You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Alfred Zheng and Version 3 by Alfred Zheng.

Engineered nanoparticles (NPs) with pharmacological potential can be rapidly taken up by a variety of cell types and have the potential to traverse intracellular and intercellular barriers. NPs can trigger the production of reactive oxygen species, activate the complement system, or impair the functionality of membranes and cellular barriers, depending on the kind, dose, and incubation period. These acts cause immediate or persistent damage to the organism, which can result in catastrophic consequences such as inflammation, gene mutations, and severe organ damage.

- liposomes

- nanoparticles

- drug delivery

1. Introduction

Nanotechnology is an interdisciplinary branch that studies particles sized between 1 and 100 nanometers at least at one dimension. Nano-sized particles exhibit a high surface area-to-volume size ratio and show unique properties that enable a variety of applications in medical, engineering, agri-food, and related sectors. Moreover, the interactions of nanoparticles (NPs) with biomolecules and their behavior in cell, tissue and organism contexts has allowed the development of nanoparticle-based therapy approaches [1]. Nanomedicine aims to overcome the limits of free therapies and biological hurdles that vary across patient groups and diseases. Pharmaceutical dosage formulations based on NPs and different drugs (such as cytostatics, proteins, peptides, ARN, antibiotics, and antiviral and antiparasitic drugs) have become a high priority in pharmaceutical research. The use of lipid nanoparticles as a carrier for siRNA and mRNA in a recently approved medication and vaccine illustrates advances in the field. Novel engineered nanomaterials still hold much promise for improving disease diagnosis and specific treatment [2]. The principal advantage of NP-drug complexes is their ability to reach tissue and target organs while improving the drug’s intracellular penetration and distribution. In addition, nanodevices for drug delivery may protect a drug from degradation and allow the modification of drug pharmacokinetics.

Nanoparticles and nano-formulations may act differently from their bulk molecules and substances of the same composition. In particular, due to their small size and high surface area, NPs can be significantly more effective than conventional materials of the same composition [3]. Despite the pivotal clinical advantages, highly active NPs are likely to have negative effects. There are several approved orally given nano-formulations that may cause severe secondary effects due to their topical toxicities to the gastrointestinal system and metabolic organs, such as the liver and kidney. Due to their small size and accumulated surface charge, surface tension, and high chemical/structural complexity, nanoparticles may penetrate different organs and cell compartments [4]. Typically, nanoparticles are taken up through endocytosis by the cells in the liver, spleen, lungs and bone marrow [5]. Consequently, it is important to elucidate the fate of internalized NPs and immune responses to them because both can differ from those elicited by standard formulations containing particles of larger sizes.

2. Drug Delivery Applications

Over the past few years, studies of nano-sized drug delivery systems have become a flourishing research field, and many formulations have reached the market [6]. However, the administration of some NPs is associated with an increased risk of toxicity, requiring discontinuation of the therapy. Clinical pharmacologists make efforts to produce safe nanomedicines by combining engineered nanoparticles with precise control over their surface modifications (such as surface charge, covertness, size, shape, and targeting moieties) and other characteristics that can be screened in order to find the best formulation assuring a prolonged and tailored release with low toxicity. Moreover, the tendency is to make drug delivery systems multifunctional and programmable by external signals or the local environment, thereby transforming them into nanodevices.

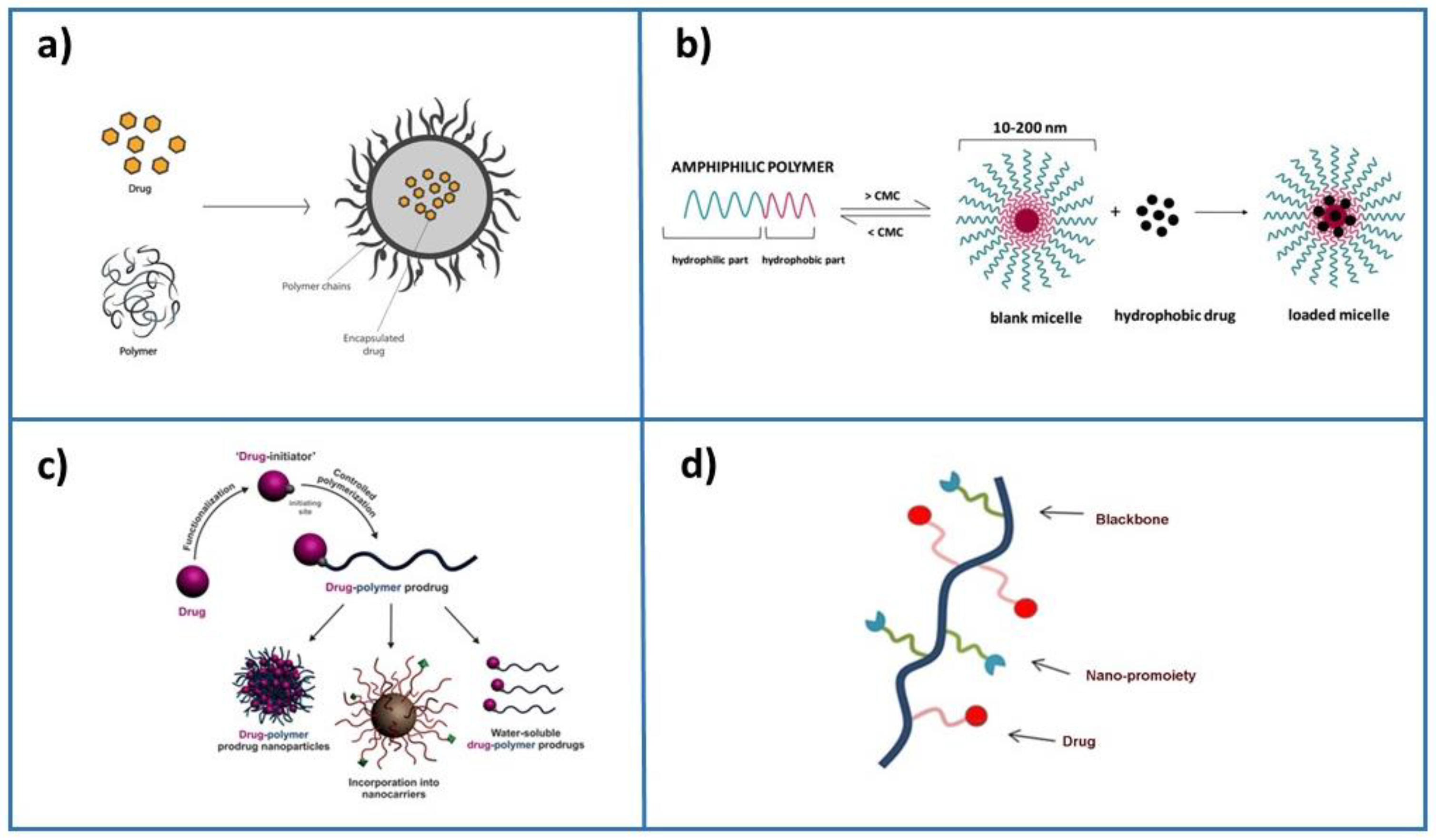

The crucial requirement of efficiently established technology is to precisely deliver drugs to diseased areas in the body together with tissue biodistribution and rapid metabolization and excretion from the body. Several methods to obtain drug delivery systems have been developed: (i) drug physical encapsulation into biocompatible nanoparticle assemblies during the formulation process, (ii) the self-assembly of polymers in an aqueous solution containing the drug, (iii) growing a single polymer chain from a solution containing a drug in a controlled fashion, termed “drug-initiated”, and (iv) drug conjugation with a nano-promoiety (Figure 1). Usually, the drug is inactive when conjugated but active when the nanocarrier is cleaved. This method is frequently used for liposome-based and polymer-based formulations, in which drugs are covalently bound to lipidic or polymer scaffold building blocks. The cleavage may be induced by hydrolysis, enzymatic reactions, or reduction, and the active drug is realized from the polymer. However, although simple synthetic methods for producing nanoparticle-based emulsions are highly desired, the development of nanocarriers often requires a series of synthetic steps to ensure stability and protection and decrease toxicity. An emerging approach is based on paramagnetic nanoparticles enabling the remote directing and management of the drug delivery operations, such as driving magnetic nanoparticles to the tumor and then either releasing the drug load or just heating them to destroy the surrounding tissue [7][8][9].

Figure 1.

Principal formulation methods for drug encapsulation: (

a

) drug physical encapsulation (adapted with permission from

[10]

), (

b

) self-assembly of polymers and drug (adapted from

[11]

), (

c

) drug-initiated method (adapted from

[6]

), and (

d

) drug conjugation with a nano-promoiety.

Examples of nanocarriers that have gained traction in the pharmaceutical industry are liposomes or lipid-based nanoparticles. Lipid nanoparticles, in particular, have undergone extensive research and have effectively accessed the clinical field for the delivery of small molecules, siRNA medicines, and messenger RNA (mRNA) [12][13]. Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are used to mediate gene silencing in cells, and RNA interference (RNAi) is an emerging cancer therapeutic method [14]. To obtain the efficient distribution of siRNAs into cells in vivo, including tumor and/or host cells in the tumor microenvironment, successful RNAi-mediated gene silencing requires overcoming numerous physiological barriers. Lipid-based nanoparticle siRNA delivery techniques allow for overcoming these physiological hurdles. Because of their significant negative charge, siRNAs can be integrated into NP formulations via covalent connections with lipid components or electrostatic interactions with the liposome surface [15]. Another example is the encapsulation of mRNA, which is a new type of therapeutic agent that can be used to prevent and treat a variety of ailments. To be functional in vivo, mRNA requires delivery mechanisms that are safe, effective, and stable, as well as systems that allow for cellular uptake and mRNA release [13]. Lipid nanoparticle–mRNA vaccines have started to be in clinical use against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which really is a major step forward for mRNA therapies [16]. Protein replacement therapies, viral vaccines, cancer immunotherapies, cellular reprogramming, and genome editing are just a few of the instances where mRNA has demonstrated therapeutic potential, attracting the interest of formulation scientists due to its low toxicity, excellent drug solubility, substance release, and precise targeting.

3. Biological Barriers in Drug Delivery Therapy

The delivery of medications to a target place typically entails traversing biological barriers. Biological barriers keep organs and tissues safe from physical, chemical, and biological injury while also maintaining tissue homeostasis [17]. The biological barriers also serve as key interfaces among organs and their exterior, such as body fluids. Endothelial or epithelial cell layers are the fundamental components of biological barriers [18]. The barriers are semi-permeable since they keep extraneous material out of the tissue while allowing small molecules of specific characteristics to pass through. Consequently, tissue-specific nanocarriers that can cross the biological barrier due to their small sizes, morphology, and surface chemistry can transport bigger molecules [17]. Biological barriers could be a direct target for treatment techniques [19] when NPs are used to disturb and weaken the barrier in order to increase its permeability. The paracellular barrier, efflux of molecules, the metabolic barrier, signaling between the body fluid and the tissue, and waste clearance from the tissues are all affected by these functional changes. The features of biological barriers constitute both a difficulty in drug delivery and an opportunity for developing custom medication delivery systems that effectively reach the target region. The dynamics of NP fluid in blood vessels depend on particles’ size, surface charge, rigidity, and structural topography. By designing the physicochemical properties of an NP, its biodistribution and half-life can be improved. Most formulations have been developed for intravenous drug administration. The surface charge has been shown to crucially affect the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of nanoparticles in blood vessels through its role in protein adsorption. Highly positively charged nanoparticles are usually more rapidly cleared from circulation than highly negatively charged nanoparticles. In contrast, neutral, slightly positive and slightly negative NPs may circulate in blood with prolonged half-lives [20].

The functionality of biological barriers is known to be affected by various disorders. It is worth noting that biological barriers are dynamic systems and that small perturbations in their microenvironments may induce changes. The biological barriers, such as crossing epithelial barriers, intracellular delivery, navigating tumor micro-environments, and targeting immune cells, can be overcome by the nanoparticles used as the carrier to reach the targeted site [21]. Modifications in dynamic barrier properties are sometimes difficult to predict. This may represent a challenge for drug delivery development because the irreversible manipulation of biological systems can cause severe side effects [22]. However, this specific dynamic also presents an opportunity for the nanocarrier-based manipulation of biological barriers and facilitation of drug delivery.

4. Nanoparticle Toxicity

The physical and chemical features of NPs, such as their size, shape, surface charge, chemical compositions of the core and shell, morphology, and stability, can influence their toxicity. Among them, size and shape seem to be crucial factors that influence the particles’ interaction with living systems. Understanding the mechanism of nanoparticle toxicity provides a basis to redesign them and reduce the side effects of nano-formulations. The redesign has to take into account both the decline of the major mode of toxicity and the need to preserve the nanomaterial’s ability to perform its activity in its intended application.

4.1. Nanoparticle Size, Surface Area and Toxicity

The size of the NPs has a significant impact on their interactions with the transport and defense systems of cells and the body and thus plays a central role in determining particle activity in biomedical applications. In the case of inorganic NPs, their chemical properties and solubility are size-dependent. Colloidal solutions can be prepared with particles with diameters up to 100–200 nm under conditions where larger nanoparticles of the same material usually precipitate. As mentioned above, to assess certain biological barriers and compartments, small sizes are needed. The size restrictions may come from steric effects or specific biological functions [23]. Although decreasing the nanocarrier’s size offers many advantages, it can also enhance its toxicity. The in vivo evaluation of subcellular location, tissue distribution, and toxicity of gold NPs in rats has shown that small particles (10 and 30 nm) crossed the cell membrane and membrane of the nucleus and damaged DNA, but particles of 60 nm did not have this effect [24]. In addition, it was shown that gold NPs of 10 and 30 nm highly accumulated in the liver, kidney, and intestine, while the highest accumulation of 60 nm gold NPs was observed in the spleen.

The increased specific surface area ensures that NPs adhere efficiently to the cell and tissue surfaces. Particles smaller than 100 nm were efficiently adsorbed on the erythrocyte surface without causing cell death or morphological abnormalities, whereas particles larger than 600 nm distorted the membrane and entered the cells, causing erythrocyte death [25]. In some cases, engineered NPs with a high surface area and reactivity can generate a high level of reactive oxygen species, even intracellular ROS, thus leading to cytotoxicity and genotoxicity [26].

4.2. Nanoparticle Shape and Toxicity

Nanomaterials can be classified regarding their shape as 0D (spherical particles such as carbon and quantum dots or nanoparticles), 1D (materials with one dimension < 100 nm, such as nanowires, nanotubes, and nanorods), 2D (materials with two dimensions < 100 nm, such as nanodisks and nanosheets) and 3D (material with three dimensions < 100 nm, such as nanoflowers, nanoballs, and nanocones) [27]. Among nanomaterial spheres, ellipsoids, cylinders, sheets, cubes, and rods are the most common shapes. Their toxicity is highly influenced by their form. For instance, when the effect of needle-like, plate-like, rod-like, and spherical hydroxyapatite NPs was tested on grown BEAS-2B cells, it was found that plate-like and needle-like NPs killed a higher percentage of cells than spherical and rod-like NPs [28].

4.3. Nanoparticle Chemical Composition and Toxicity

Although the size and shape of NPs have a substantial influence on their toxicity, other aspects, such as the NP’s chemical composition and crystal structure, should not be overlooked. It has been demonstrated that NPs can degrade, and the extent of this degradation is dependent on environmental factors such as pH and ionic strength [26]. The most prevalent cause of NPs interacting with cells becoming hazardous is metal ion leakage from the NP core. Toxicity is also affected by the NPs’ core makeup. Some metal ions, such as Ag+ and Cd2+, are intrinsically poisonous, and their liberation induces cell damage. Other metal ions, such as Fe3+/4+, Mg2+, and Zn2+, are essential oligo-elements and therapeutically helpful, but in a high amount, can impair cellular processes, resulting in significant toxicity [29]. This effect can be reduced by replacing toxic species with less toxic substances that have similar properties or wrapping NP cores with robust polymer shells, silica layers, or gold shells instead of weak ligands. The chemical stabilization of the nanomaterials may prevent degradation and metal ion leakage into the body. The constitution of the core, on the other hand, might be changed by doping with different metals. For instance, the utilization of TiO2 has raised concerns about its toxicity, and the European Union banned its use at the beginning of 2022. Recent research focused on iron titanate (Fe2TiO5) nanoparticles presented as a possible biocompatible alternative to TiO2 [30]. Fe2TiO5 NPs of an average particle size of 44 nm and rhombohedral morphology caused no cell damage to human Caco-2 epithelial cells, as demonstrated by acridine orange cell staining followed by flow cytometry analysis. Alternatively, a chelating agent can be administrated together with the active nanomaterial or functionalized onto its surface to prevent toxic metal migration into the body. Finally, the morphology of the nanoparticle can be designed to minimize surface area and thus minimize dissolution [31].

4.4. Nanoparticle Surface Charge and Toxicity

Because the interactions of NPs with biological systems are largely determined by their surface charge, the surface charge of NPs plays an important role in their toxicity. The capacity of positively charged NPs to easily enter cells, as opposed to negatively charged and neutral NPs, explains their greater toxicity [32]. Positively charged NPs have a greater ability to opsonize or adsorb proteins that aid phagocytosis, such as antibodies and complement components, from blood and biological fluids. To modify the surface charge of nanomaterials, they can be produced by synthetic routes that generate a negative surface charge or can be designed to carry ligands such as polyethylene glycol that reduce protein binding. In turn, such modifications in surface properties may discourage particles from binding to cell surfaces and allow them to be controlled in terms of localization, which is highly important in the development of effective methods for delivering therapeutic medications to targets.

To reduce the production of reactive oxygen species, the band gap of the material can be tuned either by using different elements or by doping, a shell layer can be added to inhibit direct contact with the core, or antioxidant molecules can be tethered to the nanoparticle surface. When redesigning nanoparticles, it will be important to test that the redesign strategy actually reduces toxicity to organisms from the relevant environmental compartments. It is also necessary to confirm that the nanomaterial still demonstrates the critical physicochemical properties that inspired its inclusion in a product or device.

The use of microorganisms or plant extracts to synthesize nanoparticles allows for obtaining nanoparticles with high biocompatibility. Recent research showed that nanoparticles synthesized by such green synthesis methods have surfaces coated with proteins, fibers, and carbohydrates that provide them greater biocompatibility than those of the same size and shape but synthesized using chemical methods [33][34].

References

- Teixeira, M.C.; Carbone, C.; Sousa, M.C.; Espina, M.; Garcia, M.L.; Sanchez-Lopez, E.; Souto, E.B. Nanomedicines for the Delivery of Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs). Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 560.

- van der Meel, R.; Chen, S.; Zaifman, J.; Kulkarni, J.A.; Zhang, X.R.S.; Tam, Y.K.; Bally, M.B.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Ciufolini, M.A.; Cullis, P.R.; et al. Modular Lipid Nanoparticle Platform Technology for siRNA and Lipophilic Prodrug Delivery. Small 2021, 17, e2103025.

- Chenthamara, D.; Subramaniam, S.; Ramakrishnan, S.G.; Krishnaswamy, S.; Essa, M.M.; Lin, F.-H.; Qoronfleh, M.W. Therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticles and routes of administration. Biomater. Res. 2019, 23, 20.

- Reinholz, J.; Landfester, K.; Mailänder, V. The challenges of oral drug delivery via nanocarriers. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 1694–1705.

- Pallotta, A.; Clarot, I.; Sobocinski, J.; Fattal, E.; Boudier, A. Nanotechnologies for medical devices: Potentialities and risks. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2018, 2, 1–13.

- Nicolas, J. Drug-initiated synthesis of polymer prodrugs: Combining simplicity and efficacy in drug delivery. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 1591–1606.

- Patra, J.K.; Das, G.; Fraceto, L.F.; Campos, E.V.R.; Rodriguez-Torres, M.d.P.; Acosta-Torres, L.S.; Diaz-Torres, L.A.; Grillo, R.; Swamy, M.K.; Sharma, S.; et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: Recent developments and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16, 71.

- Salata, O.V. Applications of nanoparticles in biology and medicine. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2004, 2, 3.

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 908–931.

- Rivas, C.J.M.; Tarhini, M.; Badri, W.; Miladi, K.; Greige-Gerges, H.; Nazari, Q.A.; Rodríguez, S.A.G.; Román, R.Á.; Fessi, H.; Elaissari, A. Nanoprecipitation process: From encapsulation to drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 532, 66–81.

- Ghezzi, M.; Pescina, S.; Padula, C.; Santi, P.; Del Favero, E.; Cantù, L.; Nicoli, S. Polymeric micelles in drug delivery: An insight of the techniques for their characterization and assessment in biorelevant conditions. J. Control. Release 2021, 332, 312–336.

- Ball, R.L.; Hajj, K.A.; Vizelman, J.; Bajaj, P.; Whitehead, K.A. Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations for Enhanced Co-Delivery of siRNA and mRNA. Available online: https://mrna.creative-biolabs.com/lipid-nanoparticle.htm?gclid=Cj0KCQjwpImTBhCmARIsAKr58czXDK4SIH9Sd_hmQVeGsuN_L4mtk3FcKV0xjxZkbTwDbzeE7cQKG1IaArxGEALw_wcB (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Hou, X.; Zaks, T.; Langer, R.; Dong, Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 1078–1094.

- Shepherd, S.J.; Warzecha, C.C.; Yadavali, S.; El-Mayta, R.; Alameh, M.G.; Wang, L.; Weissman, D.; Wilson, J.M.; Issadore, D.; Mitchell, M.J. Scalable mRNA and siRNA Lipid Nanoparticle Production Using a Parallelized Microfluidic Device. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 5671–5680.

- Akinc, A.; Maier, M.A.; Manoharan, M.; Fitzgerald, K.; Jayaraman, M.; Barros, S.; Ansell, S.; Du, X.; Hope, M.J.; Madden, T.D.; et al. The Onpattro story and the clinical translation of nanomedicines containing nucleic acid-based drugs. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 1084–1087.

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 384, 403–416.

- Jensen, M.P. Biological Barriers. Available online: http://www.nanomedicine.dtu.dk/Research/Biological-barriers (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Wanat, K. Biological barriers, and the influence of protein binding on the passage of drugs across them. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 3221–3231.

- Yang, R.; Wei, T.; Goldberg, H.; Wang, W.; Cullion, K.; Kohane, D.S. Getting Drugs Across Biological Barriers. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1606596.

- Blanco, E.; Shen, H.; Ferrari, M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 941–951.

- Zhao, Z.; Ukidve, A.; Kim, J.; Mitragotri, S. Targeting Strategies for Tissue-Specific Drug Delivery. Cell 2020, 181, 151–167.

- Finbloom, J.A.; Sousa, F.; Stevens, M.M.; Desai, T.A. Engineering the drug carrier biointerface to overcome biological barriers to drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 167, 89–108.

- Dolai, J.; Mandal, K.; Jana, N.R. Nanoparticle size effects in biomedical applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 6471–6496.

- Lopez-Chaves, C.; Soto-Alvaredo, J.; Montes-Bayon, M.; Bettmer, J.; Llopis, J.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, C. Gold nanoparticles: Distribution, bioaccumulation and toxicity. In vitro and in vivo studies. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2018, 14, 1–12.

- Avsievich, T.; Popov, A.; Bykov, A.; Meglinski, I. Mutual interaction of red blood cells influenced by nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5147.

- Stankic, S.; Suman, S.; Haque, F.; Vidic, J. Pure and multi metal oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis, antibacterial and cytotoxic properties. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 14, 73.

- Bobrinetskiy, I.; Radovic, M.; Rizzotto, F.; Vizzini, P.; Jaric, S.; Pavlovic, Z.; Radonic, V.; Nikolic, M.V.; Vidic, J. Advances in nanomaterials-based electrochemical biosensors for foodborne pathogen detection. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2700.

- Sukhanova, A.; Bozrova, S.; Sokolov, P.; Berestovoy, M.; Karaulov, A.; Nabiev, I. Dependence of nanoparticle toxicity on their physical and chemical properties. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 1–21.

- Randazzo, P.; Anba-Mondoloni, J.; Aubert-Frambourg, A.; Guillot, A.; Pechoux, C.; Vidic, J.; Auger, S. Bacillus subtilis regulators MntR and Zur participate in redox cycling, antibiotic sensitivity, and cell wall plasticity. J. Bacteriol. 2020, 202, e00547-19.

- Rizzotto, F.; Vasiljevic, Z.Z.; Stanojevic, G.; Dojcinovic, M.P.; Jankovic-Castvan, I.; Vujancevic, J.D.; Tadic, N.B.; Brankovic, G.O.; Magniez, A.; Vidic, J.; et al. Antioxidant and cell-friendly Fe2TiO5 nanoparticles for food packaging application. Food Chem. 2022, 390, 133198.

- Truskewycz, A.; Yin, H.; Halberg, N.; Lai, D.T.; Ball, A.S.; Truong, V.K.; Rybicka, A.M.; Cole, I. Carbon Dot Therapeutic Platforms: Administration, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity, and Therapeutic Potential. Small 2022, 18, 2106342.

- Buchman, J.T.; Hudson-Smith, N.V.; Landy, K.M.; Haynes, C.L. Understanding nanoparticle toxicity mechanisms to inform redesign strategies to reduce environmental impact. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 1632–1642.

- Afrouz, M.; Ahmadi-Nouraldinvand, F.; Elias, S.G.; Alebrahim, M.T.; Tseng, T.M.; Zahedian, H. Green synthesis of spermine coated iron nanoparticles and its effect on biochemical properties of Rosmarinus officinalis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 775.

- Leung, H.M.; Chu, H.C.; Mao, Z.; Lo, P.K. Versatile Nanodiamond-Based Tools for Therapeutics and Bioimaging. Chem. Commun. 2023.

More