Hydrogen is an industrial gas that has showcased its importance in several well-known processes such as ammonia, methanol and steel productions, as well as in petrochemical industries. Besides, there is a growing interest in hydrogen production and purification owing to the global efforts to minimize the emission of greenhouse gases. Nevertheless, hydrogen which is produced synthetically is expected to contain other impurities and unreacted substituents (e.g., carbon dioxide, nitrogen and methane), such that subsequent purification steps are typically required for practical applications. In this context, membrane-based separation has attracted a vast amount of interest due to its desirable advantages over conventional separation processes, such as the ease of operation, low energy consumption and small plant footprint. Efforts have also been made for the development of high-performance membranes that can overcome the limitations of conventional polymer membranes. In particular, the studies on graphene-based membranes have been actively conducted most recently, showcasing outstanding hydrogen-separation performances.

- graphene

- membrane

- H2 separation

- permeability

- selectivity

- upper bound

1. Introduction

Hydrogen (H2) is an important industrial gas that is heavily utilized in the petrochemical industries. For instance, H2 is involved in the hydrodesulfurization process, which removes sulfur from natural gas [1][2][1,2] for subsequent petroleum refining process. In addition, H2 is also employed as the main reactant in productions of ammonia, methanol and steel [3][4][5][3–5]. More importantly, in recent years, H2 has attracted a large amount of attentions as a carbon-free energy resource possessing the highest energy density per unit mass (120–142 MJ/kg). This is because the use of H2 produces water as the only byproduct [6], in contrast to conventional fossil fuels that inevitably emit carbon dioxide (CO2), a greenhouse gas [7][8][7,8]. This behavior has led to a rapid increase in demand of hydrogen, such that the reported global demand is registered at 73.9 megatons (Mt) in 2018 [9].

In general, H2 is produced by using the natural gas (mainly methane (CH4)) via a steam-reforming process, with the aid of high-temperature steam. It should be noted that this process accounts for the major portion in global H2 production in comparison to other alternative approaches, such as partial methane oxidation and water splitting [10]. However, this process inevitably generates undesirable impurities, such as CO2, CH4 and nitrogen (N2). Notably, it was reported that the steam-reforming accounts for approximately 830 million tons of CO2 emission annually [9]. On the other hand, environmentally-benign process such as water splitting via electrolysis or photolysis is able to satisfy a mere 3.9% of the global demand, such that, at current stage, it is difficult to phase out the conventional process for H2 production [11][12][11,12]. In this regard, it is necessary to separate H2 from other components, particularly CO2 and CH4, which are classified as greenhouse gases under the Kyoto Protocol [13][14][15][16][13–16].

The separation of H2 from gas mixtures can be conducted using pressure-swing adsorption (PSA) and cryogenic distillation, allowing the production of high-purity H2 [17][18][19][20][21][17–21]. However, both processes generally require extensive compression work and large energy penalties, leading to a high production cost [22][23][24][22–24]. Therefore, membrane-based separation has been considered as an alternative unit operation due to its simple operation, small plant footprint and high energy efficiency [25][26][27][25–27]. In general, polymeric membranes are commonly utilized in gas separations due to an excellent processability. This allows the fabrication of membranes into various forms, including spiral wound or hollow fiber, a well-established and scalable synthesis process together with a desirable mechanical stability. However, the performance of the polymeric membrane is limited by the trade-off relationship between permeability and selectivity, as evidenced by the Robeson plot [28][29][28,29]. It is considerably challenging to optimize both permeability and selectivity in polymeric membranes, as the gas transport properties are governed by the solution-diffusion mechanism [30][31][32][30–32]. Efforts in improving the gas separation performance have been made by employing molecular sieves such as zeolites, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and microporous organic polymers (MOPs) as membrane materials. However, these membranes suffer from limited scalability and poor mechanical stability [33][34][33,34].

In recent years, various two-dimensional (2D) materials such as MXene [35][36]

-TMD) [37], layered double hydroxides (NiAl-CO3-LDH) [38], MOF-based nanosheets [39], covalent organic framework (COF)-based nanosheets [40], graphene [41] and carbon nitrides [42] have been developed and studied for potential applications in many fields. Their uniquely high aspect ratios (atomically thin) allow such materials to be assembled into ultrathin membranes exhibiting a high permeation flux [43]. Among the 2D materials, graphene-based membranes have attracted a vast amount of interest due to their high thermal and mechanical stability, along with the residing functional groups, allowing a further tuning of the membrane structure. Thus, single-layer or graphene laminates were formed onto porous membrane supports to develop thin-film composite membranes [44][45][46], or graphene was employed as the filler material in mixed-matrix membrane (MMM) fabrications .[47][35,36], transition metal dichalcogenides (e.g., MoS2-TMD) [37], layered double hydroxides (NiAl-CO3-LDH) [38], MOF-based nanosheets [39], covalent organic framework (COF)-based nanosheets [40], graphene [41] and carbon nitrides [42] have been developed and studied for potential applications in many fields. Their uniquely high aspect ratios (atomically thin) allow such materials to be assembled into ultrathin membranes exhibiting a high permeation flux [43]. Among the 2D materials, graphene-based membranes have attracted a vast amount of interest due to their high thermal and mechanical stability, along with the residing functional groups, allowing a further tuning of the membrane structure. Thus, single-layer or graphene laminates were formed onto porous membrane supports to develop thin-film composite membranes [44–46], or graphene was employed as the filler material in mixed-matrix membrane (MMM) fabrications [47].

In this work, for the first time, the recent progress on graphene-based membranes for H2 separation was comprehensively reviewed, in contrast to previous reviews that broadly cover general gas separations using graphene membranes [48][49][50][48–50]. First, this review begins with the introduction of three commonly adopted membrane designs, namely single-layer graphene, multi-layer graphene laminates and graphene-based composite membranes or MMMs. This is followed by an overview on the recent progress in graphene-based membranes for H2 separation. The H2 separation performances are plotted together with the upper bound limits for H2/CO2, H2/N2 and H2/CH4 separations for effective benchmarking. The properties of the selected gases are summarized in Table 1 for reference. The studies on molecular simulation and modeling are also discussed in this review. Finally, the challenges, potential and future directions of graphene-based membranes for H2 separation are discussed in the conclusions section.

Table 1. Properties of the selected gases [51][52][51,52].

|

Gas |

Kinetic Diameter (Å) |

Polarizability × 1025 (cm3) |

Dipole Moment × 1018 (esu cm)(a) |

Quadrupole Moment × 1026 (esu cm2)(b) |

|

|

Helium |

He(c) |

2.55 |

2.05 |

0 |

0 |

|

Water vapor |

H2O(c) |

2.64 |

14.5 |

1.85 |

- |

|

Hydrogen |

H2 |

2.83 |

8.04 |

0 |

0.662 |

|

Carbon dioxide |

CO2 |

3.30 |

29.1 |

0 |

4.30 |

|

Nitrogen |

N2 |

3.64 |

17.4 |

0 |

1.52 |

|

Methane |

CH4 |

3.80 |

25.9 |

0 |

0 |

(a) Properties of polar molecules (presence of net force under uniform electric field). (b) Presence of net force under nonuniform electric field. (c) Helium (He) and water vapor (H2O) is included in the table as a reference.

2. Graphene-based Membrane

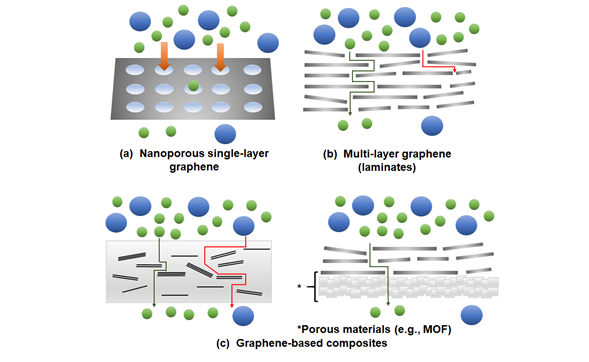

In this section, a brief overview on the various graphene membrane configurations, namely single-layer, multi-layer and graphene-based composites (Figure 1), is presented. We also invite readers to refer to the following references [53][54][55][53–55] in order to obtain a better insights on the development on graphene-based membranes under various configurations.

Figure 1. Possible membrane configurations that can be developed with the use of graphene: (a) Nanoporous single-layer graphene, (b) multi-layer graphene (laminates) and (c) graphene-based composites. MOF: metal-organic frameworks.

2.1. Single-layer Graphene

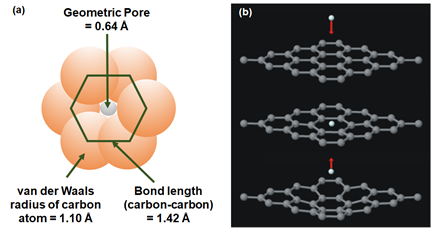

Graphene is a 2D nanomaterial in which carbon atoms are arranged in a hexagonal lattice via sp2 hybridization. Graphene possesses extraordinary thermal, electrical and mechanical properties due to the presence of long-range π-conjugation throughout the structure. Moreover, the chemical property of graphene can also be tuned so as to develop reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and graphene oxide (GO). In general, defect-free nonperforated single-layer graphene is not permeable to gas molecules. This is attributed to the delocalized π-electron clouds in the aromatic rings that blocks the penetration of any molecules [56][57][56,57]. As shown in Figure 2a, the geometric pore (0.64 Å) in the single-layer graphene that is calculated from the van der Waals radius of carbon (1.10 Å) is smaller than the kinetic diameter of helium (Table 1) [58][53,58]. Apart from this, the impermeability of gases in single-layer graphene was also verified with the aid of molecular dynamics (MD) simulation and density functional theory (DFT). The energy barrier that is required for monoatomic molecules (e.g., helium (He)) to pass through a nondefective graphene layer is calculated to be 18.8 eV based on the local density approximation (LDA). Given that the kinetic energy of the He atom is calculated to be 18.6 eV, it is not possible for He to permeate through the single-layer graphene sheet (Figure 2b) [59].

Figure 2. (a) Comparison among the van der Waals radius of a carbon atom (1.10 Å), carbon-carbon bond length (1.42 Å) and geometric pore (0.64 Å). It can be observed that the pores are too small to allow the penetration of gases. Reproduced with permission from Reference [58], copyright 2013 Elsevier. (b) Reflection of the He atom from the graphene surface upon transport through the available pores on nondefective single-layer graphene. Reprinted with permission from Reference [59], copyright 2008, AIP Publishing LLC.

2.2. Multi-layer Graphene

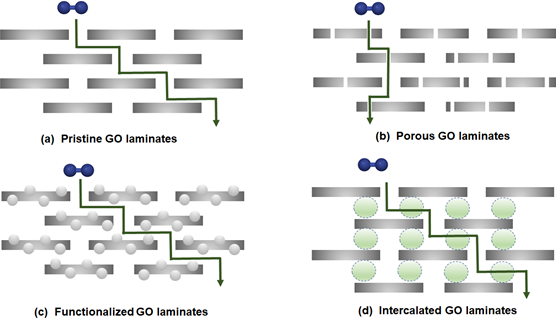

In comparison to a single-layer graphene membrane, the creation of multi-layer stacked graphene is considered to be technically viable, as multi-layer graphene laminates with high-quality and integrity can be readily developed less stringently in membrane design. To date, the utilization of multi-layer graphene for gas separation commonly involves the synthesis of GO, which is one of the main derivatives of graphene. This is attributed to its well-established synthesis method (graphite oxidation), as well as the presence of abundant functional groups on the basal and edge of graphene planes (e.g., epoxy, carboxyl and hydroxyl). As these hydrophilic functional groups allow GO to be dispersed stably in polar solvents such as water, GO can be processed into thin films and membranes. However, the development of a defect-free continuous film is necessary in order to prevent the undesirable nonselective transport of gases. This is typically accomplished by increasing the thickness of GO laminates. Nevertheless, such action leads to a compromise in gas permeability (or flux), as depicted by the Hagen-Poiseuille equation [60]. Besides, according to the calculations by Nielsen [61], if the graphene sheets are oriented perpendicular to the permeation direction, the diffusion length is expected to be 1450 times greater, with respect to the thickness of the graphene laminates (Figure 3a). Thus, various strategies such as porous graphene laminates (Figure 3b), functionalized GO laminates (Figure 3c) or intercalated GO laminates (Figure 3d) have been proposed to tune the resulting gas separation performance.

Figure 3. Possible configurations of graphene laminates: (a) pristine graphene oxide (GO) laminates, (b) porous GO laminates, (c) functionalized GO laminates and (d) intercalated GO laminates. Reproduced with permission from Reference [54], Creative Commons License CC BY 4.0.

2.3. Graphene-based Composites

Similar to other commonly reported porous materials (e.g., zeolites, MOFs and MOPs), graphene can serve as the filler in composite membranes or MMMs [62][63][64][47,62–64]. By utilizing the interlayer channels that are present in graphene laminates, the selective molecular transport of targeted gas can be realized. Apart from this, it has been reported that incorporation of graphene into the polymer matrix can improve the mechanical properties as compared to the pure polymeric membrane. For instance, the incorporation of 10 wt% GO into a Matrimid® 5218 membrane increased the Young’s modulus and tensile strength by 12% and 7%, respectively [47]. In a similar study, the incorporation of 5 wt% GO in an ODPA-TMPDA (4,4′-oxydiphthalic anhydride and 2,4,6-trimethyl-m-phenylenediamine) membrane was able to improve both the Young’s modulus (8%) and tensile strength (11%), respectively [65]. Such behavior has been attributed to a strong chemical interaction between GO rich in functional groups and the polymer matrix.

Moreover, GO has also been utilized as the building block in creating highly porous composite materials with 3D architectures. Typically, MOFs are selected as the other component in such a 3D architecture, as the functional groups in GO allow favorable interactions with ligands in MOFs. As a result of the integration of 2D GO, additional gas adsorption sites (i.e., microporosity) can be generated in the composite. This is exemplified by the increase in accessible surface area (evaluated using Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area based on a N2 physisorption measurement at 77 K) [66], as shown in Table 2. Indeed, several MOF/GO composites that were not limited to ZIF-8/GO [67], HKUST-1/GO [68], MOF-5/GO [69] and NiDOBDC/GO [64] were successfully synthesized. It was reported that MOFs with a smaller crystal size (i.e., nanocrystals) are preferred to generate a more uniform 3D structure, leading to a substantial increase in the accessible surface area (Table 2).

Table 2. The syntheses of metal-organic framework/graphene oxide (MOF/GO) composites and their Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface areas.

|

Composites(a) |

Particle Size of MOF (nm) |

SBET (m2/g) |

% Increment in SBET(b) |

Ref. |

|

HKUST-1/1% rGO |

- |

1677 |

21.3 |

[70] |

|

HKUST-1/16% GO |

micron-sized |

1550 |

3.3 |

[64] |

|

HKUST-1/9% GO |

10–40 |

1532 |

17.4 |

[68] |

|

HKUST-1/9% GO |

50 |

1002 |

10.2 |

[71] |

|

HKUST-1/5% GO |

- |

1362 |

14.7 |

[72] |

|

MIL-100/4% GO |

- |

1464 |

3.6 |

[73] |

|

MOF-5/10% GO |

50 |

806 |

1.6 |

[69] |

|

MOF-5/5% B-GO |

220–260 |

810 |

1.1 |

[74] |

|

MOF-505/5% GO |

micron-sized |

1279 |

16.2 |

[75] |

|

NiDOBDC/10% GO |

20–35 |

1190 |

26.6 |

[76] |

|

ZIF-8/1% GO |

100–150 |

819 |

−26.9 |

[67] |

(a) The % indicated corresponds to weight percentage. (b) Percentage change is calculated with reference to the BET surface area of a pristine MOF. rGO: reduced graphene oxide.

3. Performance of a Graphene-based Membrane

3.1. Investigation of the Membrane’s Performance in H2 Separation

Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 summarize the performances of graphene-based membranes in various gas separations involving H2 (H2/CO2, H2/N2 and H2/CH4), as reported in the literature. These tables show the properties of the selective layer (material and membrane thickness), type of membrane support, permeation testing conditions and the gas permeation properties (in terms of H2 permeance and gas selectivity). For the ease of comparison, H2 permeances of all membranes are reported in gas permeation unit (GPU), with 1 GPU = 10−6 cm3 (STP) cm−2 s−1 cmHg−1. In general, most graphene-based membranes reported are in the integrally skinned asymmetric (ISA) structure, whereas symmetric (dense) membranes are formed if graphene is served as the filler dispersed in polymer matrices [7].

Table 3. Performance of graphene-based membranes in H2/CO2 separation reported in the literature.

|

Membrane(a) |

Measurement Conditions |

H2 Permeance (GPU) |

H2/CO2 Selectivity |

Year (Ref.) |

||

|

Selective Layer |

Thickness (nm) |

Support |

||||

|

GO (spin-casting) |

5 |

PES5 |

- (pure gas, dry feed) |

25 |

0.2 |

13′ [77] |

|

GO (spin-casting) |

5 |

PES5 |

- (pure gas, humidified feed) |

12 |

0.1 |

13′ [77] |

|

GO (spin-coating) |

5 |

PES5 |

- (pure gas, dry feed) |

35 |

35 |

13′ [77] |

|

GO (spin-coating) |

5 |

PES5 |

- (pure gas, humidified feed) |

8.5 |

0.3 |

13′ [77] |

|

GO |

1.8 |

Al2O3 |

20 °C, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

328 |

2500 |

13′ [78] |

|

GO |

9 |

Al2O3 |

20 °C, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

343 |

3500 |

13′ [78] |

|

GO |

18 |

Al2O3 |

20 °C, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

358 |

2000 |

13′ [78] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) |

0.345 |

PMMA |

- (pure gas) |

2.99 × 107 |

4 |

14′ [79] |

|

GO(b) |

- |

Al2O3 |

H2/CO2 (1:1) |

7 |

5.7 |

14′ [80] |

|

ZIF-8@GO(b) |

- |

Al2O3 |

H2/CO2 (1:1) |

44 |

5.2 |

14′ [80] |

|

ZIF-8@GO |

100 |

Al2O3 |

250 °C, 1 bar, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

433 |

14.9 |

14′ [80] |

|

GO_M1_20 |

20,000 |

MCE |

- (pure gas) |

1.4 |

4.7 |

15′ [81] |

|

GO_M3_20 |

20,000 |

MCE |

- (pure gas) |

2.4 |

3.5 |

15′ [81] |

|

GO/ZIF-8 |

20 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

280 |

633 |

16′ [82] |

|

GO/ZIF-8 |

20 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

240 |

406 |

16′ [82] |

|

GO (vacuum filtration) |

- |

Al2O3 |

RT, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

1513 |

48 |

16′ [83] |

|

GO (vacuum filtration) |

- |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

1746 |

58 |

16′ [83] |

|

GO (spin-coating) |

20 |

Al2O3 |

RT, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

985 |

232 |

16′ [83] |

|

GO (spin-coating) |

20 |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

1045 |

259 |

16′ [83] |

|

GO |

890 |

Al2O3 |

2 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

- |

5 |

16′ [84] |

|

EFDA-GO |

890 |

Al2O3 |

2 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

1326 |

28 |

16′ [84] |

|

EFDA-GO |

890 |

Al2O3 |

-, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

876 |

17.2 |

16′ [84] |

|

GO-0.5 |

1000 |

Al2O3 |

1 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

81 |

20.9 |

17′ [85] |

|

GO |

230 |

YSZ |

20 °C (pure gas) |

133 |

111 |

17′ [86] |

|

GO |

2340 |

MCE |

25 °C (pure gas) |

2 |

2.0 |

17′ [87] |

|

GOU (U: UiO-66-NH2) |

1900 |

MCE |

25 °C (pure gas) |

116 |

6.4 |

17′ [87] |

|

GO/U (U: UiO-66-NH2) |

4100 |

MCE |

25 °C (pure gas) |

57 |

2.7 |

17′ [87] |

|

GO (T-30)(c) |

320 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas, dry feed) |

400 |

15.0 |

17′ [88] |

|

GO (T-30)(c) |

320 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas, humidified feed) |

313 |

10.5 |

17′ [88] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) |

0.345 |

AAO |

- (pure gas) |

4179 |

5.16 |

17′ [89] |

|

GO |

- |

α-Al2O3 |

RT, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

127 |

17.3 |

18′[90] |

|

GO(b) |

- |

γ-Al2O3 |

3 bar, 20 °C (pure gas) |

1761 |

38.5 |

18′ [91] |

|

GO |

- |

Nylon |

- (pure gas) |

18,507 |

15 |

18′ [92] |

|

CuO NS@GO-4 |

200 |

Nylon |

- (pure gas) |

22,687 |

18 |

18′ [92] |

|

HKUST-1@GO-4 |

200 |

Nylon |

- (pure gas) |

4478 |

84 |

18′ [92] |

|

HKUST-1@GO-4 |

200 |

Nylon |

-, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

1722 |

73.2 |

18′ [92] |

|

GO-EDA-0 |

- |

α-Al2O3 |

RT, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

339 |

11.6 |

18′ [90] |

|

GO-EDA-1 |

- |

α-Al2O3 |

RT, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

67 |

20.0 |

18′ [90] |

|

GO-EDA-2 |

- |

α-Al2O3 |

RT, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

73 |

22.9 |

18′ [90] |

|

GO-Zn2(bim)4-ZnO |

200 |

α-Al2O3 |

1 bar (pure gas) |

448 |

106 |

18′ [93] |

|

GO-Zn2(bim)4-ZnO |

200 |

α-Al2O3 |

1 bar. H2/CO2 (1:1) |

448 |

89 |

18′ [93] |

|

MEM-F200 |

500 |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

159 |

35.3 |

18′ [94] |

|

MEM-L1 |

200 |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

397 |

35.3 |

|

|

MEM-L1 |

200 |

PETE |

RT, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

340 |

22.5 |

18′ [95] |

|

MEM-S1 |

- |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

546 |

24.7 |

18′ [95] |

|

MEM-S1 |

- |

PETE |

RT, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

475 |

16.6 |

18′ [95] |

|

MEM-S250 |

500 |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

169 |

26.4 |

18′ [94] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) (M8) |

0.345 |

Macroporous support |

25 °C (pure gas) |

17 |

7.4 |

18′ [97][96] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) (M2) |

0.345 |

Macroporous support |

25 °C, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

100 |

5.8 |

18′ [97][96] |

|

GO(b) |

300 |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

134 |

44 |

19′ [98][97] |

|

GO-SDBS(b) |

334 |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

239 |

337 |

19′ [98][97] |

|

GO-B (B: Brodie) |

200 |

Polyester |

RT (pure gas) |

141 |

80.7 |

19′ [99][98] |

|

GO-H (H: Hummer) |

200 |

Polyester |

RT (pure gas) |

399 |

35.3 |

19′ [99][98] |

|

GO(b) |

470 |

Sil-1-Al2O3 |

1 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

358 |

62 |

19′ [100][99] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) (M9) |

0.345 |

Macroporous W support |

30 °C (pure gas) |

1200 |

3 |

19′ [101][100] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) (M9) |

0.345 |

Macroporous W support |

30 °C, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

1200 |

3 |

19′ [101][100] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) |

0.345 |

Stainless steel mesh |

- (pure gas) |

1.55 × 108 |

5.8 |

|

|

Graphene (2 layer) |

0.69 |

Stainless steel mesh |

- (pure gas) |

3.88 × 107 |

6.1 |

19′ [102][101] |

|

Graphene (4 layer) |

1.38 |

Stainless steel mesh |

- (pure gas) |

2.09 × 107 |

8.9 |

19′ [102][101] |

|

GO |

20,000 |

MCE |

- (pure gas) |

1800 |

4.2 |

20′ [104][102] |

|

rGO190 |

20,000 |

MCE |

- (pure gas) |

2100 |

9.4 |

20′ [104][102] |

|

GO |

240 |

Nylon |

1 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

49 |

5.9 |

20′ [41] |

|

GO-Co2+ |

240 |

Nylon |

1 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

60 |

6.4 |

20′ [41] |

|

GO-La3+ |

240 |

Nylon |

1 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

90 |

8.7 |

20′ [41] |

|

GO-500 |

41 |

Al2O3 |

1.5 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

94 |

9.1 |

20′ [105][103] |

|

CGO-76 |

53 |

Al2O3 |

1.5 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

52 |

21 |

20′ [105][103] |

|

LCGO-40 (LC: L-cysteine) |

- |

Al2O3 |

1.5 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

42 |

12 |

20′ [105][103] |

|

GO |

- |

Nylon |

1.2 bar, 25 °C, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

11,600 |

9 |

20′ [106][104] |

|

SOD/GO-M1 |

900 |

Nylon |

1.2 bar, 25 °C, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

1050 |

105 |

20′ [106][104] |

(a) All membrane configurations are indicated as flat sheets unless stated. (b) Self-supporting membrane. (c) Hollow fiber. GPU: gas permeation unit, RT: room temperature and PES5: polyethersulfone.

Table 4. Performance of graphene-based membranes in H2/N2 separation reported in the literature.

|

Membrane(a) |

Measurement Conditions |

H2 Permeance (GPU) |

H2/N2 Selectivity |

Year (Ref.) |

||

|

Skin Layer |

Thickness (nm) |

Support |

||||

|

GO |

1.8 |

Al2O3 |

20 °C, H2/N2 (1:1) |

328 |

220 |

13′ [78] |

|

GO |

9 |

Al2O3 |

20 °C, H2/N2 (1:1) |

343 |

300 |

13′ [78] |

|

GO |

18 |

Al2O3 |

20 °C, H2/N2 (1:1) |

358 |

1000 |

13′ [78] |

|

GO(b) |

- |

Al2O3 |

H2/CO2 (1:1) |

8 |

18.9 |

14′ [80] |

|

ZIF-8@GO(b) |

- |

Al2O3 |

H2/CO2 (1:1) |

46 |

10.7 |

14′ [80] |

|

ZIF-8@GO |

100 |

Al2O3 |

250 °C, 1 bar, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

433 |

90.5 |

14′ [80] |

|

GO_M1_20 |

20,000 |

MCE |

- (pure gas) |

1.4 |

3.5 |

15′ [81] |

|

GO_M3_20 |

20,000 |

MCE |

- (pure gas) |

2.4 |

6.9 |

15′ [81] |

|

GO/ZIF-8 |

20 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

280 |

88 |

16′ [82] |

|

GO/ZIF-8 |

20 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT, H2/CO2 (1:1) |

218 |

155 |

16′ [82] |

|

GO (vacuum filtration) |

- |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

1746 |

65 |

16′ [83] |

|

GO (spin coating) |

20 |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

1045 |

292 |

16′ [83] |

|

GO |

890 |

Al2O3 |

0.2 MPa, 25 °C (pure gas) |

- |

3.0 |

16′ [84] |

|

EFDA-GO |

890 |

Al2O3 |

0.2 MPa, 25 °C (pure gas) |

1123 |

7.5 |

16′ [84] |

|

GO[c] |

230 |

YSZ |

20 °C (pure gas) |

133 |

64 |

17′ [86] |

|

GO |

2340 |

MCE |

25 °C (pure gas) |

2 |

4.0 |

17′ [87] |

|

GOU (U: UiO-66-NH2) |

1900 |

MCE |

25 °C (pure gas) |

116 |

9.8 |

17′ [87] |

|

GO/U (U: UiO-66-NH2) |

4100 |

MCE |

25 °C (pure gas) |

57 |

7.0 |

17′ [87] |

|

GO (T-30)(c) |

320 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas, dry feed) |

400 |

7.2 |

17′ [88] |

|

GO (T-30)(c) |

320 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas, humidified feed) |

313 |

7.3 |

17′ [88] |

|

GO |

- |

Nylon |

- (pure gas) |

18,507 |

18 |

18′ [92] |

|

CuO NS@GO-4 |

200 |

Nylon |

- (pure gas) |

22,687 |

21 |

18′[92] [92] |

|

HKUST-1@GO-4 |

200 |

Nylon |

- (pure gas) |

4478 |

54 |

18′ [92] |

|

GO(b) |

- |

γ-Al2O3 |

3 bar, 20 °C (pure gas) |

1761 |

16.5 |

18′ [91] |

|

GO-Zn2(bim)4-ZnO |

200 |

α-Al2O3 |

1 bar (pure gas) |

448 |

126 |

18′ [93] |

|

GO-Zn2(bim)4-ZnO |

200 |

α-Al2O3 |

1 bar. H2/N2 (1:1) |

448 |

103 |

18′ [93] |

|

MEM-F200 |

500 |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

159 |

31.5 |

18′ [94] |

|

MEM-L1 |

200 |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

397 |

29.6 |

18′ [95] |

|

MEM-S1 |

- |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

546 |

18.3 |

18′ [95] |

|

MEM-S250 |

500 |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

169 |

23.7 |

18′ [94] |

|

GO(b) |

300 |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

134 |

36 |

19′ [97] |

|

GO(b) |

470 |

Sil-1-Al2O3 |

1 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

358 |

50 |

19′ [99] |

|

GO(b) |

470 |

Sil-1-Al2O3 |

1 bar, 20 °C, H2/N2 (1:1) |

328 |

40.7 |

19′ [99] |

|

GO-SDBS(b) |

334 |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

239 |

44 |

19′ [97] |

|

GO-B |

200 |

Polyester |

RT (pure gas) |

141 |

60.1 |

19′ [99][98] |

|

GO-H |

200 |

Polyester |

RT (pure gas) |

399 |

31.5 |

19′ [99][98] |

(a) All membrane configurations are indicated as flat sheets unless stated. (b) Self-supporting membrane. (c) Hollow fiber.

Table 5. Performance of graphene-based membranes in H2/CH4 separation reported in the literature.

|

Membrane(a) |

Measurement Conditions |

H2 Permeance (GPU) |

H2/CH4 Selectivity |

Year (Ref.) |

||

|

Skin Layer |

Thickness (nm) |

Support |

||||

|

GO(b) |

- |

Al2O3 |

H2/CH4 (1:1) |

8 |

38.4 |

14′ [80] |

|

ZIF-8@GO(b) |

- |

Al2O3 |

H2/CH4 (1:1) |

44 |

12.8 |

14′ [80] |

|

ZIF-8@GO |

100 |

Al2O3 |

250 °C, 1 bar, H2/CH4 (1:1) |

433 |

139.1 |

14′ [80] |

|

GO_M3_20 |

20,000 |

MCE |

- (pure gas) |

2.4 |

5.6 |

15′ [81] |

|

GO/ZIF-8 |

20 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

280 |

162 |

16′ [82] |

|

GO/ZIF-8 |

20 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT, H2/CH4 (1:1) |

218 |

355 |

16′ [82] |

|

GO (vacuum filtration) |

- |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

1746 |

29.3 |

16′ [83] |

|

GO (spin coating) |

20 |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

1045 |

194 |

16′ [83] |

|

GO (8 wt%)/PSF(c) |

50,000 |

- |

35 °C (pure gas) |

0.1 |

28 |

17′ [105] |

|

GO(30)_UiO-66 |

50,000 |

- |

35 °C (pure gas) |

0.32 |

68 |

17′ [107][105] |

|

GO (8 wt%)/PI(c) |

50,000 |

- |

35 °C (pure gas) |

0.26 |

81 |

17′ [107][105] |

|

GO(30)_UiO-66 |

50,000 |

- |

35 °C (pure gas) |

0.94 |

140 |

17′ [107][105] |

|

GO |

230 |

YSZ |

20 °C (pure gas) |

133 |

53 |

17′ [86] |

|

GO (T-30)(d) |

320 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas, dry feed) |

400 |

6.4 |

17′ [88] |

|

GO (T-30)(d) |

320 |

α-Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas, humidified feed) |

313 |

6.5 |

17′ [88] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) |

0.345 |

AAO |

- (pure gas) |

4179 |

3.17 |

17′ [89] |

|

GO |

- |

Nylon |

- (pure gas) |

18,507 |

3 |

18′ [92] |

|

CuO NS@GO-4 |

200 |

Nylon |

- (pure gas) |

22,687 |

4 |

18′ [92] |

|

HKUST-1@GO-4 |

200 |

Nylon |

- (pure gas) |

4478 |

35 |

18′ [92] |

|

GO-Zn2(bim)4-ZnO |

200 |

α-Al2O3 |

1 bar (pure gas) |

448 |

256 |

18′ [93] |

|

GO-Zn2(bim)4-ZnO |

200 |

α-Al2O3 |

1 bar. H2/CH4 (1:1) |

448 |

221 |

18′ [93] |

|

MEM-L1 |

200 |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

397 |

16.6 |

18′ [95] |

|

MEM-S1 |

- |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

546 |

11.4 |

18′ [95] |

|

MEM-F200 |

500 |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

159 |

15.7 |

18′ [94] |

|

MEM-S250 |

500 |

PETE |

RT (pure gas) |

169 |

12.5 |

18′ [94] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) (M5) |

0.345 |

Macroporous support |

25 °C (pure gas) |

210 |

12.8 |

18′ [96] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) (M2) |

0.345 |

Macroporous support |

25 °C, H2/CH4 (1:1) |

100 |

11 |

18′ [96] |

|

GO(c) |

300 |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

134 |

14.5 |

19′ [97] |

|

GO-SDBS |

334 |

Al2O3 |

RT (pure gas) |

239 |

20.5 |

19′ [97] |

|

GO(c) |

470 |

Sil-1-Al2O3 |

1 bar, 25 °C (pure gas) |

358 |

28 |

19′ [99] |

|

GO-B |

200 |

Polyester |

RT (pure gas) |

141 |

27.7 |

19′ [98] |

|

GO-H |

200 |

Polyester |

RT (pure gas) |

399 |

15.7 |

19′ [98] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) (M4) |

0.345 |

Macroporous W support |

30 °C (pure gas) |

1000 |

5.1 |

19′ [108][106] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) (M9) |

0.345 |

Macroporous W support |

30 °C (pure gas) |

1200 |

16 |

19′ [100] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) (M9) |

0.345 |

Macroporous W support |

30 °C, H2/CH4 (1:1) |

1200 |

16 |

19′ [100] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) |

0.345 |

Stainless steel mesh |

- (pure gas) |

1.55 × 108 |

2.5 |

19′ [101] |

|

Graphene (2 layers) |

0.69 |

Stainless steel mesh |

- (pure gas) |

3.88 × 107 |

2.3 |

19′ [101] |

|

Graphene (4 layers) |

1.38 |

Stainless steel mesh |

- (pure gas) |

2.09 × 107 |

3.0 |

19′ [101] |

|

Graphene (1 layer) |

0.345 |

Nanoporous carbon (NPC) |

- (pure gas) |

1090 |

9.5 |

20′ [109][107] |

(a) The membrane configurations are flat sheets unless stated. (b) Self-supporting membrane. (c) The values are reported in barrer (dense flat sheet membrane), where 1 barrer = 10−10 cm3 (STP) cm cm−2 s−1 cmHg−1. Nevertheless, the values in the table are converted to GPU for an effective comparison. (d) Hollow fiber.

3.1.1. Single-layer Graphene

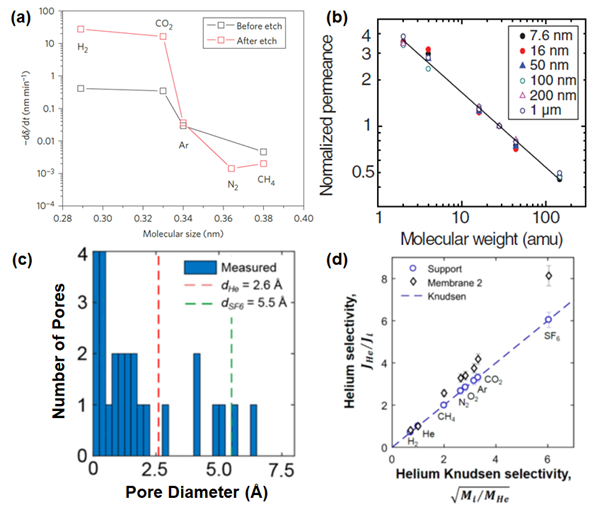

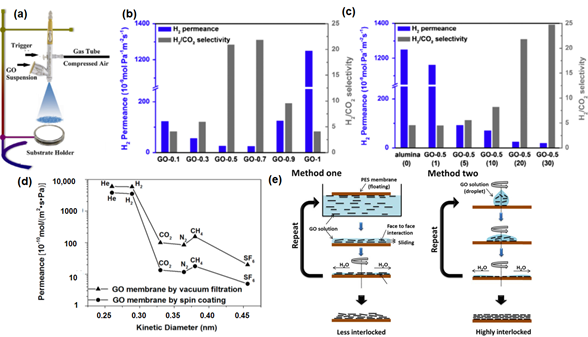

As mentioned in Section 2.1, the unique atomic thickness of graphene may open up a chance to achieve the highest flux, although a defect-free graphene sheet is impermeable to all gases. The successful formation of a single-layer graphene membrane typically involves two critical steps: (1) the transfer of large-area graphene onto a desired porous substrate without appreciable tears and cracks and (2) the creation of subnanometer pores with a narrow pore size distribution. The investigation of single-layer porous graphene for selective molecular transport was first conducted with the use of UV-induced oxidative etching of a graphene sheet on a porous SiO2 support. As reported by Koenig et al. [110][108], even though the gas permeance was not calculated in a precise manner, an investigation on the leak rate of porous the graphene formed by the etching process showcased its potential in H2/N2 and H2/CH4 separations, as shown in Figure 4a. This is subsequently followed by the utilization of focused ion beam (FIB) milling to generate pores on a single-layer graphene that was attached on a freestanding SiNx support. In this work, the transfer of dual-layer graphene sheets rather than single-layer graphene sheets was conducted in order to improve the stability of the free-standing graphene. The pores in two different ranges could be obtained with the use of gallium (Ga+) and helium (He+) ions, with the resulting pore sizes ranging from 10 nm to 1000 nm. With the overall porosity of a mere 4%, an extraordinarily high gas permeance could be achieved while the selectivity stayed at the Knudsen selectivity (Figure 4b) [79].

To overcome the limitation of the previous work, a porous graphene with pores in the subnanometer range needed to be developed, leading to a molecular sieving beyond the Knudsen selectivity. In the study conducted by Boutilier et al. [89], a single-layer graphene possessing a large amount of permeable pores was produced at the centimeter scale. An observation by aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) after bombarding gallium ions onto the surface of graphene revealed that the developed membrane possessed pores that can discriminate He (red-dotted line) from SF6 (green-dotted line) (Figure 4c). However, cracks could be formed in the single-layer graphene during the transfer onto a porous support, resulting in a separation performance that was merely close to the Knudsen selectivities for H2/CH4 (3.14) and H2/CO2 (5.16), respectively (Figure 4d). The possibility of the crack formation can be mitigated by employing the wet-transfer technique. This method allows an effective transfer of single-layer nanoporous graphene onto a wide range of substrates without jeopardizing the intrinsic selectivity. In addition, an oxidative etching technique (e.g., oxygen, oxygen plasma and ozone) was able to create pores under the resolution of a subnanometer range [96,100], leading to a gas separation performance of single-layer graphene surpassing the Knudsen selectivity of the desired gas pairs (e.g., H2/CH4). A recent study on developing a single-layer graphene membrane with the use of chemical vapor deposition (CVD) was reported by Rezaei et al. [107]. In this work, the copper (Cu) foil was used as the catalytic substrate. It has been observed that the H2/CH4 separation performance of single-layer graphene is heavily influenced by the intrinsic purity and uniformity of the Cu foil. Thus, to improve the potential feasibility of utilizing Cu foil in the large-scale fabrication of single-layer graphene, it was proposed to anneal the Cu foil at a temperature close to its melting point. Such a process reduces the overall surface roughness of the Cu foil, leading to a uniform growth of the graphene layer. In such a case, an improvement of the H2/CH4 selectivity by 1-to-1.5-fold can be achieved.

Figure 4 (a) Average deflection (-dδ/dt) against molecular size for a bilayer graphene membrane (Bi-3.4 Å). Reprinted with permission from Reference [110][108], copyright 2012, Nature Publishing Group. (b) The trend of gas permeability (permeance of H2, He, CH4, N2, CO2 and SF6 that is normalized with N2 permeance) for single-layer graphene with various average pore diameters. The solid line on the graph indicates the inverse square root of mass dependence (illustration of Knudsen selectivity). Reprinted with permission from Reference [79], copyright 2014, American Association for the Advancement of Science. (c) Pore size distribution of single-layer graphene measured with the aid of scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). (d) Ratio of the helium flow rate to those of other gases that is plotted against Knudsen selectivity. Reprinted with permission from Reference [89], copyright 2017, American Chemical Society.

3.1.2. Multi-layer Graphene

As elaborated in the previous section, several undesirable bottlenecks are expected in the development of defect-free single-layer graphene membranes. Particularly, it is still technically challenging to transfer a graphene layer onto a porous substrate while keeping a good integrity without defects and leaks [101]. Thus, alternatively, the fabrication multi-layer graphene laminates on porous substrates has been a major focus in the H2 separation process.

In general, one of the most common approaches in multi-layer graphene membrane fabrication is the vacuum filtration method. In the study by Romanos et al. [81], the membrane performance was investigated while varying several parameters, such as the filtration rate (controlling the downstream pressure), volume of GO suspension (thickness of the selective layer) and surface chemistry (GO and rGO). From the gas permeation data, a slower filtration rate led to a membrane showing molecular sieving characteristics. This is because a faster filtration rate generates a haphazard arrangement of GO stacks, resulting in a larger porosity. Besides, the gas permeation results indicated that a sufficient amount of GO suspension is required develop a highly selective membrane. Lastly, rGO often created undesirable membrane defects during the fabrication, as the reduction of GO gave a negative impact on the dispersibility in both water and organic solvent due to a decrease in hydrophilicity. The formation of rGO agglomerates are reported to be irreversible in spite of using a sonication process, which is typically adopted as an action to minimize aggregation between GO sheets .

The microscopic structure of the GO membrane fabricated via vacuum-filtration is reported to be unpredictable, even though the filtration rate is controlled. This is due to the fact that the unavoidable evaporation of solvent molecules results in the formation of the nonuniform (random) packing of GO sheets [110]. Owing to the absence of external forces, a heterogeneous layer with a loop structure (i.e., wrinkling) can be formed [111]. Furthermore, the vertical pulling force by vacuum filtration does not ensure a well-ordered horizontal alignment of GO nanosheets onto a porous membrane support [83]. To minimize such effects, Guan et al. [85] and Ibrahim et al. [94] fabricated GO laminate membranes by a spray evaporation-induced self-assembly approach (Figure 5a). Contrary to the conventional evaporation method, the spraying process utilizes ultra-small droplets, leading to a higher evaporation area. Apart from this, the capillary action between the substrate and GO, as well as hydrogen bonding (or van der Waals forces) between GO nanosheets during each spraying step, give rise to the separation layer with uniform thickness. Further investigation on the spraying conditions, including evaporation rate (Figure 5b) and spraying time (Figure 5c), was also conducted. As shown in Figure 5b, an excessive reduction of evaporation time led to the formation of wrinkles and random deposition of GO laminates, resulting in a high H2 permeance with a low H2/CO2 selectivity. A longer spraying time is typically required to achieve a uniform coverage of the substrate with GO laminates, resulting in a reasonably high H2/CO2 selectivity (Figure 5c).

Figure 5 (a) Schematic illustration of the spray evaporation process. Reprinted with permission from Reference [94], copyright 2018, Elsevier. (b) H2 separation performance of GO membranes with variations of the evaporation rate (0.1 to 1, based on the mass fraction of ethanol in an aqueous solution). (c) H2 separation performance of GO membranes with variations of the spraying time (time in this context refers to the number of spray coatings conducted, which is indicated in parentheses). Reprinted with permission from Reference [85], copyright 2017, Elsevier. (d) Comparison of the pure gas permeance of the GO membranes by spin coating and vacuum filtration. Reprinted with permission from Reference [83], copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (e) Comparison between the GO membranes prepared by method one (contacting the polyethersulfone (PES5) membrane with the GO solution, followed by spin coating) and method two (spin casting). Reprinted with permission from Reference [77], copyright 2013, American Association for the Advancement of Science.

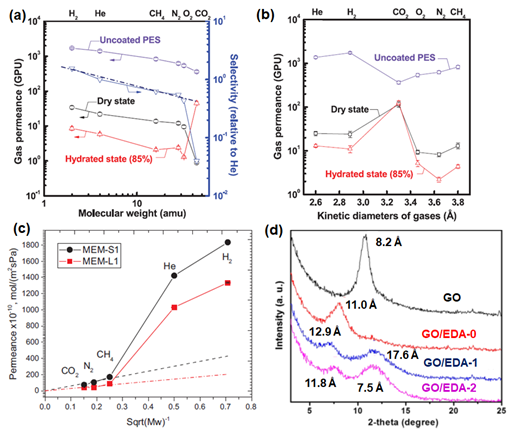

The fabrication of multi-layer GO laminates can also be conducted with the coating techniques. In general, the performance of GO membranes that were fabricated from spin coating is reported to be higher than that of membranes synthesized by the vacuum filtration method (Figure 5d), due to the creation of a more uniform structure without the formation of wrinkles. In the study by Kim et al. [77], GO coating was conducted by using both spin coating (method one) and spin casting (method two), as shown in Figure 5e. GO membranes fabricated by method one showed less interlocked structures in comparison to method two. Thus, not surprisingly, the separation performance of the GO membrane fabricated by method one is correlated to Knudsen selectivity (illustrated by the dashed line in Figure 6a). This is because the presence of edge-to-edge repulsion in GO nanosheets causes the formation of an island-like assembly in the GO laminates. Nevertheless, due to the potential formation of hydrogen bonding between CO2 and the polar groups in GO, a much lower CO2 permeance and higher H2/CO2 selectivity were reported (Table 3). On the other hand, in method two, both attractive and repulsive forces on GO nanosheets can be foreseen, as both casting and spinning processes occur simultaneously, leading to a highly interlocked structure in the resulting GO laminate. Consequently, a CO2-selective membrane (rather than a H2-selective membrane) can be successfully made by method two. Notably, an introduction of humidified feed gas resulted in a sacrificial decrease in gas permeance due to the blockage of the permeation channel between GO layers by condensed water molecules (Figure 6a,b). However, such a phenomenon was not prominent when CO2 was the dominant permeate gas, presumably due to the favorable interactions between CO2 and the condensed water molecules. As such, the GO membranes developed by method one (Figure 6a) were found to be CO2-selective rather than H2-selective.

Figure 6. (a) Gas permeation of the GO membranes (method one) as a function of molecular weight (the black dash line corresponds to the ideal Knudsen selectivity). (b) Gas permeation of the GO membranes (method two) as a function of the kinetic diameter. Reprinted with permission from Reference [77], copyright 2013, American Association for the Advancement of Science. (c) Pure gas permeation of MEM-S1. Reprinted with permission from Reference [95], copyright 2018, Elsevier. (d) X-ray diffraction (XRD) profiles of GO, GO/EDA-0, GO/EDA-1 and GO/EDA-2 (0, 1 and 2 refer to the crosslinking time in hours). Reprinted with permission from Reference [90], copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

Apart from this, the performance of GO membranes can be altered by employing GO with different flake sizes. In general, the in-house synthesis protocol typically produces GO sheets with small and irregular lateral dimensions, since such synthesis involves the exfoliation of GO layers based on a sonication process. Thus, with the variation of the sonication period, a wide distribution of the flake size can be caused [95]. This behavior often resulted in a nonuniform GO coverage or the formation of appreciable defects. To mitigate such a problem, a freeze-thaw exfoliation was utilized, leading to GO nanosheets of large dimension (~13 μm) [83]. The GO membranes fabricated by such large GO flakes showed a high selectivity due to the formation of a more tortuous diffusion path (Figure 6c), which was also observed in a recent work [95].

Another way to improve the separation performance of GO membranes is the alteration of the interlayer spacing (or d-spacing) of GO laminates. This spacing can be served as “slits” affecting the molecular transport in GO membranes [63]. Various intercalators that are not limited to metal ions, cations, amines and polymers [112-114] can be adopted into the interlayer spacing of the GO nanosheets through a crosslinking process. For example, Lin et al. [90] used ethylenediamine (EDA) as the crosslinker for the fabrication of GO membranes, as the carboxylic acid groups (–COOH) on GO allowed an effective attachment of EDA onto the GO sheets. The crosslinking in-between EDA and GO can be conducted while varying the reaction time (GO/EDA-0, GO/EDA-1 and GO/EDA-2). The insertion of EDA in-between the GO layers increased the interlayer spacing from 8.2 Å to 11 Å (Figure 6d). This resulted in a 166% increase in the H2 permeance but a 33% decrease in the H2/CO2 selectivity with respect to the performance of the pure GO membrane. On the other hand, due to the presence of smaller d-spacing with the increase in crosslinking time, a substantial decrease in the H2 permeance (−47%) with an increase in H2/CO2 selectivity (15%) was observed for the GO/EDA-1 membrane. A similar result was also reported by Cheng et al. [103]. In this study, it was reported that an optimal amount of crosslinker (cysteamine in this study) was required to prevent the formation of extraordinary large interlayer spacing, which decreased the overall H2/CO2 selectivity. In a recent study by Chuah et al. [41], different cations (Co2+ and La3+) were intercalated in between GO nanosheets to tune the interlayer spacing. The gas separation performance indicated that the incorporation of cations is feasible to increase the H2 permeance due to the increase in interlayer spacing (8.5 Å for GO-Co2+ and 8.8 Å for GO-La3+) in comparison to pure GO (8.8 Å). The H2/CO2 selectivities of GO-Co2+ and GO-La3+ are reported to be considerably higher than that of pure GO, which is potentially attributed to the presence of chemical interactions between metal ions (Co2+ and La3+) and CO2 molecules.

Furthermore, the interlayer spacing of GO nanosheets can be varied by adjusting the synthesis method of GO. The modified Hummers’ method (GO-H) is most common in the synthesis of GO flakes due to the rapid graphite oxidation [115]. However, it is considerably challenging to decrease the interlayer spacing of the GO membrane to a value smaller than 8.8 Å for this case. Therefore, the development of GO membranes with the use of GO nanosheets that are synthesized from the modified Brodie’s method (GO-B) was explored by Ibrahim et al. [116]. It was observed that GO-B membranes can be fabricated with a much smaller interlayer spacing (6.0 Å) in comparison to GO-H, leading to more effective molecular sieving. From the gas permeation testing [98], the increases in H2/CO2, H2/N2 and H2/CH4 selectivities by 129%, 91% and 76%, respectively, were reported when GO-B was employed in the membrane fabrication instead of GO-H. However, it should be noted that this synthesis protocol is more complicated and tedious as compared to the Hummer’s method, since repetitive graphite oxidation is required (typically about three ~ four times) to obtain the desired product (C/O ratio > 2).

Last, but not least, the fabrication of large-scale multi-layer graphene laminate membranes has been demonstrated. The flat sheet configuration that is commonly reported in the literature (summarized in Tables 3, 4 and 5) is not a popular choice in practical gas separations due to the limited membrane area per unit volume. Rather, the hollow fiber or capillary configuration that provides a high surface area-to-volume ratio is more frequently chosen. In this context, a dip coating by soaking hollow fiber membrane supports into a GO dispersion has been tried, with the lumen side being connected to a mild vacuum to mimic the vacuum filtration method, as in flat sheet membrane fabrication. Such an approach is often termed as the vacuum suction method [86,88,91,97,99]. Nevertheless, the optimization of selective layer thickness is known to be difficult, since an increase in the GO coating time may not result in a linear increase in the thickness of GO laminates. This is because the deposited GO layers serve as undesirable resistances inhibiting the additional stacking of GO sheets on the hollow fiber supports [88].

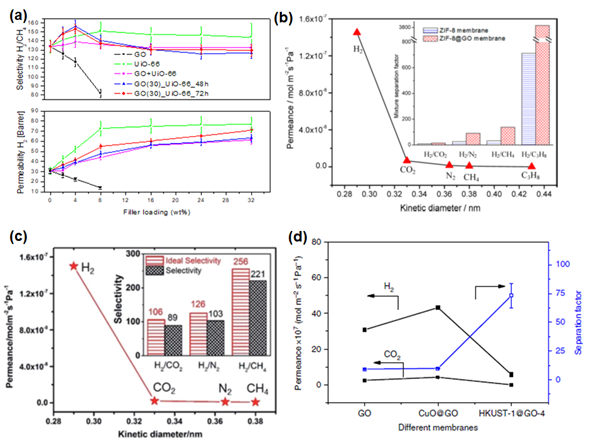

3.1.3. Graphene-based Composites

The potential utility of GO in altering the H2 separation performance of polymer membranes (in polysulfone and Matrimid® 5218) was investigated by Castarlenas et al. [105]. Based on the gas permeation data, at the GO loadings of 4 wt% and 8 wt%, undesirable decreases in both H2 permeability (c.a. 140% and 100%, respectively) and H2/CH4 selectivity (c.a. 50% and 38%, respectively), were observed (Figure 7a). This behavior is attributed to the nonporous nature of GO creating tortuous diffusion pathways in the membrane [117]. Besides, the decrease in H2/CH4 selectivity is plausibly attributed to a higher polarizability of CH4 [51] than H2 (Table 1), leading to a more favorable sorption of CH4 in the membrane over H2. Rather, these membranes were found to be more suitable in CO2/CH4 separation, as evidenced by a gradual increase in mixed-gas selectivity with the increase in GO loading [47,65]. Hence, the incorporation of a GO/MOF composite filler has been tried to improve the H2 separation performance, since such a composite filler not only has a high porosity but, also, minimizes the aggregation of MOFs [118] [30,118]. Such an idea was verified by comparing the H2/CH4 separation performance of MMMs comprising (1) UiO-66/GO composites and (2) the physical blending of UiO-66 and GO [105]. Based on the gas permeation results, enhancements in both H2 permeability and H2/CH4 selectivity were observed for the case of UiO-66/GO composites (Figure 7a), which also showed a good interfacial interaction between the filler and polymer matrix. In contrast, the physical blending was found to be less effective in improving H2/CH4 selectivity.

One of the major advantages of constructing a 3D architecture membrane with MOF and GO was reported to be a reduction of membrane defects. As mentioned in the previous section, wrinkles can be formed in GO laminates that are fabricated via vacuum filtration. Besides, the creation of a smooth continuous GO layer can be challenging if the solvent used does not form a good GO dispersion. Thus, Huang et al. [80] developed a bi-continuous ZIF-8@GO membrane by using layer-by-layer assembly. GO in this membrane serves as the sealant to fill the gaps in the ZIF-8 membrane. Owing to the presence of capillary forces between GO and ZIF-8, the gas molecules are expected to diffuse dominantly through the micropores in ZIF-8, leading to an extraordinary high H2 permeance and decent H2/CO2, H2/N2 and H2/CH4 selectivities (Figure 7b). The ZIF-8@GO composite membranes without appreciable defects were also made by sealing the gaps in GO membranes with ZIF-8 crystals grown in the defective region [82]. Gas permeation testing revealed that the deposition of ZIF-8 onto defective graphene layers can improve the H2 permeance by 5.4 times (Table 5). In a subsequent study by Jia et al. [87], the deposition of UiO-66-NH2 (presynthetic modification UiO-66 with a 2-aminoterephtalitc acid ligand) and GO was conducted in two different ways: (1) simultaneous deposition of UiO-66-NH2 and GO onto the support (GOU@S) and (2) layer-by-layer deposition of UiO-66-NH2 and GO onto the support (GO/U@S). The performances of both GOU@S and GO/U@S in H2/CO2 and H2/N2 separations were improved substantially as compared to GO@S due to the presence of hydrogen bonding and electrostatic force that eliminated the formation of nonselective voids. Nevertheless, the performance of GOU@S was more promising than GO/U@S due to the better integrity of the overall membrane structure (Figure 7c).

In general, ZIF-8 and UiO-66 (and its derivative) are commonly used in membrane fabrication due to their scalable synthesis and decent stability under humid conditions. Nevertheless, other MOF-based composites have also been synthesized using HKUST-1 particles and Zn2(bim)4 nanosheets, as reported by Kang et al. [92] and Li et al. [93], respectively. Both membranes are developed based on similar protocols. First, a thin layer of metal oxide nanoparticles was prepared on the surface of a tubular support. This is followed by the addition of GO and the respective ligand to conduct an in-situ transformation into MOF@GO composites. The membrane comprising Zn2(bim)4 nanosheets exhibited a molecular sieving property (Figure 7d), as evidenced by high H2/CO2, H2/N2 and H2/CH4 selectivities in Tables 3, 4 and 5 [93]. The HKUST-1 crystals are also able to improve the H2/CO2 selectivity from 12.2 to 73.2. However, a sharp decrease in H2 permeance was accompanied, which is not commonly encountered in previous studies. Such a deviation could be attributed to the uneven distribution or arrangement of HKUST-1 bulk crystals in comparison to Zn2(bim)4 nanosheets. Nevertheless, subsequent tuning of the selective layer through the variation of filtration cycles proved that H2/CO2 separation performance can be optimized by controlling the thickness of the selective layer.

Meanwhile, other materials can also be used as the pillar to synthesize GO-based composites. For example, in a recent study conducted by Guo et al. [104], hydroxy sodalite (SOD) nanocrystals were impregnated into GO layers to design a H2-selective membrane. The incorporation of SOD nanocrystals increased the H2/CO2 selectivity from 9 to 105, due to the small pore aperture (2.9 Å) of SOD. Nonselective defects were not formed due to the strong hydrogen bonding between SOD and GO, which was confirmed by the shifting of the O–H band from 1641 cm−1 to 1600 cm−1 in the Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis.

Figure 7. (a) Performance of the mixed-matrix membrane (MMM) with the incorporation of GO, UiO-66 and UiO-66/GO composites (GO_UiO-66) and the physical blending of GO and UiO-66 (GO + UiO-66). Reprinted with permission from Reference [105], copyright 2017, Elsevier. (b) Single-gas permeance (at 250 °C) of the ZIF-8@GO membrane as a function of the kinetic diameter. The inset includes the selectivities of the ZIF-8 and ZIF-8@GO membranes. Reprinted with permission from Reference [80], copyright 2014, American Chemical Society. (c) Single-gas permeance of the GO-Zn2(bim)4 membrane. The inset includes the ideal and mixed-gas selectivities. Reprinted with permission from Reference [93], Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0. (d) Mixed-gas H2/CO2 separation performance of the GO membrane, CuO@GO membrane and HKUST-1@GO-4 membrane. Reprinted with permission from Reference [92], Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0.

3.2. Molecular Simulation and Modeling

3.2.1. Single-layer Graphene

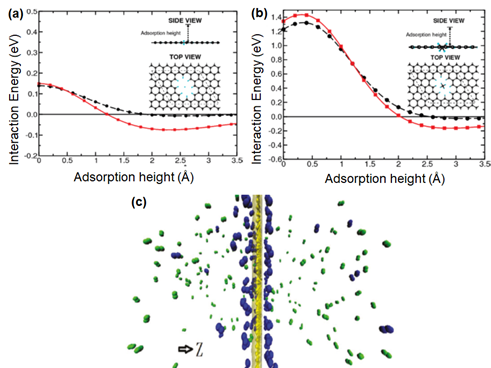

As discussed in Section 2.1, the pore formation is of paramount importance in order to induce the transport of atoms or molecules through graphene layers . Thus, several computational studies to investigate the effect of pore size on the separation performance have been reported. The propensity of single-layer graphene in H2 separation was first studied by Jiang et al. [120] with the aid of DFT. Such calculations can be employed to determine the energy barriers for the transport of gaseous molecules through the porous graphene. As shown in Figure 8a,b, the energy barriers for H2 and CH4 transports through a porous graphene with 2.5-Å pores are calculated to be 0.22 and 1.60 eV, respectively. Considering the fact that 0.22 eV of the energy barrier for H2 can be readily overcome under ambient conditions, a high H2/CH4 selectivity is predicted.

Subsequently, the performance of porous graphene in H2/N2 separation was studied while varying the sizes and shapes of the pores [121], with the use of MD simulation. MD is generally useful to predict the physical movement of molecules as a function of time. Two different optima corresponding to the maximum H2/N2 and N2/H2 selectivities could be observed when the pore size was gradually increased. This is because the adsorption of N2 on the graphene’s surface is preferred over H2 (Figure 8c), although the size of H2 is much smaller than N2 [51]. This phenomenon resulted in a more effective diffusion of N2 molecules if the pore size was sufficiently larger than the size of N2. Meanwhile, the surface property of porous single-layer graphene may govern the resulting gas transport behavior, as reported by Drahushuk et al. [122] and Tao et al. [123]. For example, CO2, which possess the highest polarizability (Table 1) as compared to commonly reported gases (N2, H2, He and CH4), is strongly bound to the graphene surface rich in polar functionality, thus resulting in a poor CO2 diffusivity and a high H2/CO2 selectivity [101]. However, it should be noted that the practical feasibility of single-layer graphene is typically hampered by its strong susceptibility to defect formations. For instance, the diffusion barrier for CH4 permeation through a single-layer graphene decreases to 0.02 eV at the pore size of 3.8 Å and 0 eV at 5.0 Å, respectively, from 1.60 eV at 2.5 Å [119][120].

Figure 8. Interaction energy between (a) H2 and (b) CH4 and all-hydrogen passivated porous graphene as a function of the adsorption height. The red and black lines are referring to density functional theory (DFT) calculations conducted by the van der Waals density functional (vdW-DF) and Perdew, Burke and Erzenhoff functional (PBE), respectively. Reprinted with permission from Reference [120], copyright 2009, American Chemical Society. (c) Gas distribution of N2 (green) and H2 (blue) on the porous graphene surface. Reprinted with permission from Reference [121], copyright 2013, American Chemical Society.

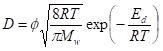

3.2.2. Multi-layer Graphene

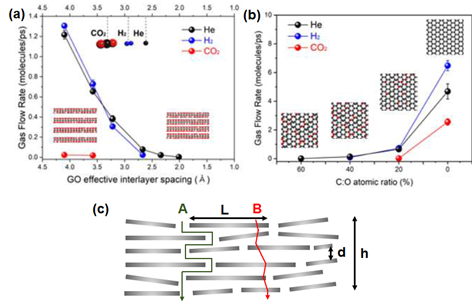

Computational work on multi-layer graphene membranes typically studied the three different parameters, namely interlayer spacing between GO layers, oxidation degree and permeation conditions (temperature and pressure). In general, an increase in the interlayer spacing can increase the permeance across all gas molecules [102], as demonstrated in Figure 9a. This is evidently observed for the case of CO2, in which a noticeable flow is observed at interlayer spacings higher than 3.50 Å [51]. However, a decrease in H2 permeance can often be observed in mixed-gas permeations through a sufficiently large interlayer spacing due to the hindrance by competing molecules [111][124]. On the other hand, an increase in the oxidation degree (Figure 9b) leads to a substantial decrease in gas permeance. Such an effect is particularly noticeable for molecules with larger kinetic diameters owing to the increased steric hindrance by the GO surface [111][124]. It is also reported that the gas transport behavior in GO laminates can be influenced by the permeation conditions. In general, an increase in the simulation temperature resulted in an increase in the kinetic energy of the permeating H2 molecule, leading to a rapid H2 transport through the interlayer spacing of GO layers. Likewise, an increase in the operating pressure increases the collision frequency of the H2 molecules, resulting in an increase in H2 permeation [124].

Figure 9. (a) Effect of the change of the interlayer spacing (interlayer carbon-to-carbon system is varied from 4.75 Å to 7.50 Å) on the gas flow rate (gas permeance). (b) Effect of the variation of the oxidation degree (atomic ratio between C and O, in which a higher C:O refers to a higher oxidation degree) on the gas flow rate. Reprinted with permission from Reference [102], copyright 2020, Elsevier. (c) Gas transport model through a multi-layer graphene membrane. Adapted with permission from Reference [95], copyright 2018, Elsevier.

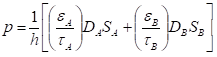

The gas transport properties of multi-layer graphene laminates have also been predicted using the semi-quantitative approach, assuming linear adsorption for all gases [94,95]. Such an assumption is typically valid for H2 (in comparison to N2, CH4 and CO2) under the reported conditions in Tables 3, 4 and 5. Considering the membrane configuration in Figure 9c, the pure gas permeance, p, can be expressed by Equation (1), where h = the overall thickness of GO, ε = porosity, τ = tortuosity, D = diffusivity and S = solubility. The subscripts A and B refer to the gas transport pathways, as depicted in Figure 9c. The diffusion rate, which is dependent on the kinetic diameter of the gas and pore size, can be calculated using Equation (2), where ϕ = the structure of the pore channel, Mw = molecular weight of the gas and Ed = activation energy for gas diffusion. In general, Ed can be neglected if the ratio between the kinetic diameter of the gas molecule and the pore diameter is less than 0.6. can be calculated by using the ratio of the GO sheet length and thickness (L/d), whereas can be assumed to be in unity if the flow through the defective GO sheets is a uniform, straight line. However, it should be noted that the calculation of ε is highly dependent on the structures of the GO sheet and resulting membrane.

|

|

(1) |

|

|

(2) |

3.2.3. Graphene-based Composites

|

|

(3) |

|

|

(4) |

The modeling studies of graphene-based composites are generally limited as compared to the theoretical models based on three-dimensional porous particles [7,125]. The gas permeation behavior of 2D fillers can be modeled using the equation proposed by Cussler [112][126]. In Equation (3), the gas permeability of MMM, PMMM, is related to the gas permeability of the polymeric membrane (P), the ratio of diffusion coefficients in the pure polymer and MMM (δ), aspect ratio of the flake (β) and volume fraction of the filler (β). It is noteworthy that the presence of nonidealities (e.g., sieve-in-a-cage, plugged sieve and rigidified interface) in MMM may give different results from the prediction by this equation [7].

Apart from this, the effectiveness of graphene in composite (or MMM) membranes can be quantified with the evaluation of the filler enhancement index (Findex). The Findex is an empirical metric to measure the effectiveness of a filler (graphene, in this context) in improving the gas separation performance after ruling out the effect of the polymer matrix. The calculation can be done using Equation (4), where η = the slope that is determined from the Robeson upper-bound limit, = the gas selectivity of MMM and α = the gas selectivity of the polymeric membrane. Based on the calculation results, a filler in MMM can be classified into “ideal”, “exemplary”, “competent”, “moderate” or “incompetent” categories [7]. However, this relationship is not applicable to the undesirable variations of membranes, such as physical aging and plasticization [113][114][23,127,128].

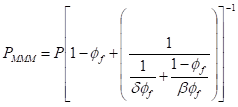

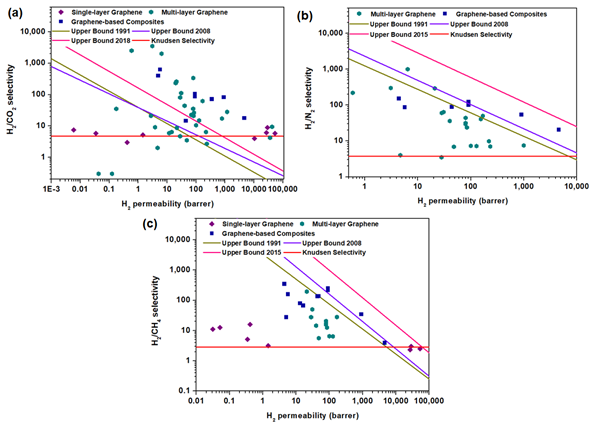

3.3. Comparison with Upper-Bound Limits

The current performances of graphene-based membranes were benchmarked against the upper-bound limits for conventional polymeric membranes. In order to reflect the intrinsic gas separation performance of the tested membrane, it is necessary to convert H2 permeance into H2 permeability using the thickness of the selective layer. Such plots for single-layer graphene, multi-layer graphene and graphene-based composites are shown in Figure 10. The detailed parameters used to draw the upper-bound limits are provided in Table 6. Noticeably, the H2/CO2 separation performance of graphene-based membranes could surpass the upper-bound limit due to the largest margin in the molecular weights of the gas molecules leading to the highest Knudsen selectivity, in contrast to H2/N2 and H2/CH4 separations. Besides, due to the interaction between CO2 possessing a high polarizability and the polar groups on graphene surfaces, the diffusion of CO2 can be inhibited, which leads to a decrease in CO2 permeance and, thus, an increase in H2/CO2 selectivity. Nevertheless, graphene membranes to date have not yet been effective to perform molecular sieving based on the kinetic diameters. In particular, single-layer graphene has been reported to be quite challenging to achieve a selectivity that is higher than the Knudsen selectivity due to its susceptibility to defect formations as compared to multi-layer graphene and graphene-based composites.

Figure 10. Comparison of the performances of single-layer graphene, multi-layer graphene and graphene-based composites (the data points are obtained from Tables 3–5) with the upper-bound limits for (a) H2/CO2, (b) H2/N2 and (c) H2/CH4 separations. The upper-bound curves are determined based on References [115][28,29,35,129] and summarized in Table 6.

Table 6. Summary of the upper bounds [115][28,29,35,129] used for H2 separation(a).

|

Upper Bound Curve |

Knudsen Selectivity |

1991 |

2008 |

2015 (2018)(b) |

|||

|

k (barrer) |

n |

k (barrer) |

n |

k (barrer) |

n |

||

|

H2/CO2 |

4.69 |

1200 |

−1.94 |

4515 |

−2.30 |

15,248(c) |

−1.89(c) |

|

H2/N2 |

3.74 |

52,918 |

−1.53 |

97,650 |

−1.48 |

1,100,000 |

−1.46 |

|

H2/CH4 |

2.83 |

18,500 |

−1.21 |

27,200 |

−1.11 |

195,000 |

−1.10 |

(a) The upper-bound curve can be constructed using , where P = permeability, α = selectivity and k and n are constants. (b) The latest H2/N2 and H2/CH4 upper-bound limits were constructed in 2015, whereas the latest H2/CO2 upper-bound limit was constructed in 2018. (c) The parameters (k and n) in the 2018 upper-bound limit for H2/CO2 separation were not furnished. The limit is determined based on interpolation of the available data points.

4. Conclusion and Future Perspective

In this review, the recent progress of graphene-based membranes in the field of H2 separation was discussed. Single-layer porous graphene has the potential to form a highly permeable membrane, as such a configuration renders the smallest transport resistance to permeating molecules. Nonetheless, such a configuration is hampered by its low scalability and high possibility of defect formation. Hence, multi-layer graphene and graphene-based composites are studied as promising alternatives, since the fabrications of these membranes are technically viable. Eventually, the major hurdle in utilizing graphene in gas separation membranes is its capability to translate the performance when a large-scale membrane is developed for practical industrial-scale operations.

In addition to the scalability, future efforts should be given to investigating graphene-based membranes under realistic conditions. First and foremost, the measurement of gas separation performances using mixed-gas is desirable as the competition between different gas molecules has a significant impact on the gas separation performance. In this context, the H2 separation performance of graphene-based membranes should be measured in the presence of other components coexisting with H2 in the targeted real feed gases. For instance, in the typical H2 purification process, the presence of water vapor can give a major impact on the transport properties of H2 and CO2, since water vapor, which possesses a high polarizability and dipole moment (Table 1) , can preferentially interact with the functional groups on graphene surfaces. Secondly, graphene-membranes should be fabricated and tested in industrial module platforms, such as hollow fiber and spiral wound, the most popular configurations for gas separation applications. For example, as compared to flat films, the stacking of GO laminates can be changed in such membrane configurations, leading to different gas separation performances. To design the optimum GO membrane structure in such configurations and, eventually, achieve a high separation performance, aids from simulation and modeling studies are expected to be useful. Lastly, the stability and performance of graphene membranes should be tested under long-term operation conditions. In particular, the presence of water vapor or reactive components in the feed gas can alter the physical and chemical properties of graphene membranes. Thus, demonstrating a reliable performance over a long-term period is a prerequisite for graphene membranes to be promoted as a practical option in the gas separation market.

[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120][121][122][111][123][124][125][126][127][128][129][130][131][103]

References

- Ahmadpour, J.; Ahmadi, M.; Javdani, A. Hydrodesulfurization unit for natural gas condensate. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 135, 1943-1949.

- Kadijani, J.A.; Narimani, E. Simulation of hydrodesulfurization unit for natural gas condensate with high sulfur content. Appl. Petrochem. Res. 2016, 6, 25-34.

- Frauzem, R.; Kongpanna, P.; Roh, K.; Lee, J.H.; Pavarajarn, V.; Assabumrungrat, S.; Gani, R. Chapter 7 - Sustainable Process Design: Sustainable Process Networks for Carbon Dioxide Conversion. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, You, F., Ed. Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Vol. 36, pp. 175-195.

- Germeshuizen, L.M.; Blom, P. A techno-economic evaluation of the use of hydrogen in a steel production process, utilizing nuclear process heat. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2013, 38, 10671-10682.

- Grundt, T.; Christiansen, K. Hydrogen by water electrolysis as basis for small scale ammonia production. A comparison with hydrocarbon based technologies. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 1982, 7, 247-257.

- Yang, E.; Alayande, A.B.; Goh, K.; Kim, C.-M.; Chu, K.-H.; Hwang, M.-H.; Ahn, J.-H.; Chae, K.-J. 2D materials-based membranes for hydrogen purification: Current status and future prospects. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.04.053, doi:doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.04.053.

- Chuah, C.Y.; Goh, K.; Yang, Y.; Gong, H.; Li, W.; Karahan, H.E.; Guiver, M.D.; Wang, R.; Bae, T.-H. Harnessing filler materials for enhancing biogas separation membranes. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 8655-8769.

- Chuah, C.Y.; Kim, K.; Lee, J.; Koh, D.-Y.; Bae, T.-H. CO2 absorption using membrane contactors: recent progress and future perspective. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 59, 6773-6794.

- IEA. The Future of Hydrogen. Availabe online: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-hydrogen (accessed on June 6, 2020).

- Energy, O.o.E.E.R. Hydrogen Production: Natural Gas Reforming. Availabe online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-production-natural-gas-reforming (accessed on June 6, 2020).

- Vozniuk, O.; Tanchoux, N.; Millet, J.-M.; Albonetti, S.; Di Renzo, F.; Cavani, F. Chapter 14 - Spinel Mixed Oxides for Chemical-Loop Reforming: From Solid State to Potential Application. In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis, Albonetti, S., Perathoner, S., Quadrelli, E.A., Eds. Elsevier: 2019; Vol. 178, pp. 281-302.

- Navarro Yerga, R.M.; Alvarez-Galván, M.C.; Vaquero, F.; Arenales, J.; Fierro, J.L.G. Chapter 3 - Hydrogen Production from Water Splitting Using Photo-Semiconductor Catalysts. In Renewable Hydrogen Technologies, Gandía, L.M., Arzamendi, G., Diéguez, P.M., Eds. Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2013; pp. 43-61.

- Chuah, C.Y.; Goh, K.; Bae, T.-H. Hierarchically structured HKUST-1 nanocrystals for enhanced SF6 capture and recovery. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 6748-6755.

- Chuah, C.Y.; Yu, S.; Na, K.; Bae, T.-H. Enhanced SF6 recovery by hierarchically structured MFI zeolite. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 62, 64-71.

- Chuah, C.Y.; Yang, Y.; Bae, T.-H. Hierarchically porous polymers containing triphenylamine for enhanced SF6 separation. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2018, 272, 232-240.

- Yang, Y.; Goh, K.; Chuah, C.Y.; Karahan, H.E.; Birer, Ö.; Bae, T.-H. Sub-Ångström-level engineering of ultramicroporous carbons for enhanced sulfur hexafluoride capture. Carbon 2019, 155, 56-64.

- Tao, W.; Ma, S.; Xiao, J.; Bénard, P.; Chahine, R. Simulation and optimization for hydrogen purification performance of vacuum pressure swing adsorption. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 1917-1923.

- Xu, G.L., F.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, W. An Improved CO2 Separation and Purification System Based on Cryogenic Separation and Distillation Theory. Energies 2014, 7, 3484-3502.

- Wongchitphimon, S.; Lee, S.S.; Chuah, C.Y.; Wang, R.; Bae, T.H. Composite Materials for Carbon Capture; John Wiley & Sons: United States of America, 2020; pp. 237-266.

- Zhang, X.; Chuah, C.Y.; Dong, P.; Cha, Y.-H.; Bae, T.-H.; Song, M.-K. Hierarchically porous Co-MOF-74 hollow nanorods for enhanced dynamic CO2 separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 43316-43322.