Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 1 by Dan Yin.

Myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (I/R) are the most common heart diseases, yet there is currently no effective therapy due to their complex pathogenesis. Cardiomyocytes (CMs), fibroblasts (FBs), endothelial cells (ECs), and immune cells are the primary cell types involved in heart disorders, and, thus, targeting a specific cell type for the treatment of heart disease may be more effective. The same interleukin may have various effects on different kinds of cell types in heart disease. CMs are the beating muscle cells that make up the atria and ventricles and are being targeted primarily in heart disease therapy.

- heart disease

- interleukin

- cardiomyocytes

1. Introduction

Heart disease is the leading cause of death worldwide [1]. Heart disease generally includes myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (I/R) [2]. There are no effective therapy methods currently because of their complex pathogenesis. Heart disease is characterized by the involvement of four major cell types: cardiomyocytes (CMs), fibroblasts (FBs), endothelial cells (ECs), and immune cells [3]. CMs, FBs, and ECs are resident cells in the heart; however, immune cells are infiltrated during inflammation, and they play a significant role in the pathophysiological process of heart disease. Thus, targeting a specific cell type for the treatment of heart disease may be more effective.

Inflammation has been identified as a potential initiator and promoter of heart disease. Different interleukin (IL) families have been linked to the development of heart disease, either positively or negatively. Proinflammatory factors such as IL-1β antagonists or antibodies have shown promising results in early clinical trials for heart disease [2]. Despite this, researchers are still exploring more effective cytokine treatment methods. However, the same interleukin may have various effects on different cell types of the heart. For instance, IL-11 has been found to mediate cytoprotective signals in cardiomyocytes [4], yet it has also been reported to have a profibrotic effect in cardiac fibrosis [5].

The IL-1 family is a major cytokine family associated with various cardiovascular diseases, initially comprising only two forms, IL-1α and IL-1β. To date, the IL-1 family has expanded to include 11 members (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-18, IL-33, IL-36Ra, IL-36α, IL-36β, IL-36γ, IL-37, and IL-38), with most of them being proinflammatory, while IL-1ra, IL-36Ra, IL-37, and IL-38 are anti-inflammatory [6].

IL-2 is an O-glycosylated four alpha-helix bundle cytokine that is primarily produced by activated T cells, dendritic cells, and B cells. It plays a pivotal role in the immune response to heart disease by regulating B-cell proliferation and immunoglobulin production, as well as maintaining T-cell homeostasis [7].

IL-4 is a glycosylated, type I cytokine with three intrachain disulfide bridges. It is mainly produced by T cells, natural killer T cells, mast cells, and eosinophils. In addition, it plays a central dual role in the development of inflammation in heart disease [8].

IL-6 is the founding member of the IL-6 cytokine family, which also includes IL-11, IL-27, IL-30, IL-31, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), oncostatin M (OSM), cardiotrophin-like cytokine (CLC), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), cardiotrophin-1 (CT-1), and neuropoietin. It is produced by numerous different cell types and is essential for regulating heart disease progression. IL-6-IL-6 R alpha complex promotes gp130 dimerization and the formation of a heterohexameric complex [9].

The CXCL8 gene encodes interleukin-8 (IL-8), a key mediator with both deleterious and beneficial properties. Multiple studies have reported elevated levels of IL-8 in various cardiac pathologies, including MI, suggesting that IL-8 could be a potential therapeutic target for heart disease [10].

The IL-10 family is composed of six members, namely IL-10, IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-24, and IL-26. As the founding member, IL-10 has anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties that serve to prevent excessive inflammation. It has been demonstrated to inhibit the antigen presentation capabilities of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, while simultaneously enhancing their tolerance-inducing, scavenger, and phagocytic functions. Additionally, IL-10 has been shown to suppress Th1-, Th2-, and Th17-mediated immune responses by inhibiting the proliferation of CD4+ T cells and their ability to produce proinflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, it has been observed to inhibit the secretion of proinflammatory mediators by neutrophils, eosinophils, and mast cells, as well as mast cell development.

IL-17 has been demonstrated to exert a wide range of biological activities on a variety of cell types, including CMs, ECs, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages. This cytokine has been shown to be involved in the inflammatory response in heart disease, suggesting a potential role in the pathogenesis of this condition [11].

2. Effects of Interleukins on Cardiomyocytes (CMs) in Heart Disease

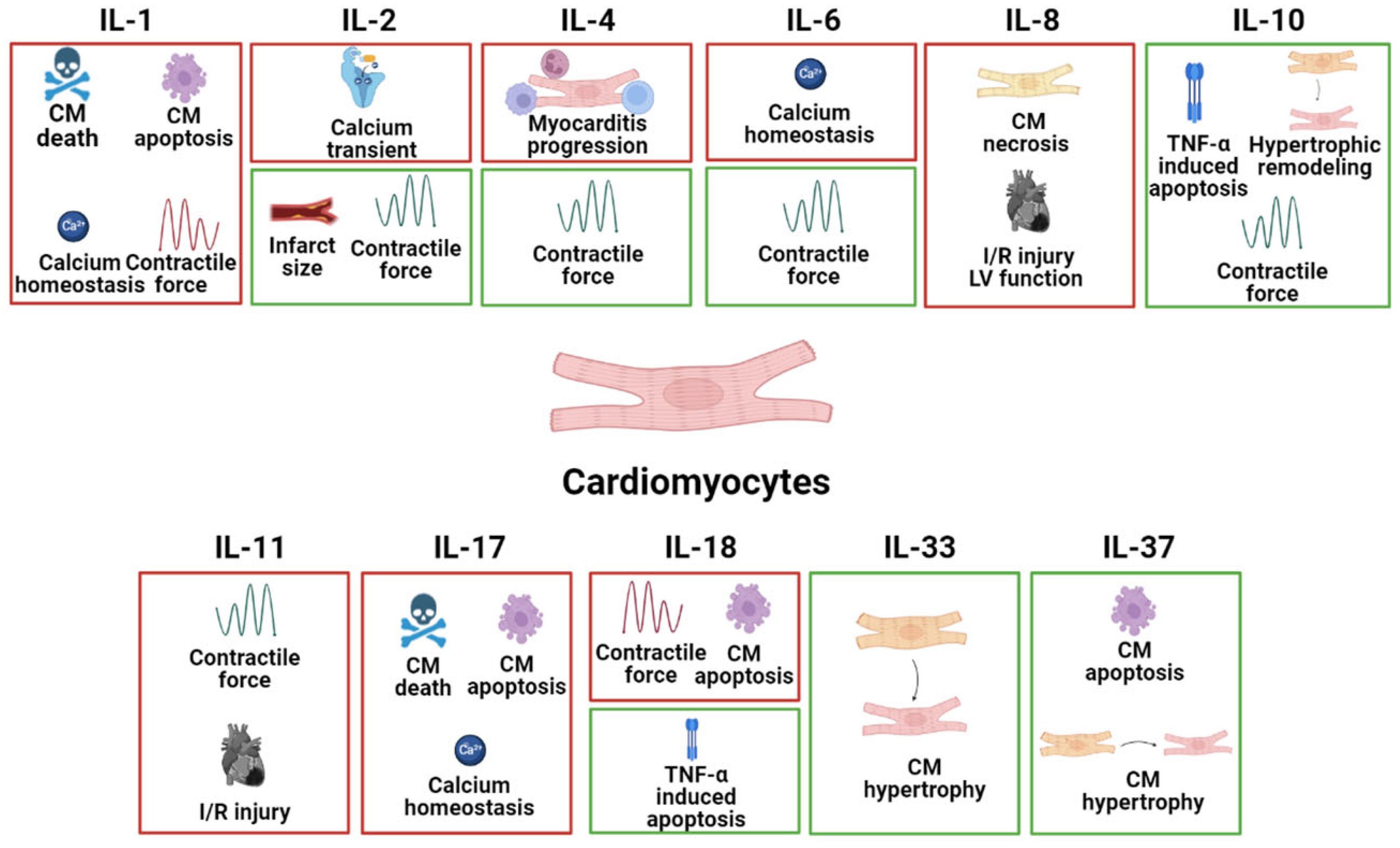

CMs are the beating muscle cells that make up the atria and ventricles and are being targeted primarily in heart disease therapy. The specific effects of different interleukins on CMs in common heart disease are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The specific pathophysiological effects of different interleukins on CMs in common heart disease. The box in red represents the deleterious role, and the box in green represents the protective role.

2.1. IL-1

IL-1α and IL-1β are proinflammatory cytokines and their levels are correlated with the severity and pathogenesis of heart disease. Targeting the IL-1 signaling cascade including IL-1α and IL-1β may be a promising therapeutic target for patients with MI [12,13][12][13]. Moreover, in vivo MI mouse models have shown that inhibition of IL-1α reduces myocardial I/R damage, resulting in the retention of left ventricular function, reduced infarction area, and decreased activation of inflammatory bodies [14]. Thus, IL-1α blockers may represent an effective therapeutic approach to reduce I/R damage to the heart. In a mouse model of MI, dead cardiomyocytes will release IL-1α [15,16][15][16]. In addition, the release of IL-1β in fulminant myocarditis leads to extensive inflammation, leading to the further death of cardiomyocytes, the gradual loss of active contracted tissue, and the development of cardiomyopathy and HF. IL-1β is concentration-dependent and may elevate myocardial ring GMP through the myocardial L-arginine-NO pathway, leading to the restriction of systolic ejection and cardiac depression [13]. The regulation of the excitatory-contractile coupling of cardiomyocytes is reflected in changes in contractile force, and cytokine-specific effects appear to exist in the excitatory–contraction coupling, with TNF-α and IL-1β affecting inward calcium currents [17,18][17][18]. IL-1β has been shown to significantly prolong the duration of the action potential of guinea pig ventricular cells by changing the conductance of calcium channels [19]. IL-1β has been shown to rapidly inhibit the voltage-dependent Ca2+ current in adult rat ventricular muscle cells. Consistent with these data, IL-1β has been shown to inhibit systolic cardiomyocyte function by potentially involving the destruction of calcium processing or the inhibition of a β-adrenergic response [20,21][20][21]. In patients with HF, IL-1β has been demonstrated to decrease the beta-adrenergic responsiveness of L-type calcium channels, as well as decrease calcium homeostasis genes, including phospholamban and sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase [22,23][22][23]. Furthermore, IL-1β has been shown to have a proapoptotic effect on cardiomyocytes [24] and exert negative inspiratory effects on both isolated cardiomyocytes and intact hearts [13,25][13][25].2.2. IL-2

Recent studies have demonstrated that high doses of IL-2 may induce AMI [26]. In isolated normal myocytes, IL-2 was found to decrease the amplitude of calcium transients induced by electrical stimulation, likely through blocking Ca2+ ATPase activity in the sarcoplasmic reticulum [27]. Furthermore, IL-2 concentrations produced by CD4+ T lymphocytes were abnormally elevated in patients with DCM, which may reflect deficiencies in T-cell function in these patients [28]. However, there are also studies demonstrating the protective role of IL-2 in MI. The injection of IL-2-activated NK cells has been shown to promote vascular remodeling through a4b7 integrin and killer cell lectin-like receptor (KLRG)-1 and promote cardiac repair after MI [29,30][29][30]. In addition, Cao et al. have reported that IL-2 could reduce infarct size by activating kappa-opioid receptors [31]. Moreover, IL-2 can be stimulated by the IL-2IgG2b fusion protein to improve left ventricular (LV) contraction function and remodeling in an MI rat model [30]. In conclusion, additional experimental studies are needed to fully elucidate the role of IL-2 and develop its therapeutic potential in heart disease.2.3. IL-4

IL-4 is generally regarded as an anti-inflammatory cytokine. A recent study by Wan et al. showed that Vγ1+ γδT cells, as one of the main early producers of IL-4 after acute viral infection, protect the mouse heart from acute viral myocarditis. Moreover, the neutralization of IL-4 in mice led to exacerbations of acute myocarditis, confirming the IL-4-mediated Vγ1 protective mechanism [32]. This finding was further supported by another study on viral myocarditis, which showed elevated levels of IL-4 in mice with attenuated viral myocarditis and elevated levels of heart expression [33]. However, a contradictory finding was reported in the context of autoimmune myocarditis, where eosinophils are the predominant cell type in the heart expressing IL-4, and eosinophil-specific IL-4 deletion leads to improved cardiac function. In this regard, eosinophils have been shown to drive myocarditis progression to inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy (DCMi), and this process is mediated by IL-4 [34].2.4. IL-6

IL-6, as an upstream marker of inflammation, is independently associated with the risk of major adverse cardiovascular disease events, MI, HF, and cancer mortality stable coronary heart disease [35]. IL-6 and sIL-6R have been associated with AMI and cardiac injury; binding to trans-IL-6 receptors alters intracellular signaling, and blocking IL-6 receptor binding may be a causative factor in AMIs [36]. Hypothetically validated, the IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab reduces inflammation and the release of TnT in non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI). Therefore, IL-6 is a potential therapeutic target for MI [37]. Cytokine-specific action appears to be present in the excitatory–contraction coupling and TNF-α IL-6 modulates Ca2+ ATPase activity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in cardiomyocytes [38]. It was reported that the degradation of IL-6 mRNA inhibits the proinflammatory action in the stress-overloaded myocardium [39]. Moreover, the gene deletion of IL-6 improves cardiac function and weakens hypertrophy by eliminating the dependent effects of CaMKII on cardiomyocytes in the stress-overloaded myocardium [40]. In addition, in the model of LV remodeling after MI, a drug blockade of IL-6 through the administration of an anti-IL6R antibody weakens dilation and improves contraction function [41]. IL-6 can indirectly enhance the expression of iNOS, and excess nitric oxide may reduce myocardial contractility and may have toxic effects by triggering apoptosis [42]. IL-6 exerts negative inotropic action [43] and promotes a hypertrophy response in cardiomyocytes [44,45,46][44][45][46] through the gp130/STAT3 pathway, but can also enable protective action, mediated by mitochondrial function preservation [47]. Recombinant IL-6 induces a cytoprotective effect to prevent I/R damage and activates ERK1/2, JNK1/2, p38-MAPK, and PI3K without inducing STAT1/3 phosphorylation. These data suggest that the cardiomyocyte protective effect of IL-6 in I/R occurs through ERK1/2 and PI3K activation, but is not related to sIL-6R and JAK/STAT signaling [48].2.5. IL-8

IL-8 is important in the development of MI. Serum IL-8 concentrations show a transient increase in the very early stages of AMI [49]. Specific monoclonal antibodies that neutralize IL-8 significantly reduce the degree of necrosis in rabbit myocardial I/R injury models [50]. High levels of IL-8 in STEMI patients with HF are associated with less improvement in left ventricular function in the first 6 weeks after PCI, suggesting that IL-8 may play a role in reperfusion-related injuries to the myocardium after ischemia [51].2.6. IL-10

Cardioprotective effects of IL-10 on the cardiomyocytes of heart diseases were found in a variety of previous studies. The involvement of the Akt and Jak/Stat pathways in regulating TNF-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by IL-10 has been studied [52]. Subsequent research revealed that IL-10’s negative control of TNF-induced apoptosis was mediated by Akt via STAT3 activation [53]. In addition, there is a study revealing that IL-10-induced antiapoptotic signaling in cardiomyocytes includes upregulating TLR4 through MyD88 activation [54]. Moreover, Kishore, R et al. found that IL-10 attenuates pressure overload-induced hypertrophic remodeling and improves heart function via STAT3-dependent inhibition of NF-κB [55]. Exercise reduces HFD-induced cardiomyopathy by reducing obesity, inducing IL-10, and reducing TNF-α [56].2.7. IL-11

IL-11 mediates cytoprotective signals in cardiomyocytes by activating phosphorylated STAT3 translocating into nuclei [57]. IL-11 attenuated cardiac remodeling after MI through the gp130/STAT3 axis [5]. In addition, it also reduced the I/R injury through STAT3 activation in the hearts [58]. This evidence demonstrates the therapeutic role of IL-11 in heart disease.2.8. IL-17

As a proinflammatory cytokine, IL-17 participates in an array of heart diseases. IL-17 was reported to have contributed to the process of cardiac fibrosis, the activation of matrix metalloproteinases, and enhanced cardiac cell death. IL-17 induces mouse cardiomyocyte apoptosis via Stat3-iNOS activation, suggesting that IL-17 contributes to cardiac damage [59]. It has also been observed that IL-17A induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis through the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-p53-Bax signaling pathway and promotes both early- and late-phase post-MI ventricular remodeling [60]. Pan et al. found that IL-17 affects the calcium-handling process involved in HF. The treatment of neonatal cardiomyocytes with steady-state concentrations of IL-17 suppressed transient calcium and decreased SERCA2a and Cav1.2 expression, this effect is mediated via the NF-κB pathway [61].2.9. IL-18

IL-18 is a proinflammatory cytokine produced during various heart diseases. IL-18 was discovered to be elevated in animal models of AMI, HF, pressure overload, and LPS-induced dysfunction. Furthermore, IL-18 has been shown to regulate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, induce cardiac systolic dysfunction, and lead to extracellular matrix remodeling [62,63][62][63]. Several observations suggest that IL-18BP is a potential therapeutic tool for reducing myocardial dysfunction caused by ischemia [64,65,66][64][65][66]. The treatment of HL-1 cardiomyocytes with IL-18 resulted in hypertrophy and elevated levels of ANP, likely via the activation of signaling pathways involving PI3K, Akt, and the transcription factor GATA4 [67]. In vitro studies found that the IL-18 treatment of cardiomyocytes increased peak and diastolic calcium transients and decreased the shortening of isolated cardiomyocytes [68]. Moreover, an increase in serum IL-18 concentration may induce apoptosis in cardiomyocytes, leading to ongoing myocardial injury in acute MI [69]. However, there are some controversial studies; for example, the expression of IL-18RNA in the myocardium of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy is downregulated [70], and IL-18 has been shown to play a beneficial role in viral myocarditis caused by the cerebrocarditis virus. The systemic administration of IL-18 is beneficial in mice with myocarditis and may be mediated by reducing the expression of TNF-α in the heart [65]. Overall, the role of IL-18 in heart disease is primarily in amplifying myocardial dysfunction, and the level also was recognized as a marker of heart injury in patients.2.10. IL-33

IL-33 belongs to the IL-1 family. IL-33 and its receptor ST2 (located on the membrane of CMs) were demonstrated to be cardioprotective. The highly localized signaling pathway mediated by ST2 regulates the heart’s response to pressure overload. It was suggested that IL-33 secretion by endothelial cells is crucial in converting myocardial pressure overload into a selective systemic inflammatory state [71]. In a study involving wild-type mice, treatment with recombinant IL-33 was found to reduce angiotensin II and phenylephrine-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and fibrosis. Furthermore, IL-33 treatment improved survival after transverse aortic constriction (TAC), a surgical procedure used to induce cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure in animal models [72].2.11. IL-37

IL-37, like IL-10, is an anti-inflammatory interleukin generated by a variety of cell types. IL-37 is the main cytokine in the regulation of immune response, mainly inhibits the expression, production, and effect of proinflammatory cytokines, and plays a role in autoimmune diseases and organ transplantation [73]. The expression level of IL-37 is known to be low under normal physiological conditions; however, the expression level of IL-37 is significantly upregulated in response to an inflammatory environment, such as in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) [74]. IL-37 plays an active role in a variety of cardiovascular diseases [75]. The Zeng group reported that human recombinant IL-37 can inhibit neutrophil infiltration and reduce cardiomyocyte apoptosis through a tail vein injection into myocardial I/R mice, thereby alleviating myocardial I/R injury in mice [76]. The team also reported that the intraperitoneal injection of human recombinant IL-37 and the intravenous injection of IL-37 and troponin co-induced dendritic cells can alleviate adverse ventricular remodeling after MI and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in mice, also attenuating the degree of cardiac fibrosis [77]. Overall, the positive role of IL-37 on other heart diseases, i.e., HF, needs to be further elucidated. Overall, the effects of interleukins on CMs in heart disease are complex and context-dependent, and more research is needed to fully understand their roles in these conditions.References

- Benjamin, E.J.; Blaha, M.J.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M.; Das, S.R.; Deo, R.; de Ferranti, S.D.; Floyd, J.; Fornage, M.; Gillespie, C.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135, e146–e603.

- Bartekova, M.; Radosinska, J.; Jelemensky, M.; Dhalla, N.S. Role of cytokines and inflammation in heart function during health and disease. Heart Fail. Rev. 2018, 23, 733–758.

- Litvinukova, M.; Talavera-Lopez, C.; Maatz, H.; Reichart, D.; Worth, C.L.; Lindberg, E.L.; Kanda, M.; Polanski, K.; Heinig, M.; Lee, M.; et al. Cells of the adult human heart. Nature 2020, 588, 466–472.

- Schafer, S.; Viswanathan, S.; Widjaja, A.A.; Lim, W.W.; Moreno-Moral, A.; DeLaughter, D.M.; Ng, B.; Patone, G.; Chow, K.; Khin, E.; et al. IL-11 is a crucial determinant of cardiovascular fibrosis. Nature 2017, 552, 110–115.

- Obana, M.; Maeda, M.; Takeda, K.; Hayama, A.; Mohri, T.; Yamashita, T.; Nakaoka, Y.; Komuro, I.; Takeda, K.; Matsumiya, G.; et al. Therapeutic activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 by interleukin-11 ameliorates cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2010, 121, 684–691.

- Garlanda, C.; Dinarello, C.A.; Mantovani, A. The interleukin-1 family: Back to the future. Immunity 2013, 39, 1003–1018.

- Liao, W.; Lin, J.X.; Leonard, W.J. IL-2 family cytokines: New insights into the complex roles of IL-2 as a broad regulator of T helper cell differentiation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2011, 23, 598–604.

- Shintani, Y.; Ito, T.; Fields, L.; Shiraishi, M.; Ichihara, Y.; Sato, N.; Podaru, M.; Kainuma, S.; Tanaka, H.; Suzuki, K. IL-4 as a Repurposed Biological Drug for Myocardial Infarction through Augmentation of Reparative Cardiac Macrophages: Proof-of-Concept Data in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6877.

- Feng, Y.; Ye, D.; Wang, Z.; Pan, H.; Lu, X.; Wang, M.; Xu, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, M.; et al. The Role of Interleukin-6 Family Members in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 818890.

- Apostolakis, S.; Vogiatzi, K.; Amanatidou, V.; Spandidos, D.A. Interleukin 8 and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 84, 353–360.

- Mora-Ruiz, M.D.; Blanco-Favela, F.; Chavez Rueda, A.K.; Legorreta-Haquet, M.V.; Chavez-Sanchez, L. Role of interleukin-17 in acute myocardial infarction. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 107, 71–78.

- Saxena, A.; Russo, I.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Inflammation as a therapeutic target in myocardial infarction: Learning from past failures to meet future challenges. Transl. Res. 2016, 167, 152–166.

- Evans, H.G.; Lewis, M.J.; Shah, A.M. Interleukin-1β modulates myocardial contraction via dexamethasone sensitive production of nitric oxide. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993, 27, 1486–1490.

- Mauro, A.G.; Mezzaroma, E.; Torrado, J.; Kundur, P.; Joshi, P.; Stroud, K.; Quaini, F.; Lagrasta, C.A.; Abbate, A.; Toldo, S. Reduction of Myocardial Ischemia—Reperfusion Injury by Inhibiting Interleukin-1α. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 156–160.

- Lugrin, J.; Parapanov, R.; Rosenblatt-Velin, N.; Rignault-Clerc, S.; Feihl, F.; Waeber, B.; Muller, O.; Vergely, C.; Zeller, M.; Tardivel, A.; et al. Cutting edge: IL-1α is a crucial danger signal triggering acute myocardial inflammation during myocardial infarction. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 499–503.

- Cavalli, G.; Colafrancesco, S.; Emmi, G.; Imazio, M.; Lopalco, G.; Maggio, M.C.; Sota, J.; Dinarello, C.A. Interleukin 1α: A comprehensive review on the role of IL-1α in the pathogenesis and treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102763.

- Schreur, K.D.; Liu, S. Involvement of ceramide in inhibitory effect of IL-1β on L-type Ca2+ current in adult rat ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 272, H2591–H2598.

- Liu, S.; Schreur, K.D. G protein-mediated suppression of L-type Ca2+ current by interleukin-1β in cultured rat ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1995, 268, C339–C349.

- Li, Y.-H.; Rozanski, G.J. Effects of human recombinant interleukin-1 on electrical properties of guinea pig ventricular cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993, 27, 525–530.

- Kumar, A.; Thota, V.; Dee, L.; Olson, J.; Uretz, E.; Parrillo, J.E. Tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin 1β are responsible for in vitro myocardial cell depression induced by human septic shock serum. J. Exp. Med. 1996, 183, 949–958.

- Gulick, T.; Chung, M.K.; Pieper, S.J.; Lange, L.G.; Schreiner, G.F. Interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor inhibit cardiac myocyte β-adrenergic responsiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 6753–6757.

- Liu, S.J.; Zhou, W.; Kennedy, R.H. Suppression of β-adrenergic responsiveness of L-type Ca2+ current by IL-1β in rat ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 276, H141–H148.

- Combes, A.; Frye, C.S.; Lemster, B.H.; Brooks, S.S.; Watkins, S.C.; Feldman, A.M.; McTiernan, C.F. Chronic exposure to interleukin 1β induces a delayed and reversible alteration in excitation-contraction coupling of cultured cardiomyocytes. Pflügers Arch. 2002, 445, 246–256.

- Ing, D.J.; Zang, J.; Dzau, V.J.; Webster, K.A.; Bishopric, N.H. Modulation of Cytokine-Induced Cardiac Myocyte Apoptosis by Nitric Oxide, Bak, and Bcl-X. Circ. Res. 1999, 84, 21–33.

- Weisensee, D.; Bereiter-Hahn, J.; Schoeppe, W.; Löw-Friedrich, I. Effects of cytokines on the contractility of cultured cardiac myocytes. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1993, 15, 581–587.

- Eisner, R.M.; Husain, A.; Clark, J.I. Case report and brief review: IL-2-induced myocarditis. Cancer Investig. 2004, 22, 401–404.

- Cao, C.M.; Xia, Q.; Bruce, I.C.; Shen, Y.L.; Ye, Z.G.; Lin, G.H.; Chen, J.Z.; Li, G.R. Influence of interleukin-2 on Ca2+ handling in rat ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2003, 35, 1491–1503.

- Marriott, J.; Goldman, J.H.; Keeling, P.J.; Baig, M.K.; Dalgleish, A.; McKenna, W. Abnormal cytokine profiles in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and their asymptomatic relatives. Heart 1996, 75, 287–290.

- Bouchentouf, M.; Williams, P.; Forner, K.A.; Cuerquis, J.; Michaud, V.; Paradis, P.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Galipeau, J. Interleukin-2 enhances angiogenesis and preserves cardiac function following myocardial infarction. Cytokine 2011, 56, 732–738.

- Koch, M.; Savvatis, K.; Scheeler, M.; Dhayat, S.; Bonaventura, K.; Pohl, T.; Riad, A.; Bulfone-Paus, S.; Schultheiss, H.P.; Tschope, C. Immunosuppression with an interleukin-2 fusion protein leads to improved LV function in experimental ischemic cardiomyopathy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2010, 10, 207–212.

- Cao, C.M.; Xia, Q.; Tu, J.; Chen, M.; Wu, S.; Wong, T.M. Cardioprotection of interleukin-2 is mediated via kappa-opioid receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 309, 560–567.

- Wan, F.; Yan, K.; Xu, D.; Qian, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, M.; Xu, W. Vγ1(+)γδT, early cardiac infiltrated innate population dominantly producing IL-4, protect mice against CVB3 myocarditis by modulating IFNγ(+) T response. Mol. Immunol. 2017, 81, 16–25.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Tang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhong, M.; Suo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, K. Silencing MicroRNA-155 Attenuates Cardiac Injury and Dysfunction in Viral Myocarditis via Promotion of M2 Phenotype Polarization of Macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22613.

- Diny, N.L.; Baldeviano, G.C.; Talor, M.V.; Barin, J.G.; Ong, S.; Bedja, D.; Hays, A.G.; Gilotra, N.A.; Coppens, I.; Rose, N.R.; et al. Eosinophil-derived IL-4 drives progression of myocarditis to inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 943–957.

- Held, C.; White, H.D.; Stewart, R.A.H.; Budaj, A.; Cannon, C.P.; Hochman, J.S.; Koenig, W.; Siegbahn, A.; Steg, P.G.; Soffer, J.; et al. Inflammatory Biomarkers Interleukin-6 and C-Reactive Protein and Outcomes in Stable Coronary Heart Disease: Experiences from the Stability (Stabilization of Atherosclerotic Plaque by Initiation of Darapladib Therapy) Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 214, 943–957.

- Anderson, D.R.; Poterucha, J.T.; Mikuls, T.R.; Duryee, M.J.; Garvin, R.P.; Klassen, L.W.; Shurmur, S.W.; Thiele, G.M. IL-6 and its receptors in coronary artery disease and acute myocardial infarction. Cytokine 2013, 62, 395–400.

- Kleveland, O.; Kunszt, G.; Bratlie, M.; Ueland, T.; Broch, K.; Holte, E.; Michelsen, A.E.; Bendz, B.; Amundsen, B.H.; Espevik, T.; et al. Effect of a single dose of the interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab on inflammation and troponin T release in patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2406–2413.

- Sugishita, K.; Kinugawa K-i Shimizu, T.; Harada, K.; Matsui, H.; Takahashi, T.; Serizawa, T.; Kohmoto, O. Cellular basis for the acute inhibitory effects of IL-6 and TNF-α on excitation-contraction coupling. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1999, 31, 1457–1467.

- Omiya, S.; Omori, Y.; Taneike, M.; Murakawa, T.; Ito, J.; Tanada, Y.; Nishida, K.; Yamaguchi, O.; Satoh, T.; Shah, A.M. Cytokine mRNA degradation in cardiomyocytes restrains sterile inflammation in pressure-overloaded hearts. Circulation 2020, 141, 667–677.

- Zhao, L.; Cheng, G.; Jin, R.; Afzal, M.R.; Samanta, A.; Xuan, Y.T.; Girgis, M.; Elias, H.K.; Zhu, Y.; Davani, A.; et al. Deletion of Interleukin-6 Attenuates Pressure Overload-Induced Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Dysfunction. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1918–1929.

- Kobara, M.; Noda, K.; Kitamura, M.; Okamoto, A.; Shiraishi, T.; Toba, H.; Matsubara, H.; Nakata, T. Antibody against interleukin-6 receptor attenuates left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction in mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 87, 424–430.

- Roig, E.; Orús, J.; Paré, C.; Azqueta, M.; Filella, X.; Perez-Villa, F.; Heras, M.; Sanz, G. Serum interleukin-6 in congestive heart failure secondary to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 1998, 82, 688–690.

- Kinugawa, K.-I.; Takahashi, T.; Kohmoto, O.; Yao, A.; Aoyagi, T.; Momomura S-i Hirata, Y.; Serizawa, T. Nitric oxide-mediated effects of interleukin-6 on i and cell contraction in cultured chick ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 1994, 75, 285–295.

- Melendez, G.C.; McLarty, J.L.; Levick, S.P.; Du, Y.; Janicki, J.S.; Brower, G.L. Interleukin 6 mediates myocardial fibrosis, concentric hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction in rats. Hypertension 2010, 56, 225–231.

- Sano, M.; Fukuda, K.; Kodama, H.; Pan, J.; Saito, M.; Matsuzaki, J.; Takahashi, T.; Makino, S.; Kato, T.; Ogawa, S. Interleukin-6 family of cytokines mediate angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rodent cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 29717–29723.

- Kunisada, K.; Tone, E.; Fujio, Y.; Matsui, H.; Yamauchi-Takihara, K.; Kishimoto, T. Activation of gp130 transduces hypertrophic signals via STAT3 in cardiac myocytes. Circulation 1998, 98, 346–352.

- Smart, N.; Mojet, M.H.; Latchman, D.S.; Marber, M.S.; Duchen, M.R.; Heads, R.J. IL-6 induces PI 3-kinase and nitric oxide-dependent protection and preserves mitochondrial function in cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 69, 164–177.

- Fahmi, A.; Smart, N.; Punn, A.; Jabr, R.; Marber, M.; Heads, R. p42/p44-MAPK and PI3K are sufficient for IL-6 family cytokines/gp130 to signal to hypertrophy and survival in cardiomyocytes in the absence of JAK/STAT activation. Cell Signal. 2013, 25, 898–909.

- Abe, Y.; Kawakami, M.; Kuroki, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Fujii, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Yaginuma, T.; Kashii, A.; Saito, M.; Matsushima, K. Transient rise in serum interleukin-8 concentration during acute myocardial infarction. Heart 1993, 70, 132–134.

- Boyle, E.M., Jr.; Kovacich, J.C.; Hèbert, C.A.; Canty, T.G., Jr.; Chi, E.; Morgan, E.N.; Pohlman, T.H.; Verrier, E.D. Inhibition of interleukin-8 blocks myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1998, 116, 114–121.

- Husebye, T.; Eritsland, J.; Arnesen, H.; Bjornerheim, R.; Mangschau, A.; Seljeflot, I.; Andersen, G.O. Association of interleukin 8 and myocardial recovery in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction complicated by acute heart failure. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112359.

- Dhingra, S.; Sharma, A.K.; Singla, D.K.; Singal, P.K. p38 and ERK1/2 MAPKs mediate the interplay of TNFα and IL-10 in regulating oxidative stress and cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 293, H3524–H3531.

- Dhingra, S.; Bagchi, A.K.; Ludke, A.L.; Sharma, A.K.; Singal, P.K. Akt regulates IL-10 mediated suppression of TNFα-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by upregulating Stat3 phosphorylation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25009.

- Bagchi, A.K.; Sharma, A.; Dhingra, S.; Lehenbauer Ludke, A.R.; Al-Shudiefat, A.A.; Singal, P.K. Interleukin-10 activates Toll-like receptor 4 and requires MyD88 for cardiomyocyte survival. Cytokine 2013, 61, 304–314.

- Verma, S.K.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Barefield, D.; Singh, N.; Gupta, R.; Lambers, E.; Thal, M.; Mackie, A.; Hoxha, E.; Ramirez, V.; et al. Interleukin-10 treatment attenuates pressure overload-induced hypertrophic remodeling and improves heart function via signal transducers and activators of transcription 3-dependent inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB. Circulation 2012, 126, 418–429.

- Kesherwani, V.; Chavali, V.; Hackfort, B.T.; Tyagi, S.C.; Mishra, P.K. Exercise ameliorates high fat diet induced cardiac dysfunction by increasing interleukin 10. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 124.

- Kimura, R.; Maeda, M.; Arita, A.; Oshima, Y.; Obana, M.; Ito, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Mohri, T.; Kishimoto, T.; Kawase, I.; et al. Identification of cardiac myocytes as the target of interleukin 11, a cardioprotective cytokine. Cytokine 2007, 38, 107–115.

- Obana, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Murasawa, S.; Iwakura, T.; Hayama, A.; Yamashita, T.; Shiragaki, M.; Kumagai, S.; Miyawaki, A.; Takewaki, K.; et al. Therapeutic administration of IL-11 exhibits the postconditioning effects against ischemia-reperfusion injury via STAT3 in the heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 303, H569–H577.

- Su, S.A.; Yang, D.; Zhu, W.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.A.; Xiang, M. Interleukin-17A mediates cardiomyocyte apoptosis through Stat3-iNOS pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 2784–2794.

- Zhou, S.F.; Yuan, J.; Liao, M.Y.; Xia, N.; Tang, T.T.; Li, J.J.; Jiao, J.; Dong, W.Y.; Nie, S.F.; Zhu, Z.F.; et al. IL-17A promotes ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 92, 1105–1116.

- Xue, G.L.; Li, D.S.; Wang, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.M.; Li, C.Z.; Li, X.D.; Ma, J.D.; Zhang, M.M.; Lu, Y.J.; et al. Interleukin-17 upregulation participates in the pathogenesis of heart failure in mice via NF-kappaB-dependent suppression of SERCA2a and Cav1.2 expression. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 1780–1789.

- Reidar Woldbaek, P. Increased cardiac IL-18 mRNA, pro-IL-18 and plasma IL-18 after myocardial infarction in the mouse: A potential role in cardiac dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003, 59, 122–131.

- Yamaoka-Tojo, M.; Tojo, T.; Inomata, T.; Machida, Y.; Osada, K.; Izumi, T. Circulating levels of interleukin 18 reflect etiologies of heart failure: Th1/Th2 cytokine imbalance exaggerates the pathophysiology of advanced heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 2002, 8, 21–27.

- Gluck, B.; Schmidtke, M.; Merkle, I.; Stelzner, A.; Gemsa, D. Persistent expression of cytokines in the chronic stage of CVB3-induced myocarditis in NMRI mice. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001, 33, 1615–1626.

- Yoshida, A.; Kanda, T.; Tanaka, T.; Yokoyama, T.; Kurimoto, M.; Tamura, J.I.; Kobayashi, I. Interleukin-18 reduces expression of cardiac tumor necrosis factor-α and atrial natriuretic peptide in a murine model of viral myocarditis. Life Sci. 2002, 70, 1225–1234.

- Pomerantz, B.J.; Reznikov, L.L.; Harken, A.H.; Dinarello, C.A. Inhibition of caspase 1 reduces human myocardial ischemic dysfunction via inhibition of IL-18 and IL-1β. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 2871–2876.

- Chandrasekar, B.; Mummidi, S.; Claycomb, W.C.; Mestril, R.; Nemer, M. Interleukin-18 is a pro-hypertrophic cytokine that acts through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1-Akt-GATA4 signaling pathway in cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 4553–4567.

- Woldbaek, P.R.; Sande, J.B.; Stromme, T.A.; Lunde, P.K.; Djurovic, S.; Lyberg, T.; Christensen, G.; Tonnessen, T. Daily administration of interleukin-18 causes myocardial dysfunction in healthy mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 289, H708–H714.

- Seta, Y.; Kanda, T.; Tanaka, T.; Arai, M.; Sekiguchi, K.; Yokoyama, T.; Kurimoto, M.; Tamura, J.I.; Kurabayashi, M. Interleukin 18 in acute myocardial infarction. Heart 2000, 84, 668–669.

- Westphal, E.; Rohrbach, S.; Buerke, M.; Behr, H.; Darmer, D.; Silber, R.E.; Werdan, K.; Loppnow, H. Altered interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and interleukin-18 mRNA expression in myocardial tissues of patients with dilatated cardiomyopathy. Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 55–63.

- Chen, W.Y.; Hong, J.; Gannon, J.; Kakkar, R.; Lee, R.T. Myocardial pressure overload induces systemic inflammation through endothelial cell IL-33. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7249–7254.

- Sanada, S.; Hakuno, D.; Higgins, L.J.; Schreiter, E.R.; McKenzie, A.N.; Lee, R.T. IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1538–1549.

- Nold, M.F.; Nold-Petry, C.A.; Zepp, J.A.; Palmer, B.E.; Bufler, P.; Dinarello, C.A. IL-37 is a fundamental inhibitor of innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 1014–1022.

- Ji, Q.; Zeng, Q.; Huang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lu, Z.; Meng, K.; Wu, B.; Yu, K.; Chai, M.; et al. Elevated plasma IL-37, IL-18, IL-18BP concentrations in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 165742.

- Zhuang, X.; Wu, B.; Li, J.; Shi, H.; Jin, B.; Luo, X. The emerging role of interleukin-37 in cardiovascular diseases. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2017, 5, 373–379.

- Wu, B.; Meng, K.; Ji, Q.; Cheng, M.; Yu, K.; Zhao, X.; Tony, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chang, C.; et al. Interleukin-37 ameliorates myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014, 176, 438–451.

- Zhu, R.; Sun, H.; Yu, K.; Zhong, Y.; Shi, H.; Wei, Y.; Su, X.; Xu, W.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, F.; et al. Interleukin-37 and Dendritic Cells Treated with Interleukin-37 Plus Troponin I Ameliorate Cardiac Remodeling After Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 176, 438–451.

More