The graph burning problem is a relatively new combinatorial optimization problem that helps quantify a graph's vulnerability. It is defined in terms of a fundamental diffusion model.

- graph burning

- social contagion

1. Introduction

a) The neighbors of the burned vertices get burned.

b) Vertex 𝑠i gets burned.

Figure 1 shows a simple example of the burning process. The length of an optimal burning sequence for a given graph G is denoted by b(G) and is known as the burning number.

Figure 1. An optimal burning sequence for a nine vertices path is (𝑣3,𝑣7,𝑣9). The burning process of this sequence is depicted by each 𝑖 ∈ {1,2,3} with its corresponding steps a and b. Notice that vertex 𝑣3 burns all vertices at distance at most 2, vertex 𝑣7 burns all vertices at distance at most 1, and vertex 𝑣9 only burns itself.

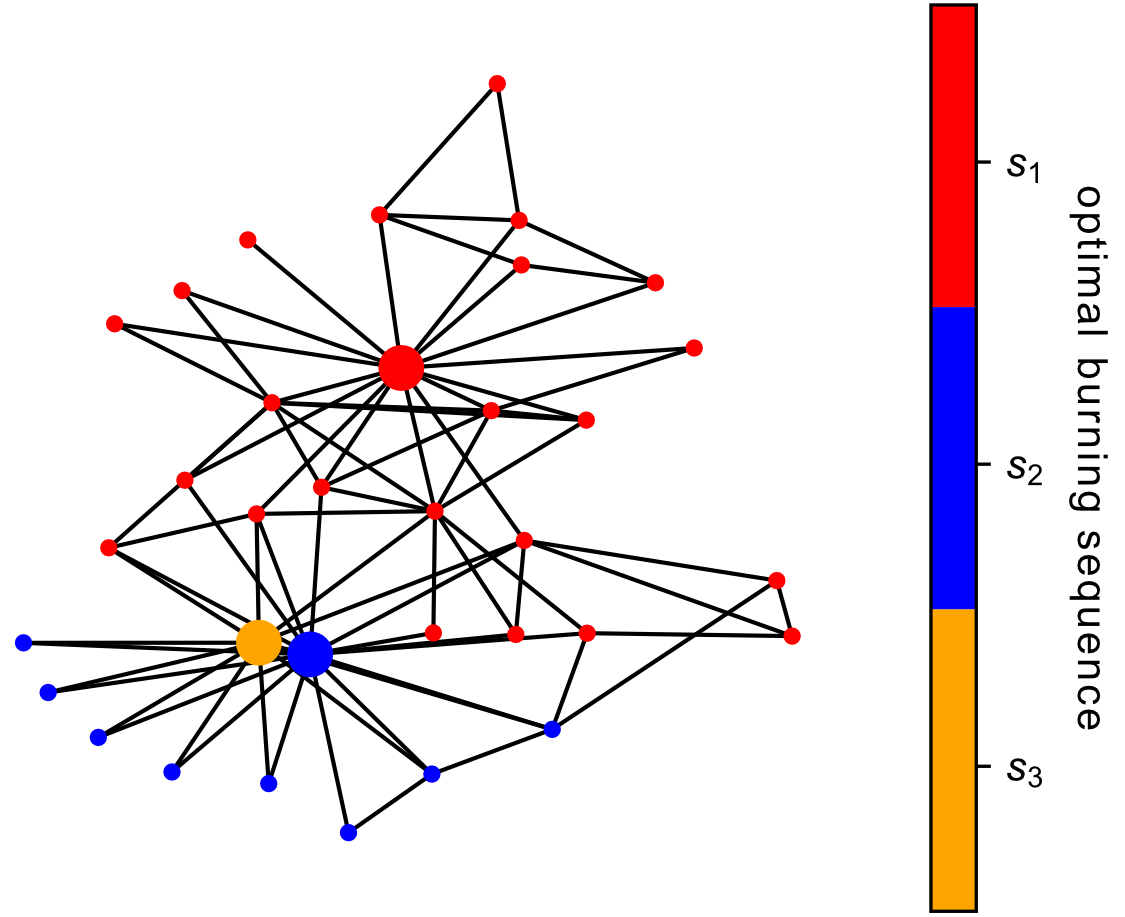

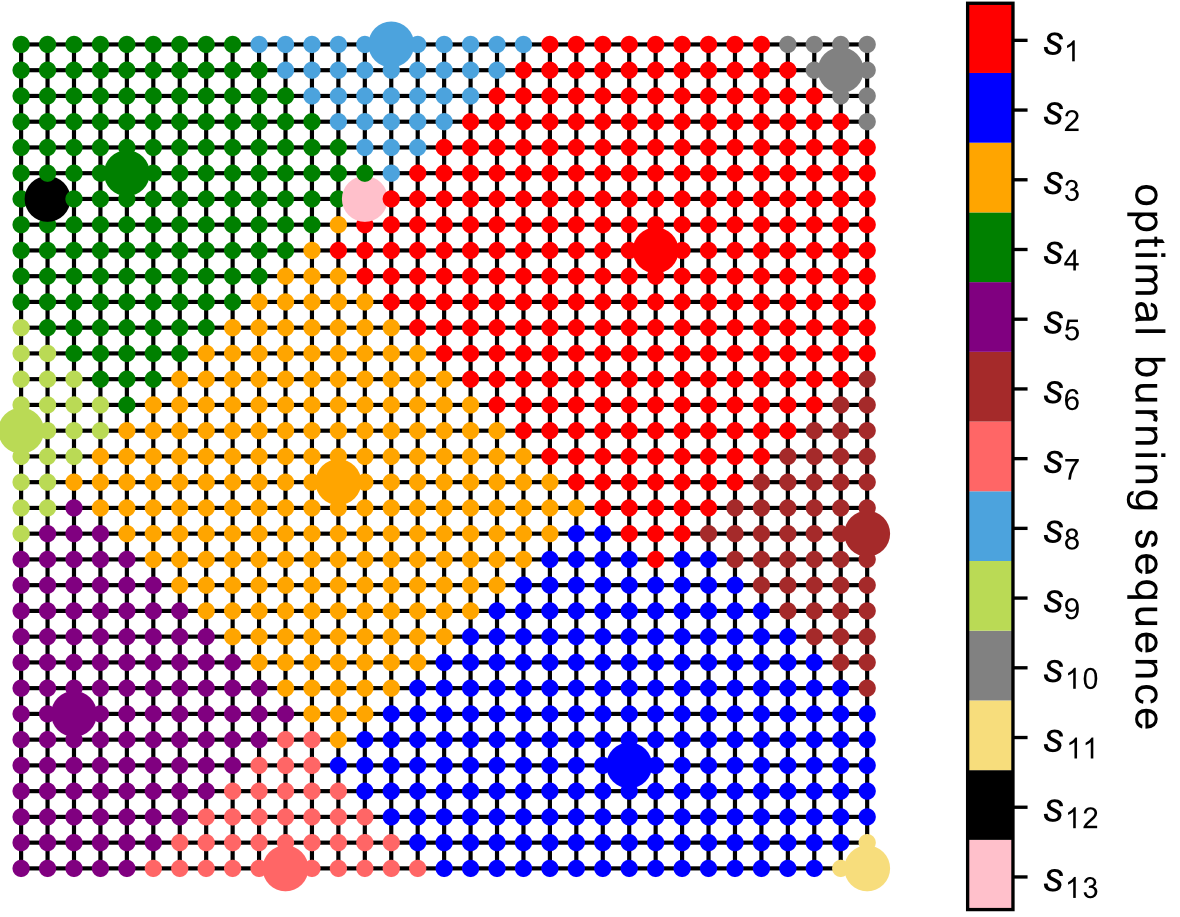

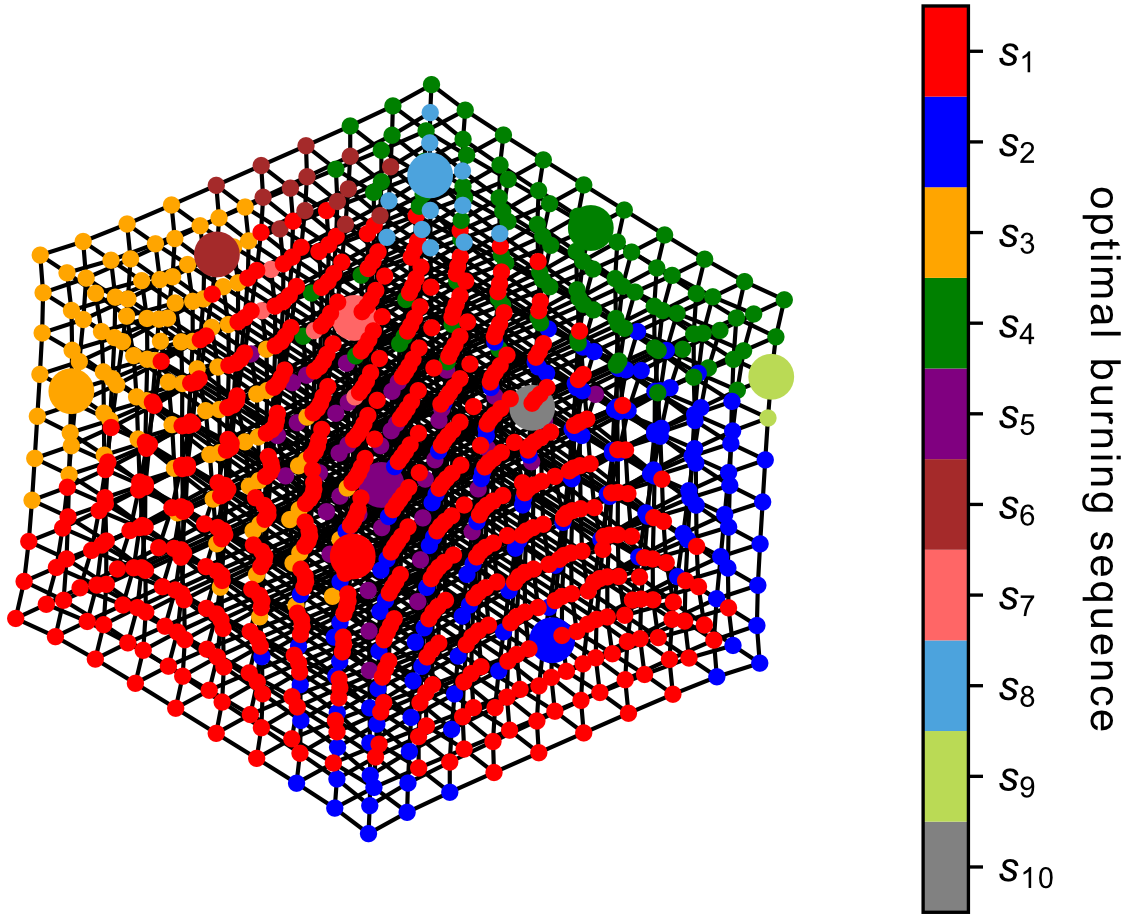

Since the above example is too simple, Figures 2-4 show the optimal burning sequence of some classical graph instances from the literature.

Figure 2. An optimal burning sequence of Zachary's karate club graph.

Figure 3. An optimal burning sequence of a 33x33 2D lattice.

Figure 4. An optimal burning sequence of a 10x10x10 3D lattice.

2. Graph Burning: Properties, Models, and Algorithms

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/math10152777

References

- Bonato, A.; Janssen, J.; Roshanbin, E. Burning a graph as a model of social contagion. In International Workshop on Algorithms and Models for the Web-Graph; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 13–22.

- Bessy, S.; Bonato, A.; Janssen, J.; Rautenbach, D.; Roshanbin, E.; Burning a graph is hard. Discret. Appl. Math. 2017, 232, 73-87, .

- Diestel, R.. Graph Theory; Springer Graduate Texts in Mathematics: Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 2.

- Šimon, M.; Huraj, L.; Luptáková, I.D.; Pospíchal, J.; Heuristics for spreading alarm throughout a network. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3269, .

- Gautam, R.H.; Kare, A.S.; Surampudi, D.B.; Faster heuristics for graph burning. Appl. Intell. 2021, 52, 1351–1361, .

- Gupta, A.T.; Lokhande, S.A.; Mondal, K. Burning grids and intervals. In Proceedings of the Algorithms and Discrete Applied Mathematics, Rupnagar, India, 11–13 February 2021; pp. 66–79

- Bonato, A.; Kamali, S. Approximation algorithms for graph burning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Theory and Applications of Models of Computation, Kitakyushu, Japan, 13–16 April 2019; pp. 74–92.

- García-Díaz, J.; Pérez-Sansalvador, J.C.; Rodríguez-Henríquez, L.M.X.; Cornejo-Acosta, J.A.; Burning Graphs Through Farthest-First Traversal. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 30395–30404, .

- Vazirani, V.V.. Approximation Algorithms; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1.

- García-Díaz, J.; Rodríguez-Henríquez, L.M.X.; Pérez-Sansalvador, J.C.; Pomares-Hernández, S.E.; Graph Burning: Mathematical Formulations and Optimal Solutions. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2777, .

- Bonato, A.; English, S.; Kay, B.; Moghbel, D.; Improved bounds for burning fence graphs. Graphs Comb. 2021, 37, 2761–2773, .

- Liu, H.; Zhang, R.; Hu, X.; Burning number of theta graphs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 361, 246–257, .

- Bonato, A.; Lidbetter, T.; Bounds on the burning numbers of spiders and path-forests. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2019, 794, 12-19, .

- Liu, H.; Hu, X.; Hu, X.; Burning number of caterpillars. Discret. Appl. Math. 2020, 284, 332–340, .

- Mitsche, D.; Prałat, P.; Roshanbin, E.; Burning number of graph products. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2018, 746, 124–135, .

- Sim, K.A.; Tan, T.S.; Wong, K.B.; On the burning number of generalized petersen graphs. Bull. Malaysian Math. Sci. 2018, 41, 1657–1670, .

- Bastide, P.; Bonamy, M.; Bonato, A.; Charbit, P.; Kamali, S.; Pierron, T.; Rabie, M. Improved Pyrotechnics: Closer to the Burning Number Conjecture. Preprint. 2022. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.10530 (accessed on 31 July 2022).

- Gonzalez, T.F.; Clustering to minimize the maximum intercluster distance. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1985, 38, 293–306, .

- Hochbaum, D.S.; Shmoys, D.B.; A best possible heuristic for the k-center problem. Math. Oper. Res. 1985, 10, 180–184, .

- Garcia-Diaz, J.; Menchaca-Mendez, R.; Menchaca-Mendez, R.; Hernández, S.P.; Pérez-Sansalvador, J.C.; Lakouari, N.; Approximation Algorithms for the Vertex K-Center Problem: Survey and Experimental Evaluation. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 109228–109245, .

- Cornejo Acosta, J.A.; García Díaz, J.; Menchaca-Méndez, R.; Menchaca-Méndez, R.; Solving the Capacitated Vertex K-Center Problem through the Minimum Capacitated Dominating Set Problem. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1551, .

- Grandoni, F.; A note on the complexity of minimum dominating set. J. Discret. Algorithms 2006, 4, 209–214, .

- Hernández-Gómez, J.C.; Reyna-Hérnandez, G.; Romero-Valencia, J.; Rosario Cayetano, O.; Transitivity on Minimum Dominating Sets of Paths and Cycles. Symmetry 2020, 12, 2053, .

- Hartnell, B. Firefighter! An application of domination. Presentation. In Proceedings of the 25th Manitoba Conference on Combinatorial Mathematics and Computing, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 29 September–1 October 1995.

- Develin, M.; Hartke, S.G.; Fire containment in grids of dimension three and higher. Discrete Appl. Math. 2007, 155, 2257–2268, .

- García-Martínez, C.; Blum, C.; Rodriguez, F.J.; Lozano, M.; The firefighter problem: Empirical results on random graphs. Comput. Oper. Res. 2015, 60, 55–66, .