The impact of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic is still being rfevealedlt, and little is known about the effect of COVID-19-inducedimpact on hospital operations of the loss of outpatients and inpatient losses on hospital operations in s due to COVID-19 in many counties. Hence, we aimed to exploreTherefore exploring whether hospitals ahave adopted profit -compensation activities after the 2020 first-following the first wave outbreak of f the COVID-19 outbreak in China. A total of 2,616,589 hospitalization in 2020. 2616589 inpatient records fromor 2018, 2019, and 2020 were extracted from 36 tertiary hospitals in a western province in China; we applied a; a difference-in-differences event study design was used to estimate the dynamic effeimpact of COVID-19 on hospitalized total inpatients’ total expenses costs before and after the last confirmed case. We fouAnd that average increase in mean total expenses for each costs per patient increased by 8.7% to of between 8.7% and 16.7% can be found in the first 25 weeks after the city reopened and hospital admissions urban reopening and returned to normal. Our findings emphasize that the increase in total inpatient expenses was mainly covered by claiming expenses from health insurance and was largely driven by an increase in the expenses for laboratory tests and medical consumables. Our study documents that there were hospitalization. It indicates that hospitals experienced profit compensationng activities in hospitals ay after the 2020 first-first wave of the outbreak of COVID-19 in China, which was in 2020, driven by the loss ofreduction in hospitalization admissions during this wave outbreakat wave.

- profit compensation activities

- COVID-19

- hospital

1. Introduction

2. Brief Introduction to China’s Healthcare Delivery System

China’s healthcare delivery system is a complex network of public and private providers, governed by policies and regulations aimed at ensuring access to basic health services for its large and diverse population. China has a three-tiered system for healthcare delivery: health organizations and providers operate at county, township, and village levels in rural areas, and at municipal, district, and community levels in urban areas [28][27]. Primary care services are provided at community health centers and township healthcare centers, secondary care is provided by district and county hospitals, and tertiary care is provided by large specialty and general hospitals in major cities. Public hospitals are owned and operated by the government, and are organized into tiers according to their level of service. They are typically the largest and most well-funded providers, with strong links to medical education and research institutions. Public hospitals dominate the market for specialized and tertiary care, and employ 64% of practicing physicians, handle 82% of inpatients and 40% of outpatients, and account for about half of China’s total healthcare spending [29][28]. Private hospitals, on the other hand, are owned and operated by nongovernmental entities or individuals. They are generally smaller and provide more specialized services than public hospitals, such as cosmetic and reproductive medicine. Historically, private hospitals have been less regulated than their public counterparts, but recent reforms have sought to improve their quality and increase their role in the healthcare delivery system. The private sector has experienced a vast expansion in China’s hospital market in the past decades for both healthcare supply capacity and delivered care [30][29], but the public health sector is the main healthcare provider [28][27].3. Compensation Mechanism of Chinese Public Hospitals and Its Potential Influence by COVID-19

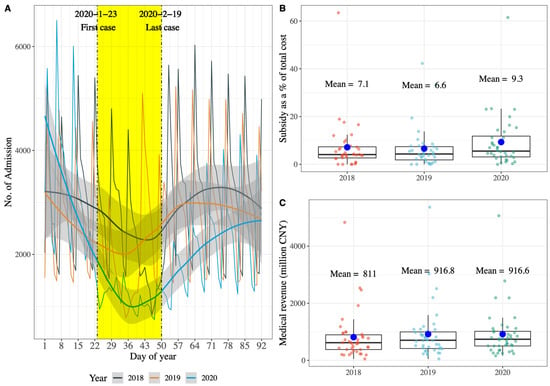

Public hospitals in China have been mainly compensated by service charges, drug sales, and government budget allocations in the past decades. However, since 2012, the compensation mechanism of Chinese public hospitals has undergone a relatively large reform, starting with county-level public hospitals and extending to municipal-level public hospitals in 2016. This round reform focused on four interrelated areas: removing the drug mark-up, increased budget allocation, adjustments of fee schedules, and reforming payment methods [29][28], as a consequence that public hospitals revenue from service charges and government budget allocations only. Moreover, removing the up to 15% markup for drug sales from public hospitals in China brought about a reduction in drug expenditures expected by the policymakers [31[30][31][32][33][34][35],32,33,34,35,36], however, an increase in expenditures for diagnostic tests or medical consumables and hospitalization was observed from different aspects [31[30][31][32][34],32,33,35], which was not expected by the policymakers, and government subsidies to public hospitals increased slightly by 2–5% in the 2 to 6 years after the policy was implemented [36][35]. All this evidence suggests that China’s public hospitals rely heavily on medical service charges to sustain their operations and development. As mentioned, hospitals in many countries experienced an admission loss during the first encounter with COVID-19 in 2020; It also can be observed a significant admission loss of tertiary hospitals, in line with other studies (Figure 1A) [14,16][14][16]. In addition, it can be found that public hospitals of these tertiary hospitals in China received more subsidies for the loss of service charges caused by the admission loss; government subsidies as a percentage of total costs increased from 6.6% in 2019 to 9.3% in 2020 (Figure 1B), however, it is complicated because medical revenue of tertiary hospitals did not decrease between 2019 and 2020 (Figure 1C). Therefore, it can be hypothesized that tertiary hospitals in China have profit compensation motive and activities when observing that the admission count returned to normal after strict measures were relaxed.

References

- Shen, H.; Fu, M.; Pan, H.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Firm Performance. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 56, 2213–2230.

- Tisdell, C.A. Economic, Social and Political Issues Raised by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Econ. Anal. Policy 2020, 68, 17–28.

- Severo, E.A.; De Guimarães, J.C.F.; Dellarmelin, M.L. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Environmental Awareness, Sustainable Consumption and Social Responsibility: Evidence from Generations in Brazil and Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 124947.

- Shang, W.-L.; Chen, J.; Bi, H.; Sui, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H. Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic on User Behaviors and Environmental Benefits of Bike Sharing: A Big-Data Analysis. Appl. Energy 2021, 285, 116429.

- So, M.K.P.; Chu, A.M.Y.; Chan, T.W.C. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Financial Market Connectedness. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 38, 101864.

- Sun, X.; Wandelt, S.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, A. COVID-19 Pandemic and Air Transportation: Successfully Navigating the Paper Hurricane. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102062.

- Mafham, M.M. COVID-19 Pandemic and Admission Rates for and Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in England. Lancet 2020, 396, 381–389.

- Palmer, K.; Monaco, A.; Kivipelto, M.; Onder, G.; Maggi, S.; Michel, J.-P.; Prieto, R.; Sykara, G.; Donde, S. The Potential Long-Term Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Patients with Non-Communicable Diseases in Europe: Consequences for Healthy Ageing. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1189–1194.

- Bodilsen, J.; Nielsen, P.B.; Søgaard, M.; Dalager-Pedersen, M.; Speiser, L.O.Z.; Yndigegn, T.; Nielsen, H.; Larsen, T.B.; Skjøth, F. Hospital Admission and Mortality Rates for Non-Covid Diseases in Denmark during Covid-19 Pandemic: Nationwide Population Based Cohort Study. BMJ 2021, 373, n1135.

- Caminiti, C.; Maglietta, G.; Meschi, T.; Ticinesi, A.; Silva, M.; Sverzellati, N. Effects of the COVID-19 Epidemic on Hospital Admissions for Non-Communicable Diseases in a Large Italian University-Hospital: A Descriptive Case-Series Study. JCM 2021, 10, 880.

- Kalanj, K.; Marshall, R.; Karol, K.; Tiljak, M.K.; Orešković, S. The Impact of COVID-19 on Hospital Admissions in Croatia. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 720948.

- Santi, L.; Golinelli, D.; Tampieri, A.; Farina, G.; Greco, M.; Rosa, S.; Beleffi, M.; Biavati, B.; Campinoti, F.; Guerrini, S.; et al. Non-COVID-19 Patients in Times of Pandemic: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Cause-Specific Mortality in Northern Italy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248995.

- Domingo, L.; Comas, M.; Jansana, A.; Louro, J.; Tizón-Marcos, H.; Cos, M.L.; Roquer, J.; Chillarón, J.J.; Cirera, I.; Pascual-Guàrdia, S.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on Hospital Admissions and Healthcare Quality Indicators in Non-COVID Patients: A Retrospective Study of the First COVID-19 Year in a University Hospital in Spain. JCM 2022, 11, 1752.

- Yang, Z.; Wu, M.; Lu, J.; Li, T.; Shen, P.; Tang, M.; Jin, M.; Lin, H.-B.; Shui, L.; Chen, K.; et al. Effect of COVID-19 on Hospital Visits in Ningbo, China: An Interrupted Time-Series Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2021, 33, mzab078.

- Cai, Y.; Kwek, S.; Tang, S.S.L.; Saffari, S.E.; Lum, E.; Yoon, S.; Ansah, J.P.; Matchar, D.B.; Kwa, A.L.; Ang, K.A.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on a Tertiary Care Public Hospital in Singapore: Resources and Economic Costs. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 121, 1–8.

- Xiao, H.; Dai, X.; Wagenaar, B.H.; Liu, F.; Augusto, O.; Guo, Y.; Unger, J.M. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Services Utilization in China: Time-Series Analyses for 2016-2020. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2021, 9, 10.

- Birkmeyer, J.D.; Barnato, A.; Birkmeyer, N.; Bessler, R.; Skinner, J. The Impact Of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Hospital Admissions In The United States: Study Examines Trends in US Hospital Admissions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 2010–2017.

- Boserup, B.; McKenney, M.; Elkbuli, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Emergency Department Visits and Patient Safety in the United States. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 1732–1736.

- Jeffery, M.M.; D’Onofrio, G.; Paek, H.; Platts-Mills, T.F.; Soares, W.E.; Hoppe, J.A.; Genes, N.; Nath, B.; Melnick, E.R. Trends in Emergency Department Visits and Hospital Admissions in Health Care Systems in 5 States in the First Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 1328.

- Cantor, J.; Sood, N.; Bravata, D.M.; Pera, M.; Whaley, C. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Policy Response on Health Care Utilization: Evidence from County-Level Medical Claims and Cellphone Data. J. Health Econ. 2022, 82, 102581.

- McIntosh, A.; Bachmann, M.; Siedner, M.J.; Gareta, D.; Seeley, J.; Herbst, K. Effect of COVID-19 Lockdown on Hospital Admissions and Mortality in Rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Interrupted Time Series Analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047961.

- Sevalie, S.; Youkee, D.; van Duinen, A.J.; Bailey, E.; Bangura, T.; Mangipudi, S.; Mansaray, E.; Odland, M.L.; Parmar, D.; Samura, S.; et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Hospital Utilisation in Sierra Leone. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e005988.

- Yuan, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Dai, Z.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y. Modelling the Effects of Wuhan’s Lockdown during COVID-19, China. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 484–494.

- Meng, X.; Guo, M.; Gao, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Kang, L. The Effects of Wuhan Highway Lockdown Measures on the Spread of COVID-19 in China. Transp. Policy 2022, 117, 169–180.

- Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, P.; Qi, J.; Wang, L.; Pan, J.; You, J.; Yang, J.; et al. Excess Mortality in Wuhan City and Other Parts of China during the Three Months of the COVID-19 Outbreak: Findings from Nationwide Mortality Registries. BMJ 2021, 372, n415.

- Qiu, Y.; Chen, X.; Shi, W. Impacts of Social and Economic Factors on the Transmission of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J. Popul. Econ. 2020, 33, 1127–1172.

- Meng, Q.; Mills, A.; Wang, L.; Han, Q. What Can We Learn from China’s Health System Reform? BMJ 2019, 365, l2349.

- Xu, J.; Jian, W.; Zhu, K.; Kwon, S.; Fang, H. Reforming Public Hospital Financing in China: Progress and Challenges. BMJ 2019, 365, l4015.

- Deng, C.; Li, X.; Pan, J. Private Hospital Expansion in China: A Global Perspective. Glob. Health J. 2018, 2, 33–46.

- Yi, H.; Miller, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Rozelle, S. Intended And Unintended Consequences of China’s Zero Markup Drug Policy. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1391–1398.

- Yang, C.; Shen, Q.; Cai, W.; Zhu, W.; Li, Z.; Wu, L.; Fang, Y. Impact of the Zero-Markup Drug Policy on Hospitalisation Expenditure in Western Rural China: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 180–186.

- Fu, H.; Li, L.; Yip, W. Intended and Unintended Impacts of Price Changes for Drugs and Medical Services: Evidence from China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 211, 114–122.

- Shi, X.; Zhu, D.; Man, X.; Wang, W.; Zhu, K.; Nicholas, S.; He, P. “The Biggest Reform to China’s Health System”: Did the Zero-Markup Drug Policy Achieve Its Goal at Traditional Chinese Medicines County Hospitals? Health Policy Plan. 2019, 34, 483–491.

- Zeng, J.; Chen, X.; Fu, H.; Lu, M.; Jian, W. Short-Term and Long-Term Unintended Impacts of a Pilot Reform on Beijing’s Zero Markup Drug Policy: A Propensity Score-Matched Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 916.

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Impact of Zero-Mark-up Medicines Policy on Hospital Revenue Structure: A Panel Data Analysis of 136 Public Tertiary Hospitals in China, 2012–2020. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e007089.