Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jessie Wu and Version 3 by Jessie Wu.

Functional mitral regurgitation (FMR) and tricuspid regurgitation (FTR) occur due to cardiac remodeling in the presence of structurally normal valve apparatus. Two main mechanisms are involved, distinguishing an atrial functional form (when annulus dilatation is predominant) and a ventricular form (when ventricular remodeling and dysfunction predominate). Both affect the prognosis of patients with heart failure (HF) across the entire spectrum of left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF), including preserved (HFpEF), mildly reduced (HFmrEF), or reduced (HFrEF).

- heart failure

- mitral regurgitation

- tricuspid regurgitation

- atrial functional mitral regurgitation

1. Introduction

Functional (secondary) mitral (FMR) and tricuspid (FTR) valve regurgitation are shared across the entire spectrum of heart failure (HF) and negatively affect symptoms and prognosis [1][2]. They may occur isolated or concomitantly (bivalvular functional regurgitation), independent of the HF subgroup [3]. By definition, any functional regurgitation occurs due to cardiac remodeling and dysfunction and appears in a structurally normal valve apparatus [3][4][5][6][7]. Annular dilatation and impaired contraction cause atrial functional regurgitation. Restricted motion of the leaflets due to ventricular remodeling and dysfunction produces ventricular functional regurgitation. RWesearchers can diagnose FMR and FTR in any HF phenotype as defined by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): preserved (HFpEF), mildly reduced (HFmrEF), or reduced (HFrEF). Proper and simultaneous recognition of the specific mechanism of regurgitation on the one hand (functional atrial, ventricular, or mixed) and the phenotype of HF on the other (HfrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF) is crucial for prognosis and therapy.

2. Epidemiology

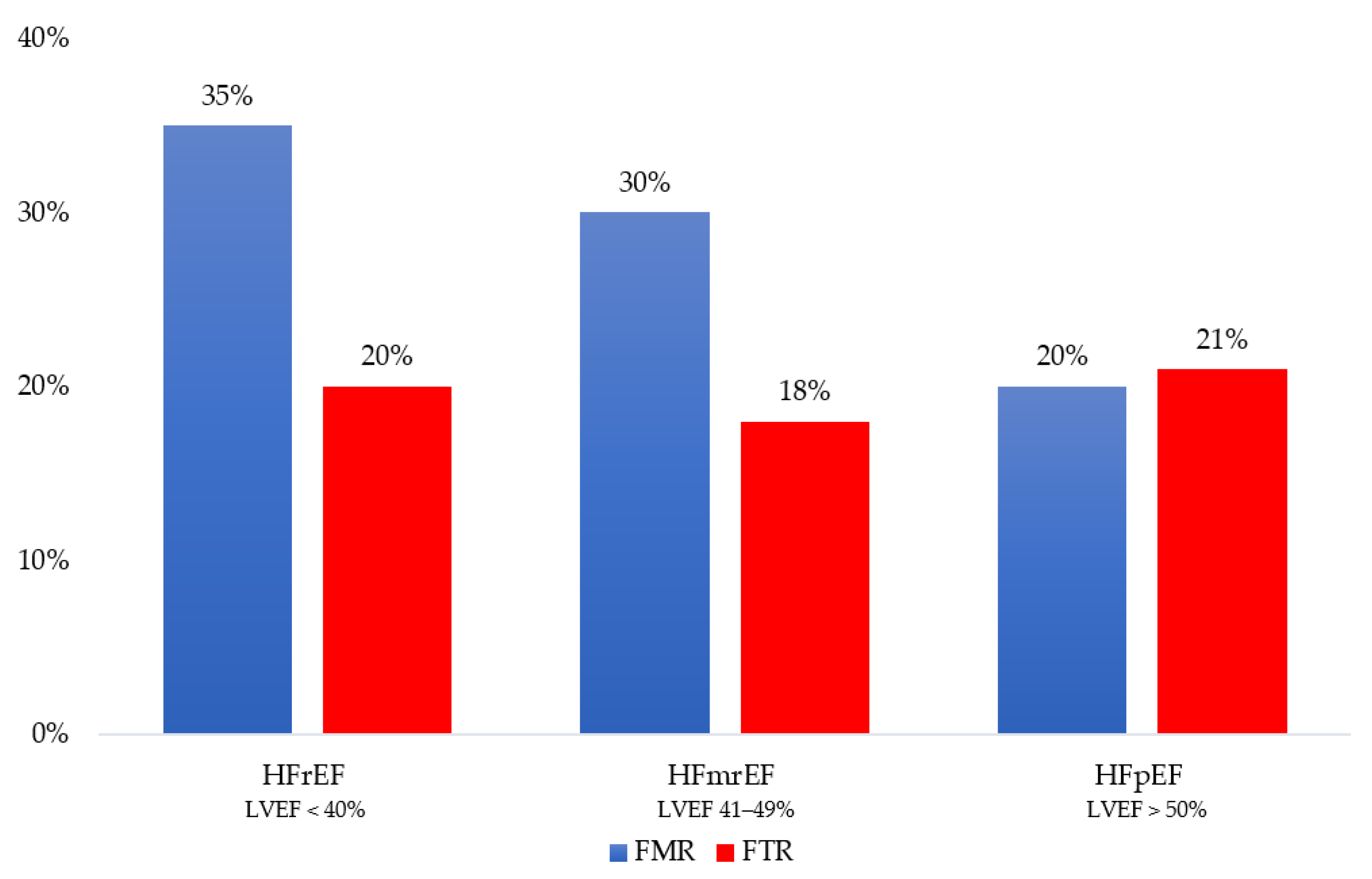

In HF, moderate or severe FMR affects up to 30% of patients, and it seems more frequent in HFrEF, followed by HFmrEF and HFpEF [2]. The prospective analysis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Heart Failure Long-Term Registry shows a prevalence of moderate-to-severe FMR approaching 35% in the HFrEF group, 30% in the HFmrEF group, and 20% in the HFpEF group (p < 0.001) (Figure 1) [8]. In advanced HFrEF (stage C–D), the prevalence of severe FMR can reach 45% [9][10][11][12]. There are no dedicated studies linking the prevalence of the specific mechanism causing FMR (atrial vs. ventricular) to the single HF phenotypes (HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF). However, rwesearchers can hypothesize that in HFrEF, ventricular mechanisms are likely to prevail, but atrial mechanisms can coexist and are proportional to the disease severity. Moving from HFrEF to HFmrEF and HFpEF, the ventricular mechanisms become less relevant, leaving atrial mechanisms the primary determinants of FMR.

Figure 1. Distribution of functional mitral regurgitation (FMR) and functional tricuspid regurgitation (FTR) across the heart failure phenotype as defined by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): reduced (HFrEF), mildly reduced (HFmrEF) and preserved (HFpEF).

3. Pathophysiology and Prognosis

Two main mechanisms are responsible for functional mitral and tricuspid regurgitation: (1) the annular dilation and/or loss of annular contraction, through a condition of atrial remodeling (atrial functional); (2) restricted leaflets motion due to ventricular remodeling, which implies papillary muscle displacement, causing chordal tethering (ventricular functional). These geometrical alterations and functional impairments occur in the presence of a structurally normal valve apparatus.

Ventricular FMR typically occurs in HFrEF due to ischemic or non-ischemic ventricular disease. According to the general classification, the presence of coronary artery disease affecting LV geometry and function allows for differentiation between ischemic and non-ischemic FMR. Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), regardless of its etiology, often leads to secondary MR, due to the changes in LV shape (increase in LV sphericity and enlargement in LV diameters). DCM recognizes genetic, but also acquired causes. Monogenic diseases, syndromic forms, and neuromuscular diseases are described among genetic forms. Drugs, toxins, and nutritional deficiencies can lead to acquired forms of DCM with FMR.

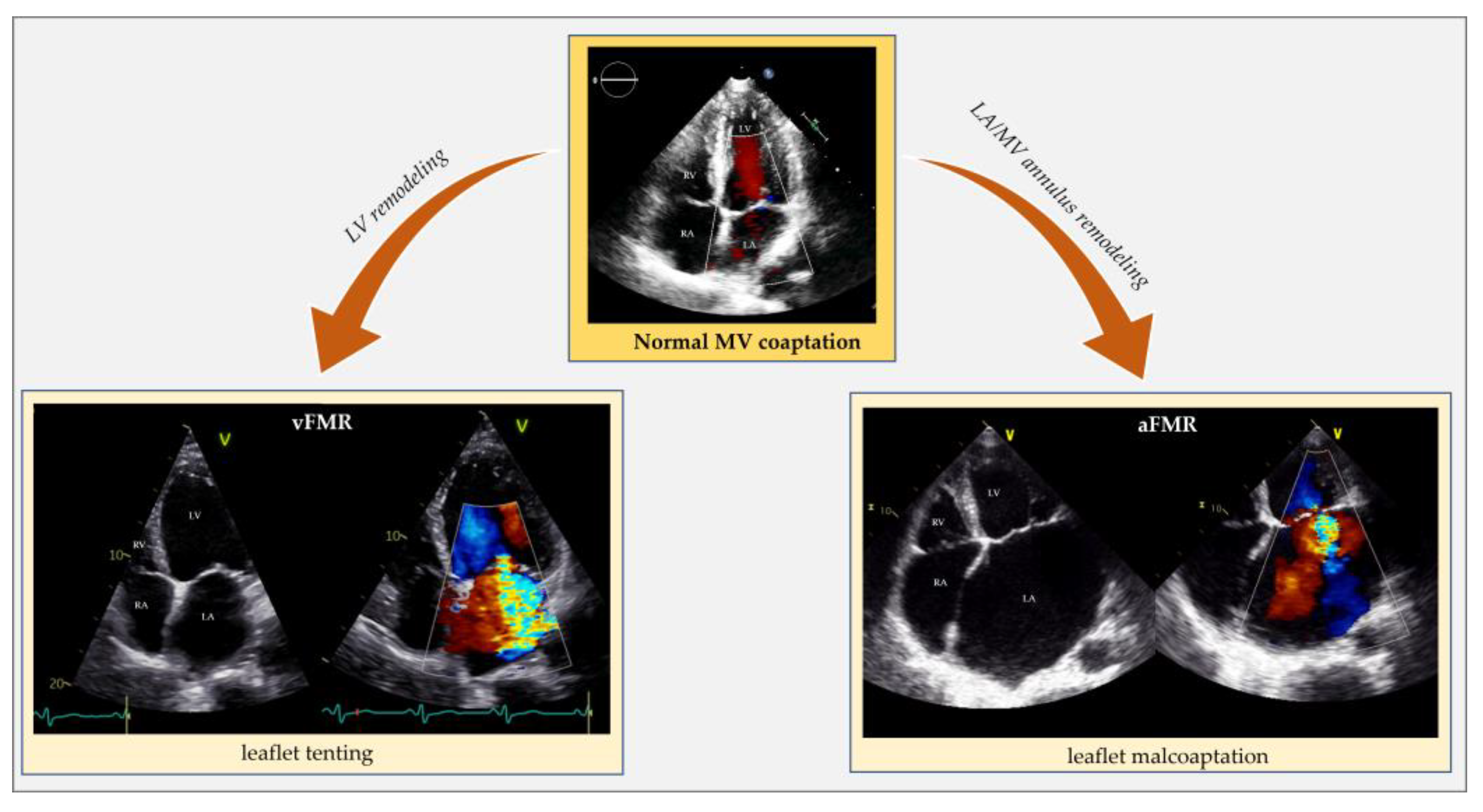

The mechanism of FMR is valve tenting (a more apical position of the leaflets and their coaptation point during the systolic phase) (Figure 2). Specifically, valve tenting results from an imbalance between tethering and closing forces. In ventricular FMR, tethering forces increase (due to LV remodeling), and closing forces decrease (due to reduced contractility and dyssynchrony) [20][21]. Valve tenting can be symmetric or asymmetric. While symmetric tenting occurs more often in global ventricular remodeling, asymmetric tenting usually occurs if the tethering forces predominate on the posterior mitral valve leaflet. FMR negatively impacts survival, either in HFpEF [adjusted hazard ratio (adj. HR) 1.40, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09–1.81; p = 0.009] [22], HFmrEF (adj. HR 1.72, 95% CI 1.24–2.39; p = 0.0012) [8] and HFrEF (adj. HR 1.61, 95% CI 1.22–2.12; p = 0.001] [2]. In HFrEF, small amounts of FMR increase short- and long-term mortality. Particularly, there is an exponential mortality increase for any effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA) increment above a threshold of 0.10 cm2 when compared with degenerative MR [23].

Figure 2. Echocardiographic comparison of normal mitral valve coaptation and functional mitral regurgitation in the context of left ventricle remodeling and dysfunction (vFMR) opposed to left atrial and annular dilatation (aFMR). aFMR: atrial functional mitral regurgitation; LA: left atrium; LV: left ventricle; MV: mitral valve; RA: right atrium; RV: right ventricle; vFMR: ventricular functional mitral regurgitation.

Atrial FMR is common in AFib but also occurs in sinus rhythm. HFpEF can generate atrial FMR by causing an increase in left atrium (LA) pressure and, eventually, LA remodeling without needing AFib to develop (Figure 2) [6][7][19][24][25].

Previously published data showed that not all patients with significant aFMR had known atrial arrhythmias. Dziadzko V. et al. found that 46% of patients with aFMR do not have atrial arrhythmias [24]. More recently, Mesi O. et al. demonstrated that 23% of the aFMR population had sinus rhythm [26]. This suggests that diastolic dysfunction with resultant atrial dilation and annular remodeling could be sufficient in promoting the genesis of mitral regurgitation. Nevertheless, AFib, HFpEF, and atrial FMR often coexist and negatively interact since they share most pathophysiological mechanisms [26][27][28][29][30][31]. AFib, causing LA remodeling, impaired atrial function, and atrial fibrosis, may negatively contribute to HFpEF and atrial FMR [28][29][30][31][32]. HFpEF, through diastolic dysfunction and increased LA pressures, systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, plays a crucial role in causing LA anatomical, mechanical and electrical remodeling favoring AFib and, consequently, atrial FMR. Once established, FMR negatively contributes to AFib and HFpEF progression.

In a Dziadzko V et al. study, patients with aFMR were significantly older than those with vFMR (80 ± 10 vs. 73 ± 14 years), translating into a different distribution of causes by age group [24]. The aFMR patients suffered mainly from atrial fibrillation/flutter (54% vs. 28%) and hypertension (81% vs. 69%). In contrast, vFMR patients were predominantly male (59% vs. 33%) with a prevalent history of myocardial infarction (17% vs. 9%) [24]. In addition, patients with ventricular FMR had the most significant LV remodeling, highest pulmonary pressure and lowest LVEF, stroke volume, and E/e’. Patients with atrial FMR presented smaller LV size, generally normal LVEF and stroke volume, with a modest MR volume and orifice, while E/e’ and pulmonary pressure were elevated [24]. In advanced LA and LV remodeling, a net distinction between the atrial and ventricular mechanism is no longer possible because these entities usually coexist. In HFmrEF, the volume overload caused by atrial FMR promotes the transition to HFrEF (and eventually to ventricular FMR) [18].

Even if current guidelines do not emphasize the need to discriminate the atrial from the ventricular mechanism in FMR, an early distinction is crucial to establish prognostic and therapeutic decisions [19]. The prognosis of ventricular FMR is significantly worse than atrial FMR, and each etiology leads to different treatments [24][33]. Though, the question remains whether the relationship between vFMR and mortality is direct or indirect, assuming that FMR is independently responsible for the outcomes and in all circumstances. On the one hand, a direct relationship between the degree of FMR and mortality has been widely described; on the other hand, several cohort publications stated that FMR was not independently responsible for the poor outcomes observed, suggesting that FMR is a surrogate for another cause of reduced survival [24][33][34]. In very advanced HFrEF, the underlying myocardial impairment and severity of LV dysfunction have a more negative impact on prognosis than FMR [18].

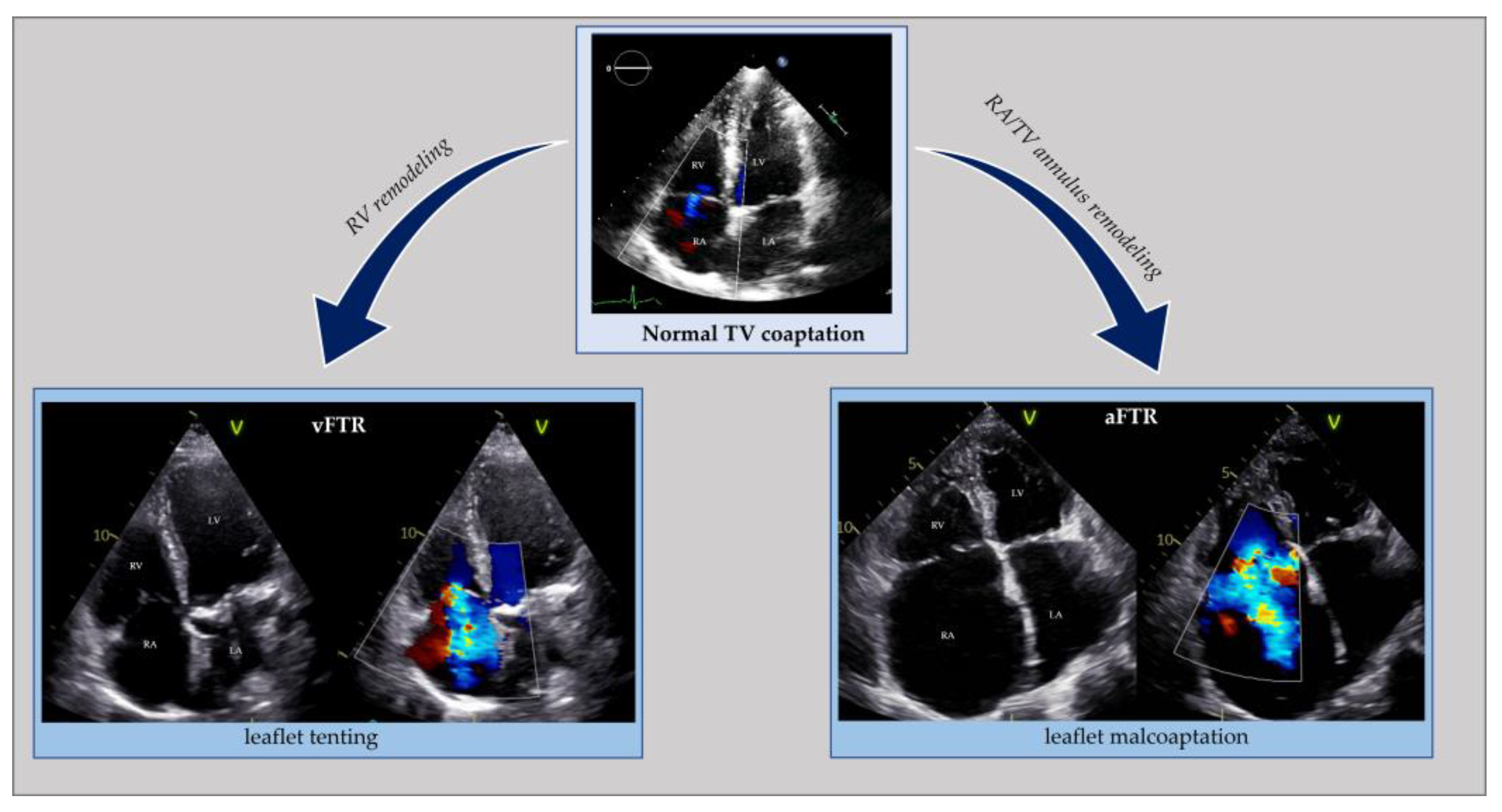

Similar to the left side of the heart, right ventricular remodeling, causing leaflet tethering and systolic restricted motion, is typical of vFTR. This can occur in case of left heart diseases (left ventricular dysfunction or left heart valve diseases) resulting in pulmonary hypertension, primary pulmonary hypertension, secondary pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction from any cause (e.g., myocardial diseases, ischemic heart disease, chronic right ventricular pacing). Atrial FTR develops due to tricuspid annular dilatation following right atrium (RA) remodeling, with the concomitant valve leaflets, right ventricle (RV), pulmonary circulation, and left side of the heart being macroscopically normal (Figure 3) [35][36][37][38]. In HFpEF, due to cardiac amyloidosis complicated by atrial FTR, an organic component usually coexists because of amyloid deposit infiltration in the leaflets [39][40].

Figure 3. Echocardiographic comparison of normal tricuspid valve coaptation and functional tricuspid regurgitation in the context of right ventricle remodeling (vFTR) opposed to right atrial and annular dilatation (aFTR). aFTR: atrial functional tricuspid regurgitation; LA: left atrium; LV: left ventricle; RA: right atrium; RV: right ventricle; vFTR: ventricular functional mitral regurgitation; TV: tricuspid valve.

A remarkable past medical history for AFib is widespread in atrial FTR. Atrial and ventricular FTR can coexist in simultaneous RA and RV remodeling. The same happens in FTR due to cardiovascular implantable electronic devices [37].

A stand-alone diagnosis of atrial FTR should make researcherus search for HFpEF [41]. The high prevalence of atrial FTR in HFpEF is consistent with shared risk factors such as renal dysfunction, aging, and AFib. AFib is also a primary determinant of atrial FTR. In HFrEF, the role of AFib in determining FTR diminishes. Compared to HFpEF, a lower percentage of patients with HFrEF have AFib [16][42][43]. In HFrEF, right ventricular remodeling and dysfunction are the main determinants of ventricular FTR.

Distinguishing between the atrial and ventricular FTR has prognostic and therapeutic implications [44][45][46]. The presence of FTR in the HF population significantly impairs prognosis, functional capacity, and quality of life and increases the risk of hospital admission. A strong association between FTR and mortality exists both in HFrEF (adj. HR 1.30, 95% CI 1.06–1.60; p = 0.014) [47] and HFpEF (adj. HR 2.87, 95% CI 1.61–5.09; p < 0.001) [48]. To our knowledge, dedicated studies on HFmrEF are missing, but the presence of FTR is proven to be an independent risk predictor of mortality in mixed cohorts of HFrEF and HFmrEF patients (adj. HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.39–1.78; p < 0.0001) [16][49]. Atrial FTR progresses rapidly but has a better outcome than ventricular FTR [37][50]. Additionally, while regurgitation severity is the only independent prognostic predictor in atrial FTR, RV function also predicts outcomes in ventricular FTR [16][50][51][52].

References

- Kadri, A.N.; Gajulapalli, R.D.; Sammour, Y.M.; Chahine, J.; Nusairat, L.; Gad, M.M.; Al-Khadra, Y.; Hernandez, A.V.; Rader, F.; Harb, S.C.; et al. Impact of Tricuspid Regurgitation in Patients with Heart Failure and Mitral Valve Disease from a Nationwide Cohort Study. Am. J. Cardiol. 2019, 124, 926–931.

- Goliasch, G.; Bartko, P.E.; Pavo, N.; Neuhold, S.; Wurm, R.; Mascherbauer, J.; Lang, I.M.; Strunk, G.; Hülsmann, M. Refining the prognostic impact of functional mitral regurgitation in chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 39–46.

- Bartko, P.E.; Arfsten, H.; Heitzinger, G.; Pavo, N.; Winter, M.-P.; Toma, A.; Strunk, G.; Hengstenberg, C.; Hülsmann, M.; Goliasch, G. Natural history of bivalvular functional regurgitation. Eur. Heart J.—Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 20, 565–573.

- Schlotter, F.; Dietz, M.F.; Stolz, L.; Kresoja, K.-P.; Besler, C.; Sannino, A.; Rommel, K.-P.; Unterhuber, M.; von Roeder, M.; Delgado, V.; et al. Atrial Functional Tricuspid Regurgitation: Novel Definition and Impact on Prognosis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 011958.

- Badano, L.P.; Muraru, D.; Enriquez-Sarano, M. Assessment of functional tricuspid regurgitation. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 1875–1885.

- Ennezat, P.V.; Maréchaux, S.; Pibarot, P.; Le Jemtel, T.H. Secondary Mitral Regurgitation in Heart Failure with Reduced or Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. Cardiology 2013, 125, 110–117.

- Hoit, B.D. Atrial Functional Mitral Regurgitation: The Left Atrium Gets its Due Respect. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 1482–1484.

- Chioncel, O.; Lainscak, M.; Seferovic, P.M.; Anker, S.D.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Harjola, V.-P.; Parissis, J.; Laroche, C.; Piepoli, M.F.; Fonseca, C.; et al. Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: An analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1574–1585.

- Bursi, F.; Barbieri, A.; Grigioni, F.; Reggianini, L.; Zanasi, V.; Leuzzi, C.; Ricci, C.; Piovaccari, G.; Branzi, A.; Modena, M.G. Prognostic implications of functional mitral regurgitation according to the severity of the underlying chronic heart failure: A long-term outcome study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2010, 12, 382–388.

- Patel, J.B.; Borgeson, D.D.; E Barnes, M.; Rihal, C.S.; Daly, R.C.; Redfield, M.M. Mitral regurgitation in patients with advanced systolic heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 2004, 10, 285–291.

- Grigioni, F.; Enriquez-Sarano, M.; Zehr, K.; Bailey, K.; Tajik, A. Ischemic mitral regurgitation. Long-term outcome and prognostic implications with quantitative Doppler assessment. Circulation 2001, 103, 1759–1764.

- Rossi, A.; Dini, F.L.; Faggiano, P.; Agricola, E.; Cicoira, M.; Frattini, S.; Simioniuc, A.; Gullace, M.; Ghio, S.; Enriquez-Sarano, M.; et al. Independent prognostic value of functional mitral regurgitation in patients with heart failure. A quantitative analysis of 1256 patients with ischaemic and non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart 2011, 97, 1675–1680.

- D’Arcy, J.L.; Coffey, S.; Loudon, M.A.; Kennedy, A.; Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Birks, J.; Frangou, E.; Farmer, A.J.; Mant, D.; Wilson, J.; et al. Large-scale community echocardiographic screening reveals a major burden of undiagnosed valvular heart disease in older people: The OxVALVE Population Cohort Study. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 3515–3522.

- Singh, J.P.; Evans, J.C.; Levy, D.; Larson, M.G.; A Freed, L.; Fuller, D.L.; Lehman, B.; Benjamin, E.J. Prevalence and clinical determinants of mitral, tricuspid, and aortic regurgitation (the Framingham Heart Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 1999, 83, 897–902.

- Topilsky, Y.; Maltais, S.; Medina-Inojosa, J.; Oguz, D.; Michelena, H.; Maalouf, J.; Mahoney, D.W.; Enriquez-Sarano, M. Burden of Tricuspid Regurgitation in Patients Diagnosed in the Community Setting. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, 433–442.

- Benfari, G.; Antoine, C.; Miller, W.L.; Thapa, P.; Topilsky, Y.; Rossi, A.; Michelena, H.I.; Pislaru, S.; Enriquez-Sarano, M. Excess Mortality Associated with Functional Tricuspid Regurgitation Complicating Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2019, 140, 196–206.

- Chorin, E.; Rozenbaum, Z.; Topilsky, Y.; Konigstein, M.; Ziv-Baran, T.; Richert, E.; Keren, G.; Banai, S. Tricuspid regurgitation and long-term clinical outcomes. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 21, 157–165.

- E Bartko, P.; Hülsmann, M.; Hung, J.; Pavo, N.; A Levine, R.; Pibarot, P.; Vahanian, A.; Stone, G.W.; Goliasch, G. Secondary valve regurgitation in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction, and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2799–2810.

- Deferm, S.; Bertrand, P.B.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Verhaert, D.; Rega, F.; Thomas, J.D.; Vandervoort, P.M. Atrial Functional Mitral Regurgitation: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2465–2476.

- Magne, J.; Sénéchal, M.; Dumesnil, J.G.; Pibarot, P. Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation: A Complex Multifaceted Disease. Cardiology 2009, 112, 244–259.

- Lancellotti, P.; Moura, L.; Pierard, L.A.; Agricola, E.; Popescu, B.A.; Tribouilloy, C.; Hagendorff, A.; Monin, J.-L.; Badano, L.; Zamorano, J.L.; et al. European Association of Echocardiography recommendations for the assessment of valvular regurgitation. Part 2: Mitral and tricuspid regurgitation (native valve disease). Eur. Heart J.—Cardiovasc. Imaging 2010, 11, 307–332.

- Kajimoto, K.; Sato, N.; Takano, T.; on behalf of the investigators of the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Syndromes (ATTEND) registry. Functional mitral regurgitation at discharge and outcomes in patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure with a preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 1051–1059.

- Benfari, G.; Antoine, C.; Essayagh, B.; Batista, R.; Maalouf, J.; Rossi, A.; Grigioni, F.; Thapa, P.; Michelena, H.I.; Enriquez-Sarano, M. Functional Mitral Regurgitation Outcome and Grading in Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 2303–2315.

- Dziadzko, V.; Dziadzko, M.; Medina-Inojosa, J.R.; Benfari, G.; Michelena, H.I.; Crestanello, J.A.; Maalouf, J.; Thapa, P.; Enriquez-Sarano, M. Causes and Mechanisms of Isolated Mitral Regurgitation in the Community: Clinical Context and Outcome. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 2194–2202.

- Gertz, Z.M.; Raina, A.; Saghy, L.; Zado, E.S.; Callans, D.J.; Marchlinski, F.E.; Keane, M.G.; Silvestry, F.E. Evidence of Atrial Functional Mitral Regurgitation Due to Atrial Fibrillation: Reversal With Arrhythmia Control. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 1474–1481.

- Mesi, O.; Gad, M.M.; Crane, A.D.; Ramchand, J.; Puri, R.; Layoun, H.; Miyasaka, R.; Gillinov, M.A.; Wierup, P.; Griffin, B.P.; et al. Severe Atrial Functional Mitral Regurgitation: Clinical and Echocardiographic Characteristics, Management and Outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 797–808.

- Redfield, M.M.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Borlaug, B.A.; Rodeheffer, R.J.; Kass, D.A. Age- and Gender-Related Ventricular-Vascular Stiffening: A Community-Based Study. Circulation 2005, 112, 2254–2262.

- Lam, C.S.P.; Roger, V.L.; Rodeheffer, R.J.; Bursi, F.; Borlaug, B.A.; Ommen, S.R.; Kass, D.A.; Redfield, M.M. Cardiac Structure and Ventricular–Vascular Function in Persons with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction From Olmsted County, Minnesota. Circulation 2007, 115, 1982–1990.

- Kawaguchi, M.; Hay, I.; Fetics, B.; Kass, D.A. Combined Ventricular Systolic and Arterial Stiffening in Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction: Implications for Systolic and Diastolic Reserve Limitations. Circulation 2003, 107, 714–720.

- January, C.T.; Wann, L.S.; Calkins, H.; Chen, L.Y.; Cigarroa, J.E.; Cleveland, J.C., Jr.; Ellinor, P.T., Jr.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Field, M.E.; Furie, K.L.; et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in Collaboration with the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2019, 140, E28.

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation Developed in Collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the Special Contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 4194.

- Manning, W.J.; Silverman, D.I.; Katz, S.E.; Riley, M.F.; Come, P.C.; Doherty, R.M.; Munson, J.T.; Douglas, P.S. Impaired left atrial mechanical function after cardioversion: Relation to the duration of atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1994, 23, 1535–1540.

- Okamoto, C.; Okada, A.; Nishimura, K.; Moriuchi, K.; Amano, M.; Takahama, H.; Amaki, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Kanzaki, H.; Fujita, T.; et al. Prognostic comparison of atrial and ventricular functional mitral regurgitation. Open Heart 2021, 8, e001574.

- Enriquez-Sarano, M.; Benfari, G.; Messika-Zeitoun, D.; Grigioni, F.; Michelena, H.I. Functional mitral regurgitation: A proportionate or disproportionate focus of attention? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 1759–1762.

- Guta, A.C.; Badano, L.P.; Tomaselli, M.; Mihalcea, D.; Bartos, D.; Parati, G.; Muraru, D. The Pathophysiological Link between Right Atrial Remodeling and Functional Tricuspid Regurgitation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: A Three-Dimensional Echocardiography Study. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2021, 34, 585–594.e1.

- Muraru, D.; Addetia, K.; Guta, A.C.; Ochoa-Jimenez, R.C.; Genovese, D.; Veronesi, F.; Basso, C.; Iliceto, S.; Badano, L.P.; Lang, R.M. Right atrial volume is a major determinant of tricuspid annulus area in functional tricuspid regurgitation: A three-dimensional echocardiographic study. Eur. Heart J.—Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 22, 660–669.

- Hahn, R.T.; Badano, L.P.; Bartko, P.E.; Muraru, D.; Maisano, F.; Zamorano, J.L.; Donal, E. Tricuspid regurgitation: Recent advances in understanding pathophysiology, severity grading and outcome. Eur. Heart J.—Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 23, 913–929.

- Otto, C.M.; Nishimura, R.A.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P., 3rd; Gentile, F.; Jneid, H.; Krieger, E.V.; Mack, M.; McLeod, C.; et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 450–500.

- Fagot, J.; Lavie-Badie, Y.; Blanchard, V.; Fournier, P.; Galinier, M.; Carrié, D.; Lairez, O.; Cariou, E.; Alric, L.; Bureau, C.; et al. Impact of tricuspid regurgitation on survival in patients with cardiac amyloidosis. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 438–446.

- Nusca, A.; Cammalleri, V.; Carpenito, M.; Bono, M.C.; Mega, S.; Grigioni, F.; Ussia, G.P. Percutaneous Repair of Atrial Functional Tricuspid Regurgitation in Cardiac Amyloidosis: Combining Linear with Lateral Thinking. JACC Case Rep. 2023, 5, 101685.

- Mascherbauer, J.; Kammerlander, A.A.; Zotter-Tufaro, C.; Aschauer, S.; Duca, F.; Dalos, D.; Winkler, S.; Schneider, M.; Bergler-Klein, J.; Bonderman, D. Presence of ´isolated´ tricuspid regurgitation should prompt the suspicion of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171542.

- Fender, E.A.; Petrescu, I.; Ionescu, F.; Zack, C.J.; Pislaru, S.V.; Nkomo, V.T.; Cochuyt, J.J.; Hodge, D.O.; Nishimura, R.A. Prognostic Importance and Predictors of Survival in Isolated Tricuspid Regurgitation: A Growing Problem. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 2032–2039.

- Ren, Q.; Li, X.; Fang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, M.; Yu, Y.; Liao, S.; Tse, H.; Yiu, K. The prevalence, predictors, and prognosis of tricuspid regurgitation in stage B and C heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 4051–4060.

- Topilsky, Y.; Nkomo, V.T.; Vatury, O.; Michelena, H.I.; Letourneau, T.; Suri, R.M.; Pislaru, S.; Park, S.; Mahoney, D.W.; Biner, S.; et al. Clinical Outcome of Isolated Tricuspid Regurgitation. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 7, 1185–1194.

- Chen, E.; L’official, G.; Guérin, A.; Dreyfus, J.; Lavie-Badie, Y.; Sportouch, C.; Eicher, J.-C.; Maréchaux, S.; Le Tourneau, T.; Oger, E.; et al. Natural history of functional tricuspid regurgitation: Impact of cardiac output. Eur. Heart J.—Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 22, 878–885.

- Hell, M.M.; Emrich, T.; Kreidel, F.; Kreitner, K.-F.; Schoepf, U.J.; Münzel, T.; von Bardeleben, R.S. Computed tomography imaging needs for novel transcatheter tricuspid valve repair and replacement therapies. Eur. Heart J.—Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 22, 601–610.

- Bartko, P.E.; Arfsten, H.; Frey, M.; Heitzinger, G.; Pavo, N.; Cho, A.N.N.A.; Neuhold, S.; Tan, T.; Strunk, G.; Hengstenberg, C.; et al. 5937Natural history of functional tricuspid regurgitation: Implications of quantitative doppler assessment. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, 389–397.

- Santas, E.; Chorro, F.J.; Miñana, G.; Méndez, J.; Muñoz, J.; Escribano, D.; García-Blas, S.; Valero, E.; Bodí, V.; Núñez, E.; et al. Tricuspid Regurgitation and Mortality Risk Across Left Ventricular Systolic Function in Acute Heart Failure. Circ. J. 2015, 79, 1526–1533.

- Topilsky, Y.; Inojosa, J.M.; Benfari, G.; Vaturi, O.; Maltais, S.; Michelena, H.; Mankad, S.; Enriquez-Sarano, M. Clinical presentation and outcome of tricuspid regurgitation in patients with systolic dysfunction. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3584–3592.

- Gavazzoni, M.; Heilbron, F.; Badano, L.P.; Radu, N.; Cascella, A.; Tomaselli, M.; Perelli, F.; Caravita, S.; Baratto, C.; Parati, G.; et al. The atrial secondary tricuspid regurgitation is associated to more favorable outcome than the ventricular phenotype. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1022755.

- Dietz, M.F.; Prihadi, E.A.; van der Bijl, P.; Goedemans, L.; Mertens, B.J.; Gursoy, E.; van Genderen, O.S.; Marsan, N.A.; Delgado, V.; Bax, J.J. Prognostic Implications of Right Ventricular Remodeling and Function in Patients with Significant Secondary Tricuspid Regurgitation. Circulation 2019, 140, 836–845.

- Itelman, E.; Vatury, O.; Kuperstein, R.; Ben-Zekry, S.; Hay, I.; Fefer, P.; Barbash, I.; Klempfner, R.; Segev, A.; Feinberg, M.; et al. The Association of Severe Tricuspid Regurgitation with Poor Survival Is Modified by Right Ventricular Pressure and Function: Insights from SHEBAHEART Big Data. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2022, 35, 1028–1036.

More