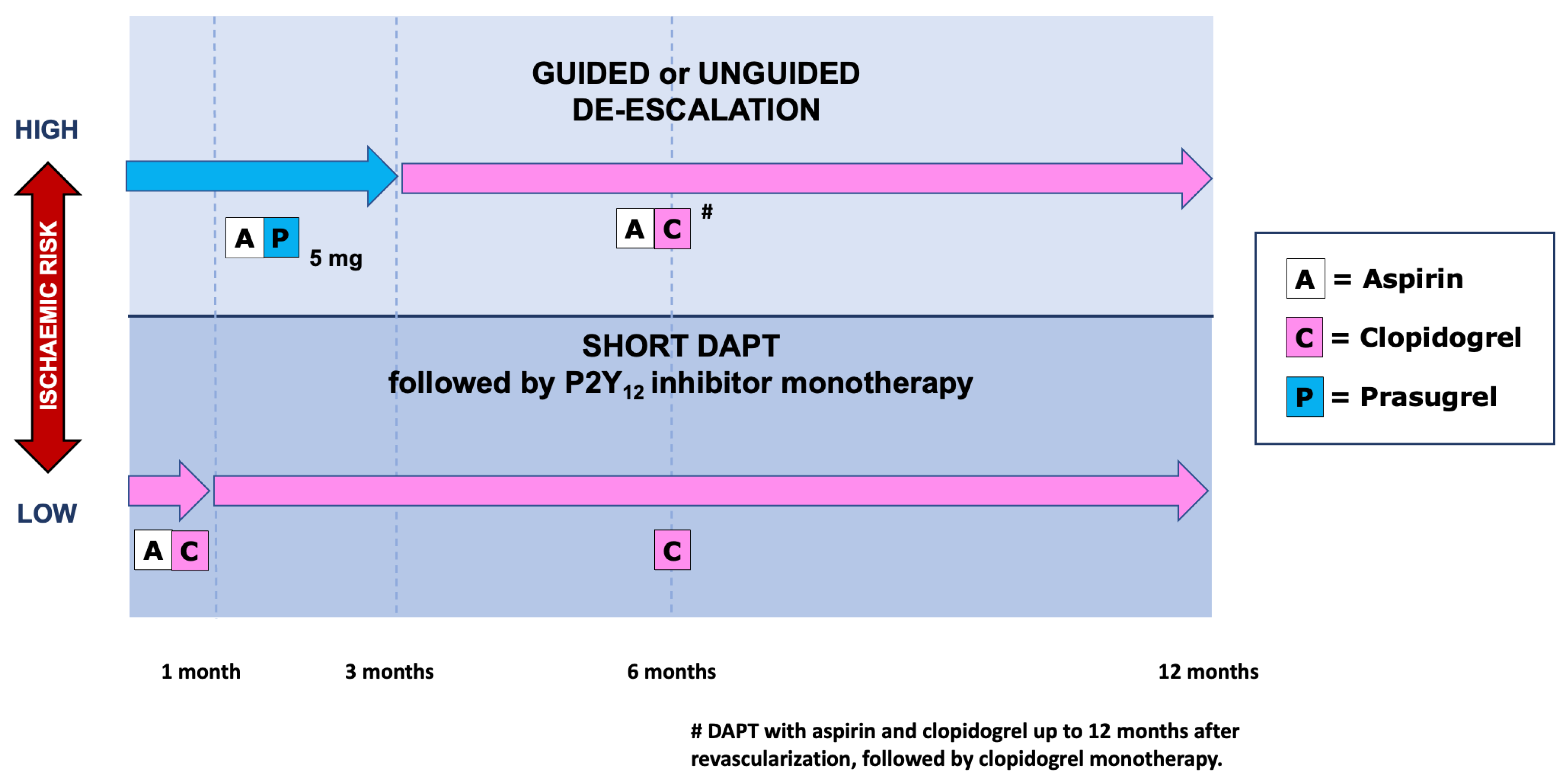

Patients ≥ 75 years of age account for about one third of hospitalizations for acute coronary syndromes (ACS). Since the European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend that older ACS patients use the same diagnostic and interventional strategies used by the younger ones, most elderly patients are currently treated invasively. Therefore, an appropriate dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is indicated as part of the secondary prevention strategy to be implemented in such patients. The choice of the composition and duration of DAPT should be tailored on an individual basis, after careful assessment of the thrombotic and bleeding risk of each patient. Advanced age is a main risk factor for bleeding. Recent data show that in patients of high bleeding risk short DAPT (1 to 3 months) is associated with decreased bleeding complications and similar thrombotic events, as compared to standard 12-month DAPT. Clopidogrel seems the preferable P2Y12 inhibitor, due to a better safety profile than ticagrelor. When the bleeding risk is associated with a high thrombotic risk (a circumstance present in about two thirds of older ACS patients) it is important to tailor the treatment by taking into account the fact that the thrombotic risk is high during the first months after the index event and then wanes gradually over time, whereas the bleeding risk remains constant.

- elderly patients

- acute coronary syndrome

- anti-platelet therapy

1. Introduction

2. Invasive versus Conservative Strategy

Although the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) STEMI guidelines state that “there is no upper age limit with respect to reperfusion, especially with primary PCI” [23][21], there is relatively little information regarding the outcomes of elderly patients undergoing primary PCI, due to the low representation of elderly patients in clinical trials assessing the effects of mechanical reperfusion for STEMI. A pooled analysis [24][22] including 834 patients enrolled in three randomized trials (Zwolle [25][23], SENIOR PAMI [26][24], and TRIANA [24][22]) showed that the overall risk of death, re-infarction, or disabling stroke was substantially lower for patients allocated to primary PCI compared with those treated with fibrinolysis (14.9% vs. 21.5%; odds ratio [OR], 0.64; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.45–0.91; p = 0.013), and s only a trend toward reduction of death was found (10.7% versus 13.8%, hazard ratio [HR] 0.74, 95% CI 0.49–1.13), although the effect size was superimposable to that of the largest metanalysis comparing fibrinolysis and primary PCI in younger patients. Septuagenarians and octogenarians undergoing primary PCI show higher mortality rates, both at short-term and mid-term follow-up than younger patients. In dedicated randomized trials in NSTE-ACS patients, the Italian Elderly ACS trial [13[13][25],31], which enrolled 313 patients with NSTE-ACS aged ≥75 years; the After Eighty trial [32][26], which randomized 557 patients with NSTE-ACS aged ≥80 years; and the RINCAL trial [33][27] that included 251 patients, the results went in the same direction: older patients allocated to the routine invasive strategy had a lower risk of death and MI, as shown by a meta-analysis (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.51–0.83; p < 0.001) at a median follow-up of 36 months. This result was mostly driven by a statistically significant reduction in MI with a trend towards a lower mortality rate, without heterogeneity among the studies [34][28]. A significant reduction in mortality was, however, found in the observational SENIOR NSTEMI cohort study that included patients aged >80 years: applying a propensity-score model, thise study showed that at 5 years the adjusted risk of dying was 44% lower with early invasive treatment, with the difference emerging from 1 year onwards [35][29]. The ongoing SENIOR-RITA trial is randomizing a large series of NSTEMI patients aged ≥75 years to determine the impact of a routine invasive strategy on cardiovascular death and non-fatal MI, compared with a conservative treatment strategy [36][30].3. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Elderly ACS Patients: Comparative Efficacy and Safety among Different P2Y12 Inhibitors

Data on optimal platelet inhibition in older adults is limited [41][31], because elderly patients were underrepresented in the pivotal trials: they accounted for only 13% of patients in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel—Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction study) [42][32] and for 15% in the PLATO (The Study of Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial [43][33]. Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with prasugrel at 10 mg daily dose associated with aspirin significantly increased bleeding in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial as compared to DAPT with clopidogrel [42][32], so that its use in elderly patients was not recommended by the Food and Drug Administration, whereas the European Medicines Agency indicated a 5 mg/day maintenance dose [44][34]. On the contrary, an analysis of the PLATO trial showed that the superiority of DAPT with ticagrelor over DAPT with clopidogrel (including a reduction in cardiovascular mortality) was confirmed also in the elderly population [45][35]. These indications were issued despite the fact that the differences in the primary endpoint of death, MI and stroke between clopidogrel and prasugrel in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial (18.3% vs. 17.2%) [42][32] and those between clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the PLATO trial (18.3% vs. 17.2%) [45][35] were exactly the same. Specific trials have been conducted in older ACS patients, comparing different P2Y12 inhibitors in association with aspirin. The ELDERLY ACS 2 trial randomized 1443 ACS patients aged ≥75 years who underwent PCI and showed similar combined thrombotic and bleeding events in patients assigned to 12-month DAPT with a prasugrel 5 mg maintenance dose and in those assigned to 12-month DAPT with clopidogrel 75mg [49][36]. In a post hoc analysis, DAPT with prasugrel 5 mg, as compared to DAPT with clopidogrel, reduced thrombotic events in the first month after the index event, but increased late bleeding (31–365 days) [50][37]. DAPT with low-dose prasugrel and clopidogrel also had similar efficacy and safety in medically treated elderly patients enrolled in the TRILOGY ACS (Targeted Platelet Inhibition to Clarify the Optimal Strategy to Medically Manage Acute Coronary Syndromes) study [51][38]. At odds with the results of the post hoc analysis of the PLATO trial, the POPular AGE (Ticagrelor or Prasugrel Versus Clopidogrel in Elderly Patients With an Acute Coronary Syndrome and a High Bleeding Risk: Optimization of Antiplatelet Treatment in High-Risk Elderly) trial showed that DAPT with clopidogrel had significantly lower bleeding rates (including fatal bleeding) compared with DAPT with ticagrelor (17.6% vs. 23.1%; OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.56–0.97), without any difference in thrombotic events (12.8% vs. 12.5%; OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.72–1.45) [53][39]. Notably, ticagrelor was prematurely discontinued in about half of the patients randomly allocated to that drug, a finding that could have hampered its potential benefits, but that also indicates that side effects induced by that drug affect a large part of older adults.4. Bleeding and Thrombotic Risk in Elderly ACS Patients

The goal of the antiplatelet therapy after ACS is to reduce the risk of recurrence of ischemic events, likewise attenuating the bleeding risk [60][40]. The choice of the composition and optimal duration of DAPT [61,62][41][42] should be made on an individual basis, and its effects repeatedly verified throughout the follow-up period. Therefore, cardiologists should assess the thrombotic and bleeding risk of each patient by considering clinical, anatomical, procedural and laboratory data. To this purpose, risk scores, especially for the measurement of the bleeding risk such as the PRECISE DAPT score [63][43] and the Academic Research Consortium High Bleeding Risk (ARC-HBR) criteria [64,65][44][45], may be helpful, and are recommended by guidelines [66][46]. Although almost all elderly patients satisfy the criteria for the definition of HBR, high thrombotic risk is also concomitant in many patients. This issue is well outlined in the ARC-HBR trade-off model proposed by Urban et al., who reported the results of 1-year clinical outcome of 6641 patients (26% with STEMI or NSTEMI) who underwent PCI with stent implantation and were categorized as HBR according to ARC criteria [71][47]. Prior MI, the presence of diabetes, STEMI presentation and bare-metal-stent implantation were predictors of MI and stent thrombosis in this HBR population. At the 1-year follow-up, slightly less than half of the patients (44.1%) had a greater risk of thrombotic events than major bleeding, and one third of patients faced a comparable risk of either type of adverse events. Of the 1.445 patients included in the ELDERLY-ACS 2 trial, more than two thirds (68%) had prior MI, diabetes or STEMI presentation, thus carrying a high thrombotic risk according to the ARC-HBR trade-off model [72][48]. These data show how HBR and high thrombotic risk coexist in a large number of elderly patients with ACS.5. Antiplatelet Strategies in Elderly ACS Patients

In a recent review on antiplatelet therapy in ACS [73][49], scholars propose different DAPT strategies according to the presence or absence of HBR and high thrombotic risk. As discussed above, in elderly patients only two conditions are to be considered: (1) isolated HBR, and (2) HBR associated with high thrombotic risk. For patients with isolated HBR, short DAPT is likely to be the best strategy. In the MASTER DAPT trial [74][50] that selectively randomized HBR patients (69% aged ≥75 years, 48% with ACS) to 1-month DAPT versus standard DAPT (median 157 days) followed by single antiplatelet agent (mostly clopidogrel in both groups), the abbreviated DAPT strategy was non-inferior to standard therapy for net adverse clinical events (NACE) and for ischemic events, but significantly reduced for major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding. This trial, however, also included patients taking anticoagulants (39%), for whom guidelines recommend an early DAPT cessation (1 week). The 1-month DAPT trial showed similar data [75][51]; that is, non-inferiority of short DAPT versus standard (6- to 12-month) DAPT followed by aspirin monotherapy for the 1-year composite of cardiovascular events or major bleeding in patients undergoing PCI for non-complex lesions [75][51]. However, in that trial a significant interaction was observed between treatment strategy and clinical presentation: ACS patients randomized to 1-month DAPT, contrary to stable ones, showed a numerical increase in cardiovascular events with no difference in bleeding as compared to standard-DAPT patients. These data caution against very short (1-month) DAPT periods followed by aspirin monotherapy in ACS patients [76][52].

6. Conclusions

The combination and duration of antiplatelet therapy in elderly patients with ACS is still a challenging issue, since most of these patients have both high bleeding and a high thrombotic risk. The evidence so far accumulated in the few studies involving this population favours a cautious approach, avoiding the use of powerful antiplatelet drugs such as full-dose prasugrel or ticagrelor. The suggestions expressed above and summarized in Figure 1 are mostly speculative, based on post hoc analyses from dedicated studies or from studies performed in general ACS populations. Randomized trials addressing the effects of therapeutic schemes based on the individual risk of elderly patients are needed, to clarify this issue.References

- Di Lorenzo, E.; Sauro, R.; Varricchio, A.; Capasso, M.; Lanzillo, T.; Manganelli, F.; Carbone, G.; Lanni, F.; Pagliuca, M.R.; Stanco, G.; et al. Randomized comparison of everolimus-eluting stents and sirolimus-eluting stents in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction: RACES-MI trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 7, 849–856.

- De Luca, G.; Schaffer, A.; Wirianta, J.; Suryapranata, H. Comprehensive meta-analysis of radial vs femoral approach in primary angioplasty for STEMI. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 2070–2081.

- De Luca, G.; Suryapranata, H.; Stone, G.W.; Antoniucci, D.; Tcheng, J.E.; Neumann, F.-J.; Bonizzoni, E.; Topol, E.J.; Chiariello, M. Relationship between patient’s risk profile and benefits in mortality from adjunctive abciximab to mechanical revascularization for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, 685–686.

- Verdoia, M.; Schaffer, A.; Barbieri, L.; Cassetti, E.; Piccolo, R.; Galasso, G.; Marino, P.; Sinigaglia, F.; De Luca, G. Benefits from new ADP antagonists as compared with clopidogrel in patients with stable angina or acute coronary syndrome undergoing invasive management: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 63, 339–350.

- Costa, F.; Montalto, C.; Branca, M.; Hong, S.J.; Watanabe, H.; Franzone, A.; Vranckx, P.; Hahn, J.Y.; Gwon, H.C.; Feres, F.; et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy duration after percutaneous coronary intervention in high bleeding risk: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 250, ehac706.

- Nichols, M.; Townsend, N.; Scarborough, P.; Rayner, M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: Epidemiological update. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 3028–3034.

- Silverio, A.; Cancro, F.P.; Di Maio, M.; Bellino, M.; Esposito, L.; Centore, M.; Carrizzo, A.; Di Pietro, P.; Borrelli, A.; De Luca, G.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of adverse events after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2022, 54, 382–392.

- Verdoia, M.; Schaffer, A.; Barbieri, L.; Bellomo, G.; Marino, P.; Sinigaglia, F.; Suryapranata, H.; De Luca, G. Impact of age on mean platelet volume and its relationship with coronary artery disease: A single-centre cohort study. Exp. Gerontol. 2015, 62, 32–36.

- De Luca, G.; Verdoia, M.; Cassetti, E.; Schaffer, A.; Cavallino, C.; Bolzani, V.; Marino, P. High fibrinogen level is an independent predictor of presence and extent of coronary artery disease among Italian population. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2011, 31, 458–463.

- Verdoia, M.; Barbieri, L.; Di Giovine, G.; Marino, P.; Suryapranata, H.; De Luca, G. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio and the Extent of Coronary Artery Disease: Results from a Large Cohort Study. Angiology 2016, 67, 75–82.

- De Luca, L.; Marini, M.; Gonzini, L.; Boccanelli, A.; Casella, G.; Chiarella, F.; De Servi, S.; Di Chiara, A.; Di Pasquale, G.; Olivari, Z.; et al. Contemporary trends and age-specific sex differences in management and outcome for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e004202.

- Leonardi, S.; Montalto, C.; Carrara, G.; Casella, G.; Grosseto, D.; Galazzi, M.; Repetto, A.; Tua, L.; Portolan, M.; Ottani, F.; et al. Clinical governance of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2022, 11, 797–805.

- Savonitto, S.; Cavallini, C.; Petronio, A.S.; Murena, E.; Antonicelli, R.; Sacco, A.; Steffenino, G.; Bonechi, F.; Mossuti, E.; Manari, A.; et al. Early aggressive versus initially conservative treatment in elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012, 5, 906–916.

- Morici, N.; Savonitto, S.; Murena, E.; Antonicelli, R.; Piovaccari, G.; Tucci, D.; Tamburino, C.; Fontanelli, A.; Bolognese, L.; Menozzi, M.; et al. Causes of death in patients ≥75 years of age with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 112, 1–7.

- Morici, N.; De Servi, S.; De Luca, L.; Crimi, G.; Montalto, C.; De Rosa, R.; De Luca, G.; Rubboli, A.; Valgimigli, M.; Savonitto, S. Management of acute coronary syndromes in older adults. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 1542–1553.

- Ekerstad, N.; Swahn, E.; Janzon, M.; Alfredsson, J.; Löfmark, R.; Lindenberger, M.; Carlsson, P. Frailty is independently associated with short-term outcomes for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation 2011, 124, 2397–2404.

- Dodson, J.A.; Hochman, J.S.; Roe, M.T.; Chen, A.Y.; Chaudhry, S.I.; Katz, S.; Zhong, H.; Radford, M.J.; Udell, J.A.; Bagai, A.; et al. The association of frailty with in-hospital bleeding among older adults with acute myocardial infarction: Insights from the ACTION Registry. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 11, 2287–2296.

- Damluji, A.A.; Forman, D.E.; Wang, T.Y.; Chikwe, J.; Kunadian, V.; Rich, M.W.; Young, B.A.; Page, R.L., 2nd; DeVon, H.A.; Alexander, K.P.; et al. Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome in the Older Adult Population: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 147, e32–e62.

- De Luca, G.; Dirksen, M.T.; Spaulding, C.; Kelbæk, H.; Schalij, M.; Thuesen, L.; van der Hoeven, B.; Vink, M.A.; Kaiser, C.; Musto, C.; et al. Impact of diabetes on long-term outcome after primary angioplasty: Insights from the DESERT cooperation. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1020–1025.

- De Luca, G.; Verdoia, M.; Savonitto, S.; Piatti, L.; Grosseto, D.; Morici, N.; Bossi, I.; Sganzerla, P.; Tortorella, G.; Cacucci, M.; et al. Impact of diabetes on clinical outcome among elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with percutaneous coronary intervention: Insights from the ELDERLY ACS 2 trial. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 21, 453–459.

- Ibanez, B.; James, S.; Agewall, S.; Antunes, M.J.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Bueno, H.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Crea, F.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Halvorsen, S.; et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with STsegment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 119–177.

- Bueno, H.; Betriu, A.; Heras, M.; Alonso, J.J.; Cequier, A.; Garcia, E.J.; Lopez-Sendon, J.L.; Macaya, C.; Hernandez-Antolin, R.; Bueno, H.; et al. Primary angioplasty vs. fibrinolysis in very old patients with acute myocardial infarction: TRIANA (TRatamiento del Infarto Agudo de miocardio eN Ancianos) randomized trial and pooled analysis with previous studies. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 51–60.

- de Boer, M.J.; Ottervanger, J.P.; van’t Hof, A.W.J.; Hoornethe, A.; Suryapranata, H.; Zijlstra, F.; on behalf of the Zwolle Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Reperfusion therapy in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. A randomized comparison of primary angioplasty and thrombolytic therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39, 1723–1728.

- Grines, C. SENIOR PAMI: A prospective randomized trial of primary angioplasty and thrombolytic therapy in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. Presented at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics, Washington, DC, USA; 2005. Available online: https://www.acc.org (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Galasso, G.; De Servi, S.; Savonitto, S.; Strisciuglio, T.; Piccolo, R.; Morici, N.; Murena, E.; Cavallini, C.; Petronio, A.S.; Piscione, F. Effect of an invasive strategy on outcome in patients ≥75 years of age with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 115, 576–580.

- Tegn, N.; Abdelnoor, M.; Aaberge, L.; Endresen, K.; Smith, P.; Aakhus, S.; Gjertsen, E.; Dahl-Hofseth, O.; Ranhoff, A.H.; Gullestad, L.; et al. Invasive versus conservative strategy in patients aged 80 years or older with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris (After Eighty study): An open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1057–1065.

- de Belder, A.; Myat, A.; Blaxill, J.; Haworth, P.; O’Kane, P.; Hatrick, R.; Aggarwal, R.K.; Davie, A.; Smith, W.; Gerber, R.; et al. Revascularisation or medical therapy in elderly patients with acute anginal syndromes: The RINCAL randomised trial. EuroIntervention 2021, 17, 67–74.

- Garg, A.; Garg, L.; Agarwal, M.; Rout, A.; Raheja, H.; Agrawal, S.; Rao, S.V.; Cohen, M. Routine invasive versus selective invasive strategy in elderly patients older than 75 years with Non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 436–444.

- Kaura, A.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Trickey, A.; Abbott, S.; Mulla, A.; Glampson, B.; Panoulas, V.; Davies, J.; Woods, K.; Mayet, J.; et al. Invasive versus non-invasive management of older patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (SENIOR-NSTEMI): A cohort study based on routine clinical data. Lancet 2020, 396, 623–634.

- The British Heart Foundation SENIOR-RITA Trial (SENIOR-RITA). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03052036 (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Verdoia, M.; Pergolini, P.; Rolla, R.; Nardin, M.; Schaffer, A.; Barbieri, L.; Marino, P.; Bellomo, G.; Suryapranata, H.; De Luca, G. Advanced age and high-residual platelet reactivity in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel or ticagrelor. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2016, 14, 57–64.

- Wiviott, S.D.; Braunwald, E.; McCabe, C.H.; Montalescot, G.; Ruzyllo, W.; Gottlieb, S.; Neumann, F.J.; Ardissino, D.; De Servi, S.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2001–2015.

- Wallentin, L.; Becker, R.C.; Budaj, A.; Cannon, C.P.; Emanuelsson, H.; Held, C.; Horrow, J.; Husted, S.; James, S.; Katus, H.; et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1045–1057.

- De Servi, S.; Goedicke, J.; Schirmer, A.; Widimsky, P. Clinical outcomes for prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: An analysis from the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2014, 4, 363–372.

- Husted, S.; James, S.; Becker, R.C.; Horrow, J.; Katus, H.; Storey, R.F.; Cannon, C.P.; Heras, M.; Lopes, R.D.; Morais, J.; et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes: A substudy from the prospective randomized PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2012, 5, 680–688.

- Savonitto, S.; Ferri, L.A.; Piatti, L.; Grosseto, D.; Piovaccari, G.; Morici, N.; Bossi, I.; Sganzerla, P.; Tortorella, G.; Cacucci, M.; et al. Comparison of reduced-dose prasugrel and standard-dose clopidogrel in elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing early percutaneous revascularization. Circulation 2018, 137, 2435–2445.

- Crimi, G.; Morici, N.; Ferrario, M.; Ferri, L.A.; Piatti, L.; Grosseto, D.; Cacucci, M.; Mandurino Mirizzi, A.; Toso, A.; Piscione, F.; et al. Time course of ischemic and bleeding burden in elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes randomized to low-dose prasugrel or clopidogrel. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e010956.

- Roe, M.T.; Goodman, S.G.; Ohman, E.M.; Stevens, S.R.; Hochman, J.S.; Gottlieb, S.; Martinez, F.; Dalby, A.J.; Boden, W.E.; White, H.D.; et al. Elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes managed without revascularization: Insights into the safety of long-term dual antiplatelet therapy with reduced-dose prasugrel versus standard-dose clopidogrel. Circulation 2013, 128, 823–833.

- Gimbel, M.; Qaderdan, K.; Willemsen, L.; Hermanides, R.; Bergmeijer, T.; de Vrey, E.; Heestermans, T.; Tjon Joe Gin, M.; Waalewijn, R.; Hofma, S.; et al. Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-STelevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): The randomised, open label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1374–1381.

- Valgimigli, M.; Bueno, H.; Byrne, R.A.; Collet, J.P.; Costa, F.; Jeppsson, A.; Jüni, P.; Kastrati, A.; Kolh, P.; Mauri, L.; et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: The Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 213–260.

- De Luca, G.; Damen, S.A.; Camaro, C.; Benit, E.; Verdoia, M.; Rasoul, S.; Liew, H.B.; Polad, J.; Ahmad, W.A.; Zambahari, R.; et al. Final results of the randomised evaluation of short-term dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with a new-generation stent (REDUCE trial). EuroIntervention 2019, 15, e990–e998.

- Kedhi, E.; Verdoia, M.; Suryapranata, H.; Damen, S.; Camaro, C.; Benit, E.; Barbieri, L.; Rasoul, S.; Liew, H.B.; Polad, J.; et al. Impact of age on the comparison between short-term vs 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with the COMBO dual therapy stent: 2-Year follow-up results of the REDUCE trial. Atherosclerosis 2021, 321, 39–44.

- Costa, F.; van Klaveren, D.; James, S.; Heg, D.; Räber, L.; Feres, F.; Pilgrim, T.; Hong, M.K.; Kim, H.S.; Colombo, A.; et al. Derivation and validation of the predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy (PRECISE-DAPT) score: A pooled analysis of individual-patient datasets from clinical trials. Lancet 2017, 389, 1025–1034.

- Urban, P.; Mehran, R.; Colleran, R.; Angiolillo, D.J.; Byrne, R.A.; Capodanno, D.; Cuisset, T.; Cutlip, D.; Eerdmans, P.; Eikelboom, J.; et al. Defining high bleeding risk in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A consensus document from the Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 2632–2653.

- Fortuni, F.; Crimi, G.; Morici, N.; De Luca, G.; Alberti, L.P.; Savonitto, S.; De Servi, S. Assessing bleeding risk in acute coronary syndrome using the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium definition. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 20, 818–824.

- Gragnano, F.; Heg, D.; Franzone, A.; McFadden, E.P.; Leonardi, S.; Piccolo, R.; Vranckx, P.; Branca, M.; Serruys, P.W.; Benit, E.; et al. PRECISE-DAPT score for bleeding risk prediction in patients on dual or single antiplatelet regimens: Insights from the GLOBAL LEADERS/and GLASSY. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2022, 8, 28–38.

- Urban, P.; Gregson, J.; Owen, R.; Mehran, R.; Windecker, S.; Valgimigli, M.; Varenne, O.; Krucoff, M.; Saito, S.; Baber, U.; et al. Assessing the risks of bleeding vs thrombotic events in patients at high bleeding risk after coronary stent implantation: The ARC–High Bleeding Risk Trade-off Model. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 410–419.

- Morici, N.; Savonitto, S.; Ferri, L.A.; Grosseto, D.; Bossi, I.; Sganzerla, P.; Tortorella, G.; Cacucci, M.; Ferrario, M.; Crimi, G.; et al. Outcomes of Elderly Patients with ST-Elevation or Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 209–216.

- De Servi, S.; Landi, A.; Savonitto, S.; De Luca, L.; De Luca, G.; Morici, N.; Montalto, C.; Crimi, G.; Cattaneo, M. Tailoring oral antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes: From guidelines to clinical practice. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24, 77–86.

- Valgimigli, M.; Frigoli, E.; Heg, D.; Tijssen, J.; Jüni, P.; Vranckx, P.; Ozaki, Y.; Morice, M.C.; Chevalier, B.; Onuma, Y.; et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy after PCI in patients at high bleeding risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1643–1655.

- Hong, S.J.; Kim, J.S.; Hong, S.J.; Lim, D.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Yun, K.H.; Park, J.K.; Kang, W.C.; Kim, Y.H.; Yoon, H.J.; et al. 1-Month dual-antiplatelet therapy followed by aspirin monotherapy after polymer-free drug-coated stent implantation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 1801–1811.

- Capranzano, P. One-month DAPT after acute coronary syndrome: Too short or not too short? EuroIntervention 2022, 18, 443–445.

- De Luca, L.; De Servi, S.; Musumeci, G.; Bolognese, L. Is ticagrelor safe in octogenarian patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes? Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2018, 4, 12–14.

- Montalto, C.; Morici, N.; Munafò, A.R.; Mangieri, A.; Mandurino-Mirizzi, A.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Oreglia, J.; Latib, A.; Porto, I.; Colombo, A.; et al. Optimal P2Y12 inhibition in older adults with acute coronary syndromes: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2022, 8, 20–27.

- Llaó, I.; Ariza-Solé, A.; Sanchis, J.; Alegre, O.; López-Palop, R.; Formiga, F.; Marín, F.; Vidán, M.T.; Martínez-Sellés, M.; Sionis, A.; et al. Invasive strategy and frailty in very elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes. EuroIntervention 2018, 14, e336–e342.

- Andò, G.; De Santis, G.A.; Greco, A.; Pistelli, L.; Francaviglia, B.; Capodanno, D.; De Caterina, R.; Capranzano, P. P2Y12 Inhibitor or Aspirin Following Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Network Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 2239–2249.

- Lin, K.J.; De Caterina, R.; Rodriguez, L.A.G. Low-dose aspirin and upper gastrointestinal bleeding in primary versus secondary cardiovascular prevention: A population-based, nested case-control study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2014, 7, 70–77.

- Sundstrom, J.; Hedberg, J.; Thuresson, M.; Aarskog, P.; Johannesen, K.M.; Oldgren, J. Low-Dose Aspirin Discontinuation and Risk of Cardiovascular Events: A Swedish Nationwide, Population-Based Cohort Study. Circulation 2017, 136, 1183–1192.

- Koo, B.K.; Kang, J.; Park, K.W.; Rhee, T.M.; Yang, H.M.; Won, K.B.; Rha, S.W.; Bae, J.W.; Lee, N.H.; Hur, S.H.; et al. Aspirin versus clopidogrel for chronic maintenance monotherapy after percutaneous coronary intervention (HOST-EXAM): An investigator-initiated, prospective, randomized, open-label, multicenter trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 2487–2496.

- Kang, J.; Park, K.W.; Lee, H.; Hwang, D.; Yang, H.M.; Rha, S.W.; Bae, J.W.; Lee, N.H.; Hur, S.H.; Han, J.K.; et al. Aspirin vs. Clopidogrel for Chronic Maintenance Monotherapy after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The HOST-EXAM Extended Study. Circulation 2023, 147, 108–117.

- Nelson, T.A.; Parker, W.A.E.; Ghukasyan Lakic, T.; Westerbergh, J.; James, S.K.; Siegbahn, A.; Becker, R.C.; Himmelmann, A.; Wallentin, L.; Storey, R.F. Differential effect of clopidogrel and ticagrelor on leukocyte count in relation to patient characteristics, biomarkers and genotype: A PLATO substudy. Platelets 2022, 33, 425–431.

- Palmerini, T.; Barozzi, C.; Tomasi, L.; Sangiorgi, D.; Marzocchi, A.; De Servi, S.; Ortolani, P.; Reggiani, L.B.; Alessi, L.; Lauria, G.; et al. A randomised study comparing the antiplatelet and antinflammatory effect of clopidogrel 150 mg/day versus 75 mg/day in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction and poor responsiveness to clopidogrel: Results from the DOUBLE study. Thromb. Res. 2010, 125, 309–314.

- Ferrucci, L.; Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: Chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 505–522.

- Laudani, C.; Greco, A.; Occhipinti, G.; Ingala, S.; Calderone, D.; Scalia, L.; Agnello, F.; Legnazzi, M.; Mauro, M.S.; Rochira, C.; et al. Short duration of DAPT versus de-escalation after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 268–277.

- Montalto, C.; Crimi, G.; Morici, N.; Savonitto, S.; De Servi, S. Use of clinical risk score in an elderly population: Need for ad hoc validation and calibration. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 161–162.