2. Discovery and Ontogeny of Microglia

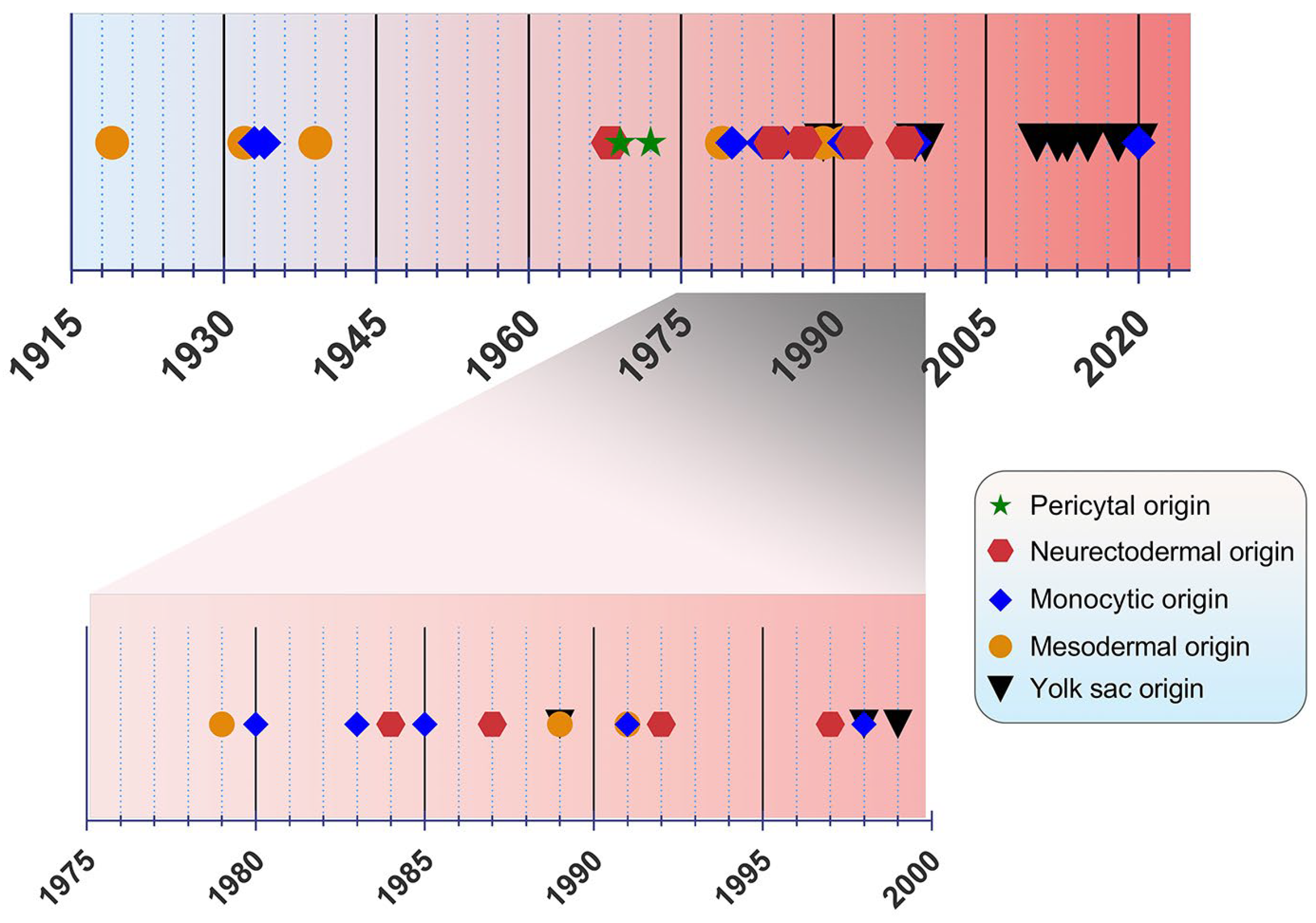

The origin of microglia has been a debated topic for years. In the past, four main origin concepts have been proposed as a source of microglia: (i) the mesodermal-associated mater elements, (ii) the neuroectodermal matrix cells, (iii) the pericytes, and (iv) the invasion of monocytes especially during early development (

Figure 1)

[20]. Río Hortega was hailed as the “Father of Microglia”, because their discovery supported the mesodermal origin, after observing the invasion of the pial elements within the CNS parenchyma

[13][21][13,21]. Using comparable staining methods, John Kershman agreed on the mesenchymal origin of microglia, which were found to be genetically related to histiocytes, a stationary phagocytic cell present in connective tissue

[22]. With reference to Boya et al., the meningeal envelope was proposed to be the source of microglia, which sustains a mesodermal nature in agreement with the classical experiments by Río Hortega

[23][24][23,24]. Later, the theory of multiple mesodermal sources of microglia depending on time and localization was posited

[25]. However, another study proposed vascular pericytes as the parent cells of microglia

[26][27][26,27]. The first reports on the monocytic origin of microglia came to the fore in 1933 and 1934 from Santha and Juba, respectively, who hypothesized that ramified microglia originated from circulating monocytes because the initial appearance of these cells coincided with the vascularization of the brain

[28][29][28,29].

Figure 1. Timeline view of microglial origin since their discovery by Río Hortega.

In the following decades, many researchers accepted this view, demonstrating microglial monocytic identity when investigating their origin

[30][31][32][33][30,31,32,33], while others rejected the possibility that microglia are derived from mononuclear blood cells

[34]. In 1968, autoradiography experiments performed with tritiated thymidine were conducted in adult

rats, showing that cells of the subependymal layer give rise to a number of glial cell types, such as astrocytes and microglia, offering a different perspective regarding microglial origin

[35]. The neuroectodermal origin was also supported by Kitamura et al., implying that glioblasts are the source of both astrocytes and microglia in

mice [36]. It was also proposed that microglia and astroglia have a common progenitor cell developing from neuroepithelial cells

[37]. Performing non-radioactive in situ hybridization and immunoperoxidase techniques, only a small population of microglia were found to be derived from bone marrow progenitors, because most of the cells were shown to be generated from locally residing precursors with a neuroectodermal ontogeny

[38]. The non-monocytic origin of microglia favored by Schelper and Adrian implicated that these cells are CNS intrinsic ones, enforcing the above theory of a neuroectodermal origin

[39].

The view of the origin of microglia from the YS was first introduced in 1989

[40][42]. A nucleoside diphosphatase histochemical study was conducted to evaluate the distribution of microglia in the developing

human CNS, implying that mesenchymal cells with haemopoietic potential migrate into neural tissues and then give rise to cells resembling microglia

[41][43]. Likewise, primitive macrophages of YS were found to be derived from fetal macrophages before the appearance of pro-monocytes/monocytes colonizing the embryonic tissues in

mice [40][42]. In an

avian model, microglia precursors were demonstrated to invade neural tissue from the pial surface and proliferated inside the CNS, indicating that their penetration through the embryonic CNS vessels is not possible

[42][44]. However, a

human embryogenesis study using lectin

+ and CD68

+ markers revealed two populations of microglia, indicating two different potential origins, specifically from the YS and bone marrow. Different routes of entry were also proposed: one through the mesenchyme and the other via the blood circulation

[43][45]. Alliot et al., aiming to delineate the origin of microglia in

mice, detected these cells in the brain from Ε8 being derived from YS progenitors, which proliferate in situ

[44][46].

The YS origin of microglia was confirmed by Ginhoux et al. by performing a fate mapping analysis in

mice and showing that YS primitive myeloid progenitors generated before E7.5 can contribute to the CNS microglial population

[45][47]. Moreover, in this study, RUNX1

+ YS progenitors were found to migrate into the brain through blood vessels between E8.5 and E9.5

[45][47]. The YS origin was further supported by identifying the transcription factor MYB, which is required for the development of HSCs as well as CD11b

high monocytes and macrophages

[46][48], contrary to YS-derived macrophages, which are the potential precursors of CNS microglia

[47][49]. Specifically, primitive c-kit

+ EMPs detected from E8 in the YS were proposed to serve as the precursors of microglia in

mice [48][50]. As the progenitors of microglia were identified to be the EMPs of YS, the vast majority of other tissue-resident macrophages arise from fetal monocytes that derive from late c-MYB

+ EMPs of the YS

[49][51]. The HSC-derived hematopoiesis that takes place for monocytes at E14.5 and granulocytes at E16.5 in

mice advocates that these progenitors only seldom replace parenchymal microglia, which mainly emanates from CSF-1R

+ EMPs.

[50][52]. This view was re-evaluated by Sheng et al., who developed the Kit

MercreMer fate mapping

mouse strain and suggested that all resident-tissue macrophages, except microglia and Langerhans cells of the epidermis, are derived from HSCs

[51][53].

In 2018, De et al. identified two distinct microglial cell populations, namely canonical (non-HOXB8) and HOXB8 microglia using a transgenic strategy, fluorescence-activated cell sorting technique in YS and qRT-PCR in HOXB8 cells in the different hematopoietic tissues

[52][54]. The HOXB8 population was suggested to be derived from the second wave of YS hematopoiesis populating the AGM and fetal liver. Besides the YS, an additional source of microglia was proposed by Fehrenbach et al., who considered the definitive hemopoiesis as responsible for microglial development and recruitment to the

mouse CNS, especially at the post-YS phase

[53][55]. Besides parenchymal microglia, a genetic distinct population of macrophages was identified, namely the border-associated macrophages (BAMs) residing among the meninges, choroid plexus, and perivascular spaces. Like microglia, these cells are generated by early EMPs; however, microglia require TGF-β for their development, whereas BAMs are TGF-β-independent. Additionally, in the

mouse YS, two distinctive primitive populations were observed: the CD206

− and CD206

+ macrophages. The differentiation of these populations after their final colonization is mediated by environmental drivers

[54][56]. Interestingly, tamoxifen dosing in CCR2-CreER transgenic

mice suggested that not only YS EMPs, but also fetal HSC-derived monocytes participate in the generation of IBA1

+TMEM119

+P2RY12

+ parenchymal microglia, IBA1

+, and isolectin

+ BAMs in the

mouse brain

[55][57]. Lastly, a recent study in eight aborted

human embryos proposed that tissue-resident macrophages development is very similar to other mammalian species, highlighting the presence of two distinct waves of YS-derived macrophages. Specifically for microglia, they were found to be derived from the early first wave along with a minor contribution from the second one

[56][58].

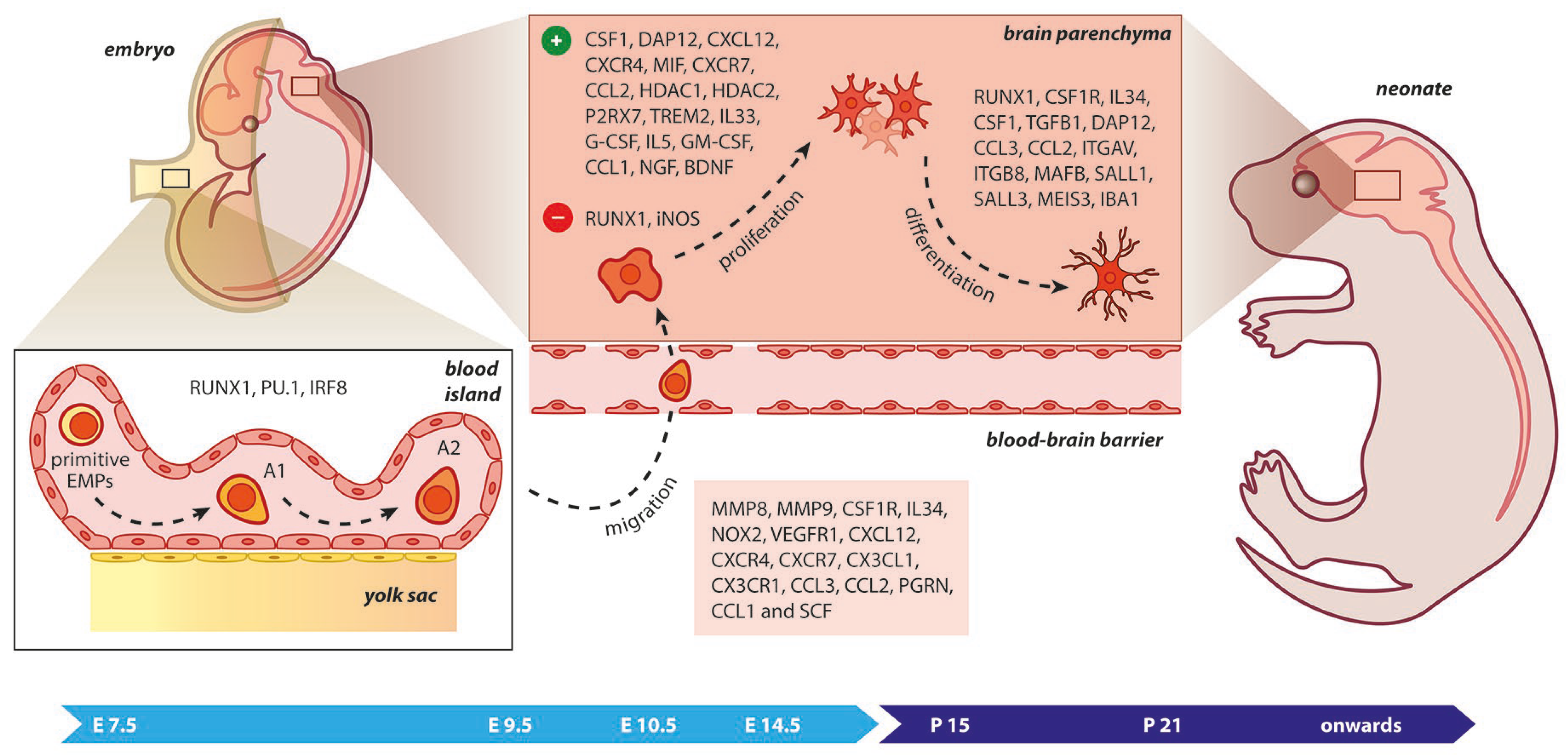

3. Molecular Cues Orchestrating Microgliogenesis

Upon birth, the phenotype of microglia corresponds to an amoeboid shape, phagocytically and mitotically active, while in later developmental stages, microglia become ramified. The RUNX1, a transcription factor expressed during the first two postnatal weeks at the forebrain by amoeboid microglia, downregulates the proliferation of these cells and assists in their transformation towards a ramified morphology

[57][59]. During embryonic development, RUNX1 controls the expression of the transcription factor PU.1

[58][60]. In

Irf8-deficient YS, the number of A1 cells (CD45

+ c-kit

lo CX

3CR1

− immature cells) remained unchanged, while the A2 population (CD45

+ c-kit

− CX

3CR1

+ cells) decreased

[48][50]. Additionally,

Pu.1 deficiency provoked an impairment of A1 and A2 progenitors. From A2 cells, microglia were generated and expanded in the developing brain under the influence of specific matrix metalloproteinases, such as MMP-9 and MMP-8. Factors such as MYB, BATF3, ID2, Klf4, and NR4A1 were not necessary for the development of microglia from their progenitors

[48][59][50,61]. While PU.1 was essential for terminal myeloid differentiation, early myeloid genes such as

Gm-csfr,

G-csfr, and

Mpo were maintained in

Pu.1-/- embryos, whereas myeloid genes associated with terminal differentiation (etc

. Cd11b,

Cd64, and

M-csfr) were found to be impaired

[60][62].

The CSF-1R is a vital receptor for microglial cell development expressed on YS macrophages and microglia at E9.5 and throughout brain development. In contrast to many tissue macrophages, adult microglia can still be replenished, albeit at reduced levels in

Csf-1op/op mice. Although the microglia presented—even in small amounts—in a null mutation model of the

Csf-1 in

Csf-1op/op mice, microglia were fully depleted in

mice lacking CSF-1R

[45][47]. This was a strong clue that a second ligand of CSF-1R, namely the IL-34, was implicated in microgliogenesis. As the microglial phenotype in

Csf-1r-/- mice was more severe than that observed in

Csf-1op/op mice, it was evident that IL-34 plays a significant role in the regulation of microglial homeostasis. Its mRNA expression in the brain is also significantly higher than that of CSF-1 during early postnatal development

[45][47]. In addition, in

il-34- and

csf-1ra-deficient

zebrafish larva, the migration and colonization of CNS by embryonic macrophages was impaired, indicating a role for the Il34-Csf1ra pathway during microglial cell expansion throughout the CNS

[61][63].

Figure 2. Microgliogenesis at a glance. The primitive erythro-myeloid progenitors (EMPs; early, c−MYB−independent, CSF−1R+ EMPs) arise from the yolk sac (YS) as early as embryonic day 7.5 (E7.5). These cells give rise to CD45+ c−kitlo CX3CR1− immature (A1) cells that develop into CD45+ c−kit− CX3CR1+ (A2) cells. The early differentiation of microglial progenitors is regulated by the expression of RUNX1, PU.1, and IRF8. The invasion of progenitors into the neural tube begins at E9.5 through blood circulation and is followed by proliferation and terminal differentiation. As the blood–brain barrier becomes impermeable to small molecules at E14.5, the microglia invasion may be prevented. The transformation of immature microglia into ramified (mature form) occurs between the second and third postnatal weeks. The migration, proliferation, and terminal differentiation of microglia are also orchestrated from the depicted molecular cues. Light blue arrow timeline represents prenatal period, dark blue arrow timeline refers to postnatal days.

The depletion of

Cxcl12 seems to block microglial cell invasion into the SVZ, whereas the ectopic

Cxcl12 expression or pharmacological impairment of CXCR4 demonstrated that the CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling is involved in microglial cell recruitment assisting cortical development. In the same context, cell death occurring in the developing forebrain stimulates microglial cell proliferation mediated via MIF activation

[68][70]. Treatment with CXCL12 activates Erk1/2 and Akt signaling, which are necessary for microglial proliferation mediated by CXCL12. Similarly, Erk1/2 signaling was found to be important for CXCL12-depedent migration of microglial populations. Pharmacological blockade of CXCR4 or CXCR7 induced a decline in CXCL12-mediated proliferation and migration of microglial cells, suggesting that CXCR4 and CXCR7 form a receptor unit for CXCL12 in the

rodent microglia required for the aforementioned developmental processes, both in vitro and in vivo

[69][71]. Furthermore, CX3CL1/CX3CR1 signaling may regulate microglial invasion within CNS parenchyma during postnatal life

[70][72]. Interestingly, the transformation of microglia from an amoeboid to a ramified morphology was proposed to be mediated by cues released from astrocytes. Utilizing time-lapse video microscopy in co-cultures of

human fetal microglial cells and astrocytic cells, the chemokines MIP-1α and MCP-1 were identified as regulators of microglial motility and differentiation

[71][73].

The overexpression of

miR-124 in microglia accelerated the transformation of these cells to an inactivated state through inhibition of the C/EBP-α and PU.1, while the depletion of

miR-124 led to microglial activation both in vitro and in vivo. These findings underscored the potential role of

miR-124 as a regulator of microglial surveillance in the CNS

[72][74]. Microglial polarization is regulated by ARID1A, an epigenetic subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex, through alterations of the chromatin state in microglia

[73][74][75,76]. The migration of microglial cells also seemed to be affected by PGRN, because its knockdown resulted in a failure of microglial precursors to colonize the embryonic retina

[75][77]. The absence of integrin αVβ8 from the CNS prevents microglial transition from immature precursors to a mature state. As αVβ8 controls TGFβ signaling to microglia, these “dysmature” microglial populations are expanded as a consequence of impaired TGFβ signaling during the perinatal period, leading to disrupted oligodendrocyte development, interneuron loss, and neuromotor dysfunction

[76][78]. Epigenetic factors may also affect microglial development. Embryonic HDAC1 and HDAC2 absence disrupts microgliogenesis, altering the crucial acetylation marks implicated in morphology, reactivity, cell cycle, and apoptosis. Specifically, reduced proliferation and induced apoptosis were observed after ablation of the above epigenetic regulators, resulting in the hyperacetylation of specific pro-apoptotic and cell cycle genes

[77][79].

Fate-mapping strategies remain the best way to track cells from the embryonic YS (microglia) versus bone-marrow (monocyte-derived macrophages). In terms of markers, the exact distinction between microglia and periphery-originated macrophages is challenging as they express common markers such as CD11b, CX3CR1, CD45, F4/80, and IBA-1

[78][80]. Nevertheless, TMEM119 has been recognized as a trans-membranous molecule that is abundantly produced only by microglia, along with P2RY12, but both markers can be downregulated in disease

[5][79][80][5,81,82]. However, recently it was proposed that TMEM119 is neither a specific nor a reliable marker for microglial cells

[81][83]. Siglec-H was also found to be a specific marker for microglia in

rodents, as it was almost absent in CNS-infiltrating monocytes and CNS-associated macrophages

[82][84].

TREM2, as a protein involved in intracellular signals, interacts with transmembrane protein DAP12, thus activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and stabilizing β-catenin via blocking GSK3β activation. Thus, TREM2 promotes the survival and proliferation of primary microglial cells

[83][88]. In addition, the transcription factor MAFB may be involved in regulating microglial cell development and homeostasis

[84][89]. The homeostasis is further preserved by the epigenetic regulator MECP2, which controls microglial responsiveness to external stimuli

[85][86][90,91]. In the postnatal developing brain, the absence of microglial EED, a Polycomb protein vital for synaptic pruning, led to the upregulation of phagocytosis-related genes

[87][92]. Contrariwise, the deletion of microglial

Tgm2 in

mice resulted in the downregulation of microglial phagocytic-related genes accompanied by synaptic pruning and cognitive impairment

[88][93]. A P2RX7-induced proliferation of embryonic spinal cord microglia was proposed after comparison of wild-type and

P2rx7-/- embryos. The ablation of

P2rx7 also affected microglial density, while

Pannexin-1-/- embryos showed unaltered proliferation rates. Altogether, microglial proliferation may be regulated by P2RX7 receptors in a Pannexin-1-independent way during early development

[89][94].

Another in vitro study confirmed that IL-33, which is released by astrocytes and endothelial cells, enhances the proliferation of microglial populations

[90][95]. Similarly, in the uninjured CNS, G-CSF increased microglial numbers

[91][96]. However, the GM-CSF was a stronger stimulus for microglial proliferation in

human brain cultures

[92][97]. The increasing microglial populations were correlated with a direct effect of GM-CSF upon treatment with IL-5, whereas IL-5 induced an intense cellular metabolism in contrast with GM-CSF treatment in microglial cell cultures

[93][98]. Moreover, 1 ng/mL of CCL-1 mediated chemotaxis, while 100 ng/mL increased motility, proliferation, and phagocytosis of microglial cells in culture

[94][99]. An induction of microglial cell proliferation was mediated in vitro by CCL2 along with

miR-10 [95][100]. Neurotrophins have a potential role in modulating the proliferation and survival of microglial populations in vitro. Specifically, NGF and BDNF increased microglial proliferation, contrary to NT-3 and NT-4

[96][101]. Lastly, SCF was identified as a promoter of microglial cell proliferation, migration, and phagocytosis in culture (

Table 1)

[97][102].

Table 1. Molecular drivers of microglial early differentiation, migration, proliferation, and terminal differentiation.

| Gene |

Locus |

Protein |

Species |

Biological Role |

Ref. |

| BDNF |

11p14.1 |

Brain derived neurotrophic factor |

Mice |

Proliferation |

[96][101] |

| CCL1 |

17q12 |

C-C motif chemokine ligand 1 |

Mice |

Migration; Proliferation |

[94][99] |

| CCL2 |

17q12 |

C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 |

Human; Mice |

Migration; Proliferation; Terminal differentiation |

[71][95][73,100] |

| CCL3 |

17q12 |

C-C motif chemokine ligand 3 |

Human |

Migration; Terminal differentiation |

[71][73] |

| CSF1 |

1p13.3 |

Colony stimulating factor 1 |

Mice |

Proliferation; Terminal differentiation |

[45][66][47,68] |

| CSF1R |

5q32 |

Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor |

Mice; Zebrafish |

Migration; Terminal differentiation |

[45][61][47,63] |

| CX3CL1 |

16q21 |

C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1 |

Mice |

Migration |

[70][72] |

| CX3CR1 |

3p22.2 |

C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1 |

Mice |

Migration |

[70][72] |

| CXCL12 |

10q11.21 |

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 |

Mice; Rat |

Migration; Proliferation |

[68][69][70,71] |

| CXCR4 |

2q22.1 |

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 |

Mice; Rat |

Migration; Proliferation |

[68][69][70,71] |

| CXCR7 |

2q37.3 |

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 7 |

Rat |

Migration; Proliferation |

[69][71] |

| DAP12 |

19q13.12 |

DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa |

Mice |

Proliferation; Terminal differentiation |

[65][67[66],68] |

| G-CSF |

17q21.1 |

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor |

Mice |

Proliferation |

[91][96] |

| GM-CSF |

5q31.1 |

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

Human |

Proliferation |

[92][97] |

| HDAC1 |

1p35.2–p35.1 |

Histone deacetylase 1 |

Mice |

Proliferation |

[77][79] |

| HDAC2 |

6q21 |

Histone deacetylase 2 |

Mice |

Proliferation |

[77][79] |

| IBA1 |

6p21.33 |

Ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 |

Mice |

Terminal differentiation |

[98][104] |

| IL33 |

9p24.1 |

Interleukin 33 |

Mice |

Proliferation |

[90][95] |

| IL34 |

16q22.1 |

Interleukin 34 |

Mice; Zebrafish |

Migration; Terminal differentiation |

[45][61][47,63] |

| IL5 |

5q31.1 |

Interleukin 5 |

Rat |

Proliferation |

[93][98] |

| INOS |

19p13.11 |

Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

Mice |

Proliferation |

[99][105] |

| IRF8 |

16q24.1 |

Interferon regulatory factor 8 |

Mice |

Early differentiation |

[48][50] |

| ITGAV |

2q32.1 |

Integrin subunit alpha V |

Mice |

Terminal differentiation |

[76][78] |

| ITGB8 |

7p21.1 |

Integrin subunit beta 8 |

Mice |

Terminal differentiation |

[76][78] |

| MAFB |

20q12 |

MAF bZIP transcription factor B |

Mice |

Terminal differentiation |

[84][89] |

| MEIS3 |

19q13.32 |

Meis homeobox 3 |

Mice |

Terminal differentiation |

[64][66] |

| MIF |

22q11.23 |

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor |

Mice |

Proliferation |

[68][70] |

| MMP8 |

11q22.2 |

Matrix metallopeptidase 8 |

Mice |

Migration |

[48][50] |

| MMP9 |

20q13.12 |

Matrix metallopeptidase 9 |

Mice |

Migration |

[48][50] |

| NGF |

1p13.2 |

Nerve growth factor |

Mice |

Proliferation |

[96][101] |

| NOX2 |

Xp21.1-p11.4 |

NADPH oxidase 2 |

Mice |

Migration |

[67][69] |

| P2RX7 |

12q24.31 |

Purinergic receptor P2X 7 |

Mice |

Proliferation |

[89][94] |

| PGRN |

17q21.31 |

Progranulin |

Zebrafish |

Migration |

[75][77] |

| RUNX1 |

21q22.12 |

RUNX family transcription factor 1 |

Mice |

Proliferation; Early and terminal differentiation |

[57][58][59,60] |

| SALL1 |

16q12.1 |

Spalt like transcription factor 1 |

Mice |

Terminal differentiation |

[64][66] |

| SALL3 |

18q23 |

Spalt like transcription factor 3 |

Mice |

Terminal differentiation |

[64][66] |

| SCF |

12q21.32 |

Stem cell factor |

Mice |

Migration; Proliferation |

[97][102] |

| SPI1 |

11p11.2 |

Transcription factor PU.1 |

Mice |

Early differentiation |

[48][50] |

| TGFB1 |

19q13.2 |

Transforming growth factor beta 1 |

Mice |

Terminal differentiation |

[63][65] |

| TREM2 |

6p21.1 |

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 |

Mice |

Proliferation |

[83][88] |

| VEGFR1 |

13q12.3 |

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 |

Mice |

Migration |

[67][69] |

4. Proliferation in the Adult Compromised CNS

As the BBB and microglial cell maturation are established, the question arises as to how microglia are renewed in the adult brain. The participation of bone marrow-derived cells in the repopulation of microglial cell niches was proposed in various conditions, especially after bone marrow transplantation

[102][103][104][105][106][107][108,109,110,111,112,113], and in diseases such as stroke

[108][114], cerebral ischemia

[109][115], bacterial meningitis

[110][116], entorhinal cortex lesions

[111][117], Parkinson’s disease

[112][118], Alzheimer’s disease

[113][114][119,120], multiple sclerosis

[115][121], facial nerve axotomy and autoimmune encephalitis

[116][122], scrapie

[117][123], and brain and peripheral nerve injury

[118][119][120][124,125,126]. During aging and the transition from plasticity to proinflammatory activation in primary neurodegeneration, the latest data also suggest that many metabolic byproducts and mitochondrial components can serve as damage-associated molecules, creating an extracellular gradient and accumulation of reactive oxygen species, which in turn propagate the inflammatory neurodegeneration

[121][122][127,128]. Under acute situations such as when a stab wound inflicts damage to a brain region, the resident microglia need the contribution of circulating monocytes to efficiently respond to the extra load of detritus

[123][129]. It has been suggested that even after recovering from severe brain inflammation, resident microglia form a remarkably stable cell pool that is seldom replenished by hematogenous cells in adult animals

[124][130].

A physiological process that aids in the development of the adult microglial cell population is the proliferation of microglial precursors in the developing brain

[125][131]. Lawson et al. suggested that resident microglia synthesize DNA and go on to divide in situ. Additionally, cells were found to be recruited from the circulating monocyte pool through an intact BBB and rapidly differentiated into resident microglia. These two processes contributed almost equally to the steady-state turnover of resident microglia

[126][132]. In a

mouse model of ALS, the local proliferation of resident microglia had the greatest contribution to the observing microgliosis, while the effects of bone marrow-derived cells were limited among the microglia populations

[127][133]. Strong evidence for the local self-renewal of CNS microglia as the main source of repopulation of adult microglia were obtained from a model using chimeric animals obtained by parabiosis showing that these cells could be maintained independently from bone marrow–derived cells during adulthood in ALS and facial nerve axotomy

[128][134]. However, Ly-6C

hiCCR2

+ monocytes were found to be recruited to the lesioned brain differentiating into mature microglia. Remarkably, monocyte invasion during CNS pathology with an intact BBB or in non-diseased adult CNS required previous conditioning of brains, such as direct tissue irradiation

[129][135]. Indeed, brain conditioning with lethal irradiation and alkylating agents such as busulfan was found to be vital for an efficient microglial cell repopulation after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

[130][136].

In 2013, Li et al. observed that after ischemic stroke, a small number of blood-derived CX3CR1

GFP/+ cells invaded the brain parenchyma; however, these cells were phenotypically different from resident microglia with distinct kinetics. This study delineated the greatest impact of local resident microglia on the repopulation of parenchymal cells compared to recruited blood-derived cells after ischemic stroke

[131][137]. The efficiency of microglia for self-renewal arising from a CNS-resident pool independently from peripheral myeloid cells was also supported by another experimental study that investigated the repopulation of brain parenchyma using a model of conditional depletion of microglial cells

[132][138]. During the process of cellular restoration, the proliferation of local microglia was found to be dependent on the IL-1 receptor, which was highly expressed by local cell pools. Bone-marrow-derived macrophages populated the brain only after irradiation and bone marrow transplantation, and did not express the IL-1 receptor

[132][138].

In

zebrafish, using temporal-spatial resolution fate mapping analysis, embryonic microglia emerged from the rostral blood island in a RUNX1-independent and PU.1-dependent manner, while adult microglia originated from the ventral wall of the dorsal aorta in a RUNX1-dependent, c-MYB- and PU.1-independent manner

[133][139]. The microglial self-renewal was shown to resemble a stochastic process at steady state, whereas clonal microglial expansion seems to predominate under unilateral facial nerve axotomy

[134][140]. In another study, the partial microglial depletion resulted in the engraftment of peripherally derived macrophages independently of irradiation. These newly-engrafted cell populations differ transcriptionally from microglia

[135][141]. Similarly, another depletion study showed that the microglial niche is filled with new cells via local proliferation of CX3CR1

+F4/80

lowClec12a

– microglia and invasion of CX3CR1

+F4/80

hiClec12a

+ macrophages derived from Ly6C

hi monocytes. This engraftment was associated with vascular activation and type I interferon, while it was shown to be independent of BBB integrity

[136][142]. These peripherally engrafted cells were transcriptionally distinct from microglia, showcasing different surface marker expression, phagocytic capacity, and cytokine release

[136][137][142,143].

Through additional studies, Huang et al. delineated that repopulated microglial cell populations are entirely generated from residual microglial proliferation after acute depletion

[138][144], instead of nestin-expressing progenitors, as was argued in a CSF1R inhibitor-mediated experiment

[139][145]. In agreement with the previous statement, Zhan et al. demonstrated that after acute ablation, the newborn adult microglia generated via self-renewal from the local CX3CR1

+ microglia without any contribution of nestin

+ progenitors or peripheral myeloid cells. The repopulated microglia formed stable and distinct clusters with minimum migration capacity via clonal expansion. Although these regenerated microglial cells were presented in an immature state, microglial differentiation was mediated by NF-κB and interferon pathways

[140][146]. A fate mapping study from Chen et al. showed that after neonatal stroke, a monocyte-to-microglia transition is possible

[55][57]. In contrast, a study conducted in 2021 showed that microglia are not replaced by bone-marrow-derived cells in Alzheimer’s disease similar to the BAMs, which seldom replenished the microglial cell pool

[141][147]. Ultimately, microglial cell manipulation is being intensely investigated in the context of immune-mediated diseases such as multiple sclerosis, where microglia are heavily implicated as pathogenic mediators of progressive disease

[142][143][144][148,149,150], and targeted therapies are being developed

[145][146][151,152].