Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Phetole Mangena and Version 2 by Lindsay Dong.

Polyploidy induction is recognized as one of the major evolutionary processes leading to remarkable morphological, physiological, and genetic variations in plants. Soybean (Glycine max L.), also known as soja bean or soya bean, is an annual leguminous crop of the pea family (Fabaceae) that shares a paleopolypoidy history, dating back to approximately 56.5 million years ago with other leguminous crops such as cowpea and other Glycine specific polyploids.

- :biochemical traits

- colchicine

- salinity stress

- soybean

1. Introduction

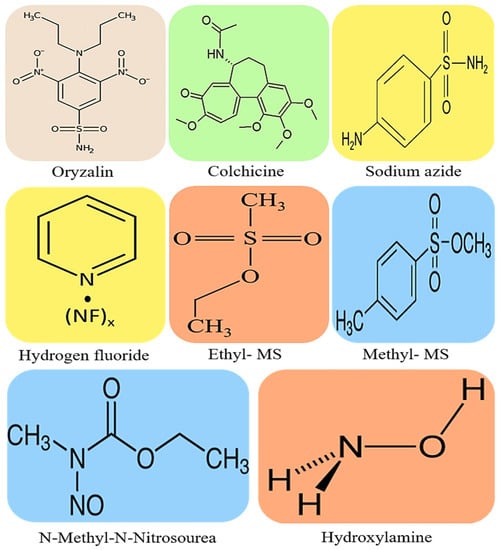

Polyploidy induction is recognized as one of the major evolutionary processes that leads to a variety of remarkable morphological, physiological, and genetic variations in plants [1][2][3][1,2,3]. In Fabaceous crops such as soybean, also known as soja bean or soya bean, Kim et al. [1] reported a paleopolypoidy history that dates back to approximately 56.5 million years ago, which is similar to that of common bean and other Glycine specific polyploids. This history of evolution and diversification of plant species also drove soybean domestication and the improvement of its agronomic as well as nutritional characteristics [4]. Both soybean’s evolutionary path and domestication led this crop to become one of the current major sources of dietary carbohydrates, fibre, minerals, oil, proteins and vitamins for human and animal consumption [5]. Generally, plant polyploidization consists of the multiplication of a complete set of chromosomes that co-exist within a single cell nucleus. Progenies, subsequently leading to the formation of diversified species’ mutant varieties [6], can stably inherit these newly formed genomic features. In leguminous plants and likewise in non-leguminous species such as rice, wheat, tomato, cutleaf groundcherry etc., polyploidization has been widely tested using chemicals such as colchicine [7], epoxomicin [8], sodium azide [9], oryzalin [10], nitroxide [11] and ethyl methanesulfonate [12], some of which are illustrated below in Figure 1. These chemical compounds cause numerous genetic mutations that result in significant changes in the plant’s nuclear and proteome systems. Although the induced mutations can cause genetic defects and undesirable deformities that are easily identified through phenotypic evaluations, the changes incurred also serve as an alternative means of achieving genetic variations which contribute to the much-needed species diversity.

Figure 1. Chemical structure depictions of the most commonly used compounds for mutagenic crop improvement against biotic and abiotic stresses: oryzalin with a molecular weight (MW) of 346.36 g/mol, colchicine with a MW of 399.437 g/mol, sodium azide with a MW of 65.0099 g/mol, hydrogen fluoride with a MW of 20.0064 g/mol, ethyl methanesulfonate (Ethyl-MS) with a MW of 124.16 g/mol, methyl methanesulfonate (methyl-MS) with a MW of 110.13 g/mol, N-Methyl-N-Nitrosourea with a MW of 103.08 g/mol, and hydroxylamine with a MW of 33.03 mg/mol.

2. Genetic Architecture and Response to Salinity Stress in Soybean

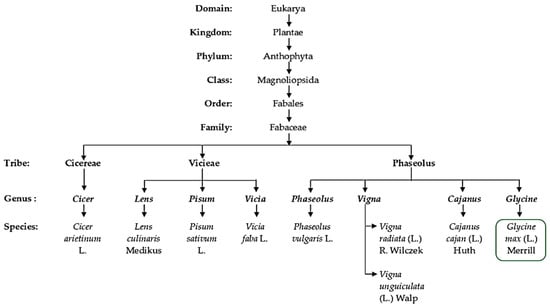

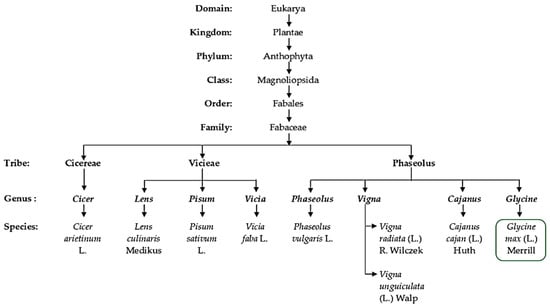

As a partial tetraploid, soybean is a legume belonging to the Fabales, which comprise more than 20,055 species, distributed within about 754 genera and making up nearly 10% of the eudicots [13][14][24,25]. Legumes experienced whole genome duplication after the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary (KPB) mass extension [14][25]. Especially, with allopolyploidy events giving rise to the ancestral species, Glycine soja is proposed to be a wild progenitor of Glycine max L. (soybean) [15][26]. Undoubtedly, species found within the Eurosid 1 angiosperm group constitute many of the most economically and agronomically important leguminous plants (Figure 2), in particular, species of the tribes Vicieae, Cicereae, Dalbergieae, Genisteae, Indigofereae and Phaseoleae [16][17][27,28]. Species from these selected families are used as food crops, directly or indirectly, in the form of ripe-mature or unripe-immature pods, as well as mature and immature dry seeds. Figure 2 shows the taxonomic classification of cultivated leguminous species used as grain and forage crops for human and animal consumption. Among them, soybean falls within the Phaseoleae tribe with prominent and widely domesticated species such as pigeon pea, dry bean, black gram, mung bean and cowpea. However, a species-comprehensive phylogenetic illustration (Figure 2) is important for capturing the full species diversity and taxa relationships for most cultivated grain legumes belonging to all natural tribes, especially the Vicieae and Phaseoleae. Both tribes consist of species exhibiting similar phylogenetic characters needed to overcome food insecurity and limitations such as inefficient nodulation, and resistance to biotic and abiotic stress constraints. Furthermore, the species within these tribes belong to a super clade called eudicot, which clearly demonstrates diversity in morphology, physiology, ecology and anatomical/structural support mechanisms in response to stresses such as drought and salinity [18][29]. Like many of these plants, soybean evolutionarily contains inherent morpho-physiological and biochemical mechanisms that permit it to thrive under high salt stress environments. Taxonomically similar to other species within the tribe, which is traditionally regarded as the clade of unnatural taxon (Figure 2), with mainly edible species [19][30], this crop exhibits growth features required to cope with significant levels of abiotic stress.

Figure 2. A summary of a taxonomic classification scheme highlighting the position of soybean (Glycine max L.) and other selected grain leguminous crops, as well as their botanical names (genus and species).

Among the complex and elegant strategies to overcome abiotic salt stress, soybeans convert stress signals to alter gene expression in order to activate mechanisms of acclimation and tolerance. The first salt stress-sensing mechanism triggers a downstream response comprising multiple signal transduction pathways. These pathways involve activation of transcriptional regulators, ROS signaling and accumulation of secondary metabolites such as hormones, among others [20][22]. This signaling, in turn, regulates metabolic and gene expression reprogramming that bring about cellular stability under salinity conditions.

3. Improvement of Salt Stress Tolerance via Polyploidy Induction in Plants

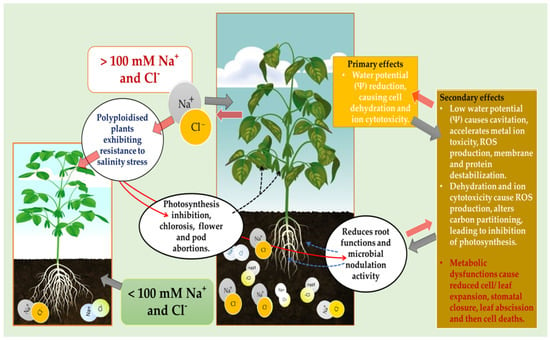

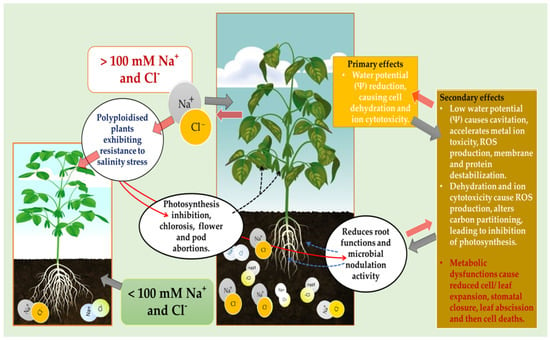

The yield of soybean is significantly decreased by salinity stress, especially by the negative influence on the vegetative growth stages of this crop, as represented in Figure 3. Salinity is predicted to affect at least 50% of cultivated land worldwide by the year 2050 [21][32]. This stress causes primary negative effects by reducing cell water potential, causing dehydration and ion cytotoxicity, and secondary effects leading to ROS production, membrane destabilization, protein degradation and inhibition of photosynthesis (Figure 2). As previously emphasized, salinity inhibits growth and development of the whole plant by causing ROS accumulation, and water and ionic imbalances in plant cells [21][22][23][21,32,33]. The Foyer–Halliwell–Asada pathway, also known as the glutathione-ascorbate cycle, that detoxifies ROS is one major mechanism used by the genetically enhanced polyploids to tolerate and survive salinity stress [24][34]. The ascorbate–glutathione or glutathione–ascorbate cycle eliminates ROS through the activity of ascorbate peroxidase, monodehydroascorbate reductase, dehydroascorbate reductase and glutathione reductase. These enzymes play a vital role in detoxifying ROS effects, as indicated in Figure 3, especially during abiotic stress where the harmful oxygen free radical production is increasing, even surpassing the antioxidant defense capacity of diploid plants compared with the polyploidised ones [24][25][34,35].

Figure 3.

Potential effects of salinity on the growth and development of polyploidized and diploid soybean plants.

Apart from ROS detoxification, plants also use compartmentalization or exportation of ions to different internal/external structures to achieve suitable osmotic adjustments. In this way, plants are generally able to regulate Na+/Cl− ion uptake and carry out long-distance transport and intracellular compartmentalization in the vacuole and other specialized tissues to avoid excessive salt accumulation and cell damage by Na+/Cl− influx [26][36].

3.1. Vegetative Growth Characteristics for Salinity Tolerance

Induced polyploidization as a tool for improving crop traits was discovered in 1907, and was thought to be responsible for heritability in genomic characteristics [2]. It was then later demonstrated that different ploidy levels caused different effects on the morphology and physiology of plants. As reported earlier by Alam et al. [27][38], tetraploid and triploid Camellia sinensis mutant plants showed more vigour and leaf hardness due to increased sizes of cortical and mesophyll cells, which increased eight-fold compared with six-fold in diploid cells. However, evidence of the effects of synthetic polyploidy application in legumes, particularly, in soybean is very limited. A few detailed and insightful scholarly works that are available about polyploidy at all levels clearly show that this phenomenon induces changes in plant phenotypes via the altered genome, also influencing interactions with abiotic and biotic environmental stress factors [28][39]. Forrester and Ashman [28][39] reported that polyploidy directly increased the quantity and quality of rhizobia symbionts found in legumes such as Glycine wightii, Medicago sativa, Stylosanthes hamata and several Trifolium spp., resulting in enhanced nitrogen (N) fixation due to larger quantities of nodules (8.8 to 119.8), improved nodule sizes (up to 3.0 mm) and higher root density (0.21 cm−2cm−3 to 1.38 cm−2cm−3). In cowpea, attempts have been made using this tool to improve primitive and long-existing characteristics such as small seed size, hairiness, and exined pollen grain surfaces [29][40].