in marked reduction of HO-1 expression in response to heat shock injury [59]. However, the mechanisms involved in HO-1 induction by the interaction of HSF with HSEs in the HO-1 gene promoter vary among species. For example, HSEs identified in the rat HMOX1 promoter are inactive in humans and mice [48], and therefore, further studies are needed to fully elucidate this putative pathway for HO-1 induction.

The transcription factor AP-1 actually encompasses a family of structurally and functionally related transcription factors composed of dimers made up of members of the Jun (c-Jun, JunB and JunD), Fos (c-Fos, FosB, Fra1 and Fra2), ATF (Atf2, Atf3, Atf4, Atf5, Atf6B, Atf7, BATF, BATF2, BATF3, JDP1 and JDP2) and Maf (c-Maf, MafA, MafB, MafF, MafG and MafK Nrl) DNA-binding protein families [60]. Functional AP-1 binding sites have been identified in promoter regions of mouse, rat and human HO-1 genes [61–63] and studies have demonstrated a role for AP-1 in the induction of HO-1 expression in cells from mice, rats and humans [64–66]. However, the mechanisms through which AP-1 regulates the induction of HO-1 expression are complex and may involve a cooperative interaction between AP-1 subunits and different transcription factors [66–68], including NRF2 [69].

NFκB, similar to AP-1, is a generic term that denotes transcription factors formed by the homo or heterodimerization of components of the Rel family of proteins, namely RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, p52 and p50 [70]. During resting conditions, NFκB is found in the cytoplasm in an inactive state bound to the Inhibitor of NFκB molecule (I-κB). Upon cell stimulation, the transcription factor subunits are released from I-κB (which is phosphorylated by the kinase IKK—I-κB kinase—and further degraded by the proteasome) and translocated to the nucleus, where they bind to promoter regions of specific genes and induce their transcription [71]. Functional binding sites for NFκB were identified in the promoter regions of the HO-1 gene. These sites were found to be involved in the induction of rat HO-1 expression in response to phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) in vitro [72] and also in the NOS2-mediated upregulation of HO-1 expression in mouse cardiac tissue [73].

HIFs are a family of transcription factors whose expression is upregulated in response to low oxygen concentrations. They are composed of a constant subunit (HIF1β) and one of three variable α subunits (HIF1α, HIF2α and HIF3α), which provide the name for the whole heterodimer. Oxygen is used as a cofactor by the enzyme prolyl hydroxylase (PHD), which initiates a process culminating in ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of α subunits. As a consequence, under hypoxic conditions, PHD is held inactive resulting in stabilization of α subunits. This process allows these subunits to dimerize with HIF1β and be translocated to the nucleus to initiate gene transcription [74,75]. HIF1α is by far the best studied of these factors and its expression is highly upregulated during inflammation [76]. Binding sites for HIF1α have been identified in the rat HMOX1 gene approximately 9.5 kilobases upstream of the transcription start site and were shown to be responsible for the induction of HO-1 expression in response to hypoxia in rat aortic vascular muscle cells [77]. Induction of HO-1 transcription in response to direct binding of HIF1α to DNA has also been observed in rat renal medullary interstitial cells as well [78]. Human cells also upregulate HO-1 in response to HIF1α, although direct HO-1 induction by HIF1α binding to the HMOX1 gene was not demonstrated [79].

The existence of multiple pathways for triggering and repressing HO-1 transcription (summarized in Figure 1) is consistent with a central role for the enzyme in responding to a wide variety of inflammatory stimuli and within a range of different host cell types.

Figure 1. Molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of HMOX1 gene transcription. (A) In homeostatic conditions, NRF2 is found in the cytosol of cells bound to KEAP1, which promotes ubiquitination of NRF2 that is further degraded in proteasomes. In the nucleus, the transcription factor BACH1 remains bound in association with a small Maf protein to the ARE region in HMOX1 gene promoter repressing its transcription. (B) Under stress conditions, binding of heme molecules to BACH1 in the nucleus promotes its displacement from the small Maf protein and ARE motif in the HMOX1 gene promoter, while in the cytosol, ROS induce changes in KEAP1 cysteine residues that promote the release of NRF2 and prevents its ubiquitination and degradation. (C) NRF2 is translocated to the nucleus, where it associates to a small Maf protein and binds to the ARE motif in HMOX1 gene promoter inducing its expression, while heme-bound BACH1 is excluded from the nucleus. (D) Signaling cascades involved in the induction of HMOX1 gene expression (MAPK, PI3K and PKA, B, C and G—cytosol) and transcription factors to which recognition motifs were identified in the HMOX1 gene or that were shown to induce HO-1 expression (HIF1α, HSF, AP-1 and NFκB—nucleus).

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/antiox9121205