1. Introduction

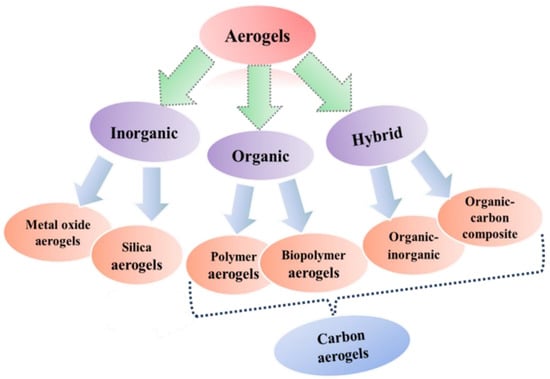

Several approaches have been used to classify aerogels based on their material forms (monoliths, granules, powders, and films), chemical composition (organic, inorganic, and hybrid), and microstructure (microporous, mesoporous, and macroporous). Different forms, compositions, and microstructures can offer different applications for and greater functionality of aerogels. The present review provides a panorama of aerogels based on their composition. Aerogels can be essentially divided into three categories: inorganic (metal and metal oxides), organic (synthetic polymers and biopolymers), and organic–inorganic hybrid materials (

Figure 1). Carbon aerogels are another important class of aerogels with different physical properties that are obtained from pyrolysis of organic and organic and inorganic composite aerogels. Carbon aerogels are characterized by excellent thermal and electrical conductivity, high porosity, and high specific surface area (>2000 m

2/g). A good introduction to carbon-based aerogels can be found in the literature [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Figure 1. Classification of aerogels based on precursor composition.

2. Inorganic Silica Aerogels

Inorganic aerogels were the first widely studied aerogels and have been applied the most [

6,

7]. Nearly all metal alkoxides are known to form porous aerogels. Synthesis of metal oxide aerogels (titanium, zirconium, tin, aluminum, etc.) with different geometries has been comprehensively reviewed by Sui and Charpentier [

8]. Among the inorganic, silica aerogels are the most widely studied commercially important class of material, and enjoy exclusive attributes such as high porosity, large surface area, and exceptionally low thermal conductivity [

9,

10,

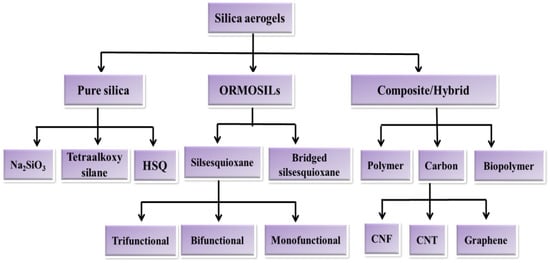

11]. The choice of precursors helps to control the properties of the final materials, thus leading to products with tailored physical and chemical properties. Overall, silica aerogels are divided into three categories derived from (1) pure silica, (2) organically modified silicas (ORMOSILs), and (3) organic–inorganic composite aerogels as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Classification of silica aerogels based on precursor composition.

2.1. Sodium-Silicate-Based Aerogels

Silica aerogels stand out as the most studied inorganic aerogels, although galaxy gel-forming materials are known in the literature. Silica aerogels have played a dominant role in both academics and industry since their first report in the 1930s [

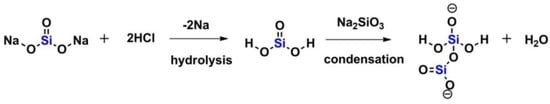

12]. The architecture of silica aerogels consists of a mesoporous structure with interconnected Si-O-Si bonds. Kistler demonstrated the first example of silica aerogels by treating an aqueous solution of sodium silicate (water glass) with hydrochloric acid. The reaction mechanism is illustrated in

Scheme 1. The aquagel obtained from this precursor is obtained using the sol-gel transition via a simple neutralization or via a two-stage reaction, followed by a supercritical drying technique.

Scheme 1. Reaction mechanisms of neutralization and condensation of sodium silicate.

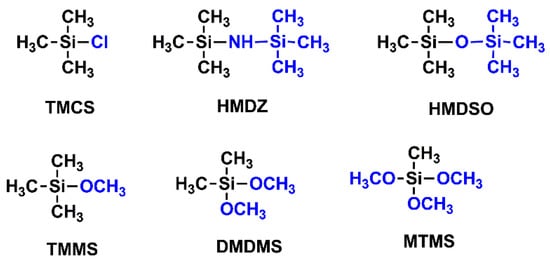

Native silica aerogels are hygroscopic; the residual Si–OH bonds on the silica surface are responsible for their hygroscopic nature. To counteract this, surface modification is required to improve the stability of aerogels. This is normally performed using silane containing hydrophobic organic groups (TMCS, HMDZ, HMDSO, TMMS, DMDMS, MTMS, etc.), which confers a hydrophobic nature to aerogels [

13,

14,

15]. These precursors react with Si–OH on the surface of the wet gel, forming methylsilyl groups. Recently, Rao has reviewed synthesis and applications of silica-aerogel-based silica aerogels [

16].

Scheme 2. Chemical structure of silylating agents used for surface modification.

Different methods to prepare hydrophobic silica aerogels were intensively studied by many authors. It was observed that TMCS drastically reduced the shrinkage of aerogels derived from sodium silicate, yielding a sturdy light-weight material with high porosity [

17,

18]. A crack-free silica aerogel was prepared using subcritical drying via surface modification of wet gels using IPA/TMCS/

n-hexane solution [

19]. The obtained aerogels possessed high porosity and low density (0.12–0.15 g/cm

3). More recently, Park and coworkers studied the effect of silylation by varying the molar ratios of silylating agents (MTMS, DMDMS, and TMMS) [

20] and further explained the silylation mechanism based on the molecular structures by considering the number of methoxy/methyl groups. They concluded that MTMS was not helpful for surface modification, whereas DMDMS showed a similar degree of silylating ability as TMCS. Aerogels modified with DMDMS exhibited high porosity (90%), high surface area (475 m

2/g), low bulk density (0.19 g/cm

3), and high hydrophobicity with a water contact angle (WCA) of 132°.

Parvathy Rao and coworkers systematically optimized conditions for synthesizing aerogels from sodium silicate by varying acid catalyst and silylating agents [

21,

22]. The physical properties of these aerogels were affected by the strength and concentration of acid [

23]. Strong acids (HCl, H

2SO

4) resulted in higher shrinkage (70–95%) and required longer gelation time. In contrast, weak acids (citric acid, tartaric acid) resulted in low shrinkage (34–50%) due to the systematic network formation during gelation. Additionally, the percentage of silylating agent in the mixture, time interval of addition, and volume of silylating mixture affected the density, porosity, and optical transparency of the aerogels [

24]. The mixture of TMCS and HMDSO provided transparent, hydrophobic (WCA 152°) aerogels with low density and low refractive index. In parallel, Bhagat and coworkers reduced the processing time (1 day) by utilizing the co-precursor method for surface modification in the hydrogel to obtain aerogel beads [

25]. The beads were obtained with pore diameters ranging from 3.2 to 4.9 nm and a specific surface area of 591 m

2/g. A simple, cost-effective method was introduced to obtain silica aerogels via surface modification of hydrogels with a very low concentration of HMDZ [

26,

27]. Initially, sodium silicate was treated with the mixture of HNO

3/HMDZ, where HNO

3 promoted the hydrolysis of HMDZ. Both surface modification and solvent exchange occur simultaneously and, as a result, superhydrophobic aerogels were obtained within 5 h.

In another report, transparent low-density silica aerogel beads were fabricated through acid-base sol-gel polymerization of sodium silicate via ball dropping method [

28]. The surface area and the pore volume of the aerogel beads increased with an increase in the volumetric percent of TMCS, and with 10%V TMCS aerogel beads with low density (0.081 g/cm

3) and high surface area (917 m

2/g) were obtained. Recently, Park et al. synthesized silica aerogels to improve the optical transmission using a two-step sol-gel process via ambient pressure drying [

29]. They observed that the aerogels prepared using 3 wt% of silica had low density (0.11 g/cm

3), low thermal conductivity (0.12 W/mK), and a surface area of 590 m

2/g. The preparation of aerogels with sodium silicate via APD is the cheapest method. However, surface modification and solvent exchange steps make this process tedious. In addition, there has not been a report on monolithic aerogels from sodium silicate via APD due to considerable crack formation. The application of monolithic silica aerogels would be enhanced by future developments in the chemical and engineering processes for solving these issues.

2.2. Tetraalkoxysilane-Based Aerogels

The process for aerogel production using the Kistler method is tedious and time consuming. The whole process of aerogel preparation from sodium silicate takes more than a week due to troublesome washing and solvent exchanging steps. There was no follow-up interest in the field of aerogels until the 1960s. Interestingly, in 1968, a research team headed by Teichner improved the process of making aerogels by dissolving tetramethoxysilane (TMOS) in methanol and was able to prepare aerogels within 12 h [

30]. This method eliminated the formation of inorganic salt and the need for a solvent exchange step. Following this, multiple research groups began working on silica aerogels for a number of different technological applications.

The hydrolysis reaction replaces the alkoxy group with hydroxy groups, and subsequently, the silanol groups form siloxane bonds (Si-O-Si) via condensation reactions along with the release of alcohol or water as byproducts. In most cases, condensation initiates in parallel with the hydrolysis reactions and persists during the whole sol-gel process. Additional linkage of silica tetrahedral species via polycondensation reactions leads to open and cyclic oligomers, which subsequently forms a network of silica gel. Intermediate species with functionalities S-OR (R is typically methyl or ethyl) and Si–OH remain in the final gel structure. Due to the relatively low reactivity of alkoxysilanes compared with other metal alkoxides, hydrolysis proceeds rapidly in the presence of acid or base catalyst. Generally, mineral acids or ammonia are used in the sol-gel reaction. Gel formation from alkoxysilanes can proceed using a one-step process in the presence of acid or base or using a two-step process in which hydrolysis and polycondensation are catalyzed separately by acid and/or base. More extended controls over the microstructure and pore size of aerogels are possible with the two-step acid–base reaction, since the kinetics and equilibrium in hydrolysis and polycondensation can be controlled separately.

Hrubesh et al. proposed a two-step process of TMOS and obtained transparent silica aerogels with a wide density range [

31]. To reduce processing time and enhance the sol-gel reactions of TMOS in supercritical CO

2 drying method, Loy and coworkers fabricated aerogels using formic acid as an alternative to water [

32]. Large monolithic hydrophobic silica aerogels were easily prepared from TMOS by controlling the molar ratio of catalysts [

33,

34]. Low-density translucent and transparent monoliths were easily obtained from TMOS. However, the toxic nature of TMOS is a barrier for its usage for industrial productions.

Concurrently, many authors studied formulation with tetraethoxysilane (TEOS), which is mild, less harmful, and a convenient precursor for the synthesis of silica aerogels [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Rao’s research team studied the effect of various parameters (such as catalyst concentration and pH) and prepared transparent aerogels using TEOS as the precursor [

39,

40]. The physical properties of aerogels derived from TEOS, TMOS, and Na

2SiO

3 were compared [

41]. They concluded that the TMOS-derived aerogel possessed excellent hydrophobicity with the highest water contact angle (149°). Later, Carroll et al. prepared silica aerogel monoliths using rapid supercritical extraction, adapting a TEOS-based recipe from Rao et al. [

42]. Light-weight aerogel materials were prepared by varying the aging period under ambient pressure, which increased the stiffness [

43]. Rao and coworkers further studied the effect of different solvents in the solvent exchange steps [

44]. Materials possessing low density, high porosity (96.5%), and low thermal conductivity (0.090 W/mK) with good optical transmission were successfully obtained from TEOS by employing HMDZ as a silylating agent. They obtained superhydrophobic aerogels (WCA 172°) when xylene was used for solvent exchange; however, the level of hydrophobicity decreased over time. Lu and coworkers developed TEOS-derived monolithic silica aerogels using ambient pressure drying through a multiple modification approach using TMCS [

45]. They concluded that the multiple treatments of the wet gel helped to reduce drying-induced surface tension force to maintain integrity and high porosity.

In 1995, Prakash and coworkers developed an ambient pressure drying protocol to prepare aerogel films using TEOS as precursor followed by surface modification with TMCS [

46,

47]. They obtained aerogel films with 98.5% porosity. This method enables the spring-back phenomenon, in which temporarily shrunk gel networks recover to their original form like a sponge. Later, Kim et al. fabricated TEOS-derived aerogels modified with TMCS using isopropanol as preparative solvent via APD. The resulting materials possessed low densities (0.041 g/cm

3) with high surface areas (1150 m

2/g) [

48]. However, the conventional APD alcogels need tedious repetitive gel washing and solvent exchange steps. To reduce the processing time, Mahadik et al. developed TMCS-modified aerogel granules derived from TEOS by using various base catalysts (TBAF, TEAF, TMAF, NH

4OH, and NH

4F) to obtain aerogel [

49]. The combination of NH

4OH and NH

4F catalysts resulted in transparent, low density (0.067 g/cm

3), hydrophobic aerogels with high optical transmittance (90%). Furthermore, they fabricated TEOS-based silica aerogels via a two-step sol-gel process and demonstrated that the surface free energy of aerogels can be tuned by modifying their surface using varied concentrations of TMCS and HMDZ silylating reagents over a wide range (5.5892 to 0.3073 mJ/m

2) [

50]. They observed an increase in WCA (123° to 155°) with a corresponding reduction in surface energy. Recently, Cok and Gizli prepared TEOS-derived silica aerogels via two-step surface modification using different silylating agents (TMCS, MTMS, MTES, and MEMO) followed by APD [

51]. Among different silanes, MTES showed a homogenous pore network, high surface area (964 m

2/g) and high hydrophobicity (WCA 137°).

2.3. Trialkoxysilane-Based Aerogels

Another interesting precursor for polysiloxane aerogels is trialkoxysilane, which empirically leads to hydridosilsesquioxane (HSQ). Since a hydrogen atom is not classified as an organic substituent, HSQ is included in this section. The hydrogen substituent is small and possibly forms hydrogen bonds with silanols. The sol-gel system of HSQ consequently shows similar behaviors to the TMOS-based one. The Si-H is vulnerable to hydrolysis during the sol-gel process. Under basic conditions, nucleophilic attack of hydroxide on the trialkoxysilane precursor results in cleavage of the Si-H moiety. This restricts the sol-gel route for HSQ to neutral or weakly acidic paths. Ozin and coworkers made considerable progress in the preparation of periodically mesoporous particles from triethoxysilane (HTES) in an acid-catalyzed system with Pluronic P123 [(poly(ethylene oxide)-

block-poly(propylene oxide)-

block-poly(ethylene oxide), denoted as EO

20PO

20EO

20] as surfactant [

52]. The resulting SiO

2 nanocomposite materials were brightly luminescent and exhibited size-controlled photoluminescence, which bodes well for the development of light emitting devices and biological sensors. Later, in 2013, Kanamori and coworkers fabricated HSQ monoliths with well-defined macropores and mesopores from trimethoxysilane (HTMS) in the presence of poly(ethylene oxide) as phase separation inducer [

53]. These HSQ materials offer surface reactivity such as reduction, which is advantageous for preparing metal nanoparticle-supported porous materials, and were shown to be promising as heterogeneous catalysts, exhibiting reusability and recyclability.

Despite their outstanding properties and potential applicability, most of the conventional silica aerogels suffer from low mechanical strength and their hydrophilic nature makes them unstable in atmospheric conditions, which makes processing and handling difficult [

54]. From the viewpoint of practical applications, monolithic materials are easier to be handled compared with powder forms. Alkoxysilanes (TEOS or TMOS) are the most favored precursors as monoliths are easily obtained. However, the alkoxysilane precursors are significantly more expensive compared with sodium silicate. The combination of sodium silicate and ambient pressure drying is the most promising route to produce silica aerogels at low cost. At present, silica aerogel granules are manufactured by Cabot Aerogels on an industrial scale using sodium silicate [

55].

3. Organically Modified Silica Aerogels

Hybridization is a promising way to improve the mechanical properties of silica aerogels to extend their applications. Nevertheless, synthesis of organic–inorganic hybrids from organotrialkoxysilane is challenging due to the hydrophobicity of condensates and steric effects exerted by the organic moiety. Therefore, a significant fraction of recent studies have been associated with the development of hybrid aerogels [

57,

58,

59,

60]. These hybrid materials are categorized into two classes, class I and class II, depending on the connectivity between organic and inorganic counterparts [

60,

61]. Class I hybrid aerogels are prepared by mixing two separate organic and inorganic compounds via sol-gel process. These composites are the results of physical interactions such as van der Waals forces, electrostatic forces, and hydrogen bonding between organic and inorganic phases [

62].

The class II hybrid materials involve strong chemical interactions (such as covalent and iono-covalent bond) between organic and inorganic phases. There are two types of hybridization strategies: (1) employment of organoalkoxysilanes as a precursor, and (2) formation of composites with polymers [

63] or structural supports. Silica aerogels can be strengthened by introducing organic groups using a co-precursor into an inorganic framework through a Si-C bond [

64]. The resulting hybrid materials are termed “Organically Modified Silica” (ORMOSILs) or organically modified ceramics. The organic group, which comprises around 40–60% of the material, remains an integral part of the network. They can be varied in terms of the length, rigidity, and geometry of the substituent, thus providing an opportunity to modulate the bulk properties of aerogels. Typical examples of ORMOSILs include silsesquioxanes and bridged silsesquioxanes, depending on the precursor used. The synergetic combination of organic and inorganic moieties in a single-phase material provides unique possibilities to tailor the thermal, mechanical, and optical properties. The presence of nonpolar alkyl or aryl groups attached to a silica-based network may result in flexible three-dimensional networks. The general preparation method, properties, and applications of organically modified aerogels can be found in some outstanding review papers [

65,

66].

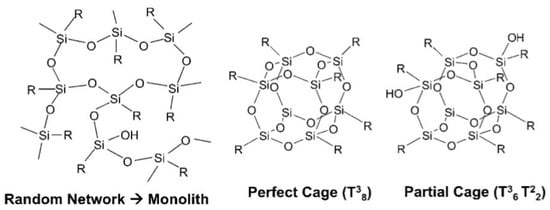

3.1. Silsesquioxanes

Among the family of hybrid aerogels, silsesquioxane are based on compounds with RSiO

1.

5 repeat units, and this group has grown dramatically [

67,

68,

69]. The first commercialization of silicones began with silsesquioxane chemistry. Silsesquioxanes derived from trifunctional silanes structurally exhibit siloxane networks or cages with varied pendent groups (

Figure 4). Typically, there are two types of materials: polymers based on random networks (T resins) and oligomeric molecules known as polyhedral oligosilsesquioxane (POSS). The structures of monofunctional (R

3SiX, X = alkoxy, halogen, etc), difunctional (R

2SiX

2), and trifunctional (RSiX

3) organosilane used in the preparation of silsesquioxane are described in

Scheme 3. All these precursors are characterized by the presence of Si–O covalent bonds. The network material can be formed from RSiX

3 via condensation with tetrafunctional monomers such as TEOS or TMOS. The resulting morphology of hybrid material is modulated via RSiX

3/TEOS ratio. Due to high thermal and mechanical stabilities with variable porosity, silsesquioxanes are used in various applications such as ionic liquids [

70], organic semiconductors for electronics [

71], electrolytes for lithium ion batteries [

72], water desalination [

73], gas/liquid phase separation [

74], and optical materials [

75].

Figure 4. Typical structure of silsesquioxanes derived from trialkoxysilanes.

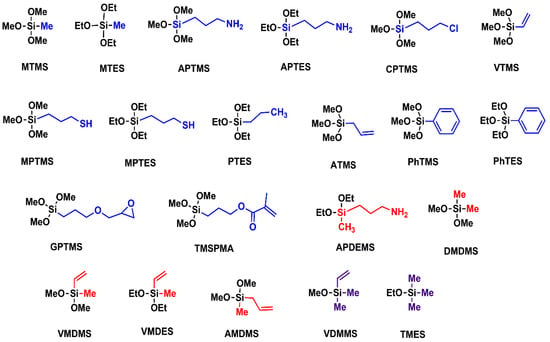

Scheme 3. Organosilane precursors used in the preparation of silsesquioxanes.

In an altogether different approach to develop low-density aerogels, Novak et al. introduced the concept of interpenetrating networks of inorganic and organic moieties. Polyvinylpyridine (PVP) was introduced into silica networks through the addition of CuCl

2, and the organic polymer was generated in situ via radical polymerization of a vinyl monomer [

76]. Later, Kramer et al. successfully reinforced silica aerogels with a silicone using TEOS with varying amounts of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) via a two-step acid/base catalyzed process [

77]. These organically modified aerogels displayed optical transparency, improved mechanical strength, and possessed a surface area of up to 1200 m

2/g.

The gelation behavior of trialkoxysilane is much more complicated than that of tetraalkoxysilanes due to cyclization and premature phase separation [

78]. In most cases, using only trialkoxysilane as a precursor results in failure to form a monolithic gel because of the steric hindrance and hydrophobicity derived from the organic moiety [

79].

Schubert and Hüsing fabricated a series of hybrid aerogels using tetraalkoxysilane with a broad range of trialkoxysilanes including MTMS, MPTMS, APTMS, GPTMS, and MAPTMS [80,81,82,83]. They observed higher shrinkage and longer gelation time with an increasing fraction of trialkoxysilanes due to the incomplete hydrolysis and condensation reaction of the trialkoxysilanes. Moreover, in most cases, aerogels became turbid with the increasing concentration of trifunctional monomers due to cyclization and macroscopic phase separation in polar solvents [79,84], which prevented the formation of 3D random networks and resulted in the formation of domains larger than submicrons, which lowered the visible-light transmittance.The fabrication of flexible superhydrophobic aerogels has attracted extensive interest from a practical point of view. In 2006, Rao et al. reported a novel synthetic approach to prepare flexible aerogels using an MTMS precursor. The nonpolar methyl groups present in MTMS impart hydrophobicity, and the reducing number of Si-O-Si bonds leads to fewer cross-linked structures. They used a

mixture of trialkoxy and tetraalkoxysilanes to develop transparent, superhydrophobic aerogels [85,86,87,88]. Generally, MTMS-derived aerogels are prepared via a one-step base catalyzed or two-step acid-base catalyzed sol-gel process. It was observed that the two-step process is more suitable to obtain a monolithic polysiloxane network. However, increasing the molar ratio of MTMS/TMOS decreased the transparency and

specific surface area with a Young’s modulus of 0.03–0.06 MPa due to

enhanced phase separation. In later studies, Bhagat et al. produced monolithic MTMS-derived aerogels via ambient pressure drying, but they did not provide a detailed discussion on the flexibility performance [

89].

When employing MTMS as a single precursor, the concentration of MTMS influences the mechanical properties of the aerogels, and Young’s modulus decreased from

0.141 to

0.0343 MPa [90]. As the molar ratio

of MeOH/MTMS

increased from 14 to 35, there was an increase in the flexibility and a decrease in the density. This occurred because the silica networks were separated from each other and linear networking was enhanced. These random networks derived from MTMS

are termed as polymethylsilsesquioxane (PMSQ). They are composed of polymeric random networks with the ideal chemical formula CH3SiO1.5. Although both silica and PMSQ aerogels consist of Si-O-Si bonds in their networks, their properties differ in mechanical durability due to the incorporated methyl groups. Recently, Borzecka et al. investigated the kinetics of formation of MTMS-based silica aerogels prepared using sol-gel polymerization and described the dynamics of the condensation reaction [

91]. They concluded that both a numerical model and experimental test can be used in the mass prediction of aerogels during modification of the materials.

Recently, Yun and coworkers prepared large-sized (240 cm

3) monolithic MTMS-based aerogels via facile sol-gel method [

92].

The resulting APD dried superhydrophobic

aerogels showed macropore structures with low density, low thermal conductivity (0.036 W/mK), and good thermal stability. It was observed that the Young’s modulus of the aerogels increased (0.043 to 1.102 MPa) with an obvious increase in the density (0.075 to 0.14 g/cm

3). The simple fabrication method and the superior performance of these aerogels

make them useful in long-term and large-scale thermal applications.

Hydrophobic aerogels based on TEOS are prepared by incorporating ETES and PhTES as co-precursors with varied molar ratios [93,94]. Depending on the molar ratio (<0.1), transparent monolithic aerogels were obtained.

In pursuit of aerogels with improved mechanical properties, Roig et al. integrated organically modified silica aerogel by using TMOS/MTMS and TMOS/TMSPMA [

95]. They found that surface area increased with an increase in the concentration of MTMS and the contact angle reached 160° in the TMOS/MTMS system. Meanwhile, TMSPMA-based aerogels did not withstand high temperature supercritical drying. Macroporous PMSQ monolithic materials with various sol-gel systems (acid/base and acid/acid method) containing MTMS were fabricated by Dong et al., leading to improvements in terms of controlling phase separation and gelation time [

96,

97,

98]. They were able to produce bimodal and trimodal PMSQ monoliths, depending on the conditions employed.

The practical applications of aerogels are limited due to the reduced transparency and the lack of control over thickness and porosity. Incorporating trifunctional monomers with alkyl trialkoxysilanes makes the resultant aerogel surface hydrophobic, but sacrifices the transparency and surface area due to induced macroscopic phase separation. In 2007, Kanamori et al. explored phase separation-gelation behavior of MTMS-based aerogels using various ionic (CTAC, CTAB) and nonionic (Pluronic F127) surfactants and obtained transparent PMSQ aerogels with uniform porosity for the first time [

99,

100,

101,

102]. Cationic surfactant CTAB interacts with the silica domain by settling the polar head groups toward the silica, which effectively suppresses the macroscopic phase separation, while nonionic surfactants facilitate hydrogen bonding between the silanol groups (Si–OH), and urea helps to accelerate the polymerization of MTMS by raising the solution pH. Because of the elastic nature of the PMSQ network, the PMSQ aerogels obtained displayed reversible “spring-back” behavior against compressive deformation. They also exhibited high porosities (94%) with low bulk densities (0.1 g/cm

3). Later, Kanamori and coworkers explored the effects of the molecular structure of nonionic surfactants on the properties of the resultant PMSQ aerogels by employing surfactants of different molecular weights [

103]. They concluded that transparent aerogels cannot be obtained from surfactants with very low molecular weight (L35) or very high hydrophobicity (P123).

Xiaodong and coworkers produced flexible aerogels by applying MTMS/TEOS co-precursors and CTAC as surfactant via ambient pressure drying technique [

104]. The resulting aerogels showed excellent flexibility, and exhibited a hydrophobic nature (CA of 153.9°) with a superior thermal insulating property. More recently, Li and coworkers developed MTMS-based monolithic silica aerogels in the presence of CTAB as surfactant in pure water within 4 h [

105]. They also investigated the effect of MTMS/H

2O ratio, CTAB content, and NH

3·H

2O concentration on the properties of aerogels. They observed that aerogels with higher volume ratios of H

2O/MTMS exhibit larger Young’s modulus and smaller compressive stress because of the difference in microstructure. This process could help in the fast massive production of aerogels.

There are numerous reports on aerogels with trifunctional alkoxysilane, but very few reports on mono- and dialkoxysilanes because of their tendency toward phase separation at levels that are too high, arising from the hydrophobicity of the network. To obtain low-density bendable materials, Hayase et al. developed “marshmallow-like” aerogels from an MTMS-dimethyldimethoxysilane (DMDMS) co-precursor system using CTAC surfactant [

106,

107,

108]. As DMDMS concentration increased, samples recovered their original shape after unloading, when compressed to 80% of their original size. These marshmallow-like gels showed bending flexibility and can be used in oil–water separation. Variations of the marshmallow-like gels have been demonstrated by using VTMS, MPTMS, and PhTMS, among others. The marshmallow-like gel can also be tailored in a powder form [

109]. A more advanced surface design can be achieved when precursors with reactive groups are employed to prepare flexible aerogels. The co-condensation reaction between VTMS and VMDMS followed by the thiol-ene reaction on the surface is illustrated in

Scheme 4. Perfluoroalkyl groups were introduced for surface modification [

110]. These flexible material designs are beneficial for developing multifunctional porous materials.

The use of surfactants suppresses the phase separation and, as a result, flexible, superhydrophobic, and transparent aerogels were obtained, but in general surfactants are very expensive and the residual surfactant causes serious shrinkage and cracks in the monoliths during drying. Therefore, Kanamori et al. developed a surfactant-free method to obtain hydrophobic PMSQ aerogels by copolymerizing with N-[3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium chloride (TMAC), which helps in suppressing undesirable phase separation [

111]. The obtained materials revealed low-density, high visible-light transmittance, and good thermal insulation (0.0136 W/mK) properties equivalent to those prepared in the presence of surfactant.

To ascertain the effect of the molar concentration of precursor and drying parameters on the properties of aerogels, Durães et al. fabricated aerogels by varying the molar ratio of MTMS, MTES, and ETMS [

112,

113,

114]. The ETMS co-precursor led to a significant increase in the product density with a reduction in surface area. Therefore, MTMS is a more suitable precursor, yielding hydrophobic aerogels with low density, average surface area (400 m

2/g), and good flexibility. Aerogels prepared from MTMS as a precursor followed by ambient pressure drying not only maintain excellent monolithic properties, but also reduce the manufacturing cost [

115]. However, the methyl group does not play an effective role in improving the compressive strength of silica aerogel. Yang et al. fabricated silica aerogel using MTMS and VTES as precursor and demonstrated that the replacement of methyl with vinyl groups enhances the mechanical properties (compressive stress 0.57 MPa) [

116]. In addition, including propyl groups in the underlying silica skeleton of MTMS-derived aerogels can also improve their flexibility such that they can be compressed to 70% of their original height [

117]. Recently, Smitha et al. fabricated hydrophobic aerogel coating made from a composite of MTMS and GPTMS (1:0.5) and demonstrated oil adsorption properties [

118]. The authors also prepared low density porous silica aerogel by varying the molar ratio of TEOS/GPTMS through ambient pressure drying [

119]. Recently,

Hüsing and coworkers prepared flexible aerogels with reactive functional groups by co-condensing MTMS with various organosilanes (VTMS, CPTMs, MPTMS, TMSPMA) with the aid of CTAB surfactant [120]. The ratio of MTMS and organosilane was kept above 8.5:1.5 to retain their interesting properties. The resulting functional gels exhibited excellent elastic compression behavior up to 60%. They observed that density, porosity, and linear shrinkage remained the same with the increasing the size of functional groups, whereas surface area decreased with further modification of gels.Silica aerogels with more flexibility have been fabricated using methyltriethoxysilane (MTES) as a sole precursor. Nadargi and coworkers prepared monolithic aerogels by employing a two-stage acid-base catalyzed sol-gel process followed by supercritical drying. Aerogels with different densities were obtained by varying the molar ratio of MeOH/MTES(S) [

121,

122]. It was observed that low dilution of MTES led to less flexibility, and the aerogels with the highest S ratio showed the highest flexibility. However, further bending of these samples resulted in crack formation. Furthermore, Aravind et al. synthesized porous hydrophobic MTES-based silica aerogel under ambient pressure drying with a surface area of 727 m

2/g [

123]. However, the Young’s modulus and shrinkage were not mentioned. Cui and coworker studied the temperature-dependent microstructure of silica aerogels using 0.5 molar ratios of MTES/TEOS. Aerogels were subject to heat at different temperatures (200–500 °C for 2 h). They found temperature-driven transition from hydrophobic to partially hydrophilic to completely hydrophilic [

124]. Transparent flexible silica aerogels are prepared by replacing the traditional solvent (alcohol) with water, using MTES and CTAB, via an acid-base two-step method [

125]. The resulting flexible, transparent, hydrophobic (151°) silica aerogels exhibited low thermal conductivity (0.0215 W/mK) with an initial decomposition temperature of up to 511 °C.

Alternatively, organotrialkoxysilanes with longer alkyl groups (ethyl, vinyl, and propyl) are used to prepare aerogels. Itagaki et al. have investigated the phase separation behavior by varying the molar ratio of VTMS and TMOS as co-precursors in the presence of formamide under an acidic condition and prepared monolithic amorphous alkylsiloxane gels with well-defined macropores [

126]. Shimizu et al. developed transparent hydrophobic polyethylsilsesquioxane (PESQ) and polyvinylsilsesquioxane (PVSQ) aerogel using ETMS and VTMS precursors in the presence of nonionic surfactant EH-208 (polyoxyethylene 2-ethylhexyl ether) [

127]. Micrographs clearly show a thick gel skeleton with large pores (100 nm), and the presence of a coarsened porous structure causes visible-light scattering.

Trifunctional precursors with long alkyl chains are also employed to prepare silica aerogels. Yang et al. fabricated superhydrophobic silica aerogel by incorporating PTES/TEOS co-precursors employing ambient pressure drying [

128]. The resulting aerogels exhibited low density, high surface area, and can endure up to 70% maximum linear compression with few cracks. They also possess a high absorption capacity (8–10 times their own weight). Recently, Li and coworkers prepared

silica-polymethylmethacrylate composite

aerogel using TMOS and TMSPMA via load transfer across a static electric phase interface [

62]. Rao et al. used monofunctional silica precursor trimethylethoxysilane (TMES) with TMOS to prepare hydrophobic silica aerogels [

129]. TMES/TMOS molar ratio (S) was varied from 0 to 2.35. As the S value increased, the hydrophobicity of the aerogels increased, but the optical transmission diminished from 93% to less than 5% in the visible range.

Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) is also used to construct novel organic–inorganic materials. Many research groups have developed unique silica aerogels based on POSS which have resulted in some inspiring improvements to aerogel properties [

130,

131,

132]. Jana et al. evaluated a POSS molecule carrying phenyl, iso-butyl, and cyclohexyl organic side groups as a multifunctional reinforcing agent within the silica aerogel [

133]. The compressive modulus increased six-fold with less than 5 wt% trisilanol phenyl-POSS, with negligible increases in density. Recently, Li and coworkers prepared octa [2-((3-(trimethoxysilyl)- propyl)thio)ethyl]silsesquioxane (OTS)-based superhydrophobic aerogels using MPTMS and POSS via thiol-ene click chemistry and studied the effects of OTS:H

2O molar ratio on the physical properties of aerogels [

134]. Benefiting from the alternating rigid inorganic nanocage skeleton, the resulting flexible OTS aerogels had high surface area (542–834 m

2/g) and high compression strengths (4.96–6.48 MPa), with a better compression modulus (18.79–25.84 MPa). The good oil–water separation efficiency of OTS aerogels can be utilized for practical application.

Silica aerogels are made using monomeric or polymeric precursors through bimodal or spinodal decomposition phase separation. Kanamori et al. prepared a series of materials using pre-polymerized precursor before gelation [

135]. They concluded that using pre-polymerized precursor significantly improves the thermal and mechanical properties of resulting aerogels. As a follow-up to this, a new class of transparent, superflexible silica-based aerogels has been prepared using pre-polymerized silica precursor prior to gelation. This novel approach was first introduced by Zu et al. They initially polymerized monofunctional (VDMMS), bifunctional (VMDMS, VMDES, and AMDMS), and trifunctional (VTMS, ATMS) precursors and later cross-linked the network with siloxane bonds to form a polymeric backbone in the presence of a di-tert-butyl peroxide (DTBP) initiator via ambient pressure drying [

136,

137,

138]. The resulting aerogel network consisted of polysiloxane as cross-linker and hydrocarbon chain as the backbone, which led to excellent flexibility and processability while maintaining the superinsulating properties (15.2 mW/mK). This double-cross-linking approach significantly enhanced the skeletal structure of aerogels to resist cracking during the drying process. This method is low-cost and is scalable from molecular level to robust networks, and the aerogels exhibit hydrophobicity [

139]. However, this strategy requires higher temperatures and a prolonged aging process.

Polyvinylpolymethylsiloxane (PVPMSA) aerogels were reported by Feng et al. using a DTBP initiator and following Zu’s double-cross-linking approach, and they systematically studied the effect of temperature and pressure on the thermal properties [

140]. They concluded that the thermal conductivity of PVPMSA aerogels is greatly affected by the temperature. Polyvinylmethyldimethoxysilane (PVMDMS)-reinforced MTMS aerogels were also developed, which showed elastic recovery properties and super high surface area (1479 m

2/g), mainly due to the long aliphatic hydrocarbon chain and the presence of excess methyl groups [

141]. Furthermore, Park et al. used pre-polymerized VTMS and GPTMS precursors to create a nonparticulate structure through spinodal decomposition phase separation [

142,

143]. This approach reduced the aging process and offered aerogels with enhanced mechanical properties.

All data support the notion that alkyltrialkoxysilane-based aerogels have huge potential for commercialization as they possess desirable properties such as flexibility, hydrophobicity, and good mechanical properties. The nature of flexible alkyltrialkoxysilanes offers additional advantages, but they also come with a higher price tag. Therefore, they are still not ready for large-scale fabrication. Although incorporating ORMOSILs in the silica backbone performed well with regard to increasing the mechanical strength, this property was only improved to a limited extent and further mechanical reinforcement is still required.

3.2. Bridged Polysilsesquioxanes

Bridged polysilsesquioxane (BPS) is a class of highly cross-linked organic–inorganic hybrid materials prepared from molecular precursors ((R’O)

3Si-R-Si(OR’)

3, where R is typically alkyl or aryl) [

144]. These precursors contain variable organic bridging groups attached to two or more trifunctional silyl groups. The bridging group allows the synthesis of final materials with tunable physical, chemical, and mechanical properties [

145]. BPS networks (O

1.

5Si-R-SiO

1.

5)

n with periodic mesopores are known as periodic mesoporous organosilicas (PMOs) [

146,

147,

148]. The organic linkers will increase separation between Si atoms and further decrease cross-linking density. BPS aerogels exhibit distinct properties such as high flexibility, light weight, and low thermal conductivity. Therefore, they are used as adsorbents for cleaning up organic contaminants [

149], catalyst supports [

150], low dielectrics materials [

151], etc. However, in recent decades, BPS has been reported with different applications ranging from catalyst to drug delivery. Loy and Shea have extensively explored BPS using aliphatic and aromatic bridging groups in order to tailor the physical properties of the resulting aerogels [

152,

153,

154,

155]. These studies focused on porosity, relative surface area, and reactivity of the precursor.

Loy and coworkers prepared alkylene-bridged polysilsesquioxane using various bis(triethoxysilyl) alkanes and studied the effect of catalysts and the length of alkylene bridging group [

156,

157]. They concluded that base-catalyzed materials had higher degrees of condensation and were more hydrophobic than those prepared under acidic conditions. Among typical alkoxysilanes 1,6-bis(trimethoxysilyl)hexane (BTMSH) with a relatively long and flexible bridging group was an attractive candidate that imparted flexibility to the polysiloxane-based network [

158]. Preparations of hexylene-bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels and xerogels with a high degree of condensation and low bulk density were reported [

159,

160]. The resulting opaque aerogels exhibited improved flexural strength.

For many applications, it is desirable to have flexible materials. Aoki et al. introduced hexylene-bridged polysilsesquioxane to prepare flexible, transparent aerogels from BTMSH in dimethylformamide (DMF) solution followed by SCF drying [

161]. The DMF solvent prevents phase separation of BTMSH-derived condensates in the course of gelation. Although the resulting aerogels showed good flexibility, an insufficient spring-back behavior upon compression was observed, which can be attributed to the remaining silanol groups on the pore surface. Surface modification with HMDZ was performed to minimize the residual silanol groups. The resulting gels dried under ambient pressure exhibited high transparency (71% transmission) with low density (0.13 g/cm

3). Meador et al. explored porous, hydrophobic aerogels using a mixture of bis [3-(triethoxysilyl)propyl]disulfide (BTSPD), TMOS, and VTMS. Aerogels prepared using the optimum BTSPD concentration provided excellent elastic recovery at all TMOS concentrations [

162]. The soft disulfide segments, which act as an organic spacer, endow the aerogels with excellent elasticity, which recovers nearly completely after a compression of 75%.

Wang et al. produced soft and durable aerogels from bridged precursors containing C–S bonds using MPTMS and VTMS precursors

by employing UV-initiated thiol-ene click reaction [

163,

164]. The alkoxy groups of the precursor influence the performance of aerogels and the flexible thioether bridge contributes to robustness. Recently, Guo and coworkers demonstrated highly flexible BSAs by introducing C–O and C–S bonds into the molecular chain using VTES and 2,2′-(ethylenedioxy)-diethanethiol (EDDET) as co-precursors followed by ambient pressure drying [

165]. The BSA aerogels were easily compressed and recovered their original shape. Furthermore, the aerogels retained their integrity even after bending at 180

o. In addition, these materials showed excellent repeatable absorption for organic liquids.

To investigate the relationship between catalytic method and properties of aerogels, Wang and coworkers fabricated amine-bridged polymethylsiloxane using APTMS and 3-(2,3-epoxypropoxy) propyltrimethoxysilane (EPTMS) precursor based on reactions between epoxy and amine groups [

166]. The BSQ aerogels obtained exhibited low density (0.22 g/cm

3) and high compression modulus (20.4 MPa). Recently, molecular bridged silica aerogels (MBSAs) were prepared to study the influence of catalysts using

N,

N-bis(propyltriethoxysilyl)carbamide (bPTSCA), which was synthesized from APTES and 3-isocyanatopropyltriethoxysilane (IPTES) using different catalysts (HCl, NH

4OH, and NH

4F) [

167]. They observed that urethane-bridged silica aerogels showed adjustable mechanical properties ranging from rigid to elastic by varying their density. To improve the thermal stability of BSA, it was necessary to introduce thermally stable groups as bridging groups. In this regard, Zou et al. developed thiourethane-bridged polysilsesquioxanes from MPTMS via triethylamine initiated thiol-isocyanate reaction, the sulfur analog of urethane with exceptional elastic properties [

168]. Three types of diisocyanates were used to investigate the influence of the rigidity of the bridging groups. The resulting aerogels exhibited low density, low thermal conductivity, and good mechanical properties to withstand 50% deformation under compression.

In another report, Schaefer et al. evaluated arylene-bridged polymethylsiloxane by inserting organic rigid-rod spacers at regular intervals into the silicate network, which formed an integral part of the chemical connectivity of the material [

171]. They obtained highly porous aerogels with high surface areas (1880 m

2/g) benefiting from the rigid arylene bridge. Aromatic containing bridges are stiffer, but provide excellent control over pore size and the distribution of pores. Because of the stiff bridge, the phenylene-bridged BSQ synthesized by Boday et al. had a flexural strength of 0.048 MPa, which is stronger than that of hexylene-bridged aerogels and 30% stronger than that of silica aerogels of the same density [

159].

Molecular-bridged silica aerogels (MBSA) are good candidates for oil–water separation. MBSAs were synthesized based on the catalyst-free bridging of APTES and terephthalaldehyde (TPAL) via Schiff base condensation through a one-pot autocatalytic approach [

174]. The aerogels obtained exhibited good mechanical properties with 90% deformation and high absorption capability (11–24 times their own weight). Recently, Chen et al. developed a facile method to prepare MBSAs using TPAL, APTES, and MTMS co-precursors in the presence of acetic acid as catalyst followed by vacuum during. The resulting monolithic aerogels exhibited low density and excellent flexibility, with a Young’s modulus of 0.029 MPa [

175]. They also showed good absorption for different organic liquids. To further study the influence of precursor and solvent, Chen and coworkers synthesized two types of aerogels by reacting m-phthalaldehyde (MPA) with APTES and APDEMS dried at ambient pressure [

176]. MPA/APTE-based aerogels were hydrophilic with small particle sizes. In contrast, MPA/APDEMS-based aerogels were hydrophobic with large particle sizes and thick networks due to the presence of methyl groups and slow reaction rates. Recently, Tang et al. prepared bismaleimide-bridged silsesquioxane (BMIT-BSA) by utilizing MPTES and (4,4′-diphenylmethylene)bismaleimide (BMI) via thiol-maleimide click reaction followed by vacuum drying [

177]. The aerogels obtained showed excellent heat resistance (0.044 W/mK), were superhydrophobic, light-weight, and had enhanced thermal stability (336 °C).

Incorporating flexible, organic linking groups into the silica backbone has been shown to be a versatile way to improve the elastic properties of aerogels. The aerogels can recover from compression up to as much as 50% strain and are flexible in some cases. The flexible linking groups also result in greater hydrophobicity and provide a means to tailor pore structure. Use of flexible polymer-cross-linked aerogels is a promising route to making robust aerogel monoliths, thin films, and sheets, enabling a multitude of aerospace applications.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nano13091498