Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration in the atmosphere is responsible for global warming which in turn causes abrupt climate change and consequently poses a threat to the living organisms in the coming years. CO2 capture and separation are crucial to reduce the CO2 content in the atmosphere. Post-combustion capture is one of the most useful techniques for capturing CO2 due to its practicality and ease of use. For adsorption-driven post-combustion CO2 capture, polymers with large surface area, high volume, and narrow pores are the best solid sorbents. Surface area and pore size of the synthetic porous organic polymers can be precisely tuned for high CO2 capturing capacity. Natural polymers, such as polysaccharides, are less expensive, more plentiful, and can be modified by a variety of methods to produce porous materials and thus can be effectively utilized for CO2 capture. A significant amount of research activities has already been established in this field, especially in the last ten years and are still in progress. In this review, we have introduced the latest developments to the readers about synthetic techniques, post-synthetic modifications and CO2 capture capacities of various biopolymer-based materials and synthetic porous organic polymers (POPs) published in the last five years (2018–2022).

- carbon dioxide capture

- post-combustion

- natural polymer

- synthetic polymer

- Introduction

Elevation of carbon dioxide (CO2) gas concentration in the atmosphere is the major factor contributing to global warming. In recent years, CO2 emissions reached a record level, primarily as a result of the burning of fossil fuels [1]. Carbon capture and storage/sequestration (CCS) is crucial in order to prevent the atmosphere's CO2 concentration from rising. Pre-combustion, post-combustion, oxy-fuel combustion, and direct air capture are the main methods used to capture CO2. Out of these methods, post-combustion capture of CO2 is operationally simple and useful in many industries and power sectors, such as coal-fired power plants [2]. An efficient technique for post-combustion CO2 capture is the adsorption of gas onto the surface of solid material. Polymer and polymer-based materials are discovered to be particularly promising among several forms of solid sorbents. An efficient and very sustainable method of CO2 capture is the use of non-toxic, affordable, and widely available polysaccharide-based biopolymers. Porous biopolymer-based materials are usually prepared by carbonization and physical or chemical activation of the chosen biopolymers [3]. Synthetic porous organic polymers are a viable option of material for post-combustion CO2 capture due to their low density, high porosity, large surface area, and high stability. It is also easy to modify the POPs' surfaces to increase their ability to trap CO2. Porous organic polymers (POPs) are generally synthesized by connecting monomeric units by covalent bonds utilizing various types of reactions. By choosing the right monomers and using synthetic techniques, the pore size and surface characteristics can be precisely adjusted to increase CO2 adsorption capacity and selectivity over other gases [3].

Since CCS is a significant and cutting-edge field of study, a huge number of research articles have been published in the past two decades. Worldwide, there has been a tremendous increase in the development of new POP types and novel porous materials produced from them. Some good review have been published on the applications of POPs towards CCS in the last decade [3–6]. In this scenario, a comprehensive report is needed to inform the readers of the most recent advancements in POP synthesis processes as well as new biopolymer-derived materials and CCS applications. We have compiled the synthetic methods, post-synthetic changes, and CO2 capture capabilities of various biopolymer-based materials and synthetic POPs published in the recent five years (2018-2022) for this aim. We also briefly touched on the elements that affect the selectivity and capacity of CO2 capture.

- Major Types of Polymers and Mechanism of Adsorption of CO2

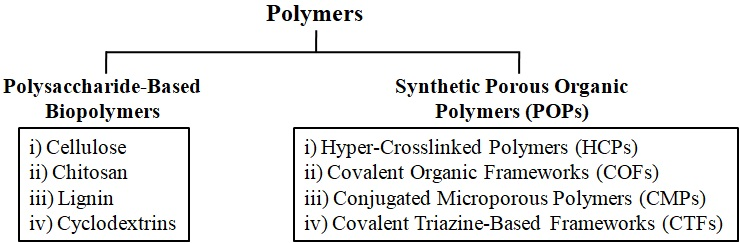

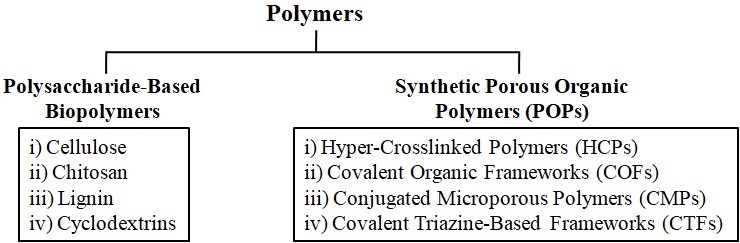

In the capture and storage of CO2, both natural and synthetic polymers are widely used. Figure 1 depicts the main categories of polysaccharide-based biopolymers and synthetic porous organic polymers used in CCS. Polysaccharides that have proven to be highly useful in CO2 capture and storage applications include cellulose, chitosan, lignin, and cyclodextrins. POPs are another large class of synthetic porous materials that have shown excellent potential for CO2 capture and storage. Out of the several POP kinds, hyper-cross-linked polymers (HCPs), conjugated microporous polymers (CMPs), covalent organic frameworks (COFs), and covalent triazine-based frameworks (CTFs) are frequently utilized in CCS [2-4].

Polymers and porous materials derived from them capture CO2 gas by adsorption on the surface. Physical adsorption, also known as physisorption, and chemical adsorption, known as chemisorption, are the two types of adsorption processes. Through non-covalent interactions (Coulombic, Van der Waals, etc.), physisorption takes place on the adsorbent's surface. In this instance, desorption of the gas molecules is a low-energy process. Adsorbents can be reused repeatedly, which is a key benefit of physisorption. On the other hand, reduced selectivity and a low adsorption capacity of the adsorbent at high temperatures are disadvantages. In chemisorptions, gas molecules and the surface of the adsorbent create covalent bonds. On the surface of common adsorbents, there are basic functional groups like amine. Basic functional groups react with acidic CO2 molecules to produce salts. High adsorption capacity and superior selectivity of the adsorbents are chemisorption's main benefits. This process often has energy-intensive sorbent regeneration as a downside [7].

Isosteric heat of adsorption (Qst) value, calculated by fitting adsorption isotherms by using the Clausius–Clapeyron equation, indicates strength of interaction between adsorbents and CO2 molecules. A low Qst value points to a predominance of physisorption, whereas a high Qst value points to a strong interaction between the surface of the material and the gas molecules, resulting to a predominance of chemisorption. Effective separation requires good adsorbents to preferentially absorb CO2 over all other gases. CO2/N2 selectivity is thus a crucial indicator for CO2 capture by adsorbents. Henry's law and the ideal adsorption solution theory (IAST) are used to compute the CO2/N2 selectivity. Additionally significant elements that influence adsorption efficacy are the adsorbents' porosity and surface area. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory is commonly used to assess the surface areas of the adsorbents [8].

Figure 1. Major types of polymers used for CO2 capture and storage

Figure 1. Major types of polymers used for CO2 capture and storage

- Polysaccharide-Based Biopolymers for CO2 Capture

Over years biopolymers are utilized for designing biomaterials for various applications such as packaging materials in the food industry, fuel cells, drug delivery, membrane and medical implants organ preperation, tissue engineering and many more [9–14]. Polysaccharides are cheap and abundant carbohydrate-based biopolymers which has multiple applications [3,15–22]. In studies of CO2 capture and storage, cellulose, chitosan, lignin, and cyclodextrins are some of the most often used polysaccharides due to their wide availability, simplicity of processing, tolerance to structural modifications, and solubility [3]. The following is a summary of applications of these four key types of biopolymers in CCS that have been documented over the last five years.

3.1. Cellulose

Cellulose is a linear polysaccharide consisting of repeated D-glucose units with the formula of (C6H10O5)n. In a recent study, bottom-up ecosystem simulation is coupled with models of cellulosic biofuel production, carbon capture and storage to track ecosystem and supply chain carbon flows for current and future biofuel systems. This approach could have climate mitigation and stabilization potential [20]. Different types of polysaccharides for CO2 capture have been reported by Qaroush et al, describing the reversible reaction between cellulose and CO2, their subsequent dissolution, regeneration and CO2 capturing using functionalised cellulosic materials [3]. One interesting approach for CO2 capture is converting cellulose to sustainable porous carbon materials [21]. Porous carbonaceous materials are usually prepared by carbonization and activation [21]. Carbonization process can be of two types, (i) pyrolytic approach which involves heating the sample at elevated temperatures of 400–1000 °C in an inert atmosphere (e.g., N2, Ar). Several steps included in pyrolytic approach like dehydration, condensation and isomerization, which ultimately eliminates most of the hydrogen and oxygen atoms to form H2O, H2, CH4, and CO gases. Other approach (ii) Hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) is usually performed at moderate temperatures (<300 °C) and advantageous due to reduced energy consumption, sample does not need to be dry and gives carbon-rich hydrochars in high yields. Thus in recent times, the HTC method is considered an energy-saving and environmentally friendly approach for carbonization [21]. Two activation methods are being reported which produce porous carbons with large differences in porosity. In general, physical activation processes create porous carbons with moderate surface areas (1000 m2/g) and narrow micropores that can be beneficial for, e.g., CO2/N2 and CO2/CH4 separation [21]. In contrast, chemical activation significantly increases the surface area (up to >3000 m2/g) and pore volume of the porous carbons which can be useful for gas storage [21]. Here CO2 adsorption capacity of some cellulose-derived materials derived by the carbonization process are discussed. A series of porous carbons derived from commercial cellulose fibres in three steps has been reported by Heo et al. They described that steam molecules played a key role in the pore-opening process and increase in the surface area of the porous carbon materials formed. The cellulose fibres were carbonized under N2 atmosphere followed by physical activation with steam under gauge pressure. Ultramicropores (pore size < 0.8 nm) resulted by physical activation process significantly contributed to the increase in surface areas from 452 to 540 m2/g for pre-activated samples to 599–1018 m2/g for steam-activated samples causing CO2-over-N2 adsorption selectivity and increase in CO2 adsorption capacity by physical adsorption method [22]. In a following study, Zhuo et al. reported a hierarchically porous carbons prepared by carbonization/activation of cellulose aerogels under CO2 and N2 atmosphere with improved surface area and volume for CO2 adsorption. They showed that steam activation is an efficient process to prepare cellulose-based porous carbons with high CO2 adsorption capacities by physisorption [23].

Chemically activated carbonaceous materials have much higher surface areas thus resulting in much higher CO2 adsorption capacities. Chemical activation of cellulose by KOH was reported by Sevilla et al. to design microporous carbon materials with a very high surface area of 2370 m2/g and CO2 adsorption capacity of 5.8 mmol g−1 at 1 bar and 273 K at a high adsorption rate and excellent adsorption recyclability by physisorption mechanism. The material was prepared by hydrothermal carbonization of potato starch, cellulose and eucalyptus sawdust followed by chemical activation using potassium hydroxide [24]. In another study by Xu et al., algae-extracted nanofibrous chemically modified cellulose carbonized under N2 and CO2 atmosphere and activated in CO2 was reported to show significantly higher surface areas (832–1241 m2/g) and higher volumes of ultramicropores (0.24–0.29 cm3/g) for CO2 physisorption [25]. In recent times, cellulose aerogels have also displayed promising applications in carbon storage. A review has been reported by Ho et al. depicting chemical modification of nanocellulose aerogels leading to a large surface area which improved selectivity towards CO2 chemisorption [26]. Kamran et al. utilized hydrothermal carbonization method and chemical activation with acetic acid as an additive, to develop highly porous carbons. These cellulose-based materials displayed high specific surface area (SSA) (1260–3019 m2 g−1), microporosity in the range of 0.21–1.13 cm3 g−1 with CO2 adsorption uptake of 6.75 mmol g−1 and 3.96 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 298 K at 1 bar, respectively, and CO2 selectivity by physisorption mechanism. The carbonaceous material having micropores between 0.68 nm and 1 nm exhibited high CO2 adsorption potential [27].

However non-carbonized cellulose-derived materials have also been reported for efficient CO2 adsorption capacities. In this regard, Wang et al. and Sun et al. have reported that cross-linking of nanocellulose enhances the surface area and CO2 adsorption [28,29]. Amino-functionalization of nanocellulose aerogels although reduced the surface area but still displayed chemisorption of CO2 with a capacity of more than 2 mmol g−1 [26]. In some other reports, cellulose hybrids were designed without any carbonization with inorganic fillers such as silica, zeolite and metal–organic frameworks which improved the surface area and physisorption of CO2 [26]. Sepahvand et al. have designed nano filters by combining cellulose nanofibers (CNF) and chitosan (CS) at varied loading compositions. Increasing the concentration of modified CNFs increases the adsorption rate of CO2 and the highest adsorption of CO2 was showed by 2% modified CNF [30]. In a recent study, epoxy-functionalized polyethyleneimine modified epichlorohydrin-cross-linked cellulose aerogel with rich porous structure and specific surface area in the range of 97.5–149.5 m2/g has been reported by Chen et al. Good adsorption performance by chemisorption mechanism, with a maximum CO2 adsorption capacity of 6.45 mmol g−1 was displayed by the epoxy functionalized cellulose aerogels[31]. Material type and composition, BET surface area (m2 g−1), pore size (nm)/total pore volume (cm3 g−1), mechanism of adsorption, CO2 capture capacity (mmol g−1) and special features of cellulose-based materials have been tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of material type and composition, BET surface area (m2 g−1), pore size (nm)/total pore volume (cm3 g−1), CO2 capture capacity (mmol g−1) and special features of cellulose-based materials.

|

Material Type and Composition |

BET Surface Area (m2 g−1) |

Pore Size (nm)/Total Pore Volume (cm3 g−1) |

CO2 Capture Capacity (mmol g−1) |

Special Features |

Ref |

|

Porous carbons derived from commercial cellulose fibres |

540 and

1018 |

<0.8 nm–/0.234 and

0.429 |

3.776 at 298 K |

CO2-over-N2 adsorption selectivity |

[22] |

|

Carbonized and activated cellulose from cotton linter |

1364 |

1.42 |

3.42 |

- |

[23] |

|

Chemically activated cellulose |

2200–2400 |

1.1 |

4.8 |

CO2-over-N2 adsorption selectivity |

[24] |

|

Algae extracted nanofibrous chemically modified cellulose activated in CO2 |

832–1241 |

0.24–0.29 |

2.29 at 0.15 bar, 5.52 at 1 bar; 273 K |

CO2-over-N2 adsorption selectivity |

[25] |

|

Silica/Cellulose Nanofibril aerogel functionalized with 3-aminopropyl triethoxysilane |

11 |

0.05 |

2.2 at humid condition |

high chemisorption of CO2 with reduced surface area |

[26] |

|

Highly porous cellulose by hydrothermal method and chemical activation using acetic acid as an additive. |

1260–3019 |

0.21–1.13 |

6.75 at 273 K, 1 bar and 3.96 at 298 K, 1 bar |

CO2 selectivity |

[27] |

|

polyethyleneimine-crosslinked cellulose (PCC) aerogel sorbent |

234.2 |

- |

2.31 at 25 ℃ under pure dry CO2 atm |

Adsorption-desorption recyclability |

[28] |

|

Cellulose nanofiber (CNF) surface was functionalized using chitosan (CS), poly [β-(1, 4)-2amino-2-deoxy-Dglucose] |

~360 |

~4 nm |

4.8 |

Increasing the concentration of modified CNFs increases the adsorption rate of CO2 |

[30] |

|

Epoxy-functionalized polyethyleneimine modified epichlorohydrin-cross-linked cellulose aerogel |

97.5–149.5 |

- |

6.45 |

Material showed preferable rigidity and carrying capacity |

[31] |

One important class of nanocellulose-based materials and their subsequent application involves membrane separation of CO2. In this regard, Ansaloni et al. reported micro fibrillated cellulose/Lupamin membrane which showed very good CO2 permeability. However the selectivity of CO2/N2 and CO2/CH4 (in the order of 500 and 350, respectively, for pure micro cellulose) was compromised thus decreasing the overall membrane performance [32]. Venturi et al. later did a systematic study of CO2 permeability by nanocellulose-based membranes under the influence of doping. They designed films by blending the commercial Polyvinylamine solution Lupamin® 9095 (BASF) with Nano Fibrillated Cellulose (NFC). It was reported that, increasing water vapour and a higher presence of Lupamin in the film improved CO2 gas permeability as well as selectivity. NFC content of 70 wt% Lupamin showed a selectivity of 135 for the separation of CO2/CH4 and 218 for CO2/N2 while the maximum permeability in the order of 187 Barrer was reached at 80% RH [33]. In a follow up study by the same group, the addition of l-arginine to a matrix of carboxymethylated nano-fibrillated cellulose (CMC-NFC) resulted in a mobile carrier facilitated transport membrane for CO2 separation. l-arginine (45 wt.% loading) greatly improved CO2 permeability by 7-fold from 29 to 225 Barrer and selectivity with respect to N2 from 55 to 187 compared to pure carboxymethyl nanocellulose matrix [34]. Pure and mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) with polyethylene glycol (PEG), Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and cellulose acetate (CA) has been reported by Hussain et al to capture carbon from natural gas. Membranes of pure CA, CA/PEG blend of different PEG concentrations (5%, 10%, 15%) and CA/PEG/MWCNTs blend of 10% PEG with different MWCNTs concentrations (5%, 10%, 15%) were designed. The CO2/CH4 selectivity is enhanced 8 times for pure membranes containing 10% PEG and 14 times for MMMs containing 10% MWCNTs and in mixed gas experiments, the CO2/CH4 selectivity is increased 13 times for 10% PEG and 18 times for MMMs with 10% MWCNT [35]. Composite membranes using non-stoichiometric ZIF-62 MOF glass and cellulose acetate (CA) are reported by Mubashir et al. The materials exhibited pore size (7.3 Å) and significant CO2 adsorption on the unsaturated metal nodes [36]. In more recent studies, another class of mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) are reported by Rehman et al. by incorporating (1–5 wt%) Cu-MOF-GO composites as filler into cellulose acetate (CA) polymer matrix by adopting the solution casting method. They reported 1.79 mmol g−1 and 7.98 wt% of CO2 uptake at 15 bar [37]. Some other foam-like cellulose composites reported by Wang et al with microporous metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) in a mesoporous cellulose template shows high durability during the temperature swing cyclic CO2 adsorption/desorption process and a high CO2 adsorption capacity of 1.46 mmol g−1 at 25 °C and atmospheric pressure [38].

3.2. Chitosan

Natural biopolymer chitosan (CS) is a marine waste material which is inexpensive, abundantly available, renewable, environmentally friendly and biodegradable polysaccharide and is the second most abundant natural polysaccharide after cellulose [39]. CS may be used in CO2 adsorption because of its ease of processability, low maintenance and energy necessity. CS chains have a large number of basic amine groups which facilitate adsorption of the acidic CO2 molecule on the surface of the adsorbents [40,41]. However, pure chitosan suffers from low surface area resulting lower carbon dioxide adsorption. Henceforth, most of the studies reporting chitosan-derived sorbents aim to fabricate the surface properties of CS and maximize the CO2 adsorption capacity [42]. Hierarchical porous nitrogen-containing activated carbons (N-ACs) were prepared with LiCl-ZnCl2 molten salt as a template derived from cheap chitosan via simple one-step carbonization under Ar atmosphere. The obtained N-ACs with the highest specific surface area of 2025 m2 g−1 and a high nitrogen content of 5.1 wt% were obtained using a low molten salt/chitosan mass ratio (3/1) and moderate calcination temperature (1000 °C). Importantly, using these N-ACs as CO2 solid-state adsorbents, the maximum CO2 capture capacities could be up to 7.9/5.6 mmol g−1 at 0 °C/25 °C under 1 bar pressure, respectively by physisorption mechanism. These CO2 capture capacities of N-ACs were the highest compared to reported biomass-derived carbon materials, and these values were also comparable to most of porous carbon materials. The N-ACs also showed good selectivity for CO2/N2 separation and excellent recyclability [43]. Chagas et al. reported a green method for CO2 capture by showing the effects of hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) on chitosan’s chemical properties and its potential. Chitosan’s surfaces and structural properties are modified after HTC which increases the CO2 adsorption capacity by 4-fold compared to the non-HTC treated chitosan [44]. Acetic acid-mediated chitosan-based porous carbons were developed by Kamaran et al. following a combination of hydrothermal carbonization treatment and chemical activation with KOH and NaOH under a flowing stream of nitrogen. The CO2 uptake was reported to be 8.36 mmol g−1 for KOH samples and 7.38 mmol g−1 for the NaOH sample. These synthesized carbon adsorbents also exhibited regenerability after four consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles and also high CO2 selectivity over N2 gas [45].

Azharul Islam et al. have reported a non-carbonized chitosan–bleaching earth clay composite (Chi–BE) as an efficient adsorbent for CO2. They showed that temperature, adsorbent loading and CO2 concentration exerted significantly positive effects on CO2 adsorption by Chi–BE within the ranges and levels studied, whereas the interaction of adsorbent loading and CO2 concentration only affected CO2 adsorption. The optimum conditions were 38.13 °C, adsorbent loading of 0.72 g and CO2 concentration of 25%, which produced the adsorption capacity of 7.84 mmol g−1 using the desirability function and the composite can also be recycled [46]. Material type and composition, BET surface area (m2 g−1), pore size (nm)/total pore volume (cm3 g−1), mechanism of adsorption, CO2 capture capacity (mmol g−1) and special features of chitosan-based materials have been tabulated in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of material type and composition, BET surface area (m2 g−1), pore size (nm)/total pore volume (cm3 g−1), mechanism of adsorption, CO2 capture capacity (mmol g−1) and special features of chitosan-based materials.

|

Material Type and Composition |

BET Surface Area (m2 g−1) |

Pore Size (nm)/Total Pore Volume (cm3 g−1) |

CO2 Capture Capacity (mmol g−1) |

Special Features |

Ref |

|

N-doped Atcivated carbon from chitosan char by KOH activation |

907 |

0.39 |

1.86 |

High CO2/N2 selectivity and excellent recyclability |

[40] |

|

N-doped carbonized chitosan |

849 |

0.5–1.0 nm, 1.0–1.5 nm and 1.5–2.5 nm with maximum pore volume of 0.68 |

3.2 |

Can be used as an electrode material and adsorbent |

[41] |

|

Pyrolyzed chitosan– and chitosan-periodic mesoporous organosilica (PMO)– based porous materials |

376 |

~2 nm, 0.346 |

1.9 at 500 kPa |

Best selectivity for CO2/CH4 separation at 1.5% (m/v) of chitosan solution dried under supercritical CO2 |

[42] |

|

N containing activated carbons (N-ACs) with LiCl-ZnCl2 molten salt as a template derived from cheap chitosan by carbonization. |

2025 |

1.15 |

7.9 mmol g−1 at 0 °C/25 °C, 1 bar |

Selectivity for CO2/N2 separation, excellent recyclability |

[43] |

|

Hydrothermal carbonized (HTC) of chitosan |

2 |

- |

0.45 |

- |

[44] |

|

Acetic acid-mediated chitosan-based highly porous carbon adsorbents |

4168 |

1.386 |

8.36 |

CO2 selectivity over N2 |

[45] |

|

Chitosan-Bleaching earth |

71.26 |

0.19 |

7.65 |

Recyclable |

[46] |

3.3. Lignin

Lignin is a class of complex organic polymers found in plants particularly important in the formation of cell walls, especially in wood and bark. Chemically, lignins are polymers made by cross-linking phenolic precursors. The synthesis of multiscale carbonized carbon supraparticles (SPs) by soft-templating lignin nano- and microbeads bound with cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs) have been reported by Zhao et al. which were well suited for CO2 capture (1.75 mmol g−1), while displaying a relatively low pressure drop (~33 kPa·m−1 calculated for a packed fixed-bed column). Moreover, the carbon SPs did not require doping with heteroatoms for effective CO2 uptake and also showed regeneration after multiple adsorption/desorption cycles [47]. Non-carbonized lignin-based materials have been reported by Shao et al. and Liu et al. [48,49]. Lignin depolymerization was done selecting six aromatic units from lignin and O-rich hyper-cross-linked polymers (HCPs) was developed by one-pot Friedel–Crafts alkylation reaction for CO2 capture. In a recent report, the resins were synthesized from lignin, 4-vinylbenzyl chloride, and divinylbenzene by free radical polymerization reaction followed by Friedel–Crafts reaction which displayed excellent CO2 capture (1.96 mmol g−1) at 273 K and 1 bar and reusability [49].

3.4. Cyclodextrins

Cyclodextrins are glucopyranosides bound together in various ring sizes renowned for their structural, physical and chemical properties. Due to their unique ability to encapsulate other molecules, they are widely used in industrial applications [50]. The cyclodextrin (CD)/graphene composite aerogel synthesized by hydrothermal carbonized reaction at 80 °C for 18 h exhibits an adsorption capacity of CO2 at 1.02 mmol g−1 [51]. Cyclodextrin-based non-carbonized materials also reported to be efficient CO2 adsorbent [52–54]. Two isostructural cyclodextrin-based CD-MOFs (CD-MOF-1 and CD-MOF-2) are demonstrated to have an inverse ability to selectively capture CO2 from C2H2 by single-component adsorption isotherms and dynamic breakthrough experiments. These two MOFs exhibit excellent adsorption capacity and selectivity (118.7) for CO2/C2H2 mixture at room temperature [52]. A new solid acid adsorbent for CO2 capture derived from β-cyclodextrin has been obtained which shows a capacity of 39.87 cm3/g at 3.5 bar [53]. For thermal activation, a rapid temperature-assisted synthesis has been reported to improve the porous structure of the cyclodextrins for CO2 adsorption [54]. Another category of cyclodextrin-based materials involves CO2 adsorption by thermal activation under N2 atmosphere [55,56].

- Synthetic Porous Organic Polymers (POPs) for CO2 Capture

A excellent choice of material for post-combustion carbon dioxide capture is synthetic porous organic polymers because of its low density, high porosity, large surface area, and high stability. Organic polymers are synthesized using a variety of chemical processes, including Friedel-Crafts, Schiff-base, Sonogashira-Hagihara, Buchwald-Hartwig amination, and Suzuki-Miyaura coupling. The polymers' intended pore size is achieved by choosing the monomer building blocks and linkers. The polymers' affinity for CO2 can also be increased by post-synthetic modification. There have been reports of several varieties of porous organic polymers in the literature [57]. Here is a summary of the four major types of POPs mentioned in Figure 1 and their CO2 capture capacity as reported in the last five years. Table 3 displays measured CO2 capture capacities, CO2/N2 selectivities, and other CO2 capture-related parameters for the POPs described in this report.

4.1. Hyper-Crosslinked Polymers (HCPs)

To prepare HCPs from monomers, Friedel-Crafts and straightforward condensation processes are typically used. Permanent porosity is produced in the HCPs by extensive cross-linking between the monomers. Despite the modest surface area of the majority of these kinds of polymers, HCPs generally showed significant CO2 capture capability. Hu et al. synthesized a microporous polymer, termed as PIM-1, by one-step condensation of 5,5′,6,6′-tetrahydroxy-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethyl-1,1′-spirobisindane and 2,3,5,6-tetrafluoroterephthalonitrile. The hydrolyzed form (hPIM-1) was prepared by hydrolysis of PIM-1 using NaOH. Hydrophilic hPIM-1 exhibited slightly higher CO2 uptake capacity than that of PIM-1. Both polymers are efficient in absorbing CO2 even at low partial pressures as 0.15 bar. PIM-1 demonstrated good competitive CO2 over N2 adsorption at a high total pressure of 1 bar and some degree of moisture resistance. PIM-1 can be solution-reprocessed while maintaining its ability to absorb CO2 [58]. Fayemiwo et al. synthesized a series of nitrogen-rich HCPs, poly[methacrylamide-co-(ethylene glycol dimethacrylate)] by copolymerisation of methacrylamide (MAAM) and ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) in different molar ratio via radical initiated bulk polymerizations. By increasing the amounts of MAAM relative to EGDMA by 1:2:3, respectively, three polymers, termed as HCP-MAAM-1, -2, and -3 were produced. Due to the presence of polar amide groups within the polymer network, these polymers demonstrated significant affinity towards CO2 at both high and low pressure [59]. By one-pot Friedel-Crafts alkylation of benzyl alcohol (BA) with formaldehyde dimethyl acetal (FDA) as an external cross-linker and anhydrous FeCl3, Liu et al. synthesized a number of hydroxyl-based HCPs. Pore volumes of the produced HCPs were discovered to be very sensitive to reaction time, FeCl3 and FDA concentrations. The HCPs obtained using optimum quantities of FeCl3 and FDA in the reactions possess high BET-specific surface areas up to 1101 m2/g and exhibit high CO2 uptake capacities up to 3.03 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar [60]. Abdelnaby et al. synthesized an HCP, termed KFUPM-1, by acid-catalyzed condensation of pyrrole, 1,4-benzenediamine and p-formaldehyde. The presence of a high concentration of amine groups in the backbone of this meso-/macroporous polymer resulted in high selectivity for CO2 over N2 and moderate CO2 uptake capacity [61]. In a similar manner, another HCP, termed KFUPM-2, was synthesized by Friedel−Crafts alkylation polymerization of phenothiazine and pyrrole (1:3 ratio) using p-formaldehyde as a cross-linker in the presence of FeCl3 as a catalyst. This microporous polymer showed a moderate CO2 uptake capacity and moderate CO2/N2 selectivity [62]. A novel ynone-linked porous organic polymer, named y-POP, was synthesized by Kong et al. by Sonogashira coupling of 1,3,5-triethynylbenzene with terephthaloyl chloride. Post-modification of y-POP by tethering alkyl amine species produced y-POP-NH2. Increase in amine loading, the CO2 adsorption capacity of y-POP-NH2 gradually increased up to 1.95 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar from the corresponding value of 1.34 mmol g−1 of y-POP under the same conditions [63]. Cross-linking of a copolymer polydivinylbenzenechloride (PDV) was performed by reaction with anhydrous FeCl3 and CCl4 to produce methylene cross-linked HCP, named PDV-pc-1. Another carbonyl cross-linked HCP, named PDV-pc-2 was obtained in a similar reaction without using CCl4. Studies showed that PDV-pc-1 has a higher BET-specific surface area than PDV-pc-2. However, the CO2 uptake capacity of PDV-pc-2 was found to be higher than PDV-pc-1. Higher porosity and the presence of a large number of carbonyl functional groups made PDV-pc-2 a better CO2-capturing agent [64]. Sharma et al. synthesized a heptazine-based microporous polymeric network, termed HMP-TAPA, by nucleophilic substitution of trichloroheptazine (TCH) by tris-(4-aminopenyl) amine (TAPA). The presence of a large number of CO2-philic -N-, -NH, and -NH2 groups on the surface enhanced CO2 sorption capacity of HMP-TAPA, which exhibited a CO2 uptake capacity of 2.42 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar [65]. A series of N-containing HCPs was synthesized from triphenylamine (TPA) and/or carbazole (Cz) monomers by one-step cross-coupling reactions including Scholl coupling and solvent knitting Friedel–Crafts reactions. Among these microporous polymers, HCP1, HCP2, and HCP3, prepared by Scholl coupling exhibited high CO2 uptake capacities (2.38–2.64 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar) due to high porosity though measured surface areas were found to be low. On the other hand, HCP4, HCP5, and HCP6, prepared by 1,2-dichloroethane knitting Friedel–Crafts reactions were found to be meso/macroporous in nature and they exhibited comparatively low CO2 uptake capacities (0.9–1.52 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar) due to their low porosity [66]. Mohamed et al. synthesized two microporous HCPs, named TPE-CPOP1 and TPE-CPOP2, by AlCl3 catalysed Friedel–Crafts reactions of tetraphenylethene (TPE) monomer with and without cyanuric chloride, respectively. CO2 adsorption capacities for both polymers were found to be moderate. The carbonization and KOH activation process of these HCPs produced porous carbon materials which exhibited high CO2 uptake capacities [67]. Qiao et al. prepared two HCPs, named P0 and P1, by one-step reaction of each p-terphenyl and 4-amino-p-terphenyl monomers with AlCl3 catalyst in dichlorometane, respectively. Further reaction of nitrobenzene and P1 in 1:3 ratios afforded another HCP, named P2. CO2 uptake capacities of P0, P1 and P2 were found to be 3.79, 4.24, and 3.02 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1.13 bar. The remarkable CO2 uptake capacity of P1 was attributed due to the presence of the amine groups in the polymeric network [68]. Zhou et al. synthesized a series of microporous HCPs by Friedel−Crafts polymerization of each hexaphenylbenzene (HPB), triphenylbenzene (TPB), spirobisfluorene (SBF), and triptycene (Trip) monomers catalyzed by AlCl3 in the presence of dichloromethane, which acts as both the solvent and as a cross-linker. The polymers were functionalized further by covalently attaching −NO2, −NH2, and −SO3H groups. Generally, surface functionalization of the polymers causes loss of porosity but nitro- and sulfonic acid-containing polymers retained a good amount of initial porosity. Sulfonated polymers showed high BET surface areas in the range of 1145 to 1390 m2/g and highest CO2 uptake capacity reached to 6.77 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar [69]. Abdelnaby et al. synthesized two azo-linked porous organic polymers, termed man-Azo-P1 and man-Azo-P2, by diazotization reactions of 4,4′-diaminobiphenyl (benzidine) and 4,4′-diaminodianiline, respectively, with phloroglucinol in aqueous medium at 0 °C. The CO2 uptake capacities for both polymers were found to be moderate and the former exhibited better CO2 uptake capacity due to the presence of polar azo and hydroxy functional groups in the framework [70].

Table 3. Summary of synthetic process, surface area, pore size, total pore volume, CO2 uptake capacity, CO2/N2 selectivity and heat of adsorption of the synthetic POPs.

|

POPs |

Synthetic Process |

SBETa

|

Pore Sizeb |

Vtotc |

CO2 Capture Capacityd

|

CO2/N2 Selectivitye |

Qstf |

Ref. |

||

|

273 K |

298 K |

273 K |

298 K |

|

|

|||||

|

PIM-1 |

One-step condensation in presence of K2CO3 |

970 |

<2, 2–50 |

0.70 |

- |

1.66 |

- |

19.3 |

20.8 |

[58] |

|

hPIM-1 |

Hydrolyzation of PIM-1 using NaOH |

780 |

<2, 2–50 |

0.49 |

- |

1.73 |

- |

11.7 |

32.8 |

[58] |

|

HCP-MAAM-1 |

Radical initiated bulk copolymerization |

298 |

2–40 |

0.47 |

1.56 |

0.92 |

45–86 |

38–48 |

28–35 |

[59] |

|

HCP-MAAM-2 |

Radical initiated bulk copolymerization |

142 |

2–40 |

0.87 |

1.45 |

0.85 |

50–99 |

38–63 |

28–35 |

[59] |

|

HCP-MAAM-3 |

Radical initiated bulk copolymerization |

83 |

2–40 |

0.24 |

1.28 |

0.79 |

52–104 |

45–72 |

28–35 |

[59] |

|

BAHCP-7 |

Friedel-Crafts alkylation polymerization

|

1101 |

1.7 |

1.15 |

3.03 |

1.96 |

35 |

- |

26–28 |

[60] |

|

KFUPM-1 |

Acid catalyzed polycondensation |

305 |

- |

- |

1.52 |

1.04 |

- |

141 |

34 |

[61] |

|

KFUPM-2 |

Friedel−Crafts alkylation polymerization |

352 |

- |

0.21 |

1.75 |

1.04 |

- |

51 |

34 |

[62] |

|

y-POP |

Sonogashira coupling |

226 |

0.74, 1.2, 34 |

- |

1.34 |

- |

20 |

- |

29 |

[63] |

|

y-POP-A1 |

Amine modification of y-POP |

145 |

- |

- |

1.50 |

- |

239 |

- |

46.8 |

[63] |

|

PDV |

Radical polymerzation |

364 |

1–2 |

0.20 |

0.66 |

0.25 |

31.3 |

- |

36.9 |

[64] |

|

PDV-pc-1 |

Friedel−Crafts reaction of PDV |

686 |

1–2 |

0.37 |

1.45 |

0.59 |

16.4 |

- |

34.3 |

[64] |

|

PDV-pc-2 |

Friedel−Crafts reaction of PDV |

635 |

1–2 |

0.33 |

1.95 |

0.80 |

46.8 |

- |

39.7 |

[64] |

|

HMP-TAPA |

Polymerization via nucleophilic substitution reaction |

424 |

0.7–1.2, 2–4 |

- |

2.42 |

- |

26.27 |

30.79 |

32.8 |

[65] |

|

HCP1 |

Scholl coupling |

534.5 |

- |

0.32 |

2.64 |

1.57 |

23.6 |

- |

46.7 |

[66] |

|

HCP2 |

Scholl coupling |

215.7 |

- |

0.11 |

2.38 |

1.51 |

30.2 |

- |

28.0 |

[66] |

|

HCP3 |

Scholl coupling |

199.9 |

- |

0.12 |

2.47 |

1.46 |

26.7 |

- |

36.7 |

[66] |

|

HCP4 |

Friedel−Crafts alkylation polymerization |

10.8 |

- |

0.023 |

1.05 |

0.72 |

8.6 |

- |

26.2 |

[66] |

|

HCP5 |

Friedel−Crafts alkylation polymerization |

34.8 |

- |

0.065 |

1.52 |

0.72 |

15.4 |

- |

39.8 |

[66] |

|

HCP6 |

Friedel−Crafts alkylation polymerization |

30.3 |

- |

0.061 |

0.90 |

0.42 |

7.0 |

- |

33.0 |

[66] |

|

TPE-CPOP1 |

Friedel-Crafts polymerization |

489 |

1.49, 1.82 |

0.269 |

0.99 |

0.89 |

- |

- |

- |

[67] |

|

TPE-CPOP2 |

Friedel-Crafts polymerization |

146 |

2.57 |

0.1 |

1.26 |

1.15 |

- |

- |

- |

[67] |

|

TPE-CPOP1-800 |

Carbonization and KOH activation of TPE-CPOP1 |

1177 |

1.04, 2.99 |

0.48 |

3.19 |

1.74 |

- |

- |

- |

[67] |

|

TPE-CPOP2-800 |

Carbonization and KOH activation of TPE-CPOP2 |

1165 |

1.02, 2.29 |

0.62 |

2.93 |

1.72 |

- |

- |

- |

[67] |

|

P0 |

Friedel-Crafts polymerization |

1062 |

5.65 |

0.69 |

3.79 |

- |

- |

18.28 |

24–32 |

[68] |

|

P1 |

Friedel-Crafts polymerization |

447 |

1.91 |

0.21 |

4.24 |

- |

- |

20.97 |

24–32 |

[68] |

|

P2 |

Condensation polymerization using base |

242 |

1.94 |

0.12 |

3.02 |

- |

- |

34.52 |

24–32 |

[68] |

|

PIM-TPB |

Friedel−Crafts polymerization |

2540 |

0.35, 0.56, 0.86 |

1.300 |

5.00 |

2.57 |

- |

14.1 |

25.2 |

[69] |

|

PIM-TPB-NO2 |

-NO2 functionalization of PIM-TPB using HNO3 |

950 |

0.35, 0.56, 0.86 |

0.553 |

5.13 |

3.11 |

- |

24.7 |

32.1 |

[69] |

|

PIM-TPB-NH2 |

-NH2 functionalization by Na2S2O4 treatment of PIM-TPB-NO2 |

710 |

0.35, 0.56, 0.86 |

0.333 |

4.45 |

2.98 |

- |

26.1 |

31.7 |

[69] |

|

PIM-TPB-HSO3 |

-SO3H functionalization of PIM-TPB using H2SO4 |

1585 |

0.35, 0.56, 0.86 |

0.852 |

6.77 |

4.07 |

- |

17.9 |

29.0 |

[69] |

|

man-Azo-P1 |

Diazotization of aromatic diamines followed by coupling with aromatic alcohol |

290 |

- |

0.33 |

1.43 |

- |

80 |

- |

40 |

[70] |

|

man-Azo-P2 |

Diazotization of aromatic diamines followed by coupling with aromatic alcohol |

78 |

- |

0.15 |

0.89 |

- |

110 |

- |

23 |

[70] |

|

TPE-COF-I |

Acid catalysed condensation |

1535 |

- |

1.65 |

3.06 |

1.69 |

- |

- |

- |

[71] |

|

TPE-COF-II |

Acid catalysed condensation |

2168 |

- |

2.14 |

5.30 |

2.70 |

- |

- |

- |

[71] |

|

Co(II)@TA-TF COF |

Solvothermal reaction |

1076 |

1.6 |

- |

- |

3.84 |

- |

- |

- |

[72] |

|

COF-609-Im |

Acid catalysed condensation |

724 |

- |

- |

1.5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

[73] |

|

COF-609 |

aza-Diels−Alder cycloaddition of COF-609-Im followed by amination |

- |

- |

- |

0.076 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

[73] |

|

CMP-LS1 |

Suzuki coupling |

493 |

0.4–1.4 |

0.32 |

1.38 |

0.76 |

23.2 |

- |

30.2 |

[75] |

|

CMP-LS2 |

Suzuki coupling |

1576 |

0.4–1.4 |

1.06 |

3.88 |

2.1 |

27.9 |

- |

31.6 |

[75] |

|

CMP-LS3 |

Sonogashira-Hagihara coupling |

643 |

0.4–1.4 |

0.37 |

1.88 |

1.07 |

19.8 |

- |

30.4 |

[75] |

|

LKK-CMP-1 |

Oxidative homocoupling |

467 |

0.59 |

0.371 |

2.22 |

1.38 |

- |

44.2 |

35 |

[76] |

|

Azo-Cz-CMP |

One-pot reductive reaction using NABH4 |

315 |

0.79 |

- |

2.13 |

0.91 |

- |

- |

32.08 |

[77] |

|

Azo-Tz-CMP |

One-pot reductive reaction using NABH4 |

225 |

1.18 |

- |

1.36 |

0.64 |

- |

- |

18.36 |

[77] |

|

TrzPOP-1 |

Polycondensation |

995 |

1.7 |

- |

6.19 |

3.53 |

108.4 |

42.1 |

29 |

[78] |

|

TrzPOP-2 |

Polycondensation |

868 |

1.5 |

- |

7.51 |

4.52 |

140.6 |

75.7 |

34 |

[78] |

|

TrzPOP-3 |

Polycondensation |

772 |

1.4 |

- |

8.54 |

5.09 |

167.4 |

94.5 |

37 |

[78] |

|

NT-POP-5 |

Suzuki cross-coupling |

8 |

- |

- |

0.78 |

- |

- |

- |

25.4–19.4 |

[79] |

|

NT-POP@800-4 |

Pyrolysis of NT-POP-1-6 at 800 oC |

736 |

- |

0.463 |

3.96 |

3.25 |

36.9 |

- |

25.4–19.4 |

[79] |

|

CTF1 |

ZnCl2 catalyzed ionothermal reaction |

1654 |

- |

1.06 |

5.23 |

3.32 |

- |

11 |

34.0 |

[80] |

|

CTF4 |

ZnCl2 catalyzed ionothermal reaction |

784 |

- |

0.41 |

4.39 |

3.83 |

- |

46 |

21.5 |

[80] |

|

CTF-DCE |

ZnCl2 catalyzed ionothermal reaction |

1355 |

0.6, 1.2, 2–4 |

0.93 |

4.34 |

3.59 |

54 |

- |

24.9 |

[81] |

|

CTF-PF-4 |

ZnCl2 catalyzed ionothermal reaction |

889 |

1.7–1.9 |

0.58 |

2.0 |

1.27 |

- |

- |

>33 |

[82] |

|

ICTF-Cl |

ZnCl2 catalyzed ionothermal reaction |

751 |

- |

0.458 (approx.) |

2.36 |

1.41 |

119.1 |

68.74 |

- |

[83] |

|

ICTF-SCN |

ZnCl2 catalyzed ionothermal reaction |

1000 (approx.) |

- |

0.458 (approx.) |

2.48 |

1.40 |

39.28 |

24.82 |

- |

[83] |

|

CTF-N4 |

ZnCl2-mediated cyclotrimerization |

701 |

- |

0.31 |

3.4 |

2.2 |

45 |

- |

44 |

[84] |

|

CTF-N6 |

ZnCl2-mediated cyclotrimerization at high temperature |

1236 |

- |

0.51 |

5.0 |

3.4 |

36 |

- |

26 |

[84] |

|

CTF-hex4 |

ZnCl2-mediated ionothermal reaction |

609 |

- |

0.31 |

3.4 |

- |

- |

- |

29 |

[85] |

|

CTF-hex6 |

ZnCl2-mediated ionothermal reaction |

1728 |

- |

0.87 |

3.1 |

- |

- |

- |

37 |

[85] |

|

An-CTF-20-500 |

ZnCl2-mediated ionothermal reaction |

700 |

1.06, 1.66 |

- |

5.25 |

2.69 |

- |

- |

- |

[86] |

aBET surface area (m2 g−1). bPore size (nm). cTotal pore volume (cm3 g−1). dCO2 capture capacity (mmol g−1) at 1 bar. eIAST (ideal adsorbed solution theory) for the mixture including 85% of N2 and 15% of CO2 at 1 bar. fHeat of absorption ( kJ mol−1) of CO2 (calculated using Clausius-Clapeyron equation at low CO2 loading).

4.2. Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs)

The monomer building blocks and reaction conditions allow for precise control of the structure and pore size of COFs. Gao et al. synthesized two 2D-COFs by condensation of amine and aldehyde functionalized tetraphenylethane (TPE). Solvent controlled [4 + 4] condensation produced TPE-COF-I and an unusual [2 + 4] condensation pathway produced TPE-COF-II. TPE-COF-II exhibited higher CO2 capture capacity (5.3 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 atm) than TPE-COF-I (3.06 mmol g−1) due to the presence of unreacted —CHO groups in the framework [71]. Li et al. designed and synthesized a metalloporphyrin-containing COF by solvothermal reaction of cobalt(II)-5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-aminophenyl)porphyrin (Co(II)@TAPP) and tetrakis(4-formylphenyl)pyrene (TFPPy). The COF captures CO2 and catalytically converts it into cyclic carbonates under mild conditions. High surface area, good stability and the presence of a single type of micropores made it a good catalyst. The COF exhibited a strong CO2 adsorption capacity of 3.84 mmol g−1 at 298 K and 1 bar. Co(II)@TAPP units in the COF are alternately stacked perpendicular to the porphyrin planes with a slipped distance of 1.7 Å which fits with the size of CO2. Adsorbed CO2 molecules interact effectively with the metal centres (catalytic sites) and facilitate catalytic reactions [72]. Lyu et al. established a new synthetic strategy to covalently attach aliphatic amines to construct COFs. First, an imine-linked COF, named COF-609-Im, was synthesized through imine condensation between 2,4,6-tris(4-formylphenyl)-1,3,5-triazine (TFPT) and 4,4′-diaminobenzanilide (DABA). Crystallization of COF-609-Im, followed by conversion of its imine linkage to base-stable tetrahydroquinoline (THQ) linkage through aza-Diels−Alder cycloaddition produced COF-609-THQ-Im. Finally, the covalent incorporation of tris(3-aminopropyl)amine (TRPN) into the framework produced COF-609. CO2 capture capacity of COF-609 was found to be 1360 times higher compared to that of COF-609-THQ-Im at 0.4 mbar CO2 and 273 K. Further 29% increase in CO2 capture was observed in the presence of humidity. This condition is comparable to direct air capture of CO2. Strong chemisorptions of CO2 by aliphatic amines incorporated into COFs made these sorbents such efficient capturing agents at low CO2 pressures. These three COFs also exhibited excellent CO2 capture capacities at 40 mbar (comparable to post-combustion capture from natural gas burned flue gas) and 150 mbar (comparable to post-combustion capture from coal-fired flue gas) pressures of CO2 [73].

4.3. Conjugated Microporous Polymers (CMPs)

CMPs are typically made by coupling or cross-coupling aromatic monomers using a variety of well-known reactions, including the Suzuki, Sonogashira, and Yamamoto cross-coupling reactions. The polymers' pore size, surface areas, and CO2-philic nature can be tailored by carefully choosing the monomers, reactions, and post-synthetic modifications [74]. Wang et al. synthesized three novel biphenylene-based CMPs, termed CMP-LS1, CMP-LS2 and CMP-LS3, by palladium-catalyzed Suzuki and Sonogashira–Hagihara cross-coupling reactions of 3,4′,5-tribromobiphenyl (TBBP) with each 1,4-phenylenediboronic acid, 1,3,5-tris(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)benzene and 1,3,5-triethynylbenzene, respectively. Among the three CMPs, CMP-LS2 exhibited highest CO2 adsorption capacity of 3.88 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar due to its large surface area [75]. By oxidative homocoupling of 1,3,6,8-tetraethynylpyrene monomer using Pd(II)-Cu(I) catalysts Ren et al. prepared a CMP, named LKK-CMP-1. This 1,3-diyne linked CMP exhibited moderate CO2 uptake capacity [76]. Saber et al. synthesized two azo-linked CMPs, termed Azo-Cz-CMP and Azo-Tz-CMP, by reduction of the corresponding monomers 3,6-dinitro-9-(4-nitrophenyl) carbazole (Cz-3NO2) and 3,7-dinitro-10-(4-nitrophenyl)-10H-phenothiazine (Tz-3NO2), respectively, using sodium borohydride (NaBH4). The former exhibited higher CO2 capture capacity than the later [77].

4.4. Covalent Triazine-Based Frameworks (CTFs)

The aromatic triazine (C3N3) rings' high nitrogen concentration in CTFs improves their affinity for CO2. Additionally, high stability and abundant micropores in the surface made CTFs potential CO2 capturing agents [5]. Das et al. synthesized three CTFs, namely TrzPOP-1, -2 and -3, via polycondensation of two tetraamine bearing triazine ring and three different dialdehydes (two of them contain phenolic –OH groups). TrzPOP-1, -2 and -3 possess high BET surface areas and they exhibited high CO2 uptake capacities of 6.19, 7.51 and 8.54 mmol g−1, respectively, at 273 K and 1 bar. Though BET surface areas of TrzPOP-2 and TrzPOP-3 are comparatively low still they exhibited high CO2 uptakes because of the presence of phenolic –OH groups [78]. Yao et al. synthesized a series of six CTFs, termed NTPOP-1 to -6, by Suzuki cross-coupling driven polycondensation of N2, N4, N6-tris(4-bromophenyl)-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triamine (TPTT) and a number of benzeneboronic monomers or ethynyl monomers. BET surface areas of the NTPOPs were found to be in the lower side and they exhibited moderate CO2 uptake capacities. Carbonization of these NTPOPs at 800 °C produced pore-tunable porous carbon materials which exhibited excellent CO2 adsorption capacities of 2.83–3.96 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1.05 bar [79]. A set of five CTFs (CTF1–5) were prepared by ionothermal reactions of dicyano-aryl or heteroaryl monomer and molten ZnCl2 in 1:5 molar ratio at temperature 400 °C (first 10 h) and 600 °C (next 10 h). Obtained CTFs were found to be bimodal micro-mesoporous in nature and they displayed high specific surface areas (up to 1860 m2/g). Selected polymers of this series displayed excellent CO2 uptake capacities and highest uptake value was found to be 5.23 and 3.83 mmol g−1 at 273 and 298 K, respectively, at ambient pressure [80]. In a similar way, Dang et al. synthesized a CTF, termed CTF-DCE, via ZnCl2 catalyzed ionothermal trimerization of di(4-cyanophenyl)ethyne. CTF-DCE displayed high BET surface area of 1355 m2/g and excellent CO2 capture capacity of 4.34 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar [81]. Utilizing the similar strategy, a series of four CTFs based on imidazolium salts were synthesized by Xu et al. via ionothermal reactions of nitriles and ZnCl2 in different ratios at 400 °C. The obtained CTFs, were termed as CTF-Cl-1, CTF-Cl-2, CTF-PF-3, and CTF-PF-4 based on the type and number of counterions (Cl− and PF6−) present. These CTFs displayed high BET surface areas. Pore volumes and sizes of the CTFs can be controlled by simply exchange of counterions. CTF-PF-4 containing highest PF6− content, showed highest CO2 adsorption of 2.0 mmol g−1 [82]. Zhu et al. reported synthesis of a series of bipyridinium-based ionic covalent triazine frameworks (ICTFs) with anions Cl− and SCN− through ZnCl2 catalyzed ionothermal polymerization. High specific surface area, microporous structure, ionic nature and high nitrogen content made them excellent CO2 capturing agents. The surface area and porosity can be regulated by adjusting the anions. Both ICTF-SCN and ICTF-Cl showed high CO2 uptake capacities of 2.48 and 2.36 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar, respectively [83]. Three PhNH-, PhO-, and PhS-linked CTFs were synthesized by Liao et al. via ZnCl2 mediated cyclotrimerization of nitrile-containing monomers including 2,4,6-tris(4-cyanophenylamino)-1,3,5-triazine (TAT), 2,4,6-tris(4-cyanophenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine (TOT), and 2,4,6-tris(4-cyanobenzenesulfenyl)-1,3,5-triazine (TST) by stepwise heating method. These microporous CTFs possess high BET surface areas and found to be excellent CO2 sorbents. The PhNH-linked CTF prepared at high temperature (600 °C) displayed very high CO2 adsorption capacity (5.0 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar). The CO2 capture performances of the three CTFs were found to be in the order of PhNH- > PhO- > PhS-linked CTF [84]. Wessely et al. reported synthesis of a series of CTFs using pseudo-octahedral hexanitrile 1,4-bis(tris(4′-cyanophenyl) methyl) benzene (BTB-nitrile) monomer. Among these, CTF-hex6 was prepared under ionothermal reaction conditions with ZnCl2 at 400 °C and CTF-hex1 was prepared under mild reaction conditions with the strong Brønsted acid trifluoromethanesulfonic acid at room temperature. In addition, the BTB-nitrile was combined with different di-, tri-, and tetranitriles as a second linker under ionothermal reactions under the same conditions produced mixed-linker CTFs, named CTF-hex2-6. These CTFs displayed BET surface areas in a wide range of 493 m2/g to 1728 m2/g. They exhibited CO2 capture capacities in the range 2.5 to 3.4 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar [85]. A series of porous covalent triazine framework (An-CTFs) based on 9,10 dicyanoanthracene (An-CN) units was prepared by Mohamed et al. via ionothermal reactions of AnCN and molten ZnCl2 in two different molar ratios (1:10 and 1:20) at two different temperatures (400 °C and 500 °C). These microporous highly stable An-CTFs exhibited high CO2 adsorption capacity up to 5.65 mmol g−1 at 273 K and 1 bar [86].

- Conclusions

In this review, we have provided an overview of the synthesis, CO2 capture potential, and key factors influencing the CO2-philicity of several natural and synthetic POPs that have been described in the literature over the last five years. Despite the relatively low CO2 capture capabilities of biopolymers, microporous and nanoporous materials made from them showed good adsorption capability. Particularly, membranes made of nanocellulose were discovered to be prospective candidates for the large-scale capture and separation of CO2 from flue gas. The average CO2 uptake capacity and selectivity of synthetic POPs, such as HCPs, COFs, CMPs, and CTFs, is greater than that of porous carbonaceous materials. In the study for creating novel materials for post-combustion CO2 capture and separation, POPs played a significant role. POPs with large surface area (>1000 m2/g), micropores, and the presence of CO2-philic functional groups (such as -NH2, -OH, etc.) on the surface have all been shown to be viable CO2 capture candidates. Large-scale CO2 capture requires solid adsorbents that have strong moisture resistance, >2 mmol g−1 CO2 adsorption capacity, and >100 CO2/N2 selectivity. At the same time, the adsorbent's mass manufacture must be economical.

Using POPs to capture CO2 has made significant progress thus far, but there are still many obstacles to overcome. Surface modification and processability are hampered by many biopolymers' low solubilities in common solvents. As a result, creation of POPs membranes, which are very helpful for large-scale CO2 capture and separation, becomes problematic. Concerns remain about their large-scale usage stem from the fact that many POPs were produced utilizing pricey monomers and metal catalysts. Flue gas has a partial pressure of CO2 as low as 3-15 kPa and a temperature between 80 and 90 °C. Therefore, it is necessary to increase the CO2 capture capabilities of POPs at high temperatures and low pressures..

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, S.K.G. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.G. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, S.K.G. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

[1]

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/polysaccharides4020012

References

- References1. Raupach, M.R.; Marland, G.; Ciais, P.; Quẻrẻ, C.L.; Canadell, J.G.; Klepper, G.; Field, C.B. Global and Regional Drivers of Accelerating CO2 Emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 10288–10293.2. Goeppert, A.; Czaun, M.; Prakash, G.K.S.; Olah, G.A. Air as the Renewable Carbon Source of the Future: An Overview of CO2 Capture from the Atmosphere. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 7833–7853.3. Qaroush, A.K.; Alshamaly, H.S.; Alazzeh, S.S.; Abeskhron, R.H.; Assaf, K.I.; Eftaiha, A.F. Inedible Saccharides: A Platform for CO2 Capturing. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 1088–1100.4. Zeng, Y.; Zou, R.; Zhao, Y. Covalent Organic Frameworks for CO2 Capture. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 2855–2873.5. Wang, W.; Zhou, M.; Yuan, D. Carbon Dioxide Capture in Amorphous Porous Organic Polymers. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 1334–1347.6. Bhanja, P.; Modak, A.; Bhaumik, A. Porous Organic Polymers for CO2 Storage and Conversion Reactions. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 244–257.7. Ben-Mansour, R.; Habib, M.A.; Bamidele, O.E.; Basha, M.; Qasem, N.A.A.; Peedikakkal, A.; Laoui, T.; Ali, M. Carbon Capture by Physical Adsorption: Materials, Experimental Investigations and Numerical Modeling and Simulations: A Review. Appl. Energy 2016, 161, 225–255.8. Zou, L.; Sun, Y.; Che, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Bosch, M.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Smith, M.; Yuan, S.; et al. Porous Organic Polymers for Post-Combustion Carbon Capture. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1700229.9. Porta, R.; Sabbah, M.; Di Pierro. P. Biopolymers as Food Packaging Materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4942.10. Inostroza-Brito, K.E.; Collin, E.C.; Majkowska, A.; Elsharkawy, S.; Rice, A.; Hernández, A.E.R.; Xiao, X.; Rodríguez-Cabello, J.C.; Mata, A. Cross-Linking of a Biopolymer-Peptide Co-assembling System. Acta Biomater. 2017, 58, 80–89.11. Ma, J.; Sahai, Y. Chitosan Biopolymer for Fuel Cell Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 955–975.12. Ghosh, M.; Majkowska, A.; Mirsa, R.; Bera, S.; Rodríguez-Cabello, J.C.; Mata, A.; Adler-Abramovich, L. Disordered Protein Stabilization by Co-Assembly of Short Peptides Enables Formation of Robust Membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 464–473.13. Wu, J.; Shaidani, S.; Theodossiou, S.K.; Hartzell, E.J.; Kaplan, D.L. Localized, on-Demand, Sustained Drug Delivery from Biopolymer-Based Materials. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2022, 19, 1317–1335.14. Ghosh, M.; Halperin-Sternfeld, M.; Grinberg, I.; Adler-Abramovich, L. Injectable Alginate-Peptide Composite Hydrogel as a Scaffold for Bone Tissue Regeneration. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 497.15. Souza, M.A.D.; Vilas-Boas, I.T.; Leite-da-Silva, J.M.; Abrahão, P.D.N.; Teixeira-Costa, B.E.; Veiga-Junior, V.F. Polysaccharides in Agro-Industrial Biomass Residues. Polysaccharides 2022, 3, 95–120.16. Chowdhuri, S.; Ghosh, M.; Adler-Abramovich, L.; Das, D. The Effects of a Short Self-Assembling Peptide on the Physical and Biological Properties of Biopolymer Hydrogels. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1602.17. Salave, S.; Rana, D.; Sharma, A.; Bharathi, K.; Gupta, R.; Khode, S.; Benival, D.; Kommineni, N. Polysaccharide Based Im-plantable Drug Delivery: Development Strategies, Regulatory Requirements, and Future Perspectives. Polysaccharides 2022, 3, 625–654.18. Fernandes, M.; Souto, A.P.; Dourado, F.; Gama, M. Application of Bacterial Cellulose in the Textile and Shoe Industry: De-velopment of Biocomposites. Polysaccharides 2021, 2, 566–581.19. Marques, C.S.; Silva, R.R.A.; Arruda, T.R.; Ferreira, A.L.V.; Oliveira, T.V.; Moraes, A.R.F.; Dias, M.V.; Vanetti, M.C.D.; Soares, N.D.F.F. Development and Investigation of Zein and Cellulose Acetate Polymer Blends Incorporated with Garlic Essential Oil and β-Cyclodextrin for Potential Food Packaging Application. Polysaccharides 2022, 3, 277–291.20. Field, J.L.; Richard, T.L.; Smithwick, E.A.H.; Cai, H.; Laser, M.S.; LeBauer, D.S.; Long, S.P.; Paustian, K.; Qin, Z.; Sheehan, J.J.; et al. Robust Paths to Net Greenhouse Gas Mitigation and Negative Emissions Via Advanced Biofuels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 21968–21977.21. Xu, C.; Strømme, M. Sustainable Porous Carbon Materials Derived from Wood-Based Biopolymers for CO2 Capture. Nano-materials 2019, 9, 103.22. Heo, Y.J.; Park, S.J. A Role of Steam Activation on CO2 Capture and Separation of Narrow Microporous Carbons Produced from Cellulose Fibers. Energy 2015, 91, 142–150.23. Zhuo, H.; Hu, Y.; Tong, X.; Zhong, L.; Peng, X.; Sun, R. Sustainable Hierarchical Porous Carbon Aerogel from Cellulose for High-Performance Supercapacitor and CO2 Capture. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 87, 229–235.24. Sevilla, M.; Fuertes, A.B. Sustainable Porous Carbons with A Superior Performance for CO2 Capture. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 1765–1771.25. Xu, C.; Ruan, C.Q.; Li, Y.; Lindh, J.; Strømme, M. High-Performance Activated Carbons Synthesized from Nanocellulose for CO2 Capture and Extremely Selective Removal of Volatile Organic Compounds. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2018, 2, 1700147.26. Ho, N.A.D.; Leo, C.P. A Review on the Emerging Applications of Cellulose, Cellulose Derivatives and Nanocellulose in Carbon Capture. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111100.27. Kamran, U.; Park, S.J. Acetic Acid-Mediated Cellulose-Based Carbons: Influence of Activation Conditions on Textural Features and Carbon Dioxide Uptakes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 594, 745–758.28. Wang, C.; Okubayashi, S. Polyethyleneimine-Crosslinked Cellulose Aerogel for Combustion CO2 Capture. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 225, 115248.29. Sun, Y.; Chu, Y.; Wu, W.; Xiao, H. Nanocellulose-Based Lightweight Porous Materials: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 255, 117489.30. Sepahvand, S.; Bahmani, M.; Ashori, A.; Pirayesh, H.; Yu, Q.; Dafchahi, M.N. Preparation and Characterization of Air Nan-ofilters Based on Cellulose Nanofibers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 1392–1398.31. Chen, X.; Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Sun, Q.; Shen, X.; Li, Y. Epoxy-Functionalized Polyethyleneimine Modified Epichlorohydrin-Cross-Linked Cellulose Aerogel as Adsorbents for Carbon Dioxide Capture. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 302, 120389.32. Ansaloni, L.; Gay, J.S.; Ligi, S.; Baschetti, M.G. Nanocellulose-Based Membranes for CO2 Capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 522, 216–225.33. Venturi, D.; Grupkovic, D.; Sisti, L.; Baschetti, M.G. Effect of Humidity and Nanocellulose Content on Polyvinyla-mine-Nanocellulose Hybrid Membranes for CO2 Capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 548, 263–274.34. Venturi, D.; Chrysanthou, A.; Dhuiège, B.; Missoum, K.; Baschetti, M.G. Arginine/Nanocellulose Membranes for Carbon Capture Applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 877.35. Hussain, A.; Farrukh, S.; Hussain, A.; Ayoub, M. Carbon Capture from Natural Gas Using Multi-Walled CNTs Based Mixed Matrix Membranes. Environ. Technol. 2017, 40, 843–854.36. Mubashir, M.; Dumée, L.F.; Fong, Y.Y.; Jusoh, N.; Lukose, J.; Chai, W.S.; Show, P.L. Cellulose Acetate-Based Membranes by Interfacial Engineering and Integration Of ZIF-62 Glass Nanoparticles for CO2 Separation. J. Hazard Mater. 2021, 415, 125639.37. Rehman, A.; Jahan, Z.; Sher, F.; Noor, T.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Akram, M.A.; Sher, E.K. Cellulose Acetate Based Sustainable Nanostructured Membranes for Environmental Remediation. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135736.38. Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Q. Strong Foam-Like Composites from Highly Mesoporous Wood and Metal-Organic Frameworks for Efficient CO2 Capture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 29949–29959.39. Li, A.; Lin, R.; Lin, C.; He, B.; Zheng, T.; Lu, L.; Cao, Y. An Environment-Friendly and Multi-Functional Absorbent from Chitosan for Organic Pollutants and Heavy Metal Ion. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 148, 272–280.40. Li, D.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Tian, Y.; Lu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Li, J.; Wen, L. Improving Low-Pressure CO2 Capture Performance of N-Doped Active Carbons by Adjusting Flow Rate of Protective Gas During Alkali Activation. Carbon 2017, 114, 496−503.41. Wu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Gao, M.; Huang, L.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Xie, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yu. S. N-Doped Porous Carbon from Different Nitrogen Sources for High-Performance Supercapacitors and CO2 Adsorption. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 786, 826−838.42. Lourenço, M.A.O.; Nunes, C.; Gomes, J.R.B.; Pires, J.; Pinto, M.L.; Ferreira, P. Pyrolyzed Chitosan-Based Materials for CO2/CH4 Separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 362, 364−374.43. Wang, P.; Zhang, G.; Chen, W.; Chen, Q.; Jiao, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Deng, X. Molten Salt Template Synthesis of Hierarchical Porous Nitrogen-Containing Activated Carbon Derived from Chitosan for CO2 Capture. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 23460–23467.44. Chagas, J.A.O.; Crispim, G.O.; Pinto, B.P.; Gil, R.A.S.S.; Mota, C.J.A. Synthesis, Characterization, and CO2 Uptake of Adsor-bents Prepared by Hydrothermal Carbonization of Chitosan. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 29520–29529.45. Kamran, U.; Park, S.J. Tuning Ratios of KOH and NaOH on Acetic Acid-Mediated Chitosan-Based Porous Carbons for Im-proving Their Textural Features and CO2 Uptakes. J. CO₂ Util. 2020, 40, 101212.46. Islam, M.A.; Tan, Y.L.; Islam, M.A.; Romić, M.; Hameed, B.H. Chitosan–Bleaching Earth Clay Composite as An Efficient Adsorbent for Carbon Dioxide Adsorption: Process Optimization. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 554, 9–15.47. Zhao, B.; Borghei, M.; Zou, T.; Wang, L.; Johansson, L.S.; Majoinen, J.; Sipponen, M.H.; Österberg, M.; Mattos, B.D.; Rojas, O.J. Lignin-Based Porous Supraparticles for Carbon Capture. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 6774−6786.48. Shao, L.; Liu, N.; Wang, L.; Sang, Y.; Wan, H.; Zhan, P.; Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Chen, J. Facile Preparation of Oxygen-Rich Porous Polymer Microspheres from Lignin-Derived Phenols for Selective CO2 Adsorption and Iodine Vapor Capture. Chemo-sphere 2022, 288, 132499.49. Liu, N.; Shao, L.; Wang, C.; Sun, F.; Wu, Z.; Zhan, P.; Zhang, L.; Wan, H. Preparation of Lignin Modified Hyper-Cross-Linked Nanoporous Resins and Their Efficient Adsorption for P-Nitrophenol in Aqueous Solution and CO2 Capture. Int. J. Biol. Mac-romol. 2022, 221, 25–37.50. Poulson, B.G.; Alsulami, Q.A.; Sharfalddin, A.; El Agammy, E.F.; Mouffouk, F.; Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, L.; Jaremko, M. Cy-clodextrins: Structural, Chemical, and Physical Properties, and Applications. Polysaccharides 2022, 3, 1–31.51. Liu, C.; Cao, S.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Han, J. Cyclodextrin-Based Aerogels: A Review of Nanomaterials Systems and Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 13921–13939.52. Li, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Su, B.; Bao, Z.; Ren, Q. Inverse Adsorption Separation of CO2/C2H2 Mixture in Cyclodextrin-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 11, 2543–2550.53. Guo, T.; Bedane, A.H.; Pan, Y.; Shirani, B.; Xiao, H.; Eić, M. Adsorption Characteristics of Carbon Dioxide Gas on a Solid Acid Derivative of β-Cyclodextrin. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 4186–4192.54. Hamedi, A.; Anceschi, A.; Trotta, F.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Caldera, F. Rapid Temperature-Assisted Synthesis of Nanoporous γ-Cyclodextrin-Based Metal–Organic Framework for Selective CO2 Adsorption. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2021, 99, 245–253.55. Du, Y.; Geng, Y.; Guo, T.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Han, Z. Thermodynamic Characteristics of CO2 Adsorption on Β-Cyclodextrin Based Porous Materials: Equilibrium Capacity Function with Four Variables. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 39, 102426.56. Guo, T.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Kong, L.; Xu, J.; Xiao, H.; Bedane, A.H. Porous Structure of β-Cyclodextrin for CO2 Capture: Structural Remodeling by Thermal Activation. Molecules 2022, 27, 7375.57. Gao, H.; Li, Q.; Ren, S. Progress on CO2 Capture by Porous Organic Polymers. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2019, 16, 33–38.58. Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhai, L.; Zhao, D. Solution-Reprocessable Microporous Polymeric Adsorbents for Carbon Dioxide Capture. AIChE J. 2018, 64, 3376–3389.59. Fayemiwo, K.A.; Vladisavljević, G.T.; Nabavi, S.A.; Benyahia, B.; Hanak, D.P.; Loponov, K.N.; Manović, V. Nitrogen-Rich Hyper-Crosslinked Polymers for Low-Pressure CO2 Capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 2004–2013.60. Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Jia, X.; Fan, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Q. Hydroxyl-Based Hypercrosslinked Microporous Polymers and Their Excellent Performance for CO2 Capture. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 17259–17265.61. Abdelnaby, M.M.; Alloush, A.M.; Qasem, N.A.A.; Al-Maythalony, B.A.; Mansour, R.B.; Cordova, K.E.; Al Hamouz, O.C.S. Carbon dioxide Capture in The Presence of Water by An Amine-Based Crosslinked Porous Polymer. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 6455−6462.62. Abdelnaby, M.M.; Qasem, N.A.A.; Al-Maythalony, B.A.; Cordova, K.E.; Al Hamouz, O.C.S. A Microporous Organic Co-polymer for Selective CO2 Capture Under Humid Conditions. ACS Sus. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 13941−13948.63. Kong, X.; Li, S.; Strømme, M.; Xu, C. Synthesis of Porous Organic Polymers with Tunable Amine Loadings for CO2 Capture: Balanced Physisorption and Chemisorption. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1020.64. Sang, Y.; Shao, L.; Huang, J.; Carbonyl Functionalized Hyper-Cross-Linked Polymers for CO2 Capture. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 188.65. Sharma, N.; Ugale, B.; Kumar, S.; Kailasam. K. Metal-Free Heptazine-Based Porous Polymeric Network as Highly Efficient Catalyst for CO2 Capture and Conversion. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 737511.66. Shao, L.; Sang, Y.; Liu, N.; Wei, Q.; Wang, F.; Zhan, P.; Luo, W.; Huang, J.; Chen, J. One-step synthesis of N-containing Hy-per-Cross-Linked Polymers by Two Crosslinking Strategies and Their CO2 Adsorption and Iodine Vapor Capture. Sep. Purif. Technol, 2021, 262, 118352.67. Mohamed, M.G.; Ahmed, M.M.M.; Du, W.-T.; Kuo, S.-W. Meso/Microporous Carbons from Conjugated Hyper-Crosslinked Polymers Based on Tetraphenylethene for High-Performance CO2 Capture and Supercapacitor. Molecules 2021, 26, 738.68. Qiao, Y.; Zhan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, M.; Huang, Q.; Ke, B.T.X.; Wu, C. Amine or Azo Functionalized Hypercrosslinked Polymers for Highly Efficient CO2 Capture and Selective CO2 Capture. Mater. Today 2021, 27, 102338.69. Zhou, H.; Rayer, C.; Antonangelo, A.R.; Hawkins, N.; Carta. M. Adjustable Functionalization of Hyper-Cross-Linked Polymers of Intrinsic Microporosity for Enhanced CO2 Adsorption and Selectivity Over N2 and CH4. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 20997–21006.70. Abdelnaby, M.M.; Saleh, T.A.; Zeama, M.; Abdalla, M.A.; Ahmed, H.M.; Habib, M.A. Azo-Linked Porous Organic Polymers for Selective Carbon Dioxide Capture and Metal Ion Removal. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 14535−14543.71. Gao, Q.; Li, X.; Ning, G.-H.; Xu, H.-S.; Liu, C.; Tian, B.; Tang, W.; Loh, K.P. Covalent Organic Framework with Frustrated Bonding Network for Enhanced Carbon Dioxide Storage. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 1762–1768.72. Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, K.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Zeng, C.; Xu, H.; Wang, B.; Gao, Y. Covalent Organic Frameworks for Simultaneous CO2 Capture and Selective Catalytic Transformation. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1133.73. Lyu, H.; Li, H.; Hanikel, N.; Wang, K.; Yaghi, O.M. Covalent Organic Frameworks for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Air. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 12989−12995.74. Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Zhuang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Wei, J. New Nitrogen-Rich Azo-Bridged Porphyrin-Conjugated Microporous Networks for High Performance of Gas Capture and Storage. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 30048–30055.75. Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Du, J.; Cui, Y.; Songa, X.; Liang, Z. Conjugated Microporous Polymers Based on Biphenylene for CO2 Adsorption and Luminescent Detection of Nitroaromatic Compounds. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 9482–9487.76. Ren, S.-B.; Li, P.-X.; Stephenson, A.; Chen, L.; Briggs, M.E.; Clowes, R.; Alahmed, A.; Li, K.-K.; Jia, W.-P.; Han. D.-M. A 1,3-Diyne-Linked Conjugated Microporous Polymer for Selective CO2 Capture. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 9254–9260.77. Saber, A.F.; Chen, K.-Y.; EL-Mahdy, A.F.M.; Kuo, S.-W. Designed Azo-Linked Conjugated Microporous Polymers for CO2 Uptake and Removal Applications. J. Polym. Res. 2021, 28, 430.78. Das, S.K.; Bhanja, P.; Kundu, S.K.; Mondal, S.; Bhaumik, A. Role of Surface Phenolic-OH Groups in N-Rich Porous Organic Polymers for Enhancing the CO2 Uptake and CO2/N2 Selectivity: Experimental and Computational Studies. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 23813–23824.79. Yao, C.; Li, G.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Chang, L. Template-Free Synthesis of Porous Carbon from Triazine Based Polymers and Their Use in Iodine Adsorption and CO2 Capture. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1867.80. Tuci, G.; Iemhoff, A.; Ba, H.; Luconi, L.; Rossin, A.; Papaefthimiou, V.; Palkovits, R.; Artz, J.; Pham-Huu, C.; Giambastiani, G. Playing with Covalent Triazine Framework Tiles for Improved CO2 Adsorption Properties and Catalytic Performance. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2019, 10, 1217–1227.81. Dang, Q.-Q.; Liu, C.-Y.; Wang, X.-M.; Zhang, X.-M. Novel Covalent Triazine Framework for High Performance CO2 Capture and Alkyne Carboxylation Reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 27972–27978.82. Xu, G.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, W.; Zhang, S.; Yao, C.; Xu, Y. Porous Cationic Covalent Triazine-Based Frameworks as Platforms for Efficient CO2 And Iodine Capture. Chem. Asian J. 2019, 14, 3259–3263.83. Zhu, H.; Lin, W.; Li, Q.; Hu, Y.; Guo, S.; Wang, C.; Yan, F. Bipyridinium-Based Ionic Covalent Triazine Frameworks for CO2, SO2 and NO Capture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 8614–8621.84. Liao, C.; Liang, Z.; Liu, B.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Li, H. Phenylamino-, Phenoxy-, and Benzenesulfenyl-Linked Covalent Triazine Frameworks for CO2 Capture. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 2889–2898.85. Wessely, I.D.; Schade, A.M.; Dey, S.; Bhunia, A.; Nuhnen, A.; Janiak, C.; Bräse, S. Covalent Triazine Frameworks Based on The First Pseudo-Octahedral Hexanitrile Monomer via Nitrile Trimerization: Synthesis, Porosity, and CO2 Gas Sorption Properties. Materials 2021, 14, 3214.86. Mohamed, M.G.; Sharma, S.U.; Liu, N.-Y.; Mansoure, T.H.; Samy, M.M.; Chaganti, S.V.; Chang, Y.-L.; Lee, J.-T.; Kuo, S.-W. Ultrastable Covalent Triazine Organic Framework Based on Anthracene Moiety as Platform for High-Performance Carbon Dioxide Adsorption and Supercapacitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3174.