You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Rui Xue Zhang and Version 2 by Beatrix Zheng.

Posterior capsule opacification (PCO) remains the most common cause of vision loss post cataract surgery. The clinical management of PCO formation is limited to either physical impedance of residual lens epithelial cells (LECs) by implantation of specially designed intraocular lenses (IOL) or laser ablation of the opaque posterior capsular tissues; however, these strategies cannot fully eradicate PCO and are associated with other ocular complications.

- drug delivery

- PCO

- controlled release

- pharmacological agent

1. Conventional Delivery of Free Drug(s) Solution

Various mechanisms of drug action have been explored to eliminate residual LECs inside the capsular bag. These include targeting different processes of PCO development, including anti-proliferation, anti-migration, anti-adhesion and anti-metabolite [1]. The intracapsular application methods of drug delivery for these purposes include direct injection, sealed-capsule irrigation (SCI) devices, and implants (i.e., lens refilling and IOL). Table 1 [2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14] summarizes those drugs, their targeting mechanisms and administration methods in both human and preclinical PCO animal models. The literature was selected based on two criteria: (1) the drug effect was evaluated in vivo and (2) the drug dose was provided. Distilled water is considered the only clinically safe agent to cause LEC lysis (via water-mediating hypoosmotic stress). To apply intracapsular distilled water, Zhang et al. utilized a fluid-air-dropping technique for which a syringe was connected to a silicone-tipped cannula for water loading and removal. Sterile air in the capsular bag prevented exposure of adjacent tissues in the anterior chamber to distilled water, thus allowing for selective targeting of LECs [2]. Surgical complications were not observed, nor was there any apparent damage to adjacent structures [2]. It is relevant to note a human trial study of the aldose reductase inhibitor, Sorbinil. This drug was administered orally (100 or 200 mg twice daily) or topically (0.5 mg) to diabetic patients undergoing intracapsular extraction [3]. In patients, Sorbinil was transported across the aqueous humor into the lens in humans, and a later study in mice revealed Sorbinil attenuated induction of α-SMA and E-cadherin, which are critical EMT marker proteins responsible for LEC migration and EMT during PCO formation [3][4].

Direct injection of single doses of potent drugs to the anterior and posterior chamber is a common method to kill LECs after phacoemulsification. Although the effectiveness of some drugs, such as mitomycin C and 5-Fluorouracil (5-Fu), in the inhibition of LEC proliferation has been identified, dose-associated ocular toxicity, such as corneal edema, remains a critical concern [5][9]. For example, to reduce the opacification of the capsular bag that is associated with lens replacement, 5 min treatment inside of the lens capsular bag with a solution of the two anti-proliferation drugs, actinomycin D and cycloheximide, reduced the development of visible capsular opacification for three months in rabbits; however, some of the animals displayed completely opaque cornea [9]. To reduce drug exposure to healthy ocular structures, a channel device SCI is applied intraoperatively to isolate the capsular bag in situ before drug treatment [15]. Kim et al. used SCI to compare the efficacy and toxicity of intraoperatively injected antiproliferative mitomycin C (0.04 mg/mL) and distilled water in rabbits after endocapsular phacoemulsification. The drug solution and SCI device were removed 2 min after injection. Compared to those administered distilled water, rabbits treated with SCI combining mitomycin C had a smaller opacification area in the posterior capsule and showed no toxicity in the surrounding ocular tissues [8].

The utilization of ocular implants, such as IOLs and lens refilling, is an alternative method for the application of free drugs into the capsular bag. Lens refilling has demonstrated a significant reduction in the PCO process [10][11][12]. In a rhesus monkey model, actinomycin-D was delivered into the capsular bag by application of the lens-filling material sodium hyaluronate (1%) before refilling with a silicone polymer [11]. An IOL can be pre-soaked in the drug solution before implantation for use as a vehicle of drug application. For example, implantation of an IOL coated with DEX was shown to reduce the inflammation post operation in rabbit eyes [13]. Duncan et al. chose a strongly hydrophobic poly-methylmethacrylate (PMMA)-based IOL for coating a hydrophobic drug, thapsigargin, an inhibitor of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase, by immersion. In a human lens capsular bag culture, thapsigargin was released, slowly reaching LECs and leading to inhibition of the growth in residual anterior LECs at drug concentrations as low as 200 nM [14]. However, the process of coating the IOL, such as the drying procedures, raised the concern of causing toxic anterior segment syndrome and blocking the visual axis [13].

Table 1.

Conventional pharmacological approaches to PCO prophylaxis.

| Reference | Drug Used | Treatment Dose and Length | Application Methods in the Capsular Bag (In Vivo Models) |

Drug Action | Therapeutic Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | Distilled water | 0.1 mL for 3 min | Dropping water with a modified syringe using fluid/air exchange technique (Human) |

Hypoosmotic stress |

][22]. Compared to conventional coating systems, ultrasonic spray nozzles produced atomized PLGA drop sizes which allowed for a more precise and more controllable coating on the haptics of the IOL without damaging the optical part. The drug-loaded IOL containing either bromfenac or indomethacin displayed excellent anti-inflammatory and anti-PCO effects. Interestingly, despite using the same drug-loaded IOL, the drug release profiles of bromfenac and indomethacin were distinct. The release duration was 56 days for indomethacin versus 14 days for bromfenac, probably due to drug–PLGA interactions.

Spin-coating is another simple, reliable polymer coating technique for the preparation of thin films on substrates for drug deposition. Lu et al. developed the CsA@PLGA-IOL with a concentric annular coating for anti-inflammation post cataract surgery. The drug loading density and encapsulation efficiency of the drug cyclosporin A (CsA) were optimized by adjusting process parameters such as rotation speed, time duration and polymer concentrations. In LECs, CsA induced autophagic cell death, the key self-degradative cellular process. Intraocular implantation of a CsA@PLGA-IOL in rabbits prevented PCO formation without opacity on the central region; however, the optical resolution was influenced by the thicker peripheral ring coating areas in this particular ring-patterned coating of the IOL [23]. Supercritical impregnation is a new technology that does not require that organic solvents be used in the pre-soaking and spray-coating methods. In a recent study, to coat the IOL polymer with a lipophilic antimetabolite drug, methotrexate, the protected IOL was placed within a high-pressure cell and exposed to the drug dissolved in supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO2) [24]. scCO2 is recognized as a safe impregnation carrier. By varying the conditions, such as pressure and duration, different encapsulated amounts of methotrexate within the hydrophobic polymeric IOL support were achieved (i.e., 0.43–0.75 µg•mg−1 IOL). Finally, the drug can also be directly grafted onto the activated IOL via chemical reaction. For example, the PEI-coated IOL was immersed into a poly (PEGMA-co-GMA) (PPG) solution followed by immobilization of DOX on the surface of the PPG grafted substrate of IOL though the reaction of epoxy and amino groups. The multifunctional IOL surface modification exhibited sustained DOX release, inhibited adhesion and proliferation of LECs and reduced significantly the incidence of PCO in rabbit eyes [25].

2.2. Development of Non-IOL Dosage Forms

Other nanotechnology-enabled dosage forms have been developed to adapt various administration routes, such as injectable formulations or implantable pellet/inserts [28][29][30][31]. A composite docetaxel (DTX) capsular tension ring (CTR) was fabricated via the polymerization of high internal phase emulsion (poly HIPES) of porous PMMA. The DTX-CTR not only enhanced the bending strength of materials made into the CTR for the capsular bag support, but it also effectively suppressed the occurrence of PCO for up to 6 weeks without damage to normal ocular tissues [28]. A PLGA-based, DEX-loaded implant pellet was manufactured using a bench-top pellet press. This implant system has a diameter of 2 mm and a thickness of about 1.5 mm and can be injected readily through standard small incision during cataract surgery. It achieved a long-acting anti-inflammation effect by releasing the drug for up to 42 days with near zero-order kinetics without signs of toxicity in vivo [30]. Hydrogel-based hybrid NP depots require intraocular administration via periocular or intracameral injections. For example, genistein (Gen)-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier synthesized by homogenization emulsification was subsequently mixed into a solution of two drugs, DEX and moxifloxacin (MOX), to prepare a temperature-sensitive in situ hydrogel (GenNLC-DEX-MOX hydrogel). GenNLC-DEX-MOX hydrogel exhibited differential drug release kinetics, leading to reduced inflammation, proliferation and myofibroblast transformation of the LECs in the process of PCO [29].

Table 2.

Nanotechnology enabled drug delivery for PCO prophylaxis.

| Drug-Loaded IOL | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Fabrication Method (Loaded Drug) |

Part of IOL Modification | IOL Material | Drug Loading | Release Profile | Release Medium | Release Duration (t | 50 | /t | 90 | in Days) | Maximum Release% | ||||||

| Damaged LECs from the anterior capsule without damage to intraocular structures. | ||||||||||||||||||

| [16] | IOL immersion into the BP-DOX solution via facial activation-immersion | (Doxorubicin) | Non-optical | Hydrophobic acrylic | / | Photo-responsive | PBS (pH 7.4) |

16 days (104/1148) |

13% | |||||||||

| [3] | Sorbinil | Oral: 200 mg or 400 mg q.d for 7 days; Topical: 0.5 mg up to 14 h |

Oral and topical (Human) |

Aldose reductase inhibitor (anti-oxidation) |

Length of treatment was too short to effect lens sugar or sugar alcohol levels. | |||||||||||||

| [17] | Rapa@Ti | 3 | C | 2 | was deposited onto the oxygen plasma-activated IOL with a spin-coater (Rapamycin) |

Optical | Hydrophobic acrylic | / | NIR-triggered | Aqueous humor | 2 days (0.43/2.9) |

74% | [4] | 10 mg/kg | Intraperitoneal injection (Mice) | Inhibition of LEC EMT in mice. | ||

| [18] | DOX@Exos immobilized on the aminated IOL surface by electrostatic self-assembling (Doxorubicin) |

Optical | [5] | Dexamethasone | Single dose: 4 mg/mL | Subconjunctival injection (Rabbit) |

Anti-inflammation | Reduced LEC proliferation on the posterior capsule and effectively prevented PCO | ||||||||||

| Diclofenac | Single dose: 2.5 mg/mL | Injection with an anterior chamber cannula (Rabbit) |

||||||||||||||||

| RGD peptide | a | Single dose: 2.5 mg/mL | Anti-adhesion | |||||||||||||||

| Hydrophobic acrylic | / | A slow and continuous release | PBS | (pH 7.4) | 3 days | (6.3/264) |

40% | |||||||||||

| [19] | Fluorine ion beam-activating IOL was soaked in 5-Fu-CSNP suspension (5-Fluorouracil) |

Optical | Hydrophobic PMMA | / | A burst release of the drug in 2 h followed by slow release | PBS (pH 7.2) |

4 days (0.085/2.8) |

100% | ||||||||||

| [20] | The activated IOL alternatively coated with heparin and drug-loaded NPs (CTDNPs by layer-by-layer assembly (Doxorubicin) |

Optical | Hydrophobic acrylic | / | pH-responsive; no burst release | Acetate | EDTA | a | Single dose: 8 mg/mL | |||||||||

| buffer | Mitomycin C | Single dose: 0.04 mg/mL | Antimetabolites | |||||||||||||||

| (pH 5.5) | 7 days | (4.4 × 10 | 4 | /9.6 × 10 | 7 | ) | 7.2% | |||||||||||

| [21][22] | Drug-loaded PLGA was sprayed by ultrasonic coating system (Bromfenac or Indomethacin) |

Plate haptics | Hydrophobic acrylic | 0.1 mg | Biphasic release profiles | PBS | Bromfenac: 14 days (0.93/5.9) Indomethacin: 56 days (12/89) |

Bromfenac: 91% Indomethacin: 80% |

||||||||||

| [23] | Drug-loaded PLGA coating by spin-coating (Cyclosporin A) |

Thin center and thick periphery | Hydrophobic acrylic | / | Four-phase release: (1) exponential; (2) linear; (3) burst; (4) plateaued. | PBS (pH 7.4) |

120 days (23/126) |

78% | ||||||||||

| [24] | Supercritical impregnation (Methotrexate) |

Optical | Hydrophobic acrylic | 0.0069 mg | Sustained release | Aqueous humor (pH 7.2) |

87 days (31/143) |

>90% | [6] | |||||||||

| [ | N-Acetylcysteine | Single dose: 25 μL, 10 mmol/L | Injection into the eye chamber (Mouse) |

Antioxidant | Attenuated LEC EMT signaling. | |||||||||||||

| 25] | The aminated IOL chemically grafted with PPG followed by DOX immobilization via the reaction of epoxy and amino groups (Doxorubicin) |

Optical | Hydrophobic acrylic | / | pH-responsive | Sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) | 7 days (4.8 × 10 | 4 | /1.6 × 10 | 8 | ) | 8.1% (pH 5.5) |

[7] | EDTA | 1, 2.5, and 5 mg with a single dose | Intracameral injection (Rabbit) | MMP inhibitor | Reduced the degree of PCO by suppressing the matrix metalloproteinase activity. |

| [26] | Drug-loaded polydopamine coating followed by MPC immobilization via immersion (Doxorubicin) |

Optical | Hydrophobic acrylic | / | A burst release of 75% of drug in the first 24 h followed by drug sustained release | Sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) |

21 days (0.098/9.6) |

>85% (PDA(DOX)-MPC) |

[8] | Distilled water | / | Injection through SCI device (Rabbit) | Hypoosmotic stress | Reduced PCO development without toxicity to surrounding ocular tissues. | ||||

| [27] | Mitomycin C | 0.4 mg/mL for 2 min | Antimetabolite | |||||||||||||||

| Soaking IOLs in solution containing dual drugs (Moxifloxacin/ketorolac) | Optical | Hydrophobic G-free | ® | and hydrophilic CI26Y | / | An extended release of dual drugs for 26 days | PBS | 26 days | CI26Y IOL: MOX: 52 μg ketorolac: 63 μg G-free | ® | IOL: MOX: 6 μg ketorolac: 7 μg |

|||||||

| Other DSS | [9] | Actinomycin D | a | 10 μg/mL for 5 min | Flush with the Perfect Capsule Device and sodium hyaluronate (Rabbit) |

Anti-proliferation | Reduced the formation of visible capsular opacification. | |||||||||||

| Reference | Drug Carrier | Fabrication Method | Drug Loading | Release Kinetics | Release Medium | Release Duration | (t50 /t90 in Days) | Maximum Release% | Cycloheximide | a | 25 μg/mL for 5 min | |||||||

| [28] | Capsular tension ring (DTX-CTR) |

Porous PMMA via polyHIPE in combination with P(HEMA-co-MMA)-PMMA composite (Docetaxel) |

/ | Porous structure controlled sustained release | PBS (pH 7.4) |

6 weeks | 5.3 mg/g | [10] | Methotrexate | a | 10 μM for 5 min | |||||||

| [29] | Nanoparticle–hydrogel composite (GenNLC-DEX-MOX hydrogel) | Human capsular rhexis specimens; Lens refilling | NPs were mixed with the gel solution (Combination of Genistein | (Rabbit) |

Antimetabolite | Moxifloxacin and Dexamethasone) | Gen: 10 mg | Ablated viable LECs ex vivo, and delayed PCO formation in vivo. | ||||||||||

| DEX: 4 mg/mL | Actinomycin D | a | 10 μM for 5 min | Anti-proliferation | ||||||||||||||

| MOX: 2 mg/mL | Multiple drug release with differential kinetics | PBS | (pH 7.0–7.6) | Gen: 40 days | (20/127) DEX: 40 days (6.4/24) MOX: 10 days (1.8/7.4) |

63% (Gen) 97% (DEX) 99% (MOX) |

||||||||||||

| [30] | PLGA microparticles (DXM-PLGA) |

Oil-in-water ( | o | / | w | ) emulsion-solvent extraction method followed by bench-top pellet press (Dexamethasone) |

0.32 mg | Initial burst release followed by a sustained release | BSS (pH 7.4) |

22 days (18/45) |

53% | [11] | Sodium Hyaluronate | |||||

| [31] | 2.3% for 5 min | NPs (MePEG-PCL DOX NPs) |

Solvent evaporation | Lens refilling (Monkey) |

Influencing LEC growing pattern | No capsular bag fibrosis. | ||||||||||||

| [12] | Sodium Hyaluronate | 1.4% for 3 min | Refilling (Rabbit) |

Anti-proliferation | Distilled water and EDTA were most effective against PCO development. | |||||||||||||

| Balanced salt solution | / | |||||||||||||||||

| Mitomycin C | 0.2 mg/mL for 3 min | |||||||||||||||||

| EDTA | 10 and 15 mM for 3 min | |||||||||||||||||

| 5-Fluorouacil | 33 mg/mL for 3 min | |||||||||||||||||

| Acetic acid | 3%, 0.3% and 0.003% for 3 min | |||||||||||||||||

| [13] | Dexamethasone | IOL incubated in 1 mg/mL | Implantation of IOL pre-soaked with the drug (Rabbit) |

Anti-inflammation | Reduced postoperative inflammation. | |||||||||||||

| [14] | Thapsigargin | IOL incubated in 0.2–2 μM | Insert into the capsular bag (Human) |

Inhibitor of endoplasmic reticulum (Ca | 2+ | )-ATPase | Reduced LEC growth in the capsular bag. | |||||||||||

a The drugs were combined. Abbreviations: EDTA—ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; EMT—epithelial–mesenchymal transition; MMP—matrix metalloproteinase; SCI—sealed capsular irrigation; RGD peptide—Arg-Gly-Asp tripeptide recognition sequence.

2. Nanotechnology-Based Drug Delivery

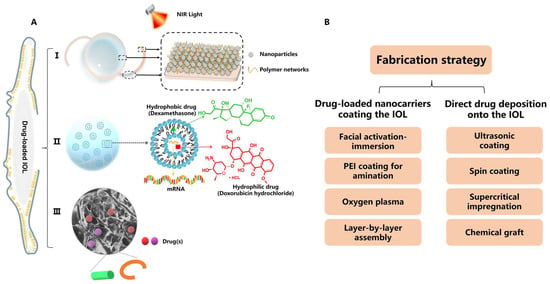

Various pre-clinical prophylactic DDSs have been developed over the past decade for PCO treatment, including I. drug-loaded IOLs, II. nanocarrier and hydrogel composites and III. implants (e.g., capsular tension ring, and solid pellet/inserts) (Figure 12A). Those DDSs can be designed for stimuli-responsive controlled drug release, such as external near-infrared (NIR) light, and for loading versatile drugs (e.g., anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, chemotherapeutic drugs and mRNA for gene therapy). The data presented in Table 2 [16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31] were selected from the literature based on the following criteria: (1) pharmacological agents(s) were loaded within the DDS for PCO prevention and (2) data describing the measurement of drug release were available. Table 2 details the fabrication methods, drug loading and drug release of anti-PCO DDSs, in which IOLs modified for a drug reservoir have been extensively studied for post-cataract operative care. Based on the fabrication processes, anti-PCO DDS are classified into the following types: (1) drug-loaded nanocarriers coating the IOL; (2) direct drug deposition onto the IOL; (3) other dosage forms, including nanoparticles (NPs), implants and hydrogel composites. To control the pathological activities of LECs, all of these DDSs are capable of sustaining drug release for an extended period of time, while causing no toxicity to normal ocular tissues.

Figure 12. (A) Illustration of DDSs employing nanotechnology for PCO prevention, including I. drug-loaded IOL, II. NPs and their hydrogel composite and III. implants such as capsular tension ring and solid pellet/inserts. Inset: an example of polymeric nanostructure carrying pharmacological agent(s). (B) Fabrication strategies of drug-loaded IOLs for PCO therapy.

2.1. Surface Modification of IOL Materials

An IOL-enabled DDS is an integrated object that is implanted along with the phacoemulsification. The design of a drug-loaded IOL involves coating the optical surface, rim, or haptics of the IOL with the drug-loaded nanocarriers and free drug. The specific fabrication strategies are outlined in Figure 2B. Most IOLs coated with drug-loaded nanocarriers are prepared with a single layer, using one of several different methods [16][17][18][19]. Mao et al. fabricated BP-DOX@IOL by integration of doxorubicin (DOX)-loaded black phosphorus nanosheets onto the non-optical section of the IOL via facial activation-immersion. BP-DOX@IOL exhibited a superior ability to inhibit PCO in vivo [16]. In another study, the IOL was surface-activated by oxygen plasma and further deposited with rapamycin (Rapa)-loaded Ti3C2 nanosheets (Rapa@Ti3C2) using spin-coating. Rapa@Ti3C2-IOL inhibited PCO for four weeks without obvious pathological damage in healthy ocular structures [17]. Nanomaterials applied in the above two examples (BP-DOX@IOL and Rapa@Ti3C2-IOL) were intrinsically photo-responsive, and their drug release was triggered by irradiation with near-infrared (NIR) light [16][17]. The IOL can also be activated by soaking the IOL overnight in an aqueous solution of polyethyleneimine (PEI) to generate a positively charged substrate surface before coating with NPs. For example, DOX@Exos-IOL was prepared via the immersion of a PEI-coated IOL in a DOX-loaded exosomes suspension. Exosomes as nanoscale extracellular vesicles have been used as a DDS due to their high biocompatibility, low toxicity and homologous targeting. In rabbits with phacoemulsification combined with IOL implantation, DOX@Exos-IOL was biocompatible and significantly eliminated LECs between the optical IOL and the anterior and posterior capsule [18]. Unlike the single-layer-coated IOL, Lin’s group developed a polysaccharide multilayer modified IOL [20]. In this case, the PEI-coated IOL was sequentially immersed in heparin solution and then chitosan NPs, followed by rinsing and drying to obtain an HEP/CTDNP-modified IOL via layer-by-layer deposition. At pH 5.5, which resembles the slightly acidic cellular microenvironment of the LECs, IOLs modified with HEP/CTDNP exhibited slow release of DOX and no burst release [20].

Pharmacological agents can be deposited directly onto the IOL via physical coating or chemical grafting [21][22][23][24][25][26]. For the drugs bromfenac and indomethacin, Yao’s group used ultrasonic spray technology to deposit a poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) coating containing the drug onto the plate haptics of an IOL [21

| (Doxorubicin) | |

| 0.25 mg | |

| Initial burst release followed by a sustained release of the drug | |

| PBS | |

| (pH 7.4) | |

| 10 days | |

| (4.1/99) | |

| 75% | |

All DDSs were administered via implantation unless otherwise specified; reference [31] used subconjunctival injections. All the data reported for the maximum drug release were obtained from the papers’ release curves unless otherwise specified; the data point obtained by Getdata Software, and t50 and t90 were determined using DDsolver Software (see Supplementary Material Table S4). In references [24][25][26], the maximum drug release was calculated using the reported values of released drug amount divided by total drug loading amount. Abbreviations: BP-DOX—doxorubicin-loaded black phosphorus nanosheets; CI26Y—a hydrophilic IOL material, chemically crosslinked copolymer; CSNP—5-Fluorouracil-loaded chitosan nanoparticles; CTDNP—doxorubicin-incorporated chitosan nanoparticles were fabricated by sodium tripolyphosphate gelation; DOX@Exos—doxorubicin-loaded exosomes; DTX-CTR—docetaxel-loaded capsular tension ring; DXM-PLGA—dexamethasone-loaded PLGA microspheres; 5-Fu- PLGA—poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid); GenNLC-DEX-MOX hydrogel—temperature-sensitive drug delivery system carrying dexamethasone, moxifloxacin and genistein, nanostructured lipid carrier modified by mPEG-PLA based on F127/F68 as hydrogel; G-free@—a hydrophobic acrylic-based IOL material; MePEG-PCL DOX NPs—poly (ethylene glycol) methyl ether-block-poly (ε-caprolactone) doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles; MPC—2-methacryloxyethyl phosphorylcholine; Rapa@Ti3C2—ultrathin Ti3C2 MXene nanosheet-coated IOL loaded with Rapamycin; PMMA—poly (methyl methacrylate); P(HEMA-co-MMA)-PMMA—copolymer of methyl methacrylate and 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate combined with the polyHIPE to form a novel composite.

3. Pros and Cons of Conventional and Nanotechnology-Based Drug Delivery

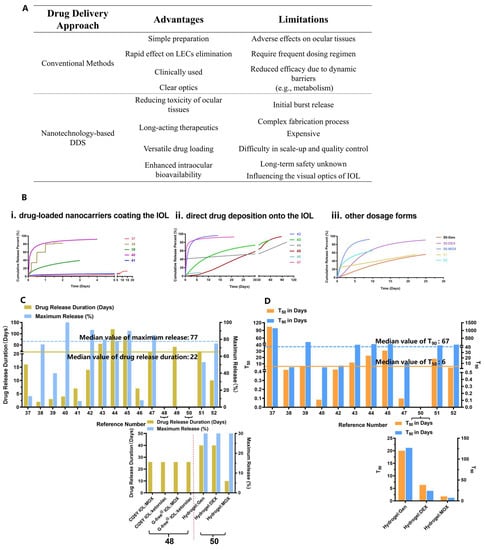

Both conventional and nanotechnology-based drug delivery can eliminate residual LECs to some extent, but each delivery method has its own advantages and limitations (Figure 23A). The conventional drug delivery shown in Table 1 is often assisted by mini devices (e.g., SCI) to isolate the capsular bag for direct administration of a high dose (i.e., milligrams) of chemotherapeutic drugs. Despite its inhibition of PCO formation in animal models and reported potency in clinical applications, the use of conventional delivery of free drugs in the clinic is limited, due to the adverse effects on surrounding healthy ocular structures. In addition, a drug administered intraocularly may be eliminated quickly owing to (1) the rapid turnover of aqueous humor (90–100 min) via the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal and (2) transport through the blood–aqueous barrier into blood circulation [32][33]. Thus, direct administration does not provide a long-acting control of PCO development.

Figure 23. Analysis of prophylactic drug delivery strategies for PCO. (A) Advantages and limitations of conventional and nanotechnology-based drug delivery; (B) Fitted drug release profiles of anti-PCO DDSs shown in Table 2, including (i) drug-loaded NPs coating the IOL; (ii) direct drug deposition onto the IOL and (iii) non-IOL DDSs, including NPs, hydrogel and implants. The number shown on the X-axis corresponds to reference numbers in Table 2, and left- and right- y axis are drug release duration and maximum release percent, respectively; (C) Drug release duration and maximum drug release percent of nanotechnology-based DDS; (D) The time t50 and t90 when the fraction of drug release reached 50% and 90%, respectively, for nanotechnology-based DDSs. Note, (i) the data on “drug release duration” for references [27][28] were shown in Figure 23C, and not displayed in Figure 23B,D due to lack of data on drug release; (ii) the data on t50 and t90 for references [20][25] were too large to display in the graph in Figure 23D, and references [27][28] did not provide sufficient data for calculating t50 and t90. (iii) X-axes of the two graphs in Figure 23C,D represent the data on drug combination.

The value of novel nanotechnology-assisted pharmacological interventions in concert with optimal IOLs is increasingly recognized by clinicians [34]. As shown in Table 2, currently, most dosage forms are drug-loaded IOLs, which are implanted into the capsular bag during cataract surgery. ThWe researchers used the DDsolver program for modeling and comparison of drug release profiles of (i) drug-loaded NPs coating the IOL, (ii) direct drug deposition onto the IOL and (iii) other dosage forms (i.e., NPs, hydrogel, implants) (Figure 23B) [35]. It was found that anti-PCO DDSs studied in Table 2 exhibited various drug release profiles, and the prolonged drug release duration and maximum drug release percent were found to be 22 days and 77%, respectively (Figure 23C). Further analysis of the fitted drug release profiles revealed that the median values for 50% (t50) and 90% (t90) drug release were about 6 days and 67 days, respectively (Figure 23D). Sustained drug release over a protracted period can improve drug potency against LECs. For example, IOLs modified with 5-Fu chitosan nanoparticles (Nano-5-Fu-IOL) exhibited the half inhibition dose of 0.2 μg/mL against human LECs compared to 1 μg/mL for the free drug solution [19]. In vivo, direct implantation of Nano-5-Fu-IOL at a dose of 5-Fu equal to 19.5 mg (0.2 mL, 97.8 mg/mL) markedly inhibited the occurrence of PCO without inflammation in rabbit eyes. On the other hand, direct injection of a high dose of a 5-Fu solution (33 mg/mL) was ineffective in preventing anterior capsule proliferation [12][19]. These data indicate that the DDS can lower the therapeutic dose by a hundred- or thousand-fold which, in turn, leads to reduced adverse effects.

References

- Zhang, R.P.; Xie, Z.G. Research Progress of Drug Prophylaxis for Lens Capsule Opacification after Cataract Surgery. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 2020, 2181685.

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, L.; Jin, H.; Li, J.; Zhao, P. Air/Fluid-Dropping Technique for Intracapsular Distilled Water Application: A Vitrectomy Approach for Selective Targeting of Lens Epithelial Cells. Retina 2019, 39, 364–370.

- Crabbe, M.J.; Petchey, M.; Burgess, S.E.; Cheng, H. The penetration of Sorbinil, an aldose reductase inhibitor, into lens, aqueous humour and erythrocytes of patients undergoing cataract extraction. Exp. Eye Res. 1985, 40, 95–99.

- Zukin, L.M.; Pedler, M.G.; Groman-Lupa, S.; Pantcheva, M.; Ammar, D.A.; Petrash, J.M. Aldose Reductase Inhibition Prevents Development of Posterior Capsular Opacification in an In Vivo Model of Cataract Surgery. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 3591–3598.

- Inan, U.U.; Oztürk, F.; Kaynak, S.; Kurt, E.; Emiroğlu, L.; Ozer, E.; Ilker, S.S.; Güler, C. Prevention of posterior capsule opacification by intraoperative single-dose pharmacologic agents. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2001, 27, 1079–1087.

- Wei, Z.B.; Caty, J.; Whitson, J.; Zhang, A.D.; Srinivasagan, R.; Kavanagh, T.J.; Yan, H.; Fan, X.J. Reduced Glutathione Level Promotes Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Lens Epithelial Cells via a Wnt/Chi-Catenin-Mediated Pathway Relevance for Cataract Therapy. Am. J. Pathol. 2017, 187, 2399–2412.

- Hazra, S.; Guha, R.; Jongkey, G.; Palui, H.; Mishra, A.; Vemuganti, G.K.; Basak, S.K.; Mandal, T.K.; Konar, A. Modulation of matrix metalloproteinase activity by EDTA prevents posterior capsular opacification. Mol. Vis. 2012, 18, 1701–1711.

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, J.S.; Joo, C.K. Comparison of posterior capsule opacification in rabbits receiving either mitomycin-C or distilled water for sealed-capsule irrigation during cataract surgery. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2007, 35, 755–758.

- Koopmans, S.A.; Terwee, T.; van Kooten, T.G. Prevention of capsular opacification after accommodative lens refilling surgery in rabbits. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 5743–5755.

- Sternberg, K.; Terwee, T.; Stachs, O.; Guthoff, R.; Löbler, M.; Schmitz, K.P. Drug-induced secondary cataract prevention: Experimental ex vivo and in vivo results with disulfiram, methotrexate and actinomycin D. Ophthalmic Res. 2010, 44, 225–236.

- Koopmans, S.A.; Terwee, T.; Hanssen, A.; Martin, H.; Langner, S.; Stachs, O.; van Kooten, T.G. Prevention of capsule opacification after accommodating lens refilling: Pilot study of strategies evaluated in a monkey model. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2014, 40, 1521–1535.

- Fernandez, V.; Fragoso, M.A.; Billotte, C.; Lamar, P.; Orozco, M.A.; Dubovy, S.; Willcox, M.; Parel, J.M. Efficacy of various drugs in the prevention of posterior capsule opacification: Experimental study of rabbit eyes. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2004, 30, 2598–2605.

- Kugelberg, M.; Shafiei, K.; Van Der Ploeg, I.; Zetterström, C. Intraocular lens as a drug delivery system for dexamethasone. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010, 88, 241–244.

- Duncan, G.; Wormstone, I.M.; Liu, C.S.; Marcantonio, J.M.; Davies, P.D. Thapsigargin-coated intraocular lenses inhibit human lens cell growth. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 1026–1028.

- Maloof, A.; Neilson, G.; Milverton, E.J.; Pandey, S.K. Selective and specific targeting of lens epithelial cells during cataract surgery using sealed- capsule irrigation. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2003, 29, 1566–1568.

- Mao, Y.Y.; Li, M.; Wang, J.D.; Wang, K.J.; Zhang, J.S.; Chen, S.Y.; Liu, X.; Liang, Q.F.; Gao, F.; Wan, X.H. NIR-triggered drug delivery system for chemo-photothermal therapy of posterior capsule opacification. J. Control. Release 2021, 339, 391–402.

- Ye, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, T.; Gao, L.; Hu, H.; He, Q.; Jin, H.; Li, Z. Two-dimensional ultrathin Ti(3)C(2) MXene nanosheets coated intraocular lens for synergistic photothermal and NIR-controllable rapamycin releasing therapy against posterior capsule opacification. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 989099.

- Zhu, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, D.; Wen, S.; Shen, L.; Lin, Q. Augmented cellular uptake and homologous targeting of exosome-based drug loaded IOL for posterior capsular opacification prevention and biosafety improvement. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 15, 469–481.

- Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, J.P.; Ma, X.Y.; Li, Y.; Cheng, J.W.; Wei, R.L. Sustained Release of 5-Fluorouracil from Chitosan Nanoparticles Surface Modified Intra Ocular Lens to Prevent Posterior Capsule Opacification: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 29, 208–215.

- Han, Y.M.; Tang, J.M.; Xia, J.Y.; Wang, R.; Qin, C.; Liu, S.H.; Zhao, X.; Chen, H.; Lin, Q.K. Anti-Adhesive And Antiproliferative Synergistic Surface Modification Of Intraocular Lens For Reduced Posterior Capsular Opacification. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 9047–9061.

- Zhang, X.; Lai, K.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Ni, S.; Lu, B.; Grzybowski, A.; Ji, J.; et al. Drug-eluting intraocular lens with sustained bromfenac release for conquering posterior capsular opacification. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 9, 343–357.

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, C.; Ni, S.; Han, H.; Shentu, X.; Ye, J.; et al. Prophylaxis of posterior capsule opacification through autophagy activation with indomethacin-eluting intraocular lens. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 23, 539–550.

- Lu, D.; Han, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, S.; Qie, J.; Qu, J.; Lin, Q. Centrifugally concentric ring-patterned drug-loaded polymeric coating as an intraocular lens surface modification for efficient prevention of posterior capsular opacification. Acta Biomater. 2022, 138, 327–341.

- Ongkasin, K.; Masmoudi, Y.; Wertheimer, C.M.; Hillenmayer, A.; Eibl-Lindner, K.H.; Badens, E. Supercritical fluid technology for the development of innovative ophthalmic medical devices: Drug loaded intraocular lenses to mitigate posterior capsule opacification. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 149, 248–256.

- Xia, J.; Lu, D.; Han, Y.; Wang, J.; Hong, Y.; Zhao, P.; Fang, Q.; Lin, Q. Facile multifunctional IOL surface modification via poly(PEGMA-co-GMA) grafting for posterior capsular opacification inhibition. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 9840–9848.

- Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Tang, J.; Han, Y.; Lin, Q. Drug-Eluting Hydrophilic Coating Modification of Intraocular Lens via Facile Dopamine Self-Polymerization for Posterior Capsular Opacification Prevention. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 1065–1073.

- Topete, A.; Tang, J.; Ding, X.; Filipe, H.P.; Saraiva, J.A.; Serro, A.P.; Lin, Q.; Saramago, B. Dual drug delivery from hydrophobic and hydrophilic intraocular lenses: In-vitro and in-vivo studies. J. Control. Release 2020, 326, 245–255.

- Lei, M.; Peng, Z.; Dong, Q.; He, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yan, M.; Zhao, C. A novel capsular tension ring as local sustained-release carrier for preventing posterior capsule opacification. Biomaterials 2016, 89, 148–156.

- Yan, T.Y.; Ma, Z.X.; Liu, J.J.; Yin, N.; Lei, S.Z.; Zhang, X.X.; Li, X.D.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, J. Thermoresponsive GenisteinNLC-dexamethasone-moxifloxacin multi drug delivery system in lens capsule bag to prevent complications after cataract surgery. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13.

- Chennamaneni, S.R.; Mamalis, C.; Archer, B.; Oakey, Z.; Ambati, B.K. Development of a novel bioerodible dexamethasone implant for uveitis and postoperative cataract inflammation. J. Control. Release 2013, 167, 53–59.

- Guha, R.; Chowdhury, S.; Palui, H.; Mishra, A.; Basak, S.; Mandal, T.K.; Hazra, S.; Konar, A. Doxorubicin-loaded MePEG-PCL nanoparticles for prevention of posterior capsular opacification. Nanomedicine 2013, 8, 1415–1428.

- Urtti, A. Challenges and obstacles of ocular pharmacokinetics and drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006, 58, 1131–1135.

- Freddo, T.F. Shifting the paradigm of the blood-aqueous barrier. Exp. Eye Res. 2001, 73, 581–592.

- Shihan, M.H.; Novo, S.G.; Duncan, M.K. Cataract surgeon viewpoints on the need for novel preventative anti-inflammatory and anti-posterior capsular opacification therapies. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2019, 35, 1971–1981.

- Zhang, Y.; Huo, M.; Zhou, J.; Zou, A.; Li, W.; Yao, C.; Xie, S. DDSolver: An add-in program for modeling and comparison of drug dissolution profiles. AAPS J. 2010, 12, 263–271.

More