Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Photon-counting computed tomography (PCCT) is an emerging technology that is expected to radically change clinical CT imaging. PCCT offers several advantages over conventional CT, which can be combined to improve and expand the diagnostic possibilities of CT angiography.

- photon-counting computed tomography

- computed tomography angiography

- vascular imaging

1. Introduction

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is actually considered the “gold” standard for the non-invasive assessment and diagnosis of vascular abnormalities [1,2]. CTA exploits the adequate opacification of the contrast of the target vessel following the intravenous administration of an iodinated contrast medium at high-flow rates [2]. The main advantages of CTA are the widespread availability, the short acquisition time, and the excellent spatial and temporal resolutions, while the main drawback is the exposure to ionizing radiation [1,2]. Moreover, the use of iodinated contrast media is not totally risk-free [3]. However, there is no doubt that CTA is far superior to invasive catheter-based angiographic techniques in terms of safety, costs, and even accuracy for most anatomical districts; and, even though CTA has been clinically implemented for several vascular territories, some limitations still persist and affect the reliability of the vascular assessment, especially when smaller arteries have to be assessed.

Current cutting-edge clinical CT systems are equipped with energy-integrating detectors (EIDs), which can provide images with quantitative information such as tissue-specific images and maps of the iodine concentration. With this technology, the spatial and contrast resolutions have been improving with quite small steps over the years. A different detection concept, which has gained increasing interest and is expected to substantially modify clinical CT imaging, is photon-counting detectors (PCDs). PCDs have multiple potential advantages over conventional EIDs, which can be combined to improve and expand the diagnostic possibilities of the CTA [4,5,6].

2. Photon-Counting CT Technology

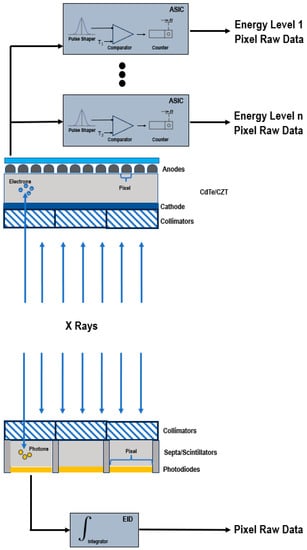

EIDs are composed of scintillator elements and septa. The scintillator converts the incident X-rays into visible light photons, that are then absorbed by a photodiode which produces an electrical signal proportional to the energy deposited and comprising also electronic noise [4]. The septa channel the light towards the sensor.

Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of EIDs and PCDs.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of a PCD (top) and of a conventional EID (bottom).

Instead, PCDs consist of a single thick layer of a semiconductor diode on which a large voltage is applied; incoming X-ray photons are directly converted into electronic signals [4,6,7]. The electrical signal is amplified and shaped, and its peak height is proportional to the energy of the individual X-ray photon.

Since PCDs do not require septa, there is no technical limitation for the pixel pitch and its size can be significantly reduced without negatively impacting the geometric detection efficiency. This translates into an increased spatial resolution, that can be exploited to generate sharper images and visualize finer details [7,8].

In conventional EIDs, the attenuation is dominated by the highest energies present in the X-ray tube spectrum. This affects the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), since the contrast between different materials is enhanced at low X-ray energies. Conversely, PCDs uniformly weight all photons and can provide a better signal to lower-energy photons, allowing for the improved signal of those substances that are highly attenuating at low energies, such as iodine and calcium, and the optimal CNR [9,10,11,12,13]. The energy-discriminating ability also represents the key to the elimination of the electronic noise achievable with PCDs. The electronics system of the detector counts how many pulses have a height exceeding a preset threshold level. By setting the lower threshold at a level higher than the electronic noise level, the signal resulting from the electronic noise, characterized by a low amplitude, is effectively discarded and only the pulses generated by incoming photons are counted. The lowest threshold energy is approximately 20 keV. Below this energy threshold, there are no X-rays in the primary beam of the X-ray tube, because they are removed by a prefilter.

The reduced electronic noise and the enhanced CNR and visualization of small objects contribute to the improvement of the dose efficiency [14,15], promoting the development of new low-dose CT acquisitions. Comparison studies between PCCT and conventional CT demonstrated that PCCT allowed for scanning with a lower radiation dose (43–50% reduction) while retaining a similar or better objective or subjective image quality [16,17,18]. Moreover, not only may be the radiation dose potentially decreased, but also the iodine contrast concentrations, which may be particularly beneficial for patients with decreased kidney function.

In addition to the weighting of energy, the other primary mechanism for employing the energy information from spectral PCCT data is material decomposition. The application of algorithms for material decomposition from a number of energy-selective images generates a set of basis image maps. The number of bases depends on the number of spectral data (N bases for N spectral data) and can be increased to N+1 by imposing mass or volume conservation constraints, which, if not correct, can cause inaccuracies [19]. Each base image map contains the equivalent material concentration displayed through a voxel-by-voxel approach. The basis material images can be displayed directly, revealing the distribution of a certain material, such as a contrast agent, or they can be processed to obtain virtual monochromatic images (VMI) [20,21,22], virtual non-contrast images [23], or material-specific color-overlay images [24]. Since EID-based CT acquires data in two energy regimes, it can accurately separate, without assumptions, one contrast agent, e.g., iodine, from the background, but it is not able to discriminate between two contrast materials with a high atomic number (high Z). PCDs differentiate photons of different energies based on the pulse-height and enable simultaneous multi-energy (N ≥ 2) acquisitions with supreme spatial and temporal registrations and without spectral overlap [25]. The increase in the number of energy regimens improves the precision in the measurement of each photon energy, resulting in better material-specific or weighted images [26] and improved quantitative imaging. Indeed, the concentrations of materials, such as contrast agents and calcium, can be quantitatively assessed, independent of acquisition parameters. Another benefit associated with the use of multiple energy measurements is the possibility to quantify elements with a K-edge in the diagnostic energy range and, consequently, to employ alternative contrast agents from iodine, such as gold, platinum, silver, bismuth, or ytterbium [27,28,29,30], or to design new types of contrast agents such as nanoparticles targeted at specific cells or enzymes [31,32,33,34]. This unique opportunity clears the way for molecular and functional CT imaging and for the simultaneous multi-contrast agent imaging. As clearly demonstrated in animal or proof-of-concept (in silico) studies, PCDs allows for the clear differentiation of more than two contrast agents in each voxel at the time of acquisition, with different pharmacokinetics within the same biological system [24,35,36,37]. For each component, it is possible to generate separate quantitative maps, showing its specific distribution, which may potentially result in additional clinical information.

Another important benefit of PCCT is the reduction of common image artifacts. The elimination of the electronic noise allows for a marked reduction of the streak and shading artifacts [13]. The constant weighting decreases the beam-hardening artifacts [38,39]. In particular, the high-energy bin image offers the highest advantages in the improved immunity to beam-hardening effects [40,41]. PCDs reduce metal and calcium blooming as a result of the improved spatial resolution (reduction in voxel size and partial voluming) and the improved material decomposition [42].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm12113798

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!