Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

In a typical school day, young people need to do many tasks which rely on the ability to predict. Since prediction underpins cognitive and social skills, difficulties with prediction lead to multiple challenges to learning. Autistic people often have difficulty making predictions about other people’s behaviour, or understanding what they are required to do, contributing to high rates of anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty.

- autism

- anxiety

- intolerance of uncertainty

- prediction

- education practice

1. Causes of Anxiety

Anxiety in autistic school children is pervasive and has a considerable impact on emotional and cognitive adjustment and success [1]. Varying causes for this have been suggested, such as sensory discomfort [2], difficulties understanding other people’s behaviour (14) and communication impairment [3]. The relationship between anxiety and autistic characteristics such as repetitive behaviours, rigid thinking and difficulties with emotional regulation (ER) has been mapped in models such as those by Boulter, Freeston, South and Rogers [4] and South and Rodgers [5]. Anxiety is linked with sensory differences and alexithymia, in addition to IU, but debate continues about the nature of the relationship between these features [6]. Boulter et al. [4] suggest that people on the autism spectrum have a susceptibility to IU which leads to high levels of anxiety. They propose that the relevant question then becomes “what makes children with ASD so intolerant of uncertainty” (p. 1398). Their suggested answer to this question is that IU stems from social/environmental factors, rigidity of thought, and difficulty with emotion processing and sensory sensitivities which then lead to restricted and repetitive behaviours and anxiety. South and Rodgers [5] build on this model with the insertion of alexithymia and suggest it as a framework for future studies, with a particular focus on the causal links among the constructs. They see sensory sensitivities, alexithymia and IU as closely related to each other and as strong predictors of anxiety in ASD.

Intolerance of uncertainty has been studied in the general population in relation to generalised anxiety, social anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorders where behaviours are seen “as futile attempts to gain certainty about the future” [7] (p. 140). Boulter et al. [4] suggest that IU offers a framework for understanding autism. People experiencing IU react negatively, in terms of emotions, cognitions and behaviours, when faced with uncertainty leading to a belief that “unexpected events are negative and should be avoided” (ibid, p. 1392). Autistic people may then respond to anything which is unclear as threatening and may experience an inability to function described as ‘uncertainty paralysis’ as well as ‘uncertainty distress’ [8]. It is proposed that this provides an explanation for the predominance of special interests within the autistic population, being a way to understand everything about a specific topic so that nothing is uncertain. In this model fixed interests would not, therefore, be a core feature of ASD but would result from IU. Hodgson, Freeston, Honey and Rodgers [9] suggested that IU could be a potential mediator between autism and anxiety.

Difficulties understanding the motives and behaviours of others, related to a deficit in Theory of Mind, would contribute to a sense of unpredictability and heightened anxiety [10]. Hyperawareness to what are perceived as threats makes people more susceptible to sensory input, which is experienced as aversive [11] with IU directly impacting children’s sensory sensitivities. Wigham, Rodgers, South, McConachie and Freeston [12]) found links between sensory differences and insistence on sameness and repetitive motor behaviours and saw sensory issues predicting anxiety rather than the reverse but leave open the possibility of an alternative order to the sequence. It is possible that the link between IU and sensory sensitivity is circular and potentially a spiral of intensifying difficulties.

Emotion regulation is the focus of Conner et al. [13] who suggest that a difficulty in this regard can be a manifestation of anxiety leading to sensory sensitivity, alexithymia, IU and further anxiety. They therefore suggest a circular link where anxiety is caused by impaired emotion regulation, but that high anxiety may limit regulation, suggesting a focus on improving ER would lead to decreased anxiety. Alternatively, sensory processing difficulties are proposed to increase IU leading to anxiety and repetitive behaviours [9].

2. Prediction

Prediction is a fundamental skill which is seen as the foundation of human development and learning, for example prediction is studied within cognitive neuroscience as underpinning the development of language [14] although the directional relationship between prediction and language is debated by Rabagliati, Gambi and Pickering [15]. Sensory representations within the brain allow the determination of future actions [16] and the brain “works to model its environment, in this way ensuring that it can regulate its internal and external conditions for the sake of survival” [17] (p. 1). Furthermore, Bar [18] proposes “the cognitive brain relies on memory-based predictions, and these predictions are generated continually either based on gist information gleaned from the senses or driven by thought” (p. 280). Through perception of sensation, and by using the motor system as a feed-forward model [19], people learn to generate predictions of what is about to happen, or what is required of them. People first learn to plan their own actions through sensory-motor feedback, and use this to decode the actions of others, allowing us to predict their response to us or the environment based on previous similar experiences.

All people are driven to reduce uncertainty by making predictions and seeking control. Stress is a response to environmental changes where the individual is uncertain about what to do to ensure their wellbeing [20]. The process of learning involves making predictions and comparing to subsequent experience [21]. As we learn we tend to make frequent errors in this process and once an error has increased a stress reaction this diminishes the ability to make a correct prediction. “Clearly, if we experience the world as uncertain or ambiguous, we want to suspend learning. Conversely, if we experience it as predictable and lucid, we want to consolidate what we have learned” [20] (p. 177).

We constantly utilise our senses to work out what is happening around us and to predict what might happen next, but autistic differences in interpretation of sensory input may limit the ability to understand the environment. Van de Cruys et al. [22] explain the core characteristics of autism i.e., difficulties in executive functioning, theory of mind and central coherence, as stemming from an inability to filter relevant from irrelevant sensory input and giving too much weight to information that typically developing people would learn to deprioritise or ignore. Every situation is experienced as new and unfamiliar, leading to most cognitive resource being focused on making sense of the environment. Autistic individuals, therefore, frequently experience the world as unpredictable, as learning from experience is impeded, which then leads to persistent levels of anxiety that in turn affect day-to-day functioning, including the ability to predict [6][23][24].

Sinha, Kjelgaard, Gandhi, Tsourides, Cardinaux, Patazis, Diamond and Held [25] theorise autism as a disorder of prediction. Lack of predictive ability makes the world constantly uncertain, which leads to feelings of lack of control and the inability to take preparatory actions in any situation. This theory provides an explanation for the key features of ASD i.e., insistence on sameness, sensory hypersensitivity, difficulties in interacting with dynamic objects, difficulties with theory of mind, and islands of proficiency. For example, “rituals and an insistence on sameness may be a consequence of, and a way to mitigate, anxiety arising out of unpredictability” [25] (p. 15221). Similarly, sensory hypersensitivity is explained by a lack of ability to habituate, due to lack of prediction. This would also provide a plausible explanation for the social interaction difficulties experienced by people with autism, since many aspects of communication rely on implicit meaning, and for this people require the ability to predict [21]. Van de Cruys et al. [22], however, disagree that people with ASD have a ‘disorder’ of prediction; experiments in laboratories demonstrate appropriate prediction when interference, or ‘noise’, is kept to a minimum. Their alternative theory is that autistic people struggle to discern what are the most salient stimuli to attend to, in order to join incoming sensations with existing knowledge. This view is supported by Amoruso et al. [19] in their comparison of autistic and neurotypical children. Both groups could predict at similar levels when there was sufficient perceptual information present, but the autistic children performed less well than typical controls when the setting was more ambiguous. They conclude that “it is not sensory perception itself which is compromised in ASD but its interpretation” (ibid, p. 6). Amoruso et al. [19] also found that higher levels of anxiety reduced the ability to predict in the autistic participants. They propose that the difficulty their participants had with relying on previous knowledge to make predictions led to a view of the world as unstable which leads to a stress response. Robertson, Stanfield, Watt, Barry, Day, Cormack and Melville [26] cite disorder of prediction as an ‘emerging hypothesis’ and agree that inability to predict would cause stress. They note that this is worth further exploration, but no one has yet explicitly factored this into existing models of anxiety in ASD. By adopting disorder of prediction as a key factor in ASD researchers suggest the following working model. This is simplified to include some key aspects of autism, but not all.

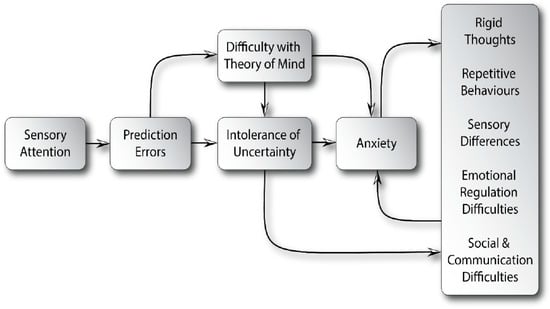

In this simple model (Figure 1), lack of focus of attention on the most salient input leads to errors in prediction, leading to a classic autistic profile of someone who struggles to understand the motives and communication of others, and who is highly anxious in social situations, which present as unpredictable and frightening. The lack of certainty and difficulties with theory of mind lead to anxiety which, in turn, leads to, and intensifies in a circular route, manifestations of autism such as repetitive behaviours and ER difficulties. Although in this model sensory difference and disturbance is seen as the outward manifestation of errors in prediction, it is also suggested that it is differences within the sensory-motor feedback loop that starts the entire process [10][16]. In this model, some students, perhaps those with less capacity for self-reflection, may experience IU and difficulties with theory of mind, leading to typical autistic characteristics, but without associated anxiety. The importance of the model in educational terms is in providing insight into strategies targeting different stages of the process.

Figure 1. Simple model of the impact of disorder of prediction in autism.

The work of Van de Cruys et al. [22] proposing a specific difficulty with prediction, together with intolerance of uncertainty [9], as a potential mediator between autism and anxiety is particularly important as we try to understand and plan support for students. Many autistic people endorse the view of autism as a difference, rather than a disorder, and the use of both ‘neurodivergent’ and ‘neurotypical’ have been widely adopted. To add an additional ‘disorder’ could be seen to be a retrograde step; however, if we are to develop effective education that supports the cognitive and social development of autistic students, teaching the ability to predict would appear to be important. Researchers therefore justify the somewhat uncomfortable focus on impairment, in order to reach an understanding of what may lead to optimal educational outcomes for autistic students. A consideration of prediction as a key skill does not preclude the strength that many autistic people have of being able to focus intently when the situation is right for them, hypothesised to lead to considerable skill and aptitude.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/educsci13060575

References

- Wood, J.J.; Gadow, K.D. Exploring the nature and function of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2010, 17, 281–292.

- Jones, E.K.; Hanley, M.; Ribya, D.M. Distraction, distress and diversity: Exploring the impact of sensory processing differences on learning and school life for pupils with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2020, 72, 101515.

- Spain, D.; Sin, J.; Lindera, K.B.; McMahon, J.; Happé, F. Social anxiety in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2018, 52, 51–68.

- Boulter, C.; Freeston, M.; South, M.; Rodgers, J. Intolerance of Uncertainty as a Framework for Understanding Anxiety in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 1391–1402.

- South, M.; Rodgers, J. Sensory, Emotional and Cognitive Contributions to Anxiety in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 20.

- Pickard, H.; Hirsch, C.; Simonoff, E.; Happe, F. Exploring the cognitive, emotional and sensory correlates of social anxiety in autistic and neurotypical adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 1317–1327.

- Norr, A.M.; Oglesby, M.E.; Capron, D.W.; Raines, A.M.; Korte, K.J.; Schmidt, N.B. Evaluating the unique contribution of intolerance of uncertainty relative to other cognitive vulnerability factors in anxiety psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 151, 136–142.

- Berembaum, H.; Bredemeier, K.; Thompson, R.J. Intolerance of uncertainty: Exploring its dimensionality and associations with the need for cognitive closure, psychopathology and personality. J. Anxiety Disord. 2008, 22, 117–125.

- Hodgson, A.R.; Freeston, M.H.; Honey, E.; Rodgers, J. Facing the unknown: Intolerance of uncertainty in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 30, 336–344.

- Tordjman, S.; Celume, M.P.; Denis, L.; Motillon, T.; Keromnes, G. Reframing schizophrenia and autism as bodily self-consciousness disorders leading to a deficit of theory of mind and empathy with social communication impairments. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 103, 401–413.

- Neil, L.; Olsson, N.C.; Pellicano, E. The Relationship Between Intolerance of Uncertainty, Sensory Sensitivities, and Anxiety in Autistic and Typically Developing Children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 1962–1973.

- Wigham, S.; Rodgers, J.; South, M.; McConachie, H.; Freeston, M. The Interplay between Sensory Processing Abnormalities, Intolerance of Uncertainty, Anxiety and Restricted and Repetitive Behaviours in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 943–952.

- Conner, C.M.; White, S.W.; Scahill, L.; Mazefsky, C.A. The role of emotion regulation and core autism symptoms in the experience of anxiety in autism. Autism 2020, 24, 931–940.

- Misyak, J.B.; Christiansen, M.H.; Tomblin, J.B. Sequential Expectations: The Role of Prediction-Based Learning in Language. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2010, 2, 138–153.

- Rabagliati, H.; Gambi, C.; Pickering, M.J. Learning to predict or predicting to learn? Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 2016, 31, 94–105.

- Wolpert, D.M.; Doya, K.; Kawato, M. A unifying computational framework for motor control and social interaction. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 2003, 358, 593–602.

- Palmer, C.; Lawson, R.P.; Hohwy, J. Bayesian approaches to autism: Towards volatility, action, and behaviour. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 521–542. Available online: https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fbul0000097 (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Bar, M. The proactive brain: Using analogies and associations to generate predictions. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 280–289.

- Amoruso, L.; Narzisi, A.; Pinzino, M.; Finisguerra, A.; Billeci, L.; Calderoni, S.; Fabbro, F.; Muratori, F.; Volzone, A.; Urgesi, C. Contextual priors do not modulate action prediction in children with autism. Proc. R. Soc. B 2019, 286, 20191319.

- Peters, A.; McEwen, B.S.; Friston, K. Uncertainty and stress: Why it causes diseases and how it is mastered by the brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 156, 164–188.

- Brown, E.C.; Brüne, M. The role of prediction in social neuroscience. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 147.

- Van de Cruys, S.; Evers, K.; Van der Hallen, R.; Van Eylen, L.; Boets, B.; de-Wit, L.; Wagemans, J. Precise minds in uncertain worlds: Predictive coding in autism. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 121, 649–675.

- Gaigg, S.; Crawford, J.; Cottell, H. An Evidence Based Guide to Anxiety and Autism; City University: London, UK, 2018.

- Green, S.; Ben-Sasson, A. Anxiety disorders and sensory over-responsivity in children with autism spectrum disorders: Is there a causal relationship? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 40, 1495–1504.

- Sinha, P.; Kjelgaard, M.M.; Gandhi, T.K.; Tsourides, K.; Cardinaux, A.L.; Pantazis, D.; Diamond, S.P.; Held, R.M. Autism as a disorder of prediction. PNAS 2014, 111, 15220–15225.

- Robertson, A.E.; Stanfield, A.C.; Watt, J.; Barry, F.; Day, M.; Cormack, M.; Melville, C. The experience and impact of anxiety in autistic adults: A thematic analysis. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2018, 46, 8–18.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!