Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Microbiology

Microorganisms rule the functioning of our planet and each one of the individual macroscopic living creature. Nevertheless, microbial activity and growth status have always been challenging tasks to determine both in situ and in vivo. Microbial activity is generally related to growth, and the growth rate is a result of the availability of nutrients under adequate or adverse conditions faced by microbial cells in a changing environment.

- microbial growth

- growth rate

- microbial diversity

- near-zero growth

- stationary phas

1. Introduction

At present, it is accepted that microorganisms govern the functioning of the ecosystems and multicellular organisms on Earth [1,2,3,4,5]. The biogeochemical cycles of elements are regulated by the activity of microorganisms and a number of critical steps are only carried out by microorganisms (e.g., numerous processes involving inorganic nitrogen transformation, methane production and oxidation, oxidation of metal sulfides, iron oxidation and reduction, etc.) [6,7]. This has important consequences for the outcomes of global processes, such as climate change, because of the role of microorganisms in maintaining carbon equilibrium with the atmosphere [3,8,9,10,11]. In addition, in the last years, recent research has shown that microorganisms rule critical aspects of plant and animal (including humans) physiology [4,6,12,13]. Even psychological aspects of human behavior have been demonstrated to be dependent on the microbiome of each individual person [14,15].

Microorganisms play critical roles in our planet’s sustainability and maintenance, but how this regulation occurs and under which conditions specific microorganisms carry out expected functions require further investigation [1,16,17,18]. To this aim, the high microbial abundance and diversity existing in nature contribute to generating highly complex systems. For instance, soils have been reported to contain about 1010 bacteria g−1 [19,20] with around 30,000 different microbial taxa [19,21,22] and clean water might contain around 106 bacteria mL−1 with potentially thousands of different taxa [19,23]. Obviously, different microorganisms are represented by specific proportions of cells within communities [18,19,23,24] and their abundance and activity vary over time depending on changes in the environment. These changes are the result of dynamic physical (e.g., temperature, humidity, etc.), chemical (availability of organic and inorganic nutrients, pH, inhibition by pollutants, etc.), and biological (competition, predation, diversity, etc.) factors that are involved in the natural environment [25]. At present, a major challenge in microbiology is to be able to evaluate and understand the growth status and activity of microbial communities and the contributions of their different microbial components.

Growth is a result of microbial activity [1,26], but quantification of the growth status of a microbial population or an individual cell is an issue that requires further investigation and remains a major challenge to be solved. Bacterial growth has been frequently assessed in laboratory clonal cultures under optimal conditions [27]. Most models and studies have been based on microorganisms growing under these conditions. Nevertheless, microorganisms in nature are rarely under such ideal conditions. Because nature is a highly competitive environment, microbial growth is generally severely limited and strictly regulated [27] so than microbial abundance and biomass are in equilibrium within the carrying capacity of the ecosystem and the planet [17]. Consequently, microbial growth and functionality are time-dependent environmental conditions and researchers are barely starting to understand how biotic and abiotic factors influence the growth of microorganisms [28,29,30,31].

It is believed that microorganisms in the natural environment thrive through feast and famine cycles [26,29,30,31,32,33] due to environmental conditions and the availability of nutrients. While short pulses of nutrient abundance can occur in nature, life in the environment is assumed to mostly represent famine conditions with nutrients strictly limiting microbial growth. Although nutrients are a major factor limiting or regulating growth, numerous biotic and abiotic factors can exert stress situations that result in the activation or inhibition of microbial growth, showing differential effects among distinct microbial species. Biotic factors could include, for example, competition with other microorganisms within the same species (i.e., sharing available nutrients) or with other species (i.e., inter-species competition) over the same nutrient sources, which is a consequence of the microbial diversity at the studied ecosystem. Grazing (i.e., protistan grazers) or viral infection prevent or limit growth and have major effects on limiting the abundance of specific microbial species. Among the abiotic factors that directly limit microbial growth, one of the most drastic factors is temperature. Low temperatures might result in a highly significant reduction in growth rate, while high temperatures can also inhibit the growth of mesophiles and, for example, activate the growth of thermophiles. Each microbial taxon has a specific optimum growth temperature. As previously observed [34], microorganisms can grow within a narrower range of temperatures in nature than in the laboratory. This suggests increased potential competition among microbial species outcompeting poorly fit taxa when diverging from their optimal temperatures. There is a long list of other abiotic factors that can affect microbial growth, such as pH, water content, the presence of pollutants or growth inhibitors, etc. [35,36,37,38]. Each one of these factors, or a sum of several of them, can drastically influence growth rates.

Microorganisms are able to adapt to a very broad range of environmental conditions [28,39], reflecting the huge microbial diversity on Earth [19,28]. Microorganisms can be found practically everywhere on our planet, but every microorganism is not able to thrive everywhere [28,40]. The environmental conditions are believed to restrict microbial distribution [28,40]. Clear examples are found among the microorganisms from extreme environments (i.e., extremophiles) [40,41,42]. For example, high-temperature environments will not allow the growth of standard mesophiles and will cancel all possibility of their survival [40]; however, hyperthermophiles must grow in high-temperature environments. Similarly, halophiles inhabit high-salt environments [41] but will not prosper in freshwater environments, while non-halophiles will not survive in salterns.

In spite of the restrictive growth conditions in the environment, microorganisms are generally believed to persist through a variety of adverse conditions and regrow when appropriate conditions reappear [39,43,44,45].

Microbial communities are a composite of a large number of microbial taxa [19,23,39]. However, all of those taxa are not represented in equal numbers. Rather, some species are highly abundant and others are rare or very poorly represented, although they can be ubiquitous [19,23,24,45]. As a result, microbial growth in the environment must be considered as a net sum of growth and decay for each species integrated in the community. The fact that some microbial species grow at a relatively high rate and others grow poorly at a near-zero growth rate or even experience decay (reduction of abundance) implies that the environment is providing adequate growth conditions for some and adverse or limiting conditions for others. In addition, different taxa can have different growth capabilities, so that under optimum conditions some microorganisms are fast growers and others always show slow growth rates [19,23]. This is a variable over time and the depletion of specific nutrients or changes in abiotic or biotic factors will result in changes in the growth rates of components of microbial communities. Thus, microbial growth is a time-dependent variable within highly dynamic microbial communities [46,47]. Potential adaptations and changes in the communities occur in part due to high genome plasticity and in part due to the great adaptability of microorganisms [29,30,31,32,48,49,50]. The time dependency and time series of microbial community composition and growth need to be studied [45,46,47,49,50,51] and research attention is required to fully understand the relevance of microorganisms in nature.

As microbial diversity is huge, the mechanisms of responses and growth rates for different microorganisms under a broad range of conditions are expected to be similarly diverse. Molecular biology analysis, including genomic and transcriptomic studies, are techniques that will be required to approach these types of issues. Some examples of the mechanisms responsible for optimum and limited growth have been already reported in the literature, mainly for specific model bacteria in periods of nutrient depletion. Those responses have been studied mostly related to the development of the stationary phase of growth (and not directly related to the scenario of minimum growth rates; see below for the different stationary phases and slow growth concepts) and were reported to be controlled by master regulators [52,53,54] including, as some examples, alternative sigma factors such as RpoS and RpoH [55,56], small molecule effectors such as ppGpp [57], gene repressors such as LexA [57], and inorganic molecules, among other responses to stress and adversity including down- and upregulation of specific genes and processes such as GASP (Growth Advantage in Stationary Phase) phenotypes [52,58,59,60], SCDI (Stationary phase Contact-Dependent Inhibition) phenomena [61,62], DNA polymerases [56], error-correcting enzymes [60], movement of mobile genetic elements [49,50], metabolic slowdown [63,64,65], etc. An interesting aspect is that microorganisms under limiting or adverse conditions have been reported to activate metabolic machinery to generate secondary metabolites [66], which are not usually required for growth but can be beneficial in periods of adversity to outcompete other species or protection during periods of persistence and maintenance [66,67,68,69,70]. Some secondary metabolites have been identified and typical examples include antimicrobials or vitamins [66,67,68,69,70]. It is expected that by understanding bacterial behavior under growth-limiting conditions scientists could discover novel genes and their metabolic pathways which, at present, remain to be annotated.

Current gaps in researchers understanding of microbial growth and activity in the environment [17,18,22] limit the potential uses of microorganisms and the appropriate management of ecosystems due to lack of knowledge about the microbial world. These gaps are expected to be filled in the future so that scientists can ideally understand and manage natural ecosystems and fully comprehend their roles, implications, and the dynamic nature of the environments [18,22,29].

2. Microbial Growth

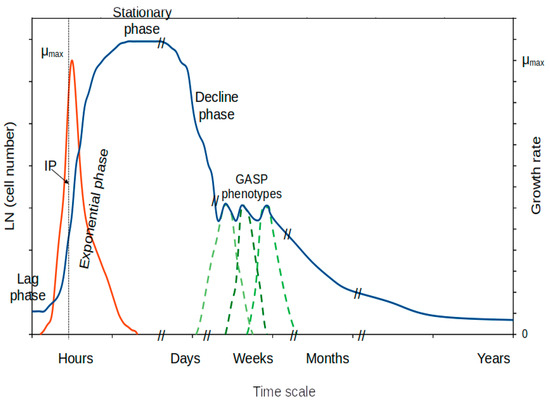

Microbial growth has been intensively analyzed and modeled using bacterial monospecific cultures in the laboratory [71,72,73]. As a consequence, the expected growth of a bacterial isolate in the laboratory is represented by a sigmoidal curve composed of differentiated and characteristic growth phases (Figure 1): the lag phase of growth (initiation of the metabolic machinery for growth), the exponential phase of growth (exponential increase in cell abundance and maximum growth rate), the stationary phase of growth (cells adapt to changing conditions due to scarcity of nutrients), and the decline (or death) phase (decrease in cell number).

Figure 1. A typical growth curve for a mono-specific microbial culture in batch showing the distinctive phases of growth with incubation time. IP, inflection point; μmax, maximum growth rate. Abundance, blue line; growth rate, red line; dashed green lines, distinct GASP phenotypes.

Different mathematical models have attempted to improve the fitting of growth curve data [72,73,74,75,76]. A typical growth curve is generally represented, for instance, by the Gompertz and logistic models [72,73,74,75,76], among other non-linear growth models. Thus, the bacterial growth curve for a clonal laboratory strain is considered to be well characterized. The difficulty starts when more complex systems (bacterial consortia, environmental samples, etc.) are evaluated for global growth in the environment or specifically for each of the numerous components of microbial communities. At this point there is a need for novel and efficient strategies to monitor bacterial growth rates.

The growth of bacteria in the laboratory appears to be a trivial matter. This is not always the case because scientists have been unable to grow a large number of different microbial taxa from natural environments [77,78]. This has been frequently quantified at around 1% of total bacteria [78] although this fraction is clearly dependent on the environment being studied and the range of culturing techniques that one is willing to assay. The fact is that a high fraction of microorganisms in the natural environment remains uncultured. Additionally, some microorganisms grow erratically and their growth is not easily predictable. Obviously, these scenarios are typical examples suggesting that new knowledge about microbial metabolism and growth conditions remains to be gathered. Examples of recent efforts to culture novel bacteria include the increased numbers of previously candidate phyla that scientists are starting to populate with cultured bacterial isolates. A couple of examples of these new phyla are Armatimonadetes (previously OP10) [79] and Saccharibacteria (previously TM7) [80].

The standard growth curve defines how microorganisms grow in a laboratory culture generally close to its optimum growth conditions. Although working in the laboratory one can design experiments to be able to measure a specific growth rate, this needs to be carefully evaluated because researchers do not know the growth rate of bacterial cells during the whole growth curve. Two points need to be mentioned. First, researchers are unable to experimentally calculate the growth rate of microorganisms growing in a culture at the time of one’s choice. Researchers could, of course, make a rough estimate of the global growth rate based on the use of well-fitting mathematical growth models as the derivative in t (time) of the mathematical function being applied.

Second, at present researchers are not able to easily analyze single-cell parameters. There have been attempts to study single-cell genomics in prokaryotes [81] and this is currently under development, becoming increasingly feasible and accurate in the last years. Researchers knowledge has a gap in understanding the variability in phenotypes, metabolism, epigenetics, and environmental responses on a per cell basis in a monospecific culture or in a microbial community in the environment [81,82]. Generally, researchers should assume that cells in a culture, above all during transitions between growth phases (i.e., from lag phase to exponential phase, or from exponential phase to stationary phase, etc.), can adopt a wide range of possibilities of growth rates (Table 1) from zero growth to the maximum achievable growth under the provided culturing conditions.

Table 1. Characteristics of different growth states of microorganisms, distinctive growth rates, functional aspects of their study, the influence of the environment, and relevance to understanding microbial responses.

| Characteristics /Relevance |

Optimum Growth | Slow Growth | Near-Zero Growth | Stationary Phase | Maintenance Metabolism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions | Optimum/ Laboratory |

Restricted growth | Severely limited growth | Nutrient depletion/growth inhibition | Maintenance /Persistence |

| Expected net growth | Optimum/maximum | ≥0.025 h−1 | <0.025 h−1 | 0–Decline | 0 |

| Degree of understanding | High | Medium/Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Environmental relevance | Poor | High | High | high | high |

| Value in taxonomy * | High | Poor | Poor | Poor | Poor |

| Discovering cell capabilities | Limited | Enhanced | High | High | High |

| Expected variability | Low | High | Very high | Very high | Medium |

| Secondary metabolite discovery | Low | High | Very high | High | Medium |

| Genome understanding | Medium | High | High | High | High |

| New gene annotation | Low/Medium | Medium/High | High | High | High |

| Microbial behavior understanding | Basic | Medium | High | High | High |

| Microbiome analysis value | Poor | Medium | High | High | Medium |

| Understanding adversity | Null | Medium | High | High | High |

| Microbial interaction potential | Poor | Medium | High | High | High |

* According to present requirements.

Unfortunately, experimental quantification of the growth rate along a typical growth curve in batch can only be determined with certainty at the inflection point of the sigmoidal curve during the exponential phase of growth (Figure 1). Beyond this point, one must assume the presence of cells at a broad variety of physiological stages. The variability existing at different phases of growth remains to be studied. Some specific experimental strategies have been designed to partially solve the issue of obtaining cells at steady-state for specific growth rates. The solutions are related to the use of continuous culturing techniques (see below).

The challenge in determining growth in a natural environmental microbial community and the growth rate of specific members of that community remains to be efficiently solved. An additional complexity level arises when these determinations should be performed, ideally frequently, over time [29,47,51] in order to analyze changes in the communities, their growth rates, and the effects of environmental factors along different time scales. It is important to highlight that slow growth rate is used herein as a relative term as a function of each microorganism’s optimum (maximum) growth rate since some are fast growers but others are much slower growing cells even under their optimum growth conditions.

A potential solution to obtain cells at different growth rates in the laboratory comes from the use of continuous culturing strategies [83]. In this case, cells are grown and the culture is stabilized at a constant growth rate (i.e., steady state) governed by the dilution rate (input of fresh medium in equilibrium with the output of grown culture) in the culturing vessel [84]. This growth rate is calculated from the dilution rate (volume of fresh medium input per unit time divided by the total volume of the culture vessel) [85,86]. The growth rate in a continuous culture does not depend on other factors such as nutrient concentration in the medium. Varying the culture medium concentration will increase or reduce cell abundance in the culture but the growth rate of the cells should remain constant.

Continuous cultures can be achieved in a chemostat [85,86] but the range of growth rates must also be within certain limits. For example, the dilution rate must be lower than the maximum growth rate of the microbial strain under the provided culturing conditions, otherwise researchers will progressively dilute the cells out of the culture. A second restriction is that cells cannot be grown at too low growth rates because of the minimal volume of fresh medium that can continuously be pumped into the culture and homogeneously distributed [86,87].

A question arises about how to achieve even lower growth rates, those that have been named near-zero growth, close to a metabolism of maintenance, with cells growing at minimum (near-zero) rates [65,87,88]. Microbial growth at very reduced growth rates (near-zero growth) is a scarcely studied field in microbiology. The solution to studying these minimum growth conditions comes from the use of a modification of the chemostat, named a retentostat. In the retentostat, a constant volume of fresh medium is input into the culture vessel, but the whole culture is not simultaneously discarded. Instead, the culture is filtered, the cells are returned to the culture vessel, and only the used medium is discarded [87,88,89,90]. This strategy leads to a progressive accumulation of cells in the culture vessel so that a higher number of cells need to share the same amount of nutrients. As a consequence, cells must compete for the available nutrients, which leads to a progressive decrease in their growth rate. Evaluating the culture biomass over time, one can calculate the growth rate of cells at a given time point in the culture [84,85]. Following this method, a cells growth doubling time of over a year could be obtained for bacteria that doubled approximately every 20 min under optimum conditions. In nature, a typical example of bacterial cells growing at a very low growth rate is deep-subsurface bacteria, which are believed to show doubling times in the range of years to centuries [91,92,93], and their metabolism and living strategies remain mostly to be understood.

At present, monitoring methods are highly limited for rapid and efficient assessment of microbial growth rates in the environment. Methodology is needed in order to determine the growth status and/or growth rate of specific bacterial taxa in complex environmental communities. Isotopic-labeling techniques measuring the incorporation of specific labeled substrates during a relatively short incubation period are among the possibilities for estimating the bacterial activity of specific bacteria and their metabolism [94,95]. Molecular methods targeting DNA and/or RNA are another option. Molecular methods involving PCR amplification (either end-point PCR or quantitative real-time PCR) provide opportunities to develop methods for these determinations. Another alternative for molecular studies is the use of fluorescently labeled nucleotide probes so that FISH (Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization) [96] can be performed to enumerate individual cells in environmental samples and eventually classify them at different growth stages. These methods are time-consuming and the information that they provide is relatively limited. At present, only a very few model species or bacterial groups have been studied [96]. Additional perspectives have been provided using NanoSIMS [82,95], which could add relevant information for single-cell functional studies on natural samples. Methods that provide important information through rapid tests and measurements will be greatly welcomed in the years to come, enabling most of the issues mentioned herein to start being solved.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms11071641

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!