The halophyte Atriplex portulacoides (syn. Halimione portulacoides) occurs in habitats that are exposed to seawater inundations, and shows biochemical adaptations to saline and oxidative stresses. Its composition includes long chain lipids, sterols, phenolic compounds, glutathione, carotenoids,and micronutrients such as Fe, Zn, Co and Cu. The productivity of A. portulacoides in natural environments, and its adaptability to non-saline soils, make it a potential crop of high economic interest. This plant is suitable to be exploited as a functional food that is potentially able to reduce oxidative stress and inflammatory processes in humans and animals. This plant offers a valuable example of valorisation of the biodiversity for promoting the sustainability and diversification in agriculture.

- Halophyte

- Salt Marsh

- Sustainable agriculture

- Functional food

- Atriplex portulacoides

- Halimione

- active compounds

1. Introduction

Brackish wetlands and salt marshes are endangered habitats of great ecological interest, and have therefore been identified as special protection areas pursuant to Council Directive 92/43/EEC, also known as the Habitats Directive. The biodiversity occurring in these environments is characterized by peculiar adaptations to tolerate soil salinity and periodic tidal flood, especially in the case of sessile organisms, such as halophytes.

These vascular plants are endowed with uncommon biochemical defenses to protect against oxidative stress, which make them potential sources of secondary metabolites of nutritional, medical and pharmaceutical interest [1][2][3][4][5]. Atriplex portulacoides, commonly called sea purslane, is an edible halophyte that shows these traits and is potentially suitable to be cultivated for human and animal nutrition.

The introduction of innovative crops into European agrosystems is becoming an urgent need in order to counteract the heavy loss of agro-biodiversity[6], which is related to many pivotal sustainability issues, e.g., the precipitous decline of terrestrial European insects[7]. Field-based investigations have shown that biodiversity also affects the forage quality, with important economic benefits for farmers and graziers[8]. The identification of plants with high-value biochemical composition, adaptability to climate changes, and an intrinsic potential to reconnect croplands with endangered natural ecosystems is a challenging issue. Intriguingly, A. portulacoides shows all of these characteristics.

The use as forage, in addition to favoring animal welfare and promoting significant productions of this currently-uncultivated species, could allow the vehiculation of some functional compounds through food products of daily consumption, such as milk and dairy products. Importantly, A. portulacoides can be cultivated in saline and arid lands, and is thus an optimal plant for a sustainable agriculture.

2. Morphology and Systematics of Atriplex portulacoides

Atriplex portulacoides L. 1753 is a small perennial, halophile shrub, which is common along the European coasts and occurs in North Africa, Asia minor, and Western Cape province (South Africa), and has been introduced to North America[9]. Its branches are initially woody and decumbent, then soft and erected up to 20–50 cm height [10] (Figure 1), and are characterised by opposite leaves, slightly fleshy, linear-lanceolate with a full margin, and a glaucous silvery-gray colour. Its flowering period is between June and July.

Figure 1. Morphology of A. portulacoides: (A) branching and decumbent habit; (B) leaf close up; (C) freshly formed fruits in autumn.

A. portulacoides belongs to the Chenopodiacee family, whose phylogeny is complex and the object of disputed interpretations. In fact, some botanists consider Chenopodiaceae to be monophyletic because of some molecular markers[11], whereas others interpret this family as paraphyletic to Amaranthaceae, and include it therein[12].

Linnaeus described Atriplex portulacoides in 1753, but the position of this taxon was then revised by Moquin-Tandon [13], placing it under the genus Obione, and finally it was separated into the new genus Halimione by Aellen[14]. The genus name Halimione, which derives from the Greek ‘halimos’ (ἅλιμος) and means ‘seashore’ [15], is the most frequently used in literature, and is still considered valid by many authors. However, Kühn et al. [16] synonymized both O. portulacoides (L.) Moq. and H. portulacoides (L.) Aellen with Atriplex portulacoides L., re-establishing the original nomenclatorial act by Linnaeus. Even more recently, Kadereit et al.[17] resurrected the genus Halimione because of some molecular and morphological markers that are distinctive from Atriplex, which is the largest genus of the Chenopodiaceae family, with about 300 species. In this controversial background, Atriplex portulacoides is acknowledged as a senior synonym of Halimione in the International Plant Names Index, and this taxon name will be therefore adopted in the present work.

Interestingly, the species name portulacoides is obtained by combining ‘Portulaca’, a genus name of a species belonging to the family Portulacaceae, with ‘eidos’ (εἶδος), a Greek word that means ‘appearance’[15]. The species name, therefore, means ‘similar to Portulaca’, recalling the leaf similarity with the common purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.), which belongs to another family of the order Caryophyllales. Importantly, this morphological resemblance and nomenclatorial assonance have induced some non-specialists (for instance, in patent applications) to include A. portulacoides between the plants of the so-called ‘purslane family’ (see Bair et al. [18]for a correct interpretation of this group), but this association in erroneous, and is a potential source of relevant mistakes.

3. Use History and Biochemical Composition of Atriplex portulacoides

A. portulacoides can be eaten both raw and cooked[19]. The dietary use of halophytes by coastal populations dates to the late Neolithic period, as evidenced by the discovery of A. portulacoides amongst ancient charred remains of food in northern Holland[20]. In Italy, this herb was traditionally eaten in salads, or boiled. In the Marche and Sardinia regions, it entered into some recipes based on fish[21]. Its buds can be preserved in vinegar, as occurs for capers[10]. An ancient Sardinian recipe adopted by fishermen inhabiting the lagoon area of Cabras, locally called ‘mreca’, is based on mullet (Mugil cephalus) boiled in brackish water and then wrapped with fronds of A. portulacoides [22].

This plant contributes to the communities of halophytes occurring on extensive European salt marshes, where the grazing of livestock, mainly sheep, has been practiced since ancient times. In the Wadden Sea (the coast of the North Sea), natural salt marsh has been exploited as grazing lands since 2600 years ago [23]. In Mont Saint-Michel bay (France), three-quarters of the salt marsh area (30–32 km2) were grazed by 17,000 sheep in recent times[24]. In natural wetlands, not only sheep and cows graze halophytes comprising A. portulacoides, but also wild species, such as wild boars[25], geese and hares[26][27].

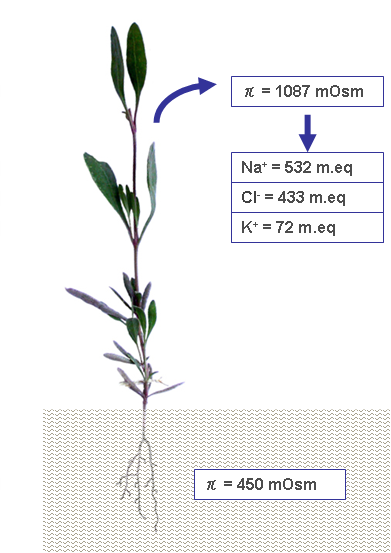

In order to overcome the negative osmotic pressure due to the salty environment, halophytes accumulate various metabolites, including quaternary ammonium compounds; ternary sulfonium compounds; proline; and soluble carbohydrates, such as sucrose, sorbitol, mannitol, and pinitol, etc. [28]. The production of osmolytes varies among different halophytes, regarding both the chemical species and relative concentrations. Glycine-betaine (a quaternary ammonium compound, also called simply ‘betaine’) and proline are organic osmolytes that are dominant in Chenopodiacee and Graminee [29]. In addition to organic osmolytes, the accumulation of some salts passively introduced with water contribute to enhance the tissue’s osmotic pressure (Figure 2).

Interestingly, A. portulacoides can sequester and/or compartmentalise metals, binding most of them to the structural components of the cell wall (pectins, lignin, cellulose, other polysaccharides), or to special proteins, said phytochelatins, [30][31][32][33][34] according to the following affinity scale: Zn > Pb > Cu > Ni > Co > Cd[35].

Figure 2. A case study of limph osmotic pressure detected in plants developed in soil with π = 450 mOsm [29]

This halophyte showed to react to the saline stress and other environmental factors by synthesising some compounds with important protective activities. Concerning its composition, particular attention should be paid to its content in poly-unsaturated fatty acids, sterols and phenolic compounds. The latter are mainly composed of sulphonated and/or glucuronated derivatives of isorhamnetin.Many of these compounds can be active also in mammalian metabolism (Table 1).

Table 1. Some compounds present in A. portulacoides and their potential nutraceutical activities

|

Category |

Compound |

Activity |

|

Carotenoids |

Lutein, zeaxanthin, antheroxanthin, violaxanthin |

Oxidative stress protection, anti-inflammatory, eye retina protection |

|

Poly-unsaturated fatty acids |

Oleic acid, linoleic acid linolenic acid |

Oxidative stress protection, cardiovascular protection |

|

Sterols |

β-sitosterol, β-sitostanol |

Hypercholesterolemia prevention |

|

Long chain alcohols |

1-octacosanol, 1-triacontanol |

Antiradicals, modulation of proNGF and NGF (parkinsonism prevention), antinflammatory |

|

Phenolic compounds |

Sulfated flavonoids |

anticancer, antinflammatory (inibition of COX2, NF-kB e MAPKs and activation of Nrf2) |

|

Phytochelatins |

Cistein, GSH, γ-Glu-Cys, (γ-Glu-Cys)n-Gly |

Oxidative stress prevention |

|

Minerals |

Mg, Fe, Zn, Mn |

Antioxidants and micrtonutrients |

4. Cultivability

Some biomass density and productivity data were estimated in the wild using different methods, amongst which the following were obtained with the Smalley method, which is the most frequently adopted method. Data concerning the epigean biomass can range between 598 g/m2 DW[34] and 1363 g/m2 DW [59], whereas (in Portugal) the values of RGR were estimated to be more favourable in winter–spring, with 7.9 mg/g/day, or 0.8% per day[34] . The productivity data were assessed in the salt marshes of some European countries: 952 g/m2/ DW was found in the Cantabrian Sea (Biscay Gulf, Spain) [35]; 790–1434 g/m2/year DW was found in a Danish salt marsh (Krabbendijke)[36].

The values above make A. portulacoides potentially suitable to be cultivated with a profitability comparable to some traditional cultivations. This plant can grow in non-saline soils, and is therefore suitable to develop in conventional agricultural lands. In the latter case, this plant seems to have the potentiality to develop under poor irrigation, allowing the exploitation of arid and even marginal saline lands. Thus, in view of the ongoing climate change, its production could offer an interesting opportunity for agricultural diversification, both for production aimed at the human diet, and to be used in properly balanced forages. As a relevant an additional advantage, this halophyte could allow to exploit marginal and saline lands currently unproductive.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/foods9111533

References

- Ksouri, R.; Ksouri, W.M.; Jallali, I.; Debez, A.; Magné, C.; Hiroko, I.; Abdelly, C. Medicinal halophytes: Potent source of health promoting biomolecules with medical, nutraceutical and food applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2012, 32, 289–326.

- Ventura, Y.; Wuddineh, W.A.; Myrzabayeva, M.; Alikulov, Z.; Khozin-Goldberg, I.; Shpigel, M.; Samocha, T.M.; Sagi, M. Effect of seawater concentration on the productivity and nutritional value of annual Salicornia and perennial Sarcocornia halophytes as leafy vegetable crops. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 128, 189–196.

- Norman, H.C.; Masters, D.G.; Barrett-Lennard, E.G. Halophytes as forages in saline landscapes: Interactions between plant genotype and environment change their feeding value to ruminants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 92, 96–109.

- Maciel, E.; Leal, M.; Lillebø, A.; Domingues, P.; Domingues, M.; Calado, R. Bioprospecting of marine macrophytes using MS-based lipidomics as a new approach. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 49.

- Barreira, L.; Resek, E.; Rodrigues, M.J.; Rocha, M.I.; Pereira, H.; Bandarra, N.; da Silva, M.M.; Varela, J.; Custódio, L. Halophytes: Gourmet food with nutritional health benefits? J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 59, 35–42.

- Pacicco, L.; Bodesmo, M.; Torricelli, R.; Negri, V. A methodological approach to identify agro-biodiversity hotspots for priority in situ conservation of plant genetic resources. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197709.

- Habel, J.C.; Samways, M.J.; Schmitt, T. Mitigating the precipitous decline of terrestrial European insects: Requirements for a new strategy. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 1343–1360.

- French, K.E. Species composition determines forage quality and medicinal value of high diversity grasslands in lowland England. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 241, 193–204.

- Chapman, V.J. Halimione portulacoides (L.). Aell. J. Ecol. 1950, 38, 214–222.

- Anoè, N.; Calzavara, D.; Salviato, L.; Zanaboni, A. Flora e vegetazione delle barene. In Gli Ambienti Salmastri della Laguna di Venezia; Soc Veneziana di Scienze Naturali: Venezia, Italy, 2001; Volume 26, pp. 9–84.

- Kadereit, G.; Borsch, T.; Weising, K.; Freitag, H. Phylogeny of Amaranthaceae and Chenopodiaceae and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 959–986.

- APG (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group) An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 181, 1–20.

- Moquin-Tandon, A. Chenopodearum Monographica Enumeratio; Loss: Paris, France, 1840; 182p.

- Aellen, P. Revision der australischen und neuseelandischen Chenopodiaceae. Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 1938, 68, 345–435.

- Acta Plantarum, from 2007+ Etimologia dei Nomi Botanici e Micologici. Available online: http://www.actaplantarum.org/etimologia/etimologia.php (accessed on 6 March 2020).

- Kühn, U.; Bittrich, V.; Carolin, R.; Freitag, H.; Hedge, I.C.; Uotila, P.; Wilson, P.G. Chenopodiaceae. In The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants; Kubitzki, K., Rohwer, J.G., Bittrich, V., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993; Volume 2, pp. 253–281.

- Kadereit, G.; Mavrodiev, E.V.; Zacharias, E.H.; Sukhorukov, A.P. Molecular phylogeny of Atripliceae (Chenopodioideae, Chenopodiaceae): Implications for systematics, biogeography, flower and fruit evolution, and the origin of C4 photosynthesis. Am. J. Bot. 2010, 97, 1664–1687.

- Bair, A.; Howe, M.; Roth, D.; Taylor, R.; Ayers, T.; Kiger, R.W. Vascular Plants of Arizona: Portulacaceae. Canotia 2006, 2, 1–22.

- Boestfleisch, C.; Papenbrock, J. Changes in secondary metabolites in the halophytic putative crop species Crithmum maritimum L., Triglochin maritima L. and Halimione portulacoides (L.) Aellen as reaction to mild salinity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176303.

- Kubiak-Martens, L.; Brinkkemper, O.; Oudemans, T.F. What’s for dinner? Processed food in the coastal area of the northern Netherlands in the Late Neolithic. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2015, 24, 47–62.

- Guarrera, P.M.; Savo, V. Wild food plants used in traditional vegetable mixtures in Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 185, 202–234.

- Mangia, N.P.; Murgia, M.A.; Fancello, F.; Mouannes, E.; Deiana, P. Tecnologia e controllo microbiologico della mreca, alimento tradizionale a base di Mugil cephalus. Ind. Aliment. 2014, 547, 21–24.

- Bakker, J.P.; Bos, D.; De Vries, Y. To Graze or not to Graze: That is the Question. In Proceedings of the 10th International Scientific Wadden Sea Symposium, Groningen, The Netherlands, 31 October–3 November 2000; Wolff, W.J., Essink, K., Kellermann, A., Van Leeuwe, M.A., Eds.; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2003.

- Laffaille, P.; Lefeuvre, J.C.; Feunteun, E. Impact of sheep grazing on juvenile sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax L., in tidal salt marshes. Biol. Conserv. 2000, 96, 271–277.

- Giménez-Anaya, A.; Herrero, J.; Rosell, C.; Couto, S.; García-Serrano, A. Food habits of wild boars (Sus scrofa) in a Mediterranean coastal wetland. Wetlands 2008, 28, 197–203.

- Bos, D.; Loonen, M.J.; Stock, M.; Hofeditz, F.; Van der Graaf, A.J.; Bakker, J.P. Utilisation of Wadden Sea salt marshes by geese in relation to livestock grazing. J. Nat. Conserv. 2005, 13, 1–15.

- Kuijper, D.P.J.; Bakker, J.P. Top-down control of small herbivores on salt-marsh vegetation along a productivity gradient. Ecology 2005, 86, 914–923.

- Bessieres, M.A.; Gibon, Y.; Lefeuvre, J.C.; Larher, F. A single-step purification for glycine betaine determination in plant extracts by isocratic HPLC. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3718–3722.

- Storey, R.; Ahma, N.; Jones, R.W. Taxonomic and ecological aspects of the distribution of glycinebetaine and related compounds in plants. Oecologia 1977, 27, 319–332.

- Reboredo, F. Zinc compartmentation in Halimione portulacoides (L.) Aellen and some effects on leaf ultrastructure. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 2644–2657.

- Sousa, A.I.; Caçador, I.; Lillebø, A.I.; Pardal, M.A. Heavy metal accumulation in Halimione portulacoides: Intra-and extra-cellular metal binding sites. Chemosphere 2008, 70, 850–857.

- Castro, R.; Pereira, S.; Lima, A.; Corticeiro, S.; Válega, M.; Pereira, E.; Duarte, A.; Figueira, E. Accumulation, distribution and cellular partitioning of mercury in several halophytes of a contaminated salt marsh. Chemosphere 2009, 76, 1348–1355.

- Válega, M.; Lima, A.I.G.; Figueira, E.M.A.P.; Pereira, E.; Pardal, M.A.; Duarte, A.C. Mercury intracellular partitioning and chelation in a salt marsh plant, Halimione portulacoides (L.) Aellen: Strategies underlying tolerance in environmental exposure. Chemosphere 2009, 74, 530–536.

- Neves, J.P.; Ferreira, L.F.; Simões, M.P.; Gazarini, L.C. Primary production and nutrient content in two salt marsh species, Atriplex portulacoides L. and Limoniastrum monopetalum L., in Southern Portugal. Estuaries Coasts 2007, 30, 459–468.

- Benito, I.; Onaindia, M. Biomass and aboveground production of four angiosperms in Cantabrian (N. Spain) salt marshes. Vegetatio 1991, 96, 165–175.

- Groenendijk, A.M. Primary production of four dominant salt-marsh angiosperms in the SW Netherlands. Vegetatio 1984, 57, 143–152.