Global food security is a worldwide concern. Food insecurity is a significant threat to poverty and hunger eradication goals. Agriculture is one of the focal points in the global policy agenda. Increases in agricultural productivity through the incorporation of technological advances or expansion of cultivable land areas have been pushed forward. However, production growth has slowed in many parts of the world due to various endemic challenges, such as decreased investment in agricultural research, lack of infrastructure in rural areas, and increasing water scarcity. Climate change adversities in agriculture and food security are increasing. The COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected global food supply chains. Economic and social instability from the pandemic contribute to long-term disturbances. Additionally, conflicts such as war directly affect agriculture by environmental degradation, violence, and breaches of national and international trade agreements. A combination of food security and climate change challenges along with increased conflicts among nations and post-COVID-19 social and economic issues bring bigger and more serious threats to agriculture.

- agriculture

- pandemic

- climate change

- global

- food security

1. Introduction

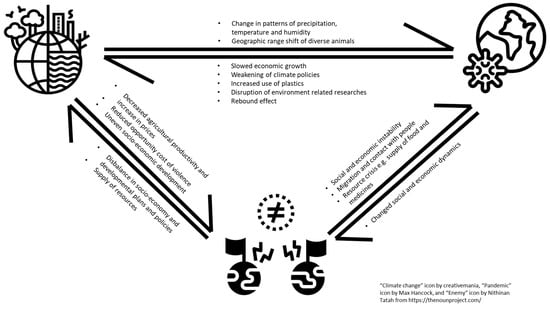

2. Conceptual Framework of Interrelation between Pandemics, Climate Change, and Conflicts

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su15108280

References

- Pinstrup-Andersen, P. Food security: Definition and measurement. Food Secur. 2009, 1, 5–7.

- Shaw, D.J. World Food Summit, 1996. In World Food Security: A History since 1945; Shaw, D.J., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2007; pp. 347–360.

- Gundersen, C.; Kreider, B. Bounding the effects of food insecurity on children’s health outcomes. J. Health Econ. 2009, 28, 971–983.

- Bhattacharya, J.; Currie, J.; Haider, S. Poverty, food insecurity, and nutritional outcomes in children and adults. Contains Contrib. Grossman Symp. 2004, 23, 839–862.

- Ivers, L.C.; Cullen, K.A. Food insecurity: Special considerations for women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1740S–1744S.

- The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022.

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Christian, G.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2013; Research Report 173; United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS): Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2504067 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Carvalho, F.P. Agriculture, pesticides, food security and food safety. Environ. Sci. Policy 2006, 9, 685–692.

- Ogundari, K. The Paradigm of Agricultural Efficiency and its Implication on Food Security in Africa: What Does Meta-analysis Reveal? World Dev. 2014, 64, 690–702.

- Mozumdar, L. Agricultural productivity and food security in the developing world. Bangladesh J. Agric. Econ. 2012, 35, 53–69.

- Samani, P.; García-Velásquez, C.; Fleury, P.; van der Meer, Y. The Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on climate change and air quality: Four country case studies. Glob. Sustain. 2021, 4, e9.

- Renee Cho. COVID-19′s Long-Term Effects on Climate Change—For Better or Worse. State of the planet. Available online: https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2020/06/25/covid-19-impacts-climate-change/ (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Zambrano-Monserrate, M.A.; Ruano, M.A.; Sanchez-Alcalde, L. Indirect effects of COVID-19 on the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138813.

- Drezner, D.W. The Song Remains the Same: International Relations after COVID-19. Int. Organ. 2020, 74, E18–E35.

- Dietz, T.; Shwom, R.L.; Whitley, C.T. Climate Change and Society. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2020, 46, 135–158.

- Fawzy, S.; Osman, A.I.; Doran, J.; Rooney, D.W. Strategies for mitigation of climate change: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 2069–2094.

- Ching, J.; Kajino, M. Rethinking Air Quality and Climate Change after COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5167.

- Carlson, C.J.; Albery, G.F.; Merow, C.; Trisos, C.H.; Zipfel, C.M.; Eskew, E.A.; Olival, K.J.; Ross, N.; Bansal, S. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature 2022, 607, 555–562.

- Mach, K.J.; Kraan, C.M.; Adger, W.N.; Buhaug, H.; Burke, M.; Fearon, J.D.; Field, C.B.; Hendrix, C.S.; Maystadt, J.-F.; O’Loughlin, J.; et al. Climate as a risk factor for armed conflict. Nature 2019, 571, 193–197.

- Burke, M.B.; Miguel, E.; Satyanath, S.; Dykema, J.A.; Lobell, D.B. Warming increases the risk of civil war in Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20670–20674.

- Oden, C. Conflict and Conflict Resolution in International Relations. Available online: https://www.projecttopics.org/conflict-conflict-resolution-international-relations.html (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Adinoyi, J.; Muliru, S.; Gichoya, F. Causes of International Conflicts and Insecurities: The Viability And Impact of Conflict Management Mechanism in International Relations. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327861068 (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Sharma, V. This Is How the Conflict between Ukraine and Russia Could Impact Climate Change. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/03/russia-and-ukraine-are-important-to-the-renewables-transition-here-s-what-that-means-for-the-climate/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Hayes, S.; Lundy, B.D.; Hallward, M.C. Conflict-Induced Migration and the Refugee Crisis: Global and Local Perspectives from Peacebuilding and Development. J. Peacebuild. Dev. 2016, 11, 1–7.

- Guadagno, L. Migrants and the COVID-19 pandemic: An Initial Analysis; Migration Research Series N° 60; International Organization for Migration (IOM): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.