The MDPI Writing Prize is an annual award supported by MDPI Author Services, which provides services including language editing, reformatting, plagiarism checks. The winners of the 2020 MDPI Writing Prize about the theme “My work and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals” are posted on Encyclopedia. In this competition, we received many excellent submissions from entrants who shared their inspirational and thought-provoking work.

- English Writing

1. Introduction

Good communication is fundamental to scientific research. With over 20 years’ experience in publishing and research communication, MDPI understands how crucial good writing is. For this reason, we have held the annual MDPI Writing Prize since 2018. It aims to promote clear, high-quality prose that powerfully communicates key scientific concepts.

2. About the Organizer

MDPI (www.mdpi.com) is a publisher of over 200 scholarly open access journals covering all disciplines. It also offers author services, including English editing, to academic authors (https://www.mdpi.com/authors/english). MDPI aims to support the rapid communication of the latest research through journals, conferences, and other services to the research community.

3. Target User

The competition is open to non-native English speakers who are Ph.D. students or postdoctoral fellows at a research institute.

4. About Awards

Essays of up to 1000 words are invited on the following topic:

“My work and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals”

1st prize (one winner): 500 CHF and certificate

2nd prizes (two winners): 250 CHF and certificate

3rd prizes (three winners): 100 CHF and certificate

Submissions should be made via email to englishediting@mdpi.com with the subject line “MDPI writing prize 2020”. Entries will be judged by the MDPI English Editing Department and evaluated on grammar and spelling, content and overall presentation.

5. Winning Prize

All award-winning works will be listed below.

5.1. From Local to a Universal Commitment to Achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

Author: Diogo Guedes Vidal

Affiliation: UFP Energy, Environment and Health Research Unit (FP-ENAS), University Fernando Pessoa (UFP), Praça 9 de Abril 349, 4249-004 Porto, Portugal

Once I start doing research I knew that the main goal was to make things done better. As a young environmental and health sociologist, believing in a more balanced and fair world, the motivation that triggered the passion for research has started since I contacted with the 2030 Agenda [1]. This ambitious and truly inspiring document contains the most powerful message: no one lefts behind. This mote has been, since them, side by side with my research goals and targets. Working in the field of environmental and health justice, namely in the urban green spaces fairly provision across all social groups, independently of their socioeconomic, cultural and ethnic background, is a small step to contribute to the UN 2030 Agenda. More than never, in a world experiencing socioenvironmental challenges, that gain more expression in urban spaces, urban green spaces research should be more intense and based on transdisciplinary approaches. The classic methods and techniques no longer make sense, once the potential to analyse the complex interaction between ecological and social systems is reduced. It is time to develop innovative approaches, to combine different perspectives and methods to be able to pursue this ambitious agenda that represents a global commitment towards a more fair and sustainable world. Urban green spaces are an essential part of SDG 11 [2], thus it is necessary to deeply understand what users feel, believe and expect from these spaces. The current scientific evidence states that these spaces are not fairly distributed within the cities: disadvantage communities are more likely to have less access to urban green spaces with quality than the wealthier ones [3,4]. This is a clear example of an environmental injustice issue that compromises the physical and mental health of these communities, and that does not lead the opportunity to promote social cohesion and empowered public open spaces [5–7]. Within this background, my research aims to contribute to a deep understanding of these dynamics, namely in the city of Porto, a coastal city in the north of Portugal. Many studies have assessed the ecosystem services potential in the urban green spaces of the city, and the conclusions are clear: urban green spaces ecosystem service potential differs from the city area and this relation is mediated by the socioeconomic and environmental vulnerability variables [4,8–10]. These results are extremely important to highlight this complex issue, but something is missing in these approaches, and that is the peoples’ voice. My work aims to fill this gap, to contribute with people perception about the urban green spaces that they visit, about its preferences, motivations and expectations. Science should be made to improve people life and in this case, urban green spaces interventions should fulfil the users, and potential users, expectations. Alongside, this research applies an innovative technique called behavioural mapping [11]. Behavioural mapping joins direct observation and practices mapping, which is a powerful combination to identify patterns of peoples habits, practices and behaviours concerning space. This small contribution from a local city in a small country of the western part of Europe intends to be a “puzzle piece” towards global commitment that we all have been called to assume. At the present, the well know saying “Thing global, acting local” is more comprehensive than never. Small actions can make big things and this should be the mindset. The United Sustainable Development Goals are more than just a vague and political document. It is undeniable that this agenda has changed the way we do science, the way that we publish and write, and, more importantly, the way that we think.

References

- United Nations Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, A/RES/70/1; Geneva, 2015.

- Vidal, D.G.; Barros, N.; Maia, R.L. Public and Green Spaces in the Context of Sustainable Development. In Sustainable Cities and Communities, Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, 2020; pp. 1–9 ISBN 978-3-319-95718-0.

- Hoffimann, E.; Barros, H.; Ribeiro, A.I. Socioeconomic inequalities in green space quality and Accessibility—Evidence from a Southern European city. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, doi:10.3390/ijerph14080916.

- Vidal, D.G.; Fernandes, C.O.; Viterbo, L.M.F.V.; Vilaça, H.; Barros, N.; Maia, R.L. Combining an Evaluation Grid Application to Assess Ecosystem Services of Urban Green Spaces and a Socioeconomic Spatial Analysis. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 1–13, doi:10.1080/13504509.2020.1808108.

- Moran, M.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; Hercky-Linnewiel, R.; Cerin, E.; Deforche, B.; Plaut, P. Understanding the relationships between the physical environment and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 79, doi:10.1186/1479-5868-11-79.

- Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, doi:10.3390/ijerph16030452.

- Gao, T.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, L.; Gao, Y.; Qiu, L. Exploring Psychophysiological Restoration and Individual Preference in the Different Environments Based on Virtual Reality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, doi:10.3390/ijerph16173102.

- Graça, M.; Alves, P.; Gonçalves, J.; Nowak, D.J.; Hoehn, R.; Farinha-Marques, P.; Cunha, M. Assessing how green space types affect ecosystem services delivery in Porto, Portugal. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 170, 195–208, doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.10.007.

- Vieira, J.; Matos, P.; Mexia, T.; Silva, P.; Lopes, N.; Freitas, C.; Correia, O.; Santos-Reis, M.; Branquinho, C.; Pinho, P. Green spaces are not all the same for the provision of air purification and climate regulation services: The case of urban parks. Environ. Res. 2018, 160, 306–313, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.10.006.

- Vidal, D.G.; Fernandes, C.O.; Viterbo, L.M.F.; Barros, N.; Maia, R.L. Healthy Cities to Healthy People: a Grid Application to Assess the Potential of Ecosystems Services of Public Urban Green Spaces in Porto, Portugal. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, ckaa040.050, doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckaa040.050.

- Ng, C.F. Behavioral mapping and tracking. In Research Methods for Environmental Psychology; Gifford, R., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Nova Jersey, 2015; pp. 29–51 ISBN 9781119162124.

5.2. Microinsurance Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Microinsurance is a type of insurance that is focused on protecting low-income people against specific risks in exchange for paying a premium that is calculated according to the likelihood and cost of the insured risk. This essay explains how microinsurance could be helpful in reaching some of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

How Can Microinsurance Help Attain United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals?

The Role of Microinsurance in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

On September 25 2015, the United Nations (UN) published the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development whose main purpose is to give an action plan for people, planet and prosperity. Moreover, it seeks to build societies which are free from fear and violence by promoting a culture of peace [1] . The Agenda was built on eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which comprise a development framework that was established by world leaders at the beginning of the new millennium [2]. By recognizing the MDGs were not fully achieved, the Agenda presents a new set of seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets that replace the MDGs [3]. Figure 1 shows the transition from the original MDGs to the new SDGs.

Figure 1: Transition from the original MDGs to the new SDGs. Obtained from [3] and [4].

As a second year Ph.D. student at the University of Lausanne in the Department of Actuarial Science (DSA), my research work is mainly focused on microinsurance (also known as inclusive insurance).

There have been multiple attempts to find the most suitable definition for microinsurance. For instance, [5] presents a detailed list with different definitions. In general, we could say that microinsurance is a type of insurance that is focused on protecting low-income people against specific risks in exchange for paying a premium that is calculated according to the likelihood and cost of the insured risk. At first sight, it might be hard to find the differences between microinsurance and traditional insurance. However, once you get more involved in the study of these fields, it is easy to come up with many dissimilarities between the two. In my opinion, even though both sectors work under the same principles, they need to be studied separately. The fundamental basis of microinsurance lies in the fact that its target market are low-income populations. Consequently, theories of traditional insurance may not apply. For example, nowadays people are used to paying high premiums for protecting themselves against specific risks. Indeed, how many of us have paid a huge amount of money for some type of insurance? I would bet that most of us have. Expecting customers to pay high premiums for a microinsurance product is inadequate. Certainly, not only could charging high premiums lead to the failure of a microinsurance product but there are many other factors to be considered. In particular, some researchers have studied the main factors affecting microinsurance demand [6] . Table 1 gives a brief overview of the sign of determination (positive or negative relationship) of these factors with microinsurance take-up.

|

Variables |

Sign of Determination |

|

|

|

Positive |

Negative |

|

Economic Factors |

||

|

Price of Insurance (including transaction costs) |

|

✓ |

|

Wealth (access to credit/liquidity) and Income |

✓ |

|

|

Social & Cultural Factors |

||

|

Risk Aversion |

|

✓ |

|

Non-performance and Basis Risk |

|

✓ |

|

Trust and Peer Effects |

✓ |

|

|

Religion/Fatalism |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Financial Literacy |

✓ |

|

|

Structural Factors |

||

|

Informal Risk Sharing |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Quality of Service |

✓ |

|

|

Risk Exposure |

✓ |

|

|

Personal & Demographic Factors |

||

|

Age |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Gender |

✓ |

✓ |

Table 1: Determinants of microinsurance demand [6]. The most common sign of determination is shown.

It is challenging to determine an appropriate design for a microinsurance product since it needs to fit some of the target population's characteristics including religious beliefs, level of education and risk exposure, among others. It is not yet clear which approach to use in the design and introduction of a new microinsurance product in a particular territory. Hence, further investigation needs to be done. In fact, some researchers have even questioned whether microinsurance overall is a helpful safety net for low-income populations [7]. Despite these statements, while it may appear redundant, I am convinced that a well designed microinsurance product is assured of a great future.

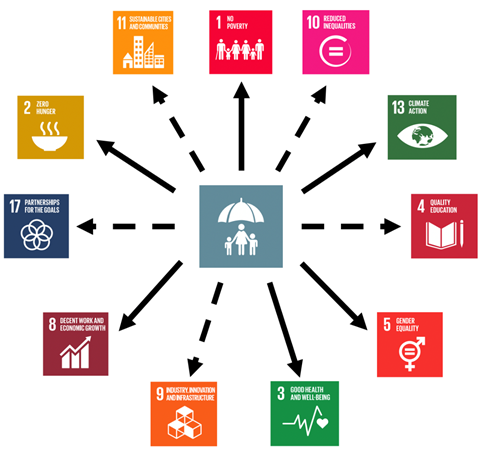

So far we have only defined microinsurance and discussed some of the challenges this sector might encounter. The question lies in how this "special" type of insurance could help achieving the SDGs. In fact, there is not a clear answer for this question. However, there have been several studies that have attempted to provide an answer. For instance, two examples are [3] and [8]. Figure 2 displays microinsurance as a primary and secondary factor in reaching eleven of the SDGs.

Figure 2: Microinsurance as a primary (solid) and secondary (dashed) contributor to the SDGs.

Some of the links shown in Figure 2 are easy to guess. For example, microinsurance works as a shock absorber against risks and therefore minimizes the losses a family might face due to the occurrence of an unfortunate event, protecting them from falling below the poverty line. Thus, it is clear how microinsurance helps in the reduction of poverty (SDG 1). In addition, this example also illustrates how this type of insurance could also be helpful in eradicating hunger (SDG 2) since a microinsurance coverage stabilizes households' income and consequently improves food security. On the other hand, some other links might be hard to determine. For instance, one might wonder how microinsurance can help improve the quality of education (SDG 4). Actually, it could be a key factor in reaching this goal. For example, let's consider the unfortunate event in which the breadwinner of a family dies. In this scenario, one can assume that a plausible solution would be to overcome the economic difficulties resulting from this event by reducing the family's expenses related to child education. Consequently, in most of the cases, the quality of education is also reduced. A life microinsurance policy for the breadwinner could have prevented this. Just as for these three SDGs, we could also find the primary or secondary link between microinsurance and the other SDGs shown in Figure 2.

The main goal of this essay is to give a brief introduction to the concept of microinsurance and to explain how it could be helpful in reaching some of the SDGs. Furthermore, we have discussed some of the main challenges this industry might encounter and highlighted the fact that there is still more to be done in order to build successful microinsurance schemes. I feel privileged to be part of the research on the microinsurance industry. I look forward to completing my studies as a Ph.D. student so that I can be part of the successful implementation of microinsurance schemes which will achieve the attainment of the SDGs.

- United Nations. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. United Nations 35 (2015).

- United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report. United Nations 72 (2015).

- Wanczeck, S., McCord, M., Wiedmaier-Pfister, M. & Biese, K. Inclusive Insurance and the Sustainable Development Goals: How Insurance Contributes to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Giz, 2017).

- United Nations Millennium Development Goals. https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/reports.shtml. Accessed: 2020-08-03.

- Blacker, J. Actuaries in Microinsurance: Managing Risk for the Underserved (Actex Publications, 2015).

- Eling, M., Pradhan, S. & Schmit, J. T. The determinants of microinsurance demand. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance - Issues and Practice 39, 224–263 (2014).

- Kovacevic, R. M. & Pflug, G. C. Does insurance help to escape the poverty trap?—A Ruin Theoretic Approach. The Journal of Risk and Insurance 78, 1003–1027 (2011).

- Gonzalez-Pelaez, A. Mutual microinsurance and the Sustainable Development Goals (University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), 2019).