Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 1 by Wilfried Yves Hamilton Adoni.

Uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs), also known as drones, are ubiquitous and their use cases extend today from governmental applications to civil applications such as the agricultural, medical, and transport sectors, etc. In accordance with the requirements in terms of demand, it is possible to carry out various missions involving several types of UAVs as well as various onboard sensors.

- UAV

- RPAS

- UAS

- uncrewed aerial vehicles

- UAV Classifcation

1. Introduction

Uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) or drones [1] belong to the large family of connected objects. After being utilized extensively in military operations [2[2][3],3], drones have remained out of reach for civilians [4] due to their high price. With recent innovations in micro-controllers and sensors, drone prices have been reduced to become affordable. Currently, they are widely used for commercial purposes such as surveys, photography, and cinematography. UAVs, in general, are outfitted with on-board sensors that allow them to collect geospatial information about their environment and are remotely controlled from a ground control station [5]. From this station, the operator can plan and supervise the evolution of the mission. Their use in the civil and industrial sector [4] has allowed us to optimize industrial processes or to carry out missions in hostile environments that are partially or entirely inaccessible to humans [6,7,8,9][6][7][8][9]. For example, in the agricultural field, farmers are now facing various problems that impact the quality of their crops. Drones are an efficient and cheap means to collect information on ecosystems and their variations due to, e.g., climate change, soil erosion, water availability, and meteorological extreme events. They are, for example, also used in spraying plantations, which saves time and optimizes yields [10]. Goodrich Payton et al. [11] have demonstrated the efficiency of drones in precision agriculture. From the collected data, they reconstructed a 3D cartographic representation of the plots to better analyze the density of vegetation and soil heterogeneities.

Drones provide a broad variety of purposes in the health sector, including delivering medical supplies to remote or hard-to-reach areas, e.g., transporting blood samples and lab results [12]. In the field of transportation, drones can be used for package delivery [13[13][14][15],14,15], traffic monitoring [16], and infrastructure inspections [17]. Drones have also been used to map volcanoes’ terrain and to detect volcanic activity. Thiele et al. [5] used drones equipped with thermal cameras, gas sensors, and other instruments to measure temperature, gas concentrations, and other indicators of volcanic activity. This information can be used to predict eruptions, to elaborate rescue operations, for photogrammetry and infrastructure monitoring, or even for delivery services. UAVs can also be used to study the geology of a volcano and its surrounding area, providing valuable information for volcano research. The use of UAVs in this field can greatly improve the efficiency, accuracy, and safety of operations, as well as decrease costs by reducing the need for human intervention in dangerous areas [5]. However, it implies several challenges related to communication services, such the range, security system, and communication architecture [18].

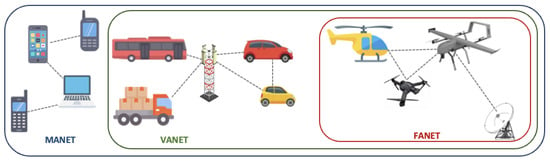

The communication architecture of drones relies on a Flying Ad-Hoc Network (FANET) [19], without the requirement for a fixed infrastructure. FANET is a decentralized ad-hoc network that enables communication between the ground station and flying vehicles, such as drones and aircraft [20]. As shown in Figure 1, FANET inherits from both Vehicular Ad-Hoc Network (VANET) [21] and Mobile Ad-Hoc Network (MANET) [22] networks. It is a subclass of MANET that is an extension to highly mobile devices such as smartphones and laptops. These three types of ad-hoc networks share the ability to form and maintain a network connection dynamically [23]. Combined, they are an effective tool in creating a wide-area network that links UAVs, vehicles, and communication devices. They can also be used for applications such as collision avoidance [24], traffic jam prevention, and intelligent transportation systems [25].

As the need for UAVs grows, there is an increasing requirement for systems that can coordinate several UAVs in a dispersed environment [1,26][1][26]. This is where multi-UAV systems are relevant. Multi-UAV systems, commonly called swarms, are composed of multiple UAVs that are coordinated to collaborate in order to accomplish a shared purpose [27]. These systems have the potential to coordinate mission tasks across multiple UAVs in a parallel manner. They have several possible applications, including rescue missions [7,28][7][28], surveillance and reconnaissance [6,26[6][26][29][30],29,30], environmental monitoring [17], and even payload carrying [13,14,15][13][14][15]. One of the primary benefits of swarms is their capacity to operate cohesively, allowing them to cover large regions quickly and make choices collectively, making them more robust to failure than individual UAVs [31]. Swarms operate according to the design of a multi-UAV system architecture that is controlled by a central system [6] or through decentralized algorithms [1,32,33][1][32][33].

To work in a coordinated manner, a multi-UAV system requires the following key components. (1) The UAVs themselves: these are the drones that make up the swarm. (2) A ground control station: this is the central point of control for the drone swarm. It oversees the transmission of commands to the drones, as well as the retrieval of data from them. It can be a single computer or a cluster of computing nodes. (3) A communication system: it consists of devices and antennas that enable communication between the drones and the ground station via a common protocol. The communication system can use a variety of technologies, including MANET [22], FANET [19], and VANET [21]. (4) A navigation system: this is the system that enables the UAVs to fly and locate themselves in the environment. It includes sensors such as GPS and Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs). (5) A control system: it allows the ground station to control the drones and to coordinate their actions. It consists of software for mission planning, decision making, and swarm behavior. (6) Finally, a data processing system: this is the system that allows the ground station to process the data in real time and feed the data back to the control system. It can include tools for image processing, data analysis, and machine learning. All these components work together to allow the swarm to function as a cohesive unit, with the ground station providing overall command and control, while the UAVs collaborate to attain a common aim.

Depending upon the operations’ nature and mission requirements, the architecture of a multi-UAV system might be centralized [6] or decentralized [32,33][32][33]. Because of its complexity and the very dynamic environment of operation, there are several challenges related to using multi-UAV for highly mobile networks operating in large-area missions:

-

Communication: maintaining communication between the drones in a swarm can be challenging, especially in highly mobile and wide areas. The drones must be able to maintain communication even when they are moving at high speeds or when they are far apart from each other.

- Communication: maintaining communication between the drones in a swarm can be challenging, especially in highly mobile and wide areas. The drones must be able to maintain communication even when they are moving at high speeds or when they are far apart from each other.

- Coordination

- : coordinating the actions of the UAVs is complex, especially in elaborate missions. To reach a shared purpose, the drones must be able to successfully collaborate.

-

Autonomy: the drones must be able to operate autonomously without human intervention. This requires collaborative actions for decision making, navigation, and swarm behavior. Theses challenges include spatial awareness, maintaining a distance from each other, and communicating potential threats to other drones, such as heavy wind gusts, rain, and obstructions.

As shown in

Table 2

, four classes of UAVs, organized as very small, small, medium, and large, are usually defined.

Table 2.

UAV classification according to the size (

, accessed on 15 March 2023).

| Size | Dimensions (m2) |

Payload (kg) |

Velocity (km/h) |

Altitude (km) |

Example (Accessed on 15 March 2023) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very small | 0.3–0.5 | <9 | ≤10 | <0.12 | SmartPlane Pro (https://www.drohnen.de/tag/tobyrich/) DJI Mavic 3 (https://store.dji.com/de/product/dji-mavic-3) |

| Small | 0.51–2 | <185 | <0.4 | Wingcopter 198 (https://wingcopter.com/) Astro (https://freeflysystems.com/alta-x) Scorpion (https://www.quantum-systems.com/) |

|

| Medium | 5–10 | <200 | <463 | <1.1 | Trinity F90+ (https://www.quantum-systems.com/) Vector (https://www.quantum-systems.com/) |

- Scalability

- : multi-UAV systems must be able to support a large number of drones, they must be reliable, and they must be able to scale up or down depending on the requirements of the mission.

-

Reliability: the system must be reliable, even if one or more UAVs fail. This requires robust algorithms for fault detection, diagnosis, and recovery.

- Coordination: coordinating the actions of the UAVs is complex, especially in elaborate missions. To reach a shared purpose, the drones must be able to successfully collaborate.

- Autonomy: the drones must be able to operate autonomously without human intervention. This requires collaborative actions for decision making, navigation, and swarm behavior. Theses challenges include spatial awareness, maintaining a distance from each other, and communicating potential threats to other drones, such as heavy wind gusts, rain, and obstructions.

- ,

- ,

- Scalability

- : multi-UAV systems must be able to support a large number of drones, they must be reliable, and they must be able to scale up or down depending on the requirements of the mission.

- ].

- Reliability

- : the system must be reliable, even if one or more UAVs fail. This requires robust algorithms for fault detection, diagnosis, and recovery.

- 2.

-

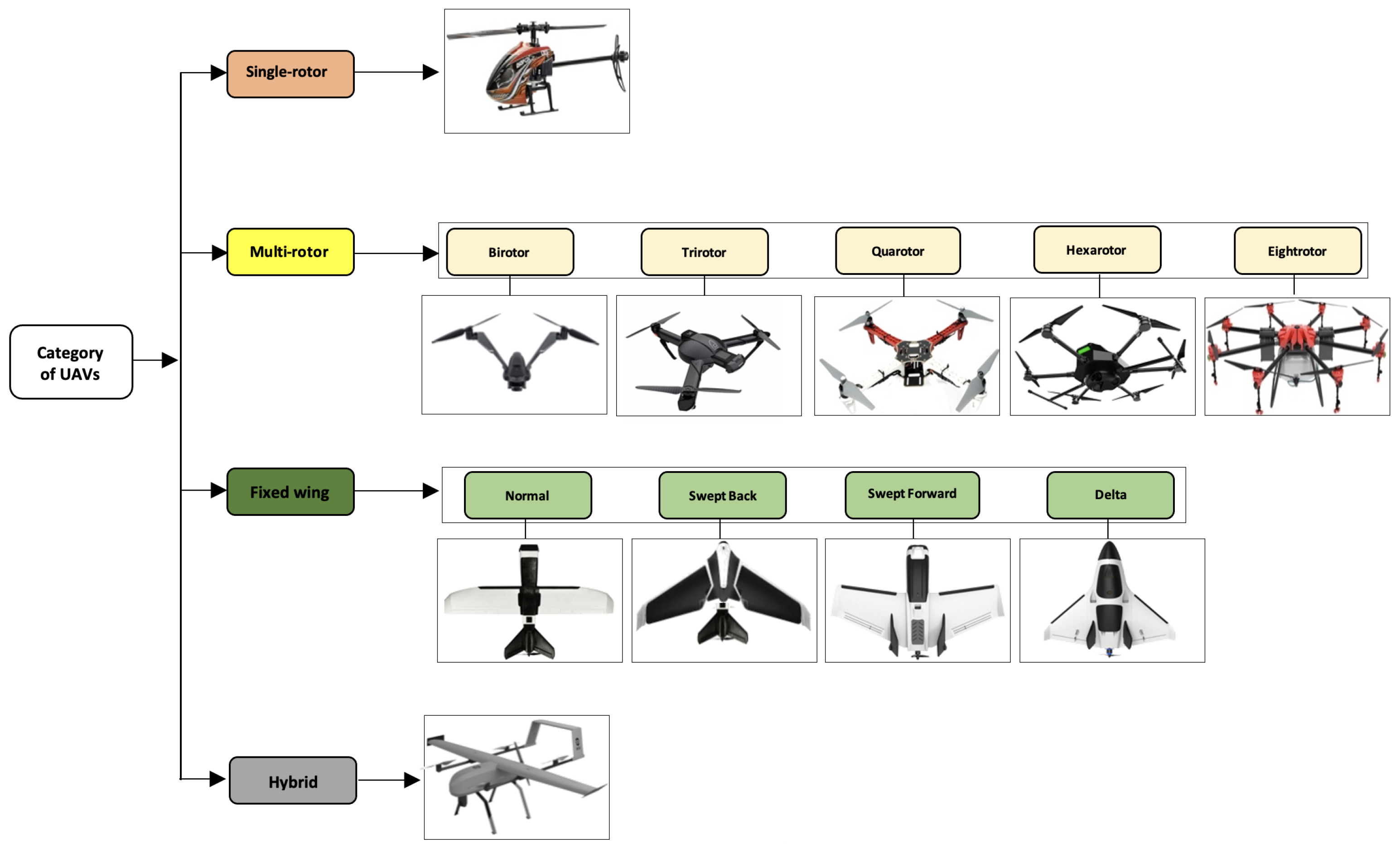

Multi-rotor [51][47] (or multicopter): this is a UAV having more than two rotors. This UAV category is further subdivided into five sub-categories, which are birotor, trirotor, quadrotor, hexarotor, and eight-rotor (octocopter) [13,15][13][15]. As with single-rotor UAVs, multi-rotor UAVs also ensure a vertical takeoff and landing. They are fast and agile in flight, allowing them to perform complex maneuvers and flights in confined spaces. However, the short flight time is the main weakness of these types of aircraft.

- 3.

-

Fixed-wing [52][48]: the navigation principle of this category of UAVs is based on a simple structure of a fixed rigid wing. The classification of these drones is not only based on the type of wing, but also on the body and the power system (Li-ion, Li-Po batteries, or gas-powered). They are subdivided into four subcategories: normal, swept back, swept forward, and delta. Furthermore, they can carry heavier payloads than multi-rotors [53][49]. The disadvantage of these UAVs is that they have limited agility in flight, which does not allow them to perform complex maneuvers and fly over confined spaces, as well as the necessity for a runway for takeoff and landing.

- 4.

-

Hybrid [54][50]: this last category is still under development. It is an improved version that takes advantage of both multi-rotor and fixed-wing UAVs. They offer good agility and velocity on long-distance flights. They can carry large payloads and do not require a runway. The main disadvantages are the high price, the complicated mechanics, and the lower performance in terms of flight stability and the restrictive speed ranges.Table 1.Comparative study of UAVs: advantages vs. disadvantages.

Categories Strengths Weak Points Single-rotor Heavy payload

Flight time

Hovering flight

VTOLMechanical system

Rotor sizeMulti-rotor Hovering flight

VTOL

Velocity

Agile maneuverability

Confined-space flyingFlight time Fixed-wing Flight time

High Velocity

Large-area coverageComplex aerofoil

Limited payload

No hovering flight

Limited maneuverabilityAlta X ( https://freeflysystems.com/alta-x ) Yangda YD6-1600S ( https://www.yangdaonline.com/) Hybrid Flight time

Hovering flight

VTOL

Agile maneuverability

Velocity

Large-area coverageVery expensive

Unstable transition mechanism from

horizontal to vertical flightLarge >10 <600 - Security

- : a multi-UAV system must be encrypted, guarding against hacking, jamming, and other types of interference to the drones and their communications [

- Security

- : a multi-UAV system must be encrypted, guarding against hacking, jamming, and other types of interference to the drones and their communications

- [

- 18

- ]

- [34][35

- Interference

- : in highly dynamic surroundings, drones may encounter interference from other wireless devices, which can affect communication or navigation [

- ].

- ]

- .

- Interference

- : in highly dynamic surroundings, drones may encounter interference from other wireless devices, which can affect communication or navigation

- [

- 18

- ]

- .

- Energy consumption

- : to ensure that the drones can operate for long periods of time, energy management is crucial. Drones must be able to manage their power consumption and plan their routes to optimize battery life [

- ,

- ,

- Energy consumption

- : to ensure that the drones can operate for long periods of time, energy management is crucial. Drones must be able to manage their power consumption and plan their routes to optimize battery life

- [

- 35

- ]

- [

- 36][37][38][39][40][41][42].

- Interoperability

- : the system must guarantee the exchange of information between different types of drones regardless of their communication protocols. Unfortunately, there is still no common protocol for drones to communicate with each other.

- Interoperability

- : the system must guarantee the exchange of information between different types of drones regardless of their communication protocols. Unfortunately, there is still no common protocol for drones to communicate with each other.

2. Classification of UAVs

The growing interest in UAVs in recent years has led to the strong emergence of various types of aircraft with varying configurations and components in terms of shape and size. UAVs are divided into four types: single-rotor, multi-rotor, fixed-wing, and hybrid [33], as shown in Figure 42. Figure 42.Different categories of UAVs.

Figure 42.Different categories of UAVs.- 1.

-

Single-rotor [50][46]

<5.5 Primoco UAV One 150 ( https://uav-stol.com/primoco-uav-one-150/ ) Feng Ru 3-100 ( https://ev.buaa.edu.cn/info/1133/3165.htm ) Very small UAVs refer to micro- or nano-UAVs. These UAVs resemble insects or birds with wings, and their dimensions generally vary between 5 and 50 cm. The components are extremely small and lightweight. They can reach a top speed of >10 km/h and are limited to a maximum altitude of ca. 120 m by law. Typical examples of very small UAVs include the German TobyRich SmartPlane Pro (https://www.drohnen.de/tag/tobyrich/, accessed on 15 March 2023) with a wing length of 30 cm; it is ultra-stable and equipped with a VGA camera of 640 × 480 pixels. Moreover, the DJI Mavic 3 (https://store.dji.com/de/product/dji-mavic-3, accessed on 15 March 2023), configured with dimensions of 28.3 × 10.7 cm2, is another small model of UAV; it is equipped with a 4:3 CMOS camera and can fly for 46 min with a maximum transmission range of ca. 15 km.Small UAVs, often known as mini-UAVs, refer to UAVs whose dimensions exceed at least 50 cm and not more than 2 m. The design of these aircraft is essentially based on the fixed-wing model, and the majority are launched by propelling them into the air by the operator. They can carry a maximum payload of 9 kg and fly at a maximum speed of ca. 150 km/h at an altitude usually not exceeding 400 m. The German Wingcopter 198 (https://wingcopter.com/, accessed on 15 March 2023) is an electric VTOL drone used for delivery services. It is designed with a configuration of 198 × 154 cm2 with a flight time of 90 min. It is hybrid and can fly in both multicopter and fixed-wing modes. The second one is Astro (https://freeflysystems.com/alta-x, accessed on 15 March 2023), a quadrotor designed with a configuration of 141 × 51 cm2 with a flight time of 37 min. It incorporates a gimbaled a7R IV mapping camera and the data transfer is based on the MAVLink communication protocol [55][51]. The last one is Scorpion (https://www.quantum-systems.com/, accessed on 15 March 2023), a VTOL that has a wingspan of 1.37 m2 and a flight endurance of 35 min. It provides data transfer up to a range of 25 km and it supports a maximum weight of >7 kg.A UAV is considered “medium” if it is too heavy to be handled by one person but smaller than an aeroplane, since they can only carry a payload of 200 kg. They are usually in the category of fixed-wing UAVs and typically have a wingspan whose length ranges from 5 to 10 m. They can fly at a maximum velocity of 463 km/h without exceeding an altitude of almost 1 km. There are numerous examples of UAVs in this scope of size, such as the Trinity F90+ (https://www.quantum-systems.com/, accessed on 15 March 2023), Vector (https://www.quantum-systems.com/, accessed on 15 March 2023), Alta X (https://freeflysystems.com/alta-x, accessed on 15 March 2023), and, recently, the Yangda YD6-1600S (https://www.yangdaonline.com/, accessed on 15 March 2023). The German intelligent VTOL Trinity F90+ and Vector have average fixed wings of 2.8 m and, respectively, a flight time of 90 min and 120 min. The Alta X is a VTOL quadrotor with a 50 min flight time and it carries a maximum payload of 15 kg for 8 min. It has a peak speed of more than >95 km/h and uses the MAVLink [55][51] protocol for data transmission. The hexacopter Yangda YD6-1600S is designed with dimensions of 1.6 × 2.35 m2. It can reach a cruise speed of >72 km/h and can also carry a maximum payload of 5 kg for a flight time not exceeding 45 min.The last class of UAVs is mainly used for military purposes. The large UAVs have a wide range and endurance. Furthermore, their designs are usually based on a fixed-wing structure, which allows them to carry heavy payloads over long distances while reaching a maximum altitude of 5.5 km. Some examples of these UAVs are the Czech Primoco UAV One 150 (https://uav-stol.com/primoco-uav-one-150/, accessed on 15 March 2023) and the Chinese Feng Ru 3-100 (https://ev.buaa.edu.cn/info/1133/3165.htm, accessed on 15 March 2023). Primoco is designed to fly for 15 h. It can carry a payload of 50 kg and has a radio range of 200 km. Feng Ru is designed for couriers; it has a wingspan of 19.6 m and can fly for 5 days.

References

- Chen, X.; Tang, J.; Lao, S. Review of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Swarm Communication Architectures and Routing Protocols. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3661.

- Lachow, I. The upside and downside of swarming drones. Bull. At. Sci. 2017, 73, 96–101.

- Scharre, P. Robotics on the Battlefield Part II: The Coming Swarm; Technical Report; Center for a New American Security: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Shakhatreh, H.; Sawalmeh, A.H.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Dou, Z.; Almaita, E.; Khalil, I.; Othman, N.S.; Khreishah, A.; Guizani, M. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Survey on Civil Applications and Key Research Challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48572–48634.

- Thiele, S.T.; Varley, N.; James, M.R. Thermal photogrammetric imaging: A new technique for monitoring dome eruptions. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2017, 337, 140–145.

- Chriki, A.; Touati, H.; Snoussi, H.; Kamoun, F. UAV-GCS Centralized Data-Oriented Communication Architecture for Crowd Surveillance Applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Tangier, Morocco, 24–28 June 2019; IEEE: Tangier, Morocco, 2019; pp. 2064–2069.

- Scherer, J.; Yahyanejad, S.; Hayat, S.; Yanmaz, E.; Andre, T.; Khan, A.; Vukadinovic, V.; Bettstetter, C.; Hellwagner, H.; Rinner, B. An Autonomous Multi-UAV System for Search and Rescue. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Micro Aerial Vehicle Networks, Systems, and Applications for Civilian Use, DroNet ’15, Florence, Italy, 18 May 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 33–38.

- Adamopoulos, E.; Rinaudo, F. UAS-Based Archaeological Remote Sensing: Review, Meta-Analysis and State-of-the-Art. Drones 2020, 4, 46.

- Patel, M.; Bandopadhyay, A.; Ahmad, A. Collaborative Mapping of Archaeological Sites Using Multiple UAVs. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Autonomous Systems 16; Ang, M.H., Jr., Asama, H., Lin, W., Foong, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 54–70.

- Rejeb, A.; Abdollahi, A.; Rejeb, K.; Treiblmaier, H. Drones in agriculture: A review and bibliometric analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107017.

- Goodrich, P.; Betancourt, O.; Arias, A.C.; Zohdi, T. Placement and drone flight path mapping of agricultural soil sensors using machine learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107591.

- Febria, J.; Dewi, C.; Mailoa, E. Comparison of Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem Using Initial Route and Without Initial Route for Pharmaceuticals Distribution. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Innovative and Creative Information Technology (ICITech), Salatiga, Indonesia, 23–25 September 2021; pp. 94–98.

- Mellinger, D.; Shomin, M.; Michael, N.; Kumar, V. Cooperative Grasping and Transport Using Multiple Quadrotors. In Distributed Autonomous Robotic Systems: The 10th International Symposium; Martinoli, A., Mondada, F., Correll, N., Mermoud, G., Egerstedt, M., Hsieh, M.A., Parker, L.E., Støy, K., Eds.; Springer Tracts in Advanced Robotics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 545–558.

- Ritz, R.; D’Andrea, R. Carrying a flexible payload with multiple flying vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013; IEEE: Tokyo, Japan, 2013; pp. 3465–3471.

- Loianno, G.; Kumar, V. Cooperative Transportation Using Small Quadrotors Using Monocular Vision and Inertial Sensing. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 680–687.

- Menouar, H.; Guvenc, I.; Akkaya, K.; Uluagac, A.S.; Kadri, A.; Tuncer, A. UAV-Enabled Intelligent Transportation Systems for the Smart City: Applications and Challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 22–28.

- Stan, A.C. A decentralised control method for unknown environment exploration using Turtlebot 3 multi-robot system. In Proceedings of the 2022 14th International Conference on Electronics, Computers and Artificial Intelligence (ECAI), Ploiesti, Romania, 30 June–1 July 2022; pp. 1–6.

- Choudhary, G.; Sharma, V.; Gupta, T.; Kim, J.; You, I. Internet of Drones (IoD): Threats, Vulnerability, and Security Perspectives. Res. Briefs Inf. Commun. Technol. Evol. 2018, 4, 64–77.

- Al-Emadi, S.; Al-Mohannadi, A. Towards Enhancement of Network Communication Architectures and Routing Protocols for FANETs: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Advanced Communication Technologies and Networking (CommNet), Marrakech, Morocco, 4–6 September 2020; IEEE: Marrakech, Morocco, 2020; pp. 1–10.

- Agrawal, J.; Kapoor, M. A comparative study on geographic-based routing algorithms for flying ad-hoc networks. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2021, 33, e6253.

- Rizwan Ghori, M.; Safa Sadiq, A.; Ghani, A. VANET Routing Protocols: Review, Implementation and Analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1049, 012064.

- Hogie, L.; Bouvry, P.; Guinand, F. An Overview of MANETs Simulation. Electron. Notes Theor. Comput. Sci. 2006, 150, 81–101.

- Khan, M.A.; Khan, I.U.; Safi, A.; Quershi, I.M. Dynamic Routing in Flying Ad-Hoc Networks Using Topology-Based Routing Protocols. Drones 2018, 2, 27.

- Digulescu, A.; Despina-Stoian, C.; Stănescu, D.; Popescu, F.; Enache, F.; Ioana, C.; Rădoi, E.; Rîncu, I.; Șerbănescu, A. New Approach of UAV Movement Detection and Characterization Using Advanced Signal Processing Methods Based on UWB Sensing. Sensors 2020, 20, 5904.

- Jabbar, R.; Dhib, E.; ben Said, A.; Krichen, M.; Fetais, N.; Zaidan, E.; Barkaoui, K. Blockchain technology for intelligent transportation systems: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 20995–21031.

- Ahmadzadeh, A.; Jadbabaie, A.; Kumar, V.; Pappas, G.J. Multi-UAV Cooperative Surveillance with Spatio-Temporal Specifications. In Proceedings of the 45th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–15 December 2006; IEEE: San Diego, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 5293–5298.

- Abdelkader, M.; Güler, S.; Jaleel, H.; Shamma, J.S. Aerial Swarms: Recent Applications and Challenges. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2021, 2, 309–320.

- Khalil, H.; Rahman, S.U.; Ullah, I.; Khan, I.; Alghadhban, A.J.; Al-Adhaileh, M.H.; Ali, G.; ElAffendi, M. A UAV-Swarm-Communication Model Using a Machine-Learning Approach for Search-and-Rescue Applications. Drones 2022, 6, 372.

- Petrlik, M.; Vonasek, V.; Saska, M. Coverage optimization in the Cooperative Surveillance Task using Multiple Micro Aerial Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC), Bari, Italy, 6–9 October 2019; IEEE: Bari, Italy, 2019; pp. 4373–4380.

- Perez, D.; Maza, I.; Caballero, F.; Scarlatti, D.; Casado, E.; Ollero, A. A Ground Control Station for a Multi-UAV Surveillance System: Design and Validation in Field Experiments. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2013, 69, 119–130.

- Aljehani, M.; Inoue, M. Communication and Autonomous Control of Multi-UAV System in Disaster Response Tasks. In Agent and Multi-Agent Systems: Technology and Applications; Jezic, G., Kusek, M., Chen-Burger, Y.H.J., Howlett, R.J., Jain, L.C., Eds.; Series Title: Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 74, pp. 123–132.

- Skorobogatov, G.; Barrado, C.; Salamí, E. Multiple UAV Systems: A Survey. Unmanned Syst. 2020, 08, 149–169.

- Maza, I.; Ollero, A.; Casado, E.; Scarlatti, D. Classification of Multi-UAV Architectures. In Handbook of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles; Valavanis, K.P., Vachtsevanos, G.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 953–975.

- Krichen, M.; Adoni, W.Y.H.; Mihoub, A.; Alzahrani, M.Y.; Nahhal, T. Security Challenges for Drone Communications: Possible Threats, Attacks and Countermeasures. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference of Smart Systems and Emerging Technologies (SMARTTECH), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 9–11 May 2022; pp. 184–189.

- Citroni, R.; Di Paolo, F.; Livreri, P. A Novel Energy Harvester for Powering Small UAVs: Performance Analysis, Model Validation and Flight Results. Sensors 2019, 19, 1771.

- Hajijamali Arani, A.; Azari, M.M.; Hu, P.; Zhu, Y.; Yanikomeroglu, H.; Safavi-Naeini, S. Reinforcement Learning for Energy-Efficient Trajectory Design of UAVs. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 9060–9070.

- Chen, Y.; Baek, D.; Bocca, A.; Macii, A.; Macii, E.; Poncino, M. A Case for a Battery-Aware Model of Drone Energy Consumption. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Telecommunications Energy Conference (INTELEC), Turino, Italy, 7–11 October 2018; pp. 1–8.

- Zhang, J.; Campbell, J.F.; Sweeney II, D.C.; Hupman, A.C. Energy consumption models for delivery drones: A comparison and assessment. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 90, 102668.

- Dorling, K.; Heinrichs, J.; Messier, G.G.; Magierowski, S. Vehicle Routing Problems for Drone Delivery. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2017, 47, 70–85.

- Chethan, R.; Kar, I. Multi-Agent Coverage Path Planning using a Swarm of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 19th India Council International Conference (INDICON), Kochi, India, 24–26 November 2022.

- Zhang, S.; Cheng, T. Optimizing Energy Consumption of Rotor UAV by Path Planning. In Proceedings of the 2022 Global Conference on Robotics, Artificial Intelligence and Information Technology (GCRAIT), Chicago, IL, USA, 30–31 July 2022; pp. 54–58.

- Galkin, B.; Kibilda, J.; DaSilva, L.A. UAVs as Mobile Infrastructure: Addressing Battery Lifetime. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2019, 57, 132–137.

- Pasek, P.; Kaniewski, P. A review of consensus algorithms used in Distributed State Estimation for UAV swarms. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 16th International Conference on Advanced Trends in Radioelectronics, Telecommunications and Computer Engineering (TCSET), Lviv-Slavske, Ukraine, 22–26 February 2022; pp. 472–477.

- Safavi, S.; Khan, U.A. Dynamic leader-follower algorithms in mobile multi-agent networks. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Digital Signal Processing (DSP), Singapore, 21–24 July 2015; pp. 10–13.

- Cao, Y.; Yu, W.; Ren, W.; Chen, G. An Overview of Recent Progress in the Study of Distributed Multi-Agent Coordination. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2013, 9, 427–438.

- Zhao, P.; Quan, Q.; Chen, S.; Tang, D.; Deng, Z. Experimental investigation on hover performance of a single-rotor system for Mars helicopter. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 582–591.

- Segui-Gasco, P.; Al-Rihani, Y.; Shin, H.S.; Savvaris, A. A Novel Actuation Concept for a Multi Rotor UAV. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2014, 74, 173–191.

- Cai, G.; Lum, K.Y.; Chen, B.M.; Lee, T.H. A brief overview on miniature fixed-wing unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE ICCA 2010, Xiamen, China, 9–11 June 2010; pp. 285–290.

- Boon, M.A.; Drijfhout, A.P.; Tesfamichael, S. Comparison of a Fixed-Wing and Multi-Rotor UAV for Environmental Mapping Applications: A Case Study. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-2/W6, 47–54.

- Saeed, A.S.; Younes, A.B.; Cai, C.; Cai, G. A survey of hybrid Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2018, 98, 91–105.

- DJI Mavic 3 Bestellen-DJI Store. Available online: https://store.dji.com/de/product/dji-mavic-3?vid=109821 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

More