Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Gastroenterology & Hepatology

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a complex multifactorial chronic inflammatory disease, that includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), having progressively increasing global incidence. Disturbed intestinal flora has been highlighted as an important feature of IBD and offers promising strategies for IBD remedies.

- inflammatory bowel disease

- gut microbiome

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), increasingly incident worldwide, is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract, mainly including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [1]. IBD patients commonly suffer from various intestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, haematochezia and vomiting, which lead to malnutrition and weight loss [2]. IBD can induce other complications, such as arthritis, cholangitis, urinary tract infections [3], and prostatitis [4]. In addition, IBD can cause stress and psychological problems in patients, resulting in decreased libido, sexual dysfunction [5], anxiety, fatigue, and even depression [6], severely impacting the quality of life of IBD patients. It is worth noting that the incidence and prevalence of IBD is escalating globally year-on-year [1]. Unfortunately, the pathogenesis of IBD remains unclear, and its etiology is believed to be triggered by multifactorial factors, such as genetics, immunity, gut microbiota, and environment, amongst others [7]. Over recent years, the gut microbiota has been recognized as a cause and consequence of IBD and has attracted much attention in IBD pathogenesis research and biological therapies. As part of the intestinal physicochemical barrier, the gut microbiota has co-evolved with the host’s intestinal environment and is involved in intestinal maintenance, immune homeostasis, metabolism balance and nutrient supplementation [8]. Alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota may contribute to a healthy or pathological gut environment, although many findings on the intestinal flora of patients with and without IBD are not uniform or standardized. Studies have indicated differences in the compositions of the gut microbiota between healthy individuals and patients with IBD, specifically in regard to the richness and diversity of specific bacterial taxa [9]. The expansion of pro-inflammatory microorganisms, including Ruminococcus gnavus and Escherichia coli, and the reduction in anti-inflammatory microorganisms, such as Bacteroidetes, Lachnospiraceae, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, are associated with the progression of IBD [10].

2. Gut Microbiota Participate in the Progression of IBD

2.1. Interactions between Gut Microbes and Barrier

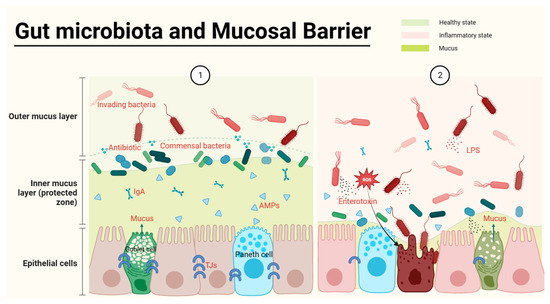

The intestinal mucosal barrier, which is the main defensive barrier against potentially harmful substances and infectious agents for the host, has been shown to closely interact with the gut microbiota [12]. The mucus provides nutrient and attachment sites for microorganisms and is associated with the production of antimicrobial mediators, including antimicrobial peptides (APMs), immunoglobulins (Ig), macrophages, etc. (Figure 1) [13]. The intestinal mucosal barrier also accommodates microbiota-derived enterotoxins, barriers, and microbial pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), including lipopolysaccharides (LPS), peptidoglycan, muramic acid, flagellin, bacterial DNA, and double-stranded RNA of viruses (Figure 1) [14]. Meanwhile, commensal microbes can increase the concentration of mucus by promoting bacteriocin production and inhibiting pathogenic bacterial survival. For instance, the increased growth of Akkermansia muciniphila (A. muciniphil), a myxophilic bacterium in abundant mucus, can become a dominant bacterium [15]. Meanwhile, A. muciniphil can also upregulate the numbers of goblet cells and mucin families of the intestinal epithelium against IBD [16]. However, the defective colonic mucus layer can aggravate the invasion of pathogens and commensal-induced inflammation in IBD [17].

Figure 1. Gut microbiota and the epithelial barrier. The healthy gut (①) is full of abundant mucus and gut microbes, with commensal bacteria producing antibiotics to defend against harmful bacteria and to spatially crowd out harmful bacteria. In the inner layer of the barrier, the intestinal epithelium is tightly interconnected, and the production of antimicrobial peptides by Paneth cells as well as Ig secreted by immune cells protects the safety of the intestinal epithelium. When harmful bacteria become dominant bacteria, they consume mucus and release PAMPs, leading to impaired intestinal epithelial tightness and inflammation (②).

The continuity of the intestinal physical barrier depends on the presence of tight junctions (TJs) in intestinal epithelial cells. The expression of TJs (claudin, occludin, zonula occludes 1 (ZO-1) and cingulin) [12] is decreased in IBD and influenced by modulation of the gut microbiota. Bifidobacteria, a typical phylum of beneficial bacteria, has been used as an indicator species of IBD exacerbation or recovery for drug effectiveness tests [18], and can increase the secretion TJs from intestinal cells [19,20], subsequently improving the symptoms of shortened intestines in IBD mice [21]. In contrast to beneficial bacteria, enterotoxins produced by invading bacteria can severely damage the epithelial structure of the host. Most of the studies jointly indicate that the abundances of adherent Escherichia coli (AIEC), Proteobacteria, Escherichia coli (E. coli), etc., were often increased in IBD, indicating that these bacteria are possible causative agents of IBD [22]. E. coli at a high level in both CD and UC patients [23] can be detected in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) [24]. AIEC, in particular, has been found to be involved in the early stages of IBD development [25]. Meanwhile, E. coli releases colibactin to damage DNA in IECs, which might be a possible reason that IBD patients are more likely to suffer from colorectal cancer (CRC) [26]. Toxin-bearing strains, or enterotoxigenic B. fragilis, cause acute and chronic intestinal disease in children and adults. For example, Enterotoxigenic B. fragilis damages the colonic epithelial barrier by inducing cleavage of the zonula adherent protein E-cadherin and initiating cellular signaling responses characterized by inflammation and c-Myc-dependent pro-oncogenic hyperproliferation [27]. In conclusion, the intestinal barrier function of IBD is tightly associated with the microbiota.

2.2. Interactions between Gut Microbes and Immune Cells

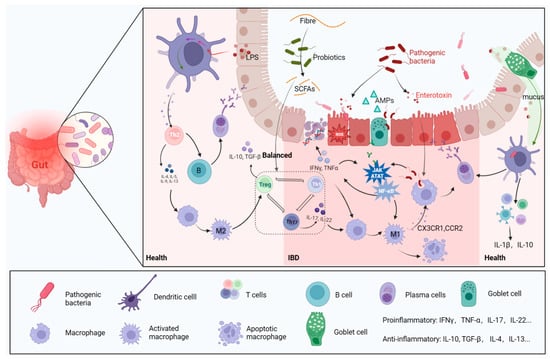

Typically, pathogens follow mucus to be captured and digested by dendritic cells and subsequently mediate more immune responses [13] (Figure 2). The gut mucosa harbors a substantial population of macrophages [28], which serve as key players in preserving gut homeostasis by responding to signals originating from the microbiota [29]. They exert significant effects on IBD by modulating pro-inflammatory (M1) or anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotypic polarization, depending on different environmental cues [30] (Figure 2). Macrophages are a double-edged sword, as their excessive activation can lead to inflammatory activation mediated by microbiota through the secretion of LPS [31]. Studies have shown that changes in gut microbiota mediated by macrophage dysfunction result in higher susceptibility to IBD [32,33]. The components of the local tissue microenvironment, such as cytokines, microbiota, microbial products, and other immune and stromal cells, more or less determine the macrophage response [28]. The damaged intestinal epithelium in IBD increases invasion of pathogenic and harmful bacteria, namely, “translocation” [34], recruiting a large number of macrophages, secreting Interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-12, IL-23 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Figure 2) [35]. The release of cytokines and chemokines from macrophages stimulates the adaptive immune response (Figure 2), which forms many classical inflammatory pathways, including the PI3K-Akt, JAK-STAT [36] and NF-κB pathways (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Gut microbes and immune cells. In a healthy intestinal environment, antigen-presenting cells transmit antigenic signals to T cells, stimulating immune responses. The following processes are engaged, and assisted, by beneficial bacteria: Th2 cell-mediated anti-inflammatory response, B-cell to plasma cell differentiation to produce antibodies, Th cells differentiating into Treg cells, and macrophage evolution into M2 type immune system. When the intestinal barrier is broken, harmful bacteria and their metabolites invade the intestine, which, in turn, induces the release of a large number of pro-inflammatory factors, leading to oxidative stress and damage to epithelial cell DNA. M1 macrophages and the inflammatory pathways they mediate are activated and contribute to the progression of IBD.

B cells and T cells are also involved in the response to signals from microbe-induced immunity activities (Figure 2) [37]. B cells can secrete immunoglobulins (Ig) to bind intestinal Proteobacteria, subsequently limiting bacterial translocation to reduce inflammatory symptoms [38]. Anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells (Tregs) and pro-inflammatory helper T cells 17 (Th17) functionally antagonize each other [39], but their balance is impaired in IBD, as shown by abundant Th17 cells in the mucosa [40]. The function of Th17/Treg cells is considered a bridge linking gut microbiota with host metabolic disorders and a dependent manner for gut microbiota to ameliorate IBD [41]. Lactobacillus can mediate the activity of regulatory T cells to ameliorate the inflammation of IBD [42,43]. The exacerbation of IBD is always accompanied by a decreased abundance of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), which may cause intestinal acid–base disturbance [44]. Lactobacillus can digest host carbohydrates to produce lactate, which plays an important role in regulating intestinal Ph and the release of inflammatory factors [45].

2.3. The Microbiota-Derived Metabolites Involved in IBD

2.3.1. Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

Dietary fiber or other nondigestible carbohydrates are digested by intestinal commensal bacteria into SCFAs [46], which are essential for intestinal integrity, by regulating luminal pH, promoting mucus production, providing fuel for epithelial cells and enhancing mucosal immune function [47]. The three most abundant microbiota-derived SCFAs are acetate, propionate and butyrate (at a ratio of approximately 3:1:1) [48]. Studies have noted that sodium acetate and sodium propionate have been demonstrated to exert inhibitory effects on the pathogenicity of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli [49]. A higher concentration of butyrate salts in the intestinal lumen can effectively counteract the adhesion and colonization of Listeria monocytogenes, resulting in a significant reduction in infection [50]. Butyrate has the ability to promote MUC2 (mucin 2) expression, leading to the restoration of the mucus barrier. Additionally, it can facilitate M2 macrophage polarization, further contributing to the repair process [51]. Sodium butyrate is a potent inhibitor of LPS-induced NF-κB, p65 and AKT signaling, inhibiting inflammation in vitro. When necessary, butyric acid can also be used as a carbon source to provide energy for the host through the β-oxidation of hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA [52]. Thus, SCFA-producing bacteria play a vital role in intestinal metabolism. Unfortunately, in the intestinal tract of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), there is consistently reduced abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria, including Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, Prevotella 9 and Coprococcus, according to Jun Hu, and the decrease in SCFA-producing bacteria is accompanied by an increase in the Escherichia-Shigella, which is a characteristic of IBD [53]. This is consistent with the trend of serum inflammatory markers in IBD patients. They may be attributed to the phenomenon of “microbial cross-feeding”, where one microbe utilizes the end products of another microbe’s metabolism [54]. The pathogenic bacteria in IBD, such as AIEC, degrade SCFAs to counteract their anti-inflammatory effects [55], ultimately leading to immune dysregulation in the intestinal tract of IBD.

2.3.2. Bile Acids (BAs)

A small fraction of free bile acids is reabsorbed directly in the gut, and a large fraction of conjugated bile acids (~95%) is absorbed in the terminal ileum [56]. During the course of circulation, primary BAs undergo various bio-transformations in the gut. Bound BAs can be hydrolyzed by bile salt hydrolase (BSH), releasing glycine or taurine and leaving free Bas. Microbiota, including Firmicutes, Clostridia, Enterococci, Listeria and Lactobacilli, as well as Actinobacteria and Bifidobacteria, can generate BSH to participate in BA metabolism [57]. Bile acids have direct toxic effects on bacteria through membrane damage and other effects to modulate the structure of the gut microbial community [58]. Among IBD patients, dysbiosis leads to a lack of secondary bile acids (SBAs) in the gut, and the beneficial effects of SBA supplementation on intestinal inflammation have been validated in animal models [59], perhaps as a result of SBAs inhibiting Th17 cell function [60].

2.3.3. Bacterial Self-Metabolites

Histamine, which is responsible for abdominal pain in IBD patients, is mainly produced by Klebsiella aerogenes with high abundance in the faecal microbiota of IBD patients [61]. Increased abundance of histamine inhibits the expression of tight junction and MUC2 proteins, reduces the level of intestinal autophagy and disrupts the function of colonic goblet cells in secreting mucus, leading to defects in the intestinal mucosal barrier [15]. Desulfovibrio, a major type of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), can trigger sulfide action resulting in frequent defecation, weight loss and increased intestinal permeability [62]. Therefore, UC patients usually have high hydrogen sulfide concentrations in the intestines. Self-metabolites of bacteria, such as colibactin and indoleamine, have DNA-damaging effects on epithelial cells and confer an increased risk of CRC [63]. The lack of tryptophan (or the increase in tryptophan metabolites in serum) has been found to worsen IBD [64]. In summary, metabolites following microbial disorders undergo a number of changes that are detrimental to IBD.

2.3.4. Vitamins

Vitamin synthesis is an important metabolic function provided by the gut microbiome: Clostridium is implicated in the synthesis of folate, cobalamin, niacin, and thiamine [65]. Bifidobacteria has been implicated in folate synthesis [66], and Bacteroides has been implicated in the production of riboflavin, niacin, pantothenate, and pyridoxine [65]. Some intestinal bacteria are highly dependent on host-supplied vitamins [67], suggesting that vitamin deficiency can affect the growth of some bacteria or that the presence of some microbes can affect the use of host vitamins [68,69]. When dietary vitamin K is deficient, the microbial community is disordered [70], resulting in to impaired blood clotting [71]. Does this mean that vitamin K deficiency is associated with intestinal bleeding symptoms in IBD? Vitamin K1 is mainly obtained from food, and vitamin K2 is mainly synthesized by gut bacteria. For neonates or healthy people, E. coli can deplete the oxygen in the intestine to help other anaerobes colonize the intestine and produce vitamin K to help the intestine resist the invasion of pathogenic bacteria [72]. Moreover, Vitamin K2 can promote the abundance of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the colon and SCFA-producing genera, such as Eubacterium_ruminantium_group and Faecalibaculum [73]. In conclusion, the gut microbial host provides multiple services, including the production of important nutrients, such as amino acids, fatty acids, and vitamins [74]. Many metabolites associated with lipids, amino acids and the tricarboxylic acid cycle are significantly altered in IBD patients, demonstrating the importance of the gut microbiota [75].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms241311004

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!