Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is a rare, aggressive mesenchymal tumor with smooth muscle differentiation. LMS is one of the most common histologic subtypes of soft tissue sarcoma; it most frequently occurs in the extremities, retroperitoneum, or uterus. LMS often demonstrates aggressive tumor biology, with a higher risk of developing distant metastatic disease than most sarcoma histologic types.

- leiomyosarcoma

- immune microenvironment

- immune-checkpoint blockade

1. Introduction

2. Current Standard of Care Treatment for LMS

LMS should be treated in specialized cancer centers, as it has demonstrated a significant survival benefit [19][20][21][19,20,21]. Pretreatment biopsy is mandatory, with core biopsy as the preferred technique to ensure minimal tissue disruption while simultaneously providing ample tissue for pathologic assessment [3][22][3,22]. Surgical resection is the cornerstone treatment for localized LMS, independent of the site of origin [22][23][22,23]. The goal of resection is to achieve complete surgical excision with negative microscopic margins. Overall, LMS is among the most chemosensitive of STS types, and neoadjuvant doxorubicin-based chemotherapy is recommended for large (>5 cm) intermediate- to high-grade extremity and uterine LMS [22][23][24][22,23,24] and under investigation for retroperitoneal LMS (NCT04031677). The efficacy of doxorubicin-combination regimens and their application in LMS were largely informed by the results of landmark studies and meta-analyses performed in the late 20th and early 21st century in studies of mixed STS types [25][26][25,26]. The use of standard chemotherapy agents, namely doxorubicin-based regimens, alone and in combination with other cytotoxic drugs in the first-line setting, offers median OS durations of approximately 12–18 months and overall response rates (ORRs) of 20–30% [27][28][27,28] in metastatic or relapsed uLMS and ST-LMS [22][23][22,23]. Overall, gemcitabine in combination with other agents constitutes a valuable alternative for patients with LMS whose disease has progressed after the failure of prior standard chemotherapy with doxorubicin [22][23][24][22,23,24]. Hensley et al. [29] evaluated the combination of gemcitabine plus docetaxel in 34 patients with both uLMS (29 of 34) and ST-LMS (5 of 34) who had all previously progressed on prior chemotherapy and found an ORR of 53%. Further study of the combination of gemcitabine plus docetaxel versus gemcitabine alone in pretreated LMS validated the synergistic cytotoxicity of this combination in prolonging stable disease, albeit with higher rates of treatment-associated toxicity [30]. Trabectedin, a synthetic antineoplastic drug, has been observed to have efficacy in both ST-LMS and uLMS in clinical trials, specifically in patients who have exhausted standard chemotherapy [31][32][31,32]. Trabectedin was investigated in a phase III multicenter randomized controlled study in advanced liposarcomas and LMS after failure of doxorubicin: 518 patients were randomized to receive trabectedin (n = 345) or dacarbazine (n = 173). Trabectedin demonstrated a significant increase in PFS compared to dacarbazine (4.2 months versus 1.5 months, p < 0.001) [33]. Doxorubicin in combination with trabectedin was evaluated in a recently reported randomized, multicenter, phase III trial (LMS-04) conducted at 20 centers of the French Sarcoma Group [12]. The study included adult patients with metastatic or relapsed unresectable uLMS (n = 67) or ST-LMS (n = 83) who had not been previously treated with chemotherapy. Patients were assigned to receive either doxorubicin alone or doxorubicin plus trabectedin. The median PFS duration was significantly longer with doxorubicin plus trabectedin versus doxorubicin alone (12.2 months [95% CI, 10.1–15.6] vs. 6.2 months [95% CI, 4.1–7.1]; p < 0.0001). To evaluate the tolerability of pazopanib, an oral angiogenesis multikinase inhibitor that targets VEGF, PDGF, and c-kit, Sleijfer et al. [34] accrued 142 patients, 42 of whom had high- or intermediate-grade advanced LMS that had received previous therapy. The study observed that 44% of LMS patients were progression-free at 12 weeks after the start of treatment and the median OS duration was ~1 year, with well-tolerated toxicity profiles. Pazopanib was further explored in STS in a phase III study (PALETTE) including 369 patients from 72 institutions worldwide with metastatic or progressive STS, who had undergone at least one regimen containing anthracycline; patients were randomly assigned to pazopanib vs. placebo in a 2:1 ratio, with 44% (n = 109) of LMS patients. The trial demonstrated that pazopanib significantly increased the PFS duration by a median of 3 months compared with placebo [35].2.1. uLMS-Specific Considerations

Incomplete hysterectomy and morcellation have been associated with reduced overall and intra-abdominal recurrence rates as well as death rates compared to complete hysterectomy [36]. Radiation therapy after resection of localized uLMS has been evaluated in several retrospective analyses. A randomized phase III trial conducted by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) evaluated the impact of RT on local control whereby 103 patients with stage I and II uLMS disease were randomly assigned to receive adjuvant pelvic radiation therapy (50.4 cGy in 28 fractions over 5 weeks) or observation. No differences were observed in OS or disease-free survival (DFS) [37]. Therefore, adjuvant radiation therapy is generally not recommended [38] in localized uLMS. Although no trial has formally shown that adjuvant chemotherapy has an OS benefit in LMS, perioperative chemotherapy remains the standard of care for uLMS [39][40][39,40]. A prospective randomized phase III study, which was halted because of a lack of recruitment, reported a significantly higher 3-year DFS rate (55% vs. 41%) following the administration of polychemotherapy consisting of doxorubicin/ifosfamide/cisplatin in addition to radiation therapy, but this had no effect on OS [41]. A consecutive prospective one-arm phase II study showed a longer DFS (3-year DFS rate, 57%) in LMS limited to only the uteruses that were treated with gemcitabine plus docetaxel followed by doxorubicin than in historical controls [18].2.2. ST-LMS-Specific Considerations

Complete resection is essential for management of patients with localized disease and may be accomplished by limiting dissection to uninvolved tissue planes and resecting the tumor en bloc with wide margins—including, when possible, at least one uninvolved tissue plane circumferentially [42][43][42,43]. Incomplete resection has consistently been associated with local and distant ST-LMS recurrences in large series [43][44][43,44] and has been demonstrated to be a predictor of poor survival [44][45][44,45]. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy are important adjuncts in the treatment of ST-LMS. A recent systematic meta-analysis of 16 studies (n = 3958) indicated that external beam radiation therapy reduced local recurrence in patients with STS of the extremities, head and neck, or trunk wall. Additionally, local recurrence rates were lower for preoperative radiation therapy than for postoperative radiation therapy [46]. The prospective EORTC-62092 (STRASS) randomized, phase III study, evaluated 266 patients with localized retroperitoneal sarcoma, 20% of whom had ST-LMS; no benefit was demonstrated in terms of RFS or OS in patients treated with neoadjuvant radiation therapy and surgery vs. surgery alone [47].3. Molecular Landscape of LMS

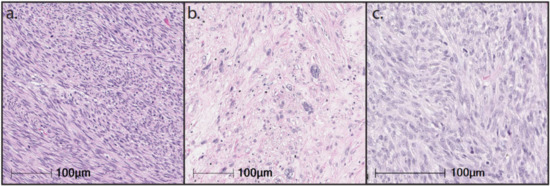

LMS encompasses tumors that exhibit a wide range of differentiation with progressive loss of muscle markers extending from well-differentiated to poorly differentiated LMS that resembles UPS. The morphology of LMS and the expression of muscle markers are significant prognostic factors [7]. LMS are genomically complex tumors, with frequent alterations of TP53 (80%), RB1 (80%), and PTEN (80%) [48][49][65,66], and can be subtyped into three genomically distinct clusters: a uLMS subtype and two soft tissue LMS (ST-LMS) subtypes [49][50][51][66,67,68]. The more dedifferentiated ST-LMS subtype is characterized by significantly higher genomic instability more closely resembling UPS and by significantly worse OS. These genomically distinct clusters have significant phenotypic and morphological differences (Figure 1). In this section, we detail the molecular hallmarks of LMS and their potential effect on the tumor immune microenvironment.

3.1. Complex Karyotype

The karyotype of LMS is genomically complex, with multiple genes that are frequently altered to varying degrees and no pathognomonic chromosomic alteration. Overall, LMS has a lower tumor mutational burden (median of 2.61 mutations/Mb [52][53][69,70]) and fewer somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) than other complex genomic sarcomas. A higher tumor mutational burden is associated with improved response and survival following ICB [54][55][56][71,72,73]; however, a higher number of SCNAs have been associated with resistance to ICB [57][74]. Both uLMS and ST-LMS demonstrate fewer SCNAs than more immune-sensitive complex sarcomas, such as UPS [49][66]. SCNAs have been shown to support tumorigenesis and propagate mutagenic processes that drive genomic instability during tumor growth [58][75]. While some focal SCNAs appear to be preserved across multiple cancer histologies, investigation into LMS has failed to reveal conserved or recurrent copy number alterations [59][76]. Instead, LMS SCNAs are often highly variable and are characterized by a predominance of deletions [53][60][70,77]. Notable among these deletions are genes involved in cell cycle progression and DNA damage repair at rates similar to those found in UPS [59][76]. A pan-sarcoma molecular analysis of LMS identified deep deletions in TP53, RB1, and CDKN2A among 9%, 14%, and 8% of LMS [49][66]. This complex karyotype may inform resistance to ICB because of a paucity of targetable neoantigens and recurrent genetic alterations [61][62][63][78,79,80].3.2. Molecular Subtypes of LMS

ST-LMS and uLMS are molecularly distinct—despite their histologic and karyotypic similarities, they have different methylation and mRNA expression signatures [49][66]. Initial work to characterize the molecular profile of LMS by Beck et al. used comparative genomic hybridization arrays to cluster LMS into three reproducible subtypes [50][67]. Extrauterine tumors, which comprised molecular subtypes I and II, tended to have pathways that were enriched for genes encoding muscle differentiation, protein metabolism, and regulation of cellular proliferation. In contrast, uterine tumors, which comprise molecular subtype III, tended to have pathways enriched for genes encoding metal binding, wound response, and ribosomal function and protein synthesis. Further work by Guo et al. recapitulated these three molecular subtypes; these authors also identified specific gene signatures enriched within each subtype. Subtype I tumors more frequently overexpressed LMOD1, CALD1, and MYOCD, which are known to be involved with smooth muscle function and differentiation [64][81]. These findings suggest that subtype I represents a more well-differentiated molecular subtype that is more closely associated with normal smooth muscle function. By contrast, subtype II demonstrated significantly fewer muscle-specific genes than did subtype II and may indicate a more dedifferentiated molecular subtype. Importantly, this dedifferentiated subtype was shown to cluster with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas (UPS). Finally, subtype III was composed almost entirely of uLMS, with 92% of subtype III samples derived from the uterus. Genes enriched in subtype III govern biological processes regulating transcription and metabolic processing and indicate that uLMS comprises a molecularly and clinically distinct cluster from ST-LMS.3.3. TP53

Investigations into frequent molecular alterations in LMS have largely focused on TP53 mutations, given its established role in oncogenesis among various cancer types [65][66][83,84]. TP53 encodes for p53, a known tumor suppressor that acts as a critical regulator of processes that govern progression through the cell cycle, DNA repair, apoptosis, and cellular senescence [67][85]. p53 has several metabolic functions that counteract oncogenesis and has been observed to suppress glycolysis and promote oxidative phosphorylation; this, in turn, inhibits glucose metabolism, which has been associated with malignant growth [67][85]. Metabolic stressors, such as depletion of nutrients or increasingly anaerobic conditions, may also activate p53, preventing tumor progression by driving apoptosis [68][86]. In this context, loss of p53 function is a common feature in a majority of human cancers, as up to 75% of mutations result in loss of wild-type function [69][87]. Accordingly, up to 80% of LMS demonstrate mutations in TP53. Chudasama et al. identified a multitude of chromosomal rearrangements of TP53 in 49% of their cohort of LMS samples through a variety of mechanisms, including out-of-frame fusions and loss of functional domains [60][77]. These genetic alterations resulted in TP53 mutations that clustered most commonly in the DNA binding and tetramerization motifs, indicating substantial heterogeneity in the mutational landscape that drives TP53 alterations. Notably, alterations in TP53 appear to be more common in extrauterine LMS, as Hensley et al. identified TP53 alterations in 71% of ST-LMS versus 56% of uLMS [70][88]. Among their cohort, the authors identified loss-of-function mutations and homozygous deletions as the most common mechanisms of TP53 alteration, particularly among uLMS, and noted that TP53 mutations were more common in LMS than in high-grade non-LMS. Notably, disruptions in TP53 appear to frequently accompany biallelic inactivation of RB1. Chudasama et al. observed biallelic inactivation in over 90% of cases, characterized by a heterogeneity of mechanisms, including protein-damaging microdeletions, inversion, and exon-skipping events [60][77]. A further genomic analysis identified that while RB1 is most often deleted, TP53 may be either deleted or mutated. Using the TCGA, Abeshouse et al. identified shallow deletions in 60% and 78% of TP53 and RB1, respectively [49][66]. However, mutations were identified in 50% and 15%, respectively, suggesting that while TP53 and RB1 are often co-altered in LMS, the exact mechanisms underlying these genetic aberrations may vary. Characterization of the intratumoral immune environment has revealed associations with several commonly mutated genes, particularly TP53. Petitprez et al. developed an immune-based classification system for STS through clustering of tumors based on transcriptomic immune signatures. In doing so, the authors observed a distinct cluster of tumors that was characterized by a higher density of immune infiltrate [71][89]. Mutations in TP53 were the most frequently observed genetic aberration among immune-rich groups, occurring in 35.2% of samples. On the basis of these findings, there may be an association between specific genetic alterations and the immune microenvironment, which may have substantial implications for response to ICB.3.4. RB1

Homozygous deletions in RB1 are among the most frequent genetic alterations identified in LMS, occurring in as many as 80% of samples [49][72][66,90]. RB1 encodes retinoblastoma 1 (Rb1), which is a well-described regulator of the cell cycle. Under physiologic conditions, mitogenic signals activate CDK4/6, which in turn complexes with D-type cyclins. These kinases phosphorylate and inactivate RB1, which then de-represses the E2F transcription factor and allows progression of the cell cycle [73][91]. Deletions in RB1, therefore, result in unchecked cellular proliferation and have been implicated in oncogenesis across a variety of human cancers. In addition, there has been emerging evidence of non-canonical roles of RB1 in tumor metabolism, the tumor microenvironment, and epigenetics; these pathways remain poorly understood, and the clinical implications are yet to be determined [73][74][75][91,92,93]. Fusion events affecting RB1 are less common than deletions but may represent a critical mechanism for driving tumorigenesis, particularly in uLMS. Choi et al. observed RB1 fusions in 30% of sampled uLMS by RNA-seq resulting in truncation of the RB1 protein and ultimately loss of function [76][94]. By contrast, fusion events affecting other known LMS driver genes were less commonly observed (8% TP53 and 8% ATRX). In addition, the rate of fusion events among ST-LMS appears less frequent. Liu et al. observed only one fusion event among their cohort of 20 ST-LMS patients, which is significantly lower than the 88% verified in their cohort of DDLPS patients. Fusion transcripts may be a source of neoantigen formation; in an in vitro analysis, fusion-associated neoantigens elicited cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell responses, even among cancers with low tumor mutational burden [77][95].3.5. PTEN Deletion and PI3k/AKt/mTOR Pathway

Multi-platform profiling has identified loss of PTEN expression in up to 32% and 38% of SMulti-platform profiling has identified loss of PTEN expression in up to 32% and 38% of ST and uLMS, respectively [116]. PTEN encodes a dual-phosphatase protein that inhibits AKT signaling, which activates the downstream mTOR pathway that inhibits cellular proliferation, cell growth, and metabolism and promotes susceptibility to apoptosis [117, 118]. As such, PTEN loss results in increased levels of PIP3 and an upregulated PI3k-Akt pathway that stimulates unchecked cell growth [119]. The most frequent mechanism of PTEN dysregulation is loss of chromosome 10q, which occurs in as many as 59% of LMS tumors in some studies; its loss may be correlated with more aggressive behavior and the development of metastatic disease [120].

The frequency of PTEN alterations appears to vary by anatomic location, disease stage, and analysis method. Zhang et al. used molecular analysis by PCR to identify PTEN deletions among 32% of primary uLMS samples [121]. These findings were recapitulated with a subsequent FISH analysis, and patients with PTEN loss were observed to have significantly worse OS than those who did not. Schaefer et al. observed PTEN protein loss by IHC in 41% and 31% of primary and non-primary uLMS, respectively [101], and 47% and 55% of primary and non-primary ST-LMS. Conversely, Chudasama et al. observed genomic deleterious aberrations in PTEN among 57% of LMS samples [88], but the authors did not specify the distribution of anatomic location or disease stage. These data suggest that aberrations in PTEN are a common, although non-unifying, feature of LMS and may represent a biomarker of aggressive tumor biology.

Bi-allelic loss of PTEN in LMS has become increasingly associated with resistance to ICB. In vitro experimentation suggests that this is a result of decreased neoantigen formation and subsequent reduction in T-cell immunoreactivity [122]. Therapeutic resistance may be a result of transcriptomic changes associated with biallelic PTEN loss, as treatment-resistant tumors have been observed to have significantly lower expression of genes associated with immunologically reactive cytokines, including PDCD1, CD8A, IFNG, and GZMA. In this context, a reduction in immunologic reactivity as a result of PTEN loss may also contribute to tumoral immune evasion and exclusion. Preclinical models using melanoma cell lines have demonstrated decreased T-cell infiltration in PTEN-silenced tumors and show that loss of PTEN upregulates inhibitory cytokines CCL2 and VEGF, both of which have been implicated in tumor immune evasion [123-125].

PTEN loss has been observed to be correlated with a significant reduction in PD-1+ cell infiltration within uLMS, particularly among metastatic lesions [122]. Treatment-resistant metastatic uLMS lesions have significant reductions in PD-1+ staining following anti-PD-1 therapy, with PD-1 positivity in less than <1% of overall cellularity. As aforementioned, these treatment-resistant lesions are genomically characterized by biallelic PTEN loss and upregulation of VEGFA; taken together, these data indicate that PTEN loss promotes an immunologically excluded tumor microenvironment through upregulation of inhibitory cytokines and downregulation of PD-1, suggesting that PTEN significantly mediates acquired resistance to ICB monotherapy [122].

3.6. DNA Damage Response

The use of next-generation sequencing has provided significant insight into the DNA damage repair signatures that are becoming increasingly identified among LMS [126]. These alterations in DNA damage repair mechanisms are characteristic genomic features that typically occur as a result of deficiencies in homologous recombination repair [127]. Chudasama et al. used whole-exome sequencing to demonstrate hallmarks of BRCAness in 90% of sequenced LMS, including deletions or other structural rearrangements in the genes governing homologous recombination repair [88]. Notable among these genes were PTEN in 57% of cases, BRCA2 in 53%, ATM in 22%, and BRCA1 in 10%. There seems to be a higher proportion of alterations in the DNA damage response genes in the uterine LMS than in soft-tissue LMS. Further, alterations in these genes has been associated with a lower OS in patients with LMS. There has been particular interest in exploring the therapeutic benefit of a given tumor’s BRCAness, as this particular phenotype has been associated with increased sensitivity to PARP inhibitors [128].

In addition to PARP inhibitor sensitivity, genomic instability resulting from DNA damage response deficiencies appears to modulate the tumor immune microenvironment. The presence of ongoing DNA damage and deficient DNA damage repair mechanisms has been observed to foster inflammatory signaling that results in intratumoral influx of immunosuppressive cells, particularly myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [129]. As a result of this immunosuppressive environment, DNA damage continues in the tumor microenvironment via persistent free radical release, ultimately facilitating cancer progression [130, 131]. The administration of PARP inhibitors has been observed to produce a more robust infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. This has been hypothesized to be a result of cytosolic DNA formation caused by double-strand DNA breaks generated by PARP inhibition, which results in increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines IL-2, TNFα, and IFNγ, leading to subsequent CD8+ T cell activation [132, 133]. In this context, PARP inhibition may facilitate a more susceptible immune microenvironment, providing a rationale for combination therapy with immune-checkpoint inhibition.

4. Immune Landscape of LMS

T and uLMS, respectively [78]. PTEN encodes a dual-phosphatase protein that inhibits AKT signaling, which activates the downstream mTOR pathway that inhibits cellular proliferation, cell growth, and metabolism and promotes susceptibility to apoptosis [79][80]. As such, PTEN loss r immune landscapesults in increased levels of PIP3 and an upregulated PI3k-Akt pathway that stimulates unchecked cell growof both [81]. SThe-LMS most frequent mechanism of PTEN andysregulation is loss of chromosome 10q, which occurs in as many as 59% of LMS tumors in some studies; its loss may be correlated with more aggressive behavior and the development of metastatic disease [82]. The frequency of PTEN aluLMS is characterations appears to vary by anatomic location, disease stage, and analysis method. Zhang et al. used molecular analysis by PCR to identify PTEN deletionzed by a lower dens among 32% of primary uLMS samples [83]. These findings were recapitulated with a subsequent FISH analysis, and patients with PTEN l oss were observed to have significantly worse OS than those who did not. Schaefer et al. observed PTEN protein loss by IHC in 41% and 31% of primary and non-primary uLMS, respectively intratumoral [72], and 47% and 55% of primary and non-primary ST-LMS. Conversely, Chudasama et al. observed genomic deleterious aberrations in PTEN among 57% of LMS sampune celles [60], but the authors did not specify the distribution of anatomic location or disease stage. These data suggest that aberrations infiltration than PTEN are a common, although non-unifying, feature of LMS and may represent a biomarker of aggressive tumor biology. Bi-allelier sarc loss of PTEN in LMS has become increasingly associated with resistance to ICB. In vitro experimentation suggests that this is a result of decreased neoantigen formation and subsequent reduction in T-cell immunoreactivity [84]. Therapeutic resi histologiestance may be a result of transcriptomic changes associated with biallelic PTEN lwith coss, as treatment-resistant tumors have been observed to have significantly lower expression ofplex karyotypes [66]. genes assHociated with immunologically reactive cytokines, including PDCD1, CD8A, IFNG, and GZMA. In this context, a reduction in iwever, mmunologic reactivity as a result of PTEN loss meculayr also contribute to tumoral immune evasion and exclusion. Preclinical models using melanoma cell lines have demonstrated decreased T-cell infiltration insubtyping of LMS PTEN-silenced tumors and show that loss of PTEN upregulates inhibitory cytokines CCL2 and VEGF, both of which have been implicated in tumor immune evasion [85][86][87]. PTEN loss s provided thas been observed to be correlated with a significant reduction in PD-1+ cell infiltration within uLMS, particularly among metastatic lesions [84]. Treatment- framework for moresistant metastatic uLMS lesions have significant reductions in PD-1+ staining following anti-PD-1 therapy, with PD-1 positivity in less than <1% of overall cellularity. As aforementioned, these treatment-resistant lesions are genomically characterized by biallelic PTEN lrigorous investigatioss and upregulation of VEGFA; intaken together, these data indicate that PTEN loss pro the imotes an immunologically excluded tumor me microenvironment through[67]. upregulation of inThibitory cytokines and downregulation of PD-1, suggesting that PTEN signifie presencantly mediates acquired resistance to ICB monotherapy [84].3.6. DNA Damage Response

The use o of next-generation sequencing has provided significant insight into the DNA damage repair signatures that are becoming increasingly identified among LMS [88]. Tertiary lymphese alterations in DNA damage repair mechanisms are characteristic genomic feaid structures that typically occur as a result of deficiencies in homologous recombination repair [89]. Chudaand PD-L1 hasama et al. used whole-exome sequencing to demonstrate hallmarks of BRCAness in 90% of sequenced LMS, including deletions or other structural rearrangements in the genes governing homologous recombination repair [60]. Notablgarnered increasing intere among sthese genes were PTEN in 57% of cases, BRCA2 in 53%, ATM in 22%, and BRCA1 in 10%. There seems to be a higher proportion of alterations in the DNA damage response genes in the uterine LMS than in soft-tissue LMS [90]. Further, alterativen their assons in these genes have been associated with a lower OS in patients with LMSion with [90]. There has been particular interest in exploring the therapeutic benefit of a given tumor’s BRCAness, as this ponse to ICB, particular phenotype has been associated with increased sensitivity to PARP inhibitors [91]. In ly in UPS addition to PARP inhibitor sensitivity, genomic instability resulting from DNA damage response deficiencies appears to modulate the tumor immune microenvironment. The presence of ongoing DNA damage and deficient DNA damage repair mechanisms has been observed to foster inflammatory signaling that results in intratumoral influx of immunosuppressive cells, particularly myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor-associated macrophagesd dedifferentiated liposarcoma [89,135]. (TAMs) [92]. As a result of this immunosuppressive environment, DNA damage continues in the tumor microenvironment via persistent free radical release, ultimately facilitating cancer progressionection thus outlines [93][94]. The administration of PARP inhibitors has been observed to produce a more robust infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. This has been hypothesized to be a result of cytosolic DNA formation caused by double-strand DNA breaks generated by PARP inhibition, which results in increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines IL-2, TNFα, and IFNγ, leading to subsequent CD8+ T-cell activation [95][96].4. Immune Landscape of LMS

The ie recurring characteristics of the LMS immune landscape of both ST-LMS and uLMS mis characterized by a lower density of intratumoral immune cell infiltration than other sarcoma histologies with complex karyotypes [49]. Hcroenvironment and details the burgeowever, molecular subtypning of LMS has provided the framework for more rigorous investigation into the immune microenvironmenttherapeutic [50]. The presence of tertiary lymphoid structures and PD-L1 has garnered increasing interest, given their association with response to ICB, particularly in UPS and dedifferentiated liposarcoma [71][97]tential of these molecular features.4.1. Tertiary Lymphoid Structures

The presence of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) in the tumor immune microenvironment has gained significant interest because of its association with response to ICB. Using transcriptomics data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Petitprez et al. observed that the immune microenvironment of sarcomas could be subtyped in to five distinct immune clusters, named sarcoma immune classes (SIC) ranging from SIC A (immune low) to SIC E (immune high). The SIC was further validated as a predictive biomarker of survival with ICB in the SARC028 trial, whereby patients with more immune-high SICs (E and D) had improved PFS and ORRs compared to immune-low SICs (A and B). The immune-rich SIC E tumors were characterized by high expression of the B lineage signature [71][89]. Notably, 82% of SIC E tumors were positive for intratumoral TLS by IHC, suggesting that TLS is a marker of effective antitumor immunity. On the basis of these data, there has been increasing interest in prospectively examining PD1 blockade in TLS-positive STS. Italiano et al. performed a multi-institutional phase II clinical trial examining pembrolizumab in TLS-positive STS across multiple histologic subtypes, including LMS. The authors observed a median PFS duration of 4.1 months and median OS of 18.3 months in TLS-positive tumors, which was longer than the median PFS of 1.4 months and median OS of 14.3 months in TLS-negative tumors [98][136]. A subsequent analysis using spatial deconvolution identified significantly increased enrichment of regulatory T cells among TLS-positive non-responders, suggesting that additional elements of the intratumoral immune infiltrate further modulate response to ICB. However, the authors note that TLS is infrequent in LMS, identifying TLS-positive tumors in 12.2% of ST-LMS samples. Petitprez et al. corroborated this observation, noting that most LMS clustered to the immune-low SIC A and B and demonstrated an overall paucity of intratumoral TLS [71][89]. As such, the utility of using TLS as a biomarker of response to ICB in LMS is crucial in screening for the +/−10% of patients who are more likely to respond to ICB monotherapy and those who may benefit from combinatorial approaches. Since dedifferentiated ST-LMS more closely resemble UPS in clinical behavior, pathology, and molecular markers, these TLS-positive LMS tumors may overlap with this LMS subtype, which requires further validation.4.2. PD-L1

PD-L1 expression is a controversial biomarker of response across tumor types, as its prognostic and predictive value is often imperfect, depends on the type of ICB used, and the method of evaluation of the biomarker. Early studies exploring PD-L1 expression in LMS were limited by small cohorts and inconsistent protein expression. D’Angelo et al. used IHC to stain for both tumor cell– and macrophage-associated PD-L1 expression in a cohort of LMS samples. The authors identified macrophage-associated PD-L1 expression in 25% of LMS samples; however, the sample size was small, and the authors were unable to identify tumor PD-L1 expression [99][137]. Similarly, other studies have found PD-L1 protein expression to be around 30%, with significantly higher proportion of PD-L1 positive in high-grade LMS compared with low grade LMS, indicating once again that higher grade, more dedifferentiated LMS may have a more inflammatory, immune infiltrated tumor microenvironment [100][138]. Another study by Kim et al., on the other hand, identified PD-L1 expression in 70% of the LMS samples by IHC. However, the authors noted that there was a tendency toward a higher tumor stage among LMS patients; as such, the increase in PD-L1 expression may reflect more advanced tumor biology as a result of more severe disease [101][139].4.3. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes

Beyond B cells and TLS, the presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) has gained increasing interest because of its association with the presence of immune-checkpoint markers. In particular, TILs have been associated with TIM-3 and LAG-3, both of which contribute to T-cell exhaustion and may facilitate resistance to anti-PD1/PDL1 [102][103][141,142]. Dancsok et al. examined TIL profiles among a large cohort of patients with STS. When categorizing STS according to karyotype, the authors observed that complex-karyotype tumors, including LMS, contained a significantly higher density of TILs than simple-karyotype or chromosomal translocation-associated sarcomas [104][143]. LMS was specifically characterized by higher densities of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, CD4+ helper T cells, FOXP3+ T-regulatory cells, and natural killer cells. Despite these findings, intratumoral expression of PD-L1 was infrequent, as the authors observed PD-L1 staining by IHC in 22% of samples. However, a higher TIL score was not correlated with the expression of other immune-checkpoint markers, as the authors observed 58% and 74% of the LMS samples expressing LAG-3 and TIM-3, respectively. In addition, a higher density of TILs was associated with improved OS and PFS in complex-karyotype tumors.45.4. Macrophages

There is an increasing body of evidence suggesting that macrophages play a significant role in the development and progression of epithelial malignancies [105][106]. Macrophages are often recruited to sites of disease and contribute to progression of cancer through the release of growth factors and cytokines that ultimately support angiogenesis [107]. The presence of TAMs has thus been associated with a worse prognosis in various cancer histologies, including kidney, bladder, esophageal, and breast cancer [108][109][110][111]. Initial studies to characterize the immune microenvironment in LMS have corroborated these findings; dense infiltration of CD68+ TAMs and CD163+ TAMs was identified in 26% and 44% of LMS samples, respectively. Notably, both the presence and density of TAMs were associated with a worse prognosis in both uLMS and ST-LMS [112]. On Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, there was significantly improved OS in both uLMS and ST-LMS samples with sparse density of CD68+ and CD163+ TAMs, with an estimated 5-year disease-specific survival of 100% in sparse CD163+ ST-LMS compared to 40% and 70% in dense and moderate CD163+ ST-LMS tumors, respectively.There is an increasing body of evidence suggesting that macrophages play a significant role in the development and progression of epithelial malignancies [170, 171]. Macrophages are often recruited to sites of disease and contribute to progression of cancer through the release of growth factors and cytokines that ultimately support angiogenesis [172]. The presence of TAMs has thus been associated with a worse prognosis in various cancer histologies, including kidney, bladder, esophageal, and breast cancer [173-176]. Initial studies to characterize the immune microenvironment in LMS have corroborated these findings; dense infiltration of CD68+ TAMs and CD163+ TAMs was identified in 26% and 44% of LMS samples, respectively. Notably, both the presence and density of TAMs were associated with a worse prognosis in both uLMS and ST-LMS [177]. On Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, there was significantly improved OS in both uLMS and ST-LMS samples with sparse density of CD68+ and CD163+ TAMs, with an estimated 5-year disease-specific survival of 100% in sparse CD163+ ST-LMS compared to 40% and 70% in dense and moderate CD163+ ST-LMS tumors, respectively.

Checkpoint-associated proteins may modulate the behavior of TAMs and play an important role in immunologic evasion. In particular, CD47 has gained interest because of its frequent expression in several sarcoma histologic subtypes. CD47 is a transmembrane protein that interacts with SIRPα expressed on macrophages and dendritic cells to prevent phagocytosis [113]. Among STS, CD47 expression appears bimodal, with the highest protein expression level observed in chordoma, angiosarcoma, and pleomorphic liposarcoma; CD47-expressing tumors are associated with worse OS than are CD47-negative tumors [114]. Anti-CD47 therapy has yielded promising results in early-phase clinical trials among patients with both solid and liquid tumors [115][116], and in vitro experimentation suggests that anti-CD47 therapy induces the expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL2, TNFα, and IFNγ in STS [117]. As such, anti-CD47 therapy may represent a promising therapeutic option for LMS patients, particularly given the macrophage-rich tumor microenvironment, and warrants further investigation.Checkpoint-associated proteins may modulate the behavior of TAMs and play an important role in immunologic evasion. In particular, CD47 has gained interest because of its frequent expression in several sarcoma histologic subtypes. CD47 is a transmembrane protein that interacts with SIRPα expressed on macrophages and dendritic cells to prevent phagocytosis [178]. Among STS, CD47 expression appears bimodal, with the highest protein expression level observed in chordoma, angiosarcoma, and pleomorphic liposarcoma; CD47-expressing tumors are associated with worse OS than are CD47-negative tumors [179]. Anti-CD47 therapy has yielded promising results in early-phase clinical trials among patients with both solid and liquid tumors [180, 181], and in vitro experimentation suggests that anti-CD47 therapy induces the expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL2, TNFα, and IFNγ in STS [182]. As such, anti-CD47 therapy may represent a promising therapeutic option for LMS patients, particularly given the macrophage-rich tumor microenvironment, and warrants further investigation.