Precision and organization govern the cell cycle, ensuring normal proliferation. However, some cells may undergo abnormal cell divisions (neosis) or variations of mitotic cycles (endopolyploidy). Consequently, the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs), critical for tumor survival, resistance, and immortalization, can occur. Newly formed cells end up accessing numerous multicellular and unicellular programs that enable metastasis, drug resistance, tumor recurrence, and self-renewal or diverse clone formation. An integrative literature review was carried out, searching articles in several sites, including: PUBMED, NCBI-PMC, and Google Academic, published in English, indexed in referenced databases and without a publication time filter, but prioritizing articles from the last 3 years, to answer the following questions: (i) “What is the current knowledge about polyploidy in tumors?”; (ii) “What are the applications of computational studies for the understanding of cancer polyploidy?”; and (iii) “How do PGCCs contribute to tumorigenesis?”

- polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs)

- tumor ecology

- tumor evolution

- heterogeneity

- entropy

- self-organization

- bioinformatics

- system biology

1. Polyploidy in Cancer

2. Polyploid Giant Cancer Cells (PGCCs)

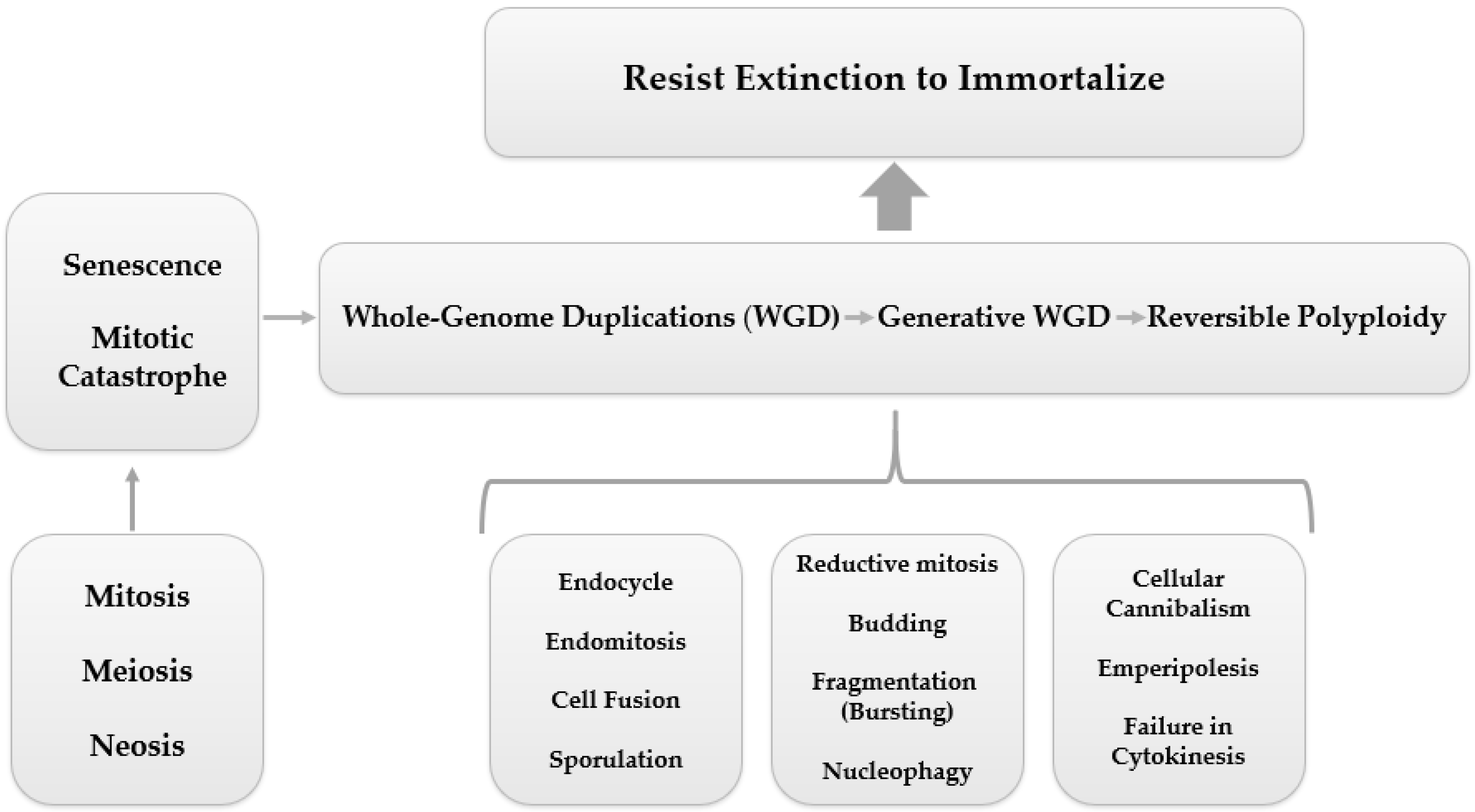

2.1. PGCC’s Giant Cell Cycle

Giant Cell Cycle Possible Outcomes and Fates

2.2. PGCCs Functionalities: Plasticity, Metabolism and Resistance to Therapy

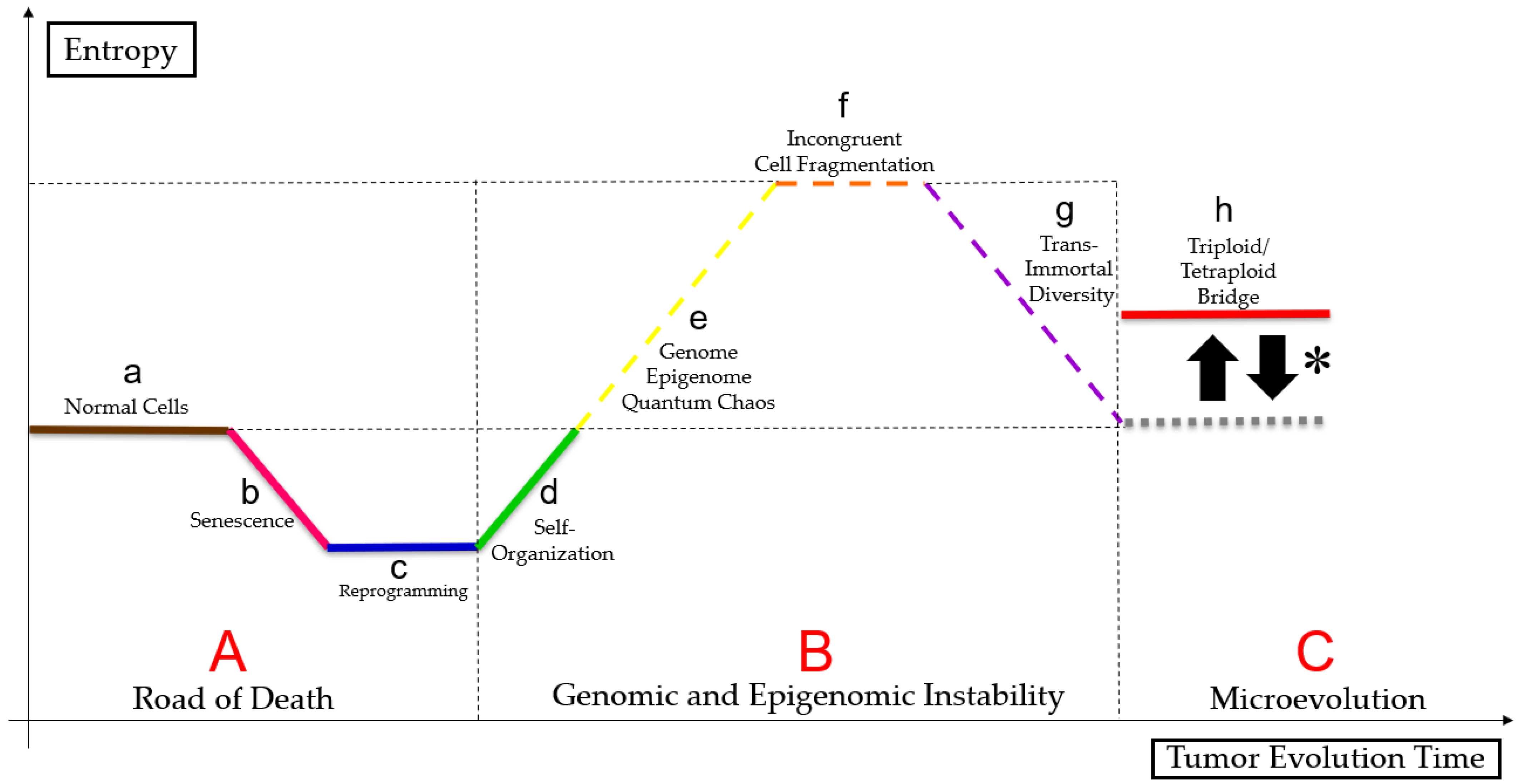

2.3. PGCC’s Role in Tumor Evolution

2.4. Genome Chaos

2.5. PGCCs Characterization in Diverse Cancer Types

2.5.1. Breast and Ovarian Cancer

2.5.2. Colorectal Cancer

2.5.3. Glioblastoma

2.5.4. Lung Cancer

2.5.5. Prostate Cancer and Melanoma

2.5.6. Only Ovarian Cancer

2.5.7. Only Breast Cancer

2.6. Autophagy, Senescence and PGCCs

3. Reaching New Paths

References

- Shu, Z.; Row, S.; Deng, W.-M. Endoreplication: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 465–474.

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S. Asymmetric cell division in polyploid giant cancer cells and low eukaryotic cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 432652.

- Liu, J. The dualistic origin of human tumors. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 53, pp. 1–16.

- Anatskaya, O.V.; Vinogradov, A.E. Polyploidy as a Fundamental Phenomenon in Evolution, Development, Adaptation and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3542.

- Archetti, M. Polyploidy as an Adaptation against Loss of Heterozygosity in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8528.

- Wu, C.S.; Lu, W.H.; Hung, M.C.; Huang, Y.S.; Chao, H.W. From polyploidy to polyploidy reversal: Its role in normal and disease states. Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 991–995.

- Bukkuri, A.; Pienta, K.J.; Austin, R.H.; Hammarlund, E.U.; Amend, S.R.; Brown, J.S. A life history model of the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of polyaneuploid cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13713.

- Anatskaya, O.V.; Vinogradov, A.E. Whole-Genome Duplications in Evolution, Ontogeny, and Pathology: Complexity and Emergency Reserves. Mol. Biol. 2021, 55, 813–827.

- Lukow, D.A.; Sheltzer, J.M. Chromosomal instability and aneuploidy as causes of cancer drug resistance. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 43–53.

- Mukherjee, S.; Ali, A.M.; Murty, V.V.; Raza, A. Mutation in SF3B1 gene promotes formation of polyploid giant cells in Leukemia cells. Med. Oncol. 2022, 39, 65.

- Kasperski, A. Life Entrapped in a Network of Atavistic Attractors: How to Find a Rescue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4017.

- Niculescu, V.F. Cancer genes and cancer stem cells in tumorigenesis: Evolutionary deep homology and controversies. Genes Dis. 2022, 9, 1234–1247.

- Amend, S.R.; Torga, G.; Lin, K.C.; Kostecka, L.G.; de Marzo, A.; Austin, R.H.; Pienta, K.J. Polyploid giant cancer cells: Unrecognized actuators of tumorigenesis, metastasis, and resistance. Prostate 2019, 79, 1489–1497.

- White-Gilbertson, S.; Voelkel-Johnson, C. Giants and monsters: Unexpected characters in the story of cancer recurrence. Adv. Cancer Res. 2020, 148, 201–232.

- Alameddine, R.S.; Hamieh, L.; Shamseddine, A. From sprouting angiogenesis to erythrocytes generation by cancer stem cells: Evolving concepts in tumor microcirculation. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 986768.

- Yang, Z.; Yao, H.; Fei, F.; Li, Y.; Qu, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, S. Generation of erythroid cells from polyploid giant cancer cells: Re-thinking about tumor blood supply. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 144, 617–627.

- Niu, N.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, N.; Mercado-Uribe, I.; Tao, F.; Han, Z.; Pathak, S.; Multani, A.S.; Kuang, J.; Yao, J.; et al. Linking genomic reorganization to tumor initiation via the giant cell cycle. Oncogenesis 2016, 5, e281.

- Liu, J. The “life code”: A theory that unifies the human life cycle and the origin of human tumors. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 60, pp. 380–397.

- Amend, S.R.; Pienta, K.J. Ecology meets cancer biology: The cancer swamp promotes the lethal cancer phenotype. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 9669.

- Liu, J.; Niu, N.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Sood, A.K. The life cycle of polyploid giant cancer cell and dormancy in cancer: Opportunities for novel therapeutic interventions. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 81, pp. 132–144.

- Liu, J.; Erenpreisa, J.; Sikora, E. Polyploid giant cancer cells: An emerging new field of cancer biology. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 81, pp. 1–4.

- Liu, J. Giant cells: Linking McClintock’s heredity to early embryogenesis and tumor origin throughout millennia of evolution on Earth. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 81, pp. 176–192.

- Song, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, Z.; Zhao, R.; Huang, Q. Stress-Induced Polyploid Giant Cancer Cells: Unique Way of Formation and Non-Negligible Characteristics. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 3390.

- Erenpreisa, J.; Salmina, K.; Anatskaya, O.; Cragg, M.S. Paradoxes of cancer: Survival at the brink. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 81, pp. 119–131.

- Niu, N.; Mercado-Uribe, I.; Liu, J. Dedifferentiation into blastomere-like cancer stem cells via formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. Oncogene 2017, 36, 4887–4900.

- Erenpreisa, J.; Cragg, M.S. Three steps to the immortality of cancer cells: Senescence, polyploidy and self-renewal. Cancer Cell Int. 2013, 13, 92.

- Erenpreisa, J.; Salmina, K.; Anatskaya, O.; Vinogradov, A.; Cragg, M.S. The Enigma of cancer resistance to treatment. Organisms. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 5, 71–75.

- Mayfield-Jones, D.; Washburn, J.D.; Arias, T.; Edger, P.P.; Pires, J.C.; Conant, G.C. Watching the grin fade: Tracing the effects of polyploidy on different evolutionary time scales. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 24, pp. 320–331.

- Moein, S.; Adibi, R.; Meirelles, L.d.S.; Nardi, N.B.; Gheisari, Y. Cancer regeneration: Polyploid cells are the key drivers of tumor progression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 2020, 1874, 188408.

- Dasari, K.; Somarelli, J.A.; Kumar, S.; Townsend, J.P. The somatic molecular evolution of cancer: Mutation, selection, and epistasis. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2021, 165, 56–65.

- Somarelli, J.A.; Gardner, H.; Cannataro, V.L.; Gunady, E.F.; Boddy, A.M.; Johnson, N.A.; Fisk, J.N.; Gaffney, S.G.; Chuang, J.H.; Li, S.; et al. Molecular biology and evolution of cancer: From discovery to action. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 320–326.

- Dujon, A.M.; Aktipis, A.; Alix-Panabières, C.; Amend, S.R.; Boddy, A.M.; Brown, J.S.; Capp, J.P.; DeGregori, J.; Ewald, P.; Gatenby, R.; et al. Identifying key questions in the ecology and evolution of cancer. Evol. Appl. 2021, 14, 877–892.

- Casás-Selves, M.; DeGregori, J. How cancer shapes evolution and how evolution shapes cancer. Evol. Educ. Outreach 2011, 4, 624–634.

- Fortunato, A.; Boddy, A.; Mallo, D.; Aktipis, A.; Maley, C.C.; Pepper, J.W. Natural selection in cancer biology: From molecular snowflakes to trait hallmarks. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7, a029652.

- Arendt, D. The evolution of cell types in animals: Emerging principles from molecular studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 868–882.

- Arendt, D.; Musser, J.M.; Baker, C.V.; Bergman, A.; Cepko, C.; Erwin, D.H.; Wagner, G.P. The origin and evolution of cell types. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 744–757.

- Tarashansky, A.J.; Musser, J.M.; Khariton, M.; Li, P.; Arendt, D.; Quake, S.R.; Wang, B. Mapping single-cell atlases throughout Metazoa unravels cell type evolution. eLife 2021, 10, e66747.

- Was, H.; Borkowska, A.; Olszewska, A.; Klemba, A.; Marciniak, M.; Synowiec, A.; Kieda, C. Polyploidy formation in cancer cells: How a Trojan horse is born. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Volume 81, pp. 24–36.

- Niculescu, V.F. aCLS cancers: Genomic and epigenetic changes transform the cell of origin of cancer into a tumorigenic pathogen of unicellular organization and lifestyle. Gene 2020, 726, 144174.

- Niculescu, V.F. Is an ancient genome repair mechanism the Trojan Horse of cancer. Nov Appro Can Study 2021, 5, 555–557.

- Baker, S.G.; Kramer, B.S. Paradoxes in carcinogenesis: New opportunities for research directions. BMC Cancer 2007, 7, 151.

- Baker, S.G. Paradoxes in carcinogenesis should spur new avenues of research: An historical perspective. Disruptive Sci. Technol. 2012, 1, 100–107.

- Heng, J.; Heng, H.H. Two-phased evolution: Genome chaos-mediated information creation and maintenance. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2021, 165, 29–42.

- Heng, J.; Heng, H.H. Genome chaos: Creating new genomic information essential for cancer macroevolution. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 81, pp. 160–175.

- Heng, J.; Heng, H.H. Genome Chaos, Information Creation, and Cancer Emergence: Searching for New Frameworks on the 50th Anniversary of the “War on Cancer”. Genes 2021, 13, 101.

- Liu, J.; Mercado-Uribe, I.; Niu, N.; Sun, B.; Kuang, J.; Zhang, S. Re-thinking the concept of cancer stem cells: Polyploid giant cancer cells as mother cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1917.

- Baramiya, M.G.; Baranov, E. From cancer to rejuvenation: Incomplete regeneration as the missing link (Part I: The same origin, different outcomes). Future Sci. AO 2020, 6, FSO450.

- Baramiya, M.G.; Baranov, E.; Saburina, I.; Salnikov, L. From cancer to rejuvenation: Incomplete regeneration as the missing link (part II: Rejuvenation circle). Future Sci. AO 2020, 6, FSO610.

- Lin, K.C.; Torga, G.; Sun, Y.; Axelrod, R.; Pienta, K.J.; Sturm, J.C.; Austin, R.H. The role of heterogeneous environment and docetaxel gradient in the emergence of polyploid, mesenchymal and resistant prostate cancer cells. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2019, 36, 97–108.

- Liu, K.; Zheng, M.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Fu, F.; Zhang, H.; Du, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Different p53 genotypes regulating different phosphorylation sites and subcellular location of CDC25C associated with the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 83.

- Wang, X.; Zheng, M.; Fei, F.; Li, C.; Du, J.; Liu, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. EMT-related protein expression in polyploid giant cancer cells and their daughter cells with different passages after triptolide treatment. Med. Oncol. 2019, 36, 82.

- Lopez-Sanchez, L.M.; Jimenez, C.; Valverde, A.; Hernandez, V.; Penarando, J.; Martinez, A.; Lopez-Pedrera, C.; Muñoz-Castañeda, J.R.; Haba-Rodríguez, J.R.D.; Aranda, E.; et al. CoCl2, a mimic of hypoxia, induces formation of polyploid giant cells with stem characteristics in colon cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99143.

- Zhang, D.; Yang, X.; Yang, Z.; Fei, F.; Li, S.; Qu, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S. Daughter cells and erythroid cells budding from PGCCs and their clinicopathological significances in colorectal cancer. J. Cancer 2017, 8, 469.

- Fei, F.; Li, C.; Cao, Y.; Liu, K.; Du, J.; Gu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. CK7 expression associates with the location, differentiation, lymph node metastasis, and the Dukes’ stage of primary colorectal cancers. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 2510.

- Fei, F.; Zhang, M.; Li, B.; Zhao, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Ding, P.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Formation of polyploid giant cancer cells involves in the prognostic value of neoadjuvant chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 2316436.

- Fei, F.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Du, J.; Liu, K.; Li, B.; Yao, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Syncytin 1, CD9, and CD47 regulating cell fusion to form PGCCs associated with cAMP/PKA and JNK signaling pathway. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 3047–3058.

- Fei, F.; Qu, J.; Liu, K.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. The subcellular location of cyclin B1 and CDC25 associated with the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells and their clinicopathological significance. Lab. Investig. 2019, 99, 483–498.

- Fei, F.; Liu, K.; Li, C.; Du, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. Molecular mechanisms by which S100A4 regulates the migration and invasion of PGCCs with their daughter cells in human colorectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 182.

- Qu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Rong, Z.; He, T.; Zhang, S. Number of glioma polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs) associated with vasculogenic mimicry formation and tumor grade in human glioma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 32, 75.

- Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wu, M.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Xu, C.; Chen, L. Hypoxia-induced polypoid giant cancer cells in glioma promote the transformation of tumor-associated macrophages to a tumor-supportive phenotype. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2022, 28, 1326–1338.

- Tagal, V.; Roth, M.G. Loss of Aurora kinase signaling allows lung cancer cells to adopt endoreplication and form polyploid giant cancer cells that resist antimitotic drugs. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 400–413.

- Glassmann, A.; Garcia, C.C.; Janzen, V.; Kraus, D.; Veit, N.; Winter, J.; Probstmeier, R. Staurosporine induces the generation of polyploid giant cancer cells in non-small-cell lung carcinoma A549 cells. Anal. Cell. Pathol. 2018, 2018, 7.

- White-Gilbertson, S.; Lu, P.; Jones, C.M.; Chiodini, S.; Hurley, D.; Das, A.; Delaney, J.R.; Norris, J.S.; Voelkel-Johnson, C. Tamoxifen is a candidate first-in-class inhibitor of acid ceramidase that reduces amitotic division in polyploid giant cancer cells—Unrecognized players in tumorigenesis. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 3142–3152.

- White-Gilbertson, S.; Lu, P.; Esobi, I.; Echesabal-Chen, J.; Mulholland, P.J.; Gooz, M.; Ogretmen, B.; Stamatikos, A.; Voelkel-Johnson, C. Polyploid giant cancer cells are dependent on cholesterol for progeny formation through amitotic division. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8971.

- Zhang, S.; Mercado-Uribe, I.; Hanash, S.; Liu, J. iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis of polyploid giant cancer cells and budding progeny cells reveals several distinct pathways for ovarian cancer development. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80120.

- Lv, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.; Liu, G.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Fei, F.; Zhang, S. Polyploid giant cancer cells with budding and the expression of cyclin E, S-phase kinase-associated protein 2, stathmin associated with the grading and metastasis in serous ovarian tumor. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 576.

- Zhang, S.; Mercado-Uribe, I.; Xing, Z.; Sun, B.; Kuang, J.; Liu, J. of cancer stem-like cells through the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. Oncogene 2014, 33, 116–128.

- Zhang, L.; Ding, P.; Lv, H.; Zhang, D.; Liu, G.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S. Number of polyploid giant cancer cells and expression of EZH2 are associated with VM formation and tumor grade in human ovarian tumor. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 903542.

- Liu, K.; Lu, R.; Zhao, Q.; Du, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, S. Association and clinicopathologic significance of p38MAPK-ERK-JNK-CDC25C with polyploid giant cancer cell formation. Med. Oncol. 2020, 37, 6.

- Zhang, S.; Mercado-Uribe, I.; Liu, J. Tumor stroma and differentiated cancer cells can be originated directly from polyploid giant cancer cells induced by paclitaxel. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 508–518.

- Fei, F.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, S. The number of polyploid giant cancer cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related proteins are associated with invasion and metastasis in human breast cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 34, 158.

- Sirois, I.; Aguilar-Mahecha, A.; Lafleur, J.; Fowler, E.; Vu, V.; Scriver, M.; Buchanan, M.; Chabot, C.; Ramanathan, A.; Balachandran, B.; et al. A unique morphological phenotype in chemoresistant triple-negative breast cancer reveals metabolic reprogramming and PLIN4 expression as a molecular vulnerability. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17, 2492–2507.

- You, B.; Xia, T.; Gu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, J.; Fan, Y.; Yao, H.; Pan, S.; Lu, Y.; et al. AMPK–mTOR–Mediated Activation of Autophagy Promotes Formation of Dormant Polyploid Giant Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 846–858.

- Bowers, R.R.; Andrade, M.F.; Jones, C.M.; White-Gilbertson, S.; Voelkel-Johnson, C.; Delaney, J.R. Autophagy modulating therapeutics inhibit ovarian cancer colony generation by polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs). BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 410.

- Czarnecka-Herok, J.; Sliwinska, M.A.; Herok, M.; Targonska, A.; Strzeszewska-Potyrala, A.; Bojko, A.; Wolny, A.; Mosieniak, G.; Sikora, E. Therapy-Induced Senescent/Polyploid Cancer Cells Undergo Atypical Divisions Associated with Altered Expression of Meiosis, Spermatogenesis and EMT Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8288.

- Ye, J.C.; Horne, S.; Zhang, J.Z.; Jackson, L.; Heng, H.H. Therapy induced genome chaos: A novel mechanism of rapid cancer drug resistance. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 676344.

- Paul, D. The systemic hallmarks of cancer. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2020, 6, 29.

- Zhang, J.; Qiao, Q.; Xu, H.; Zhou, R.; Liu, X. Human cell polyploidization: The good and the evil. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 81, pp. 54–63.

- Zhang, S.; Xu, X.; Zhu, S.; Liu, J. PGCCS generating erythrocytes to form VM structure contributes to tumor blood supply. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 402619.

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, X. Tumor budding, micropapillary pattern, and polyploidy giant cancer cells in colorectal cancer: Current status and future prospects. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 4810734.

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, X.; Deng, Z.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Y.; He, S.; Huang, Q. Irradiation-induced polyploid giant cancer cells are involved in tumor cell repopulation via neosis. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 2219–2234.

- Liu, H.T.; Xia, T.; You, Y.W.; Zhang, Q.C.; Ni, H.S.; Liu, Y.F.; Liu, Y.R.; Xu, Y.Q.; You, B.; Zhang, Z.X. Characteristics and clinical significance of polyploid giant cancer cells in laryngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2021, 6, 1228–1234.

- Liu, L.L.; Long, Z.J.; Wang, L.X.; Zheng, F.M.; Fang, Z.G.; Yan, M.; Xu, D.F.; Chen, J.J.; Wang, S.W.; Lin, D.J.; et al. Inhibition of mTOR Pathway Sensitizes Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells to Aurora Inhibitors by Suppression of Glycolytic Metabolism. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013, 11, 1326–1336.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of cancer: New dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46.

- Nam, A.S.; Chaligne, R.; Landau, D.A. Integrating genetic and non-genetic determinants of cancer evolution by single-cell multi-omics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021, 22, 3–18.

- Hasanzad, M.; Sarhangi, N.; Ehsani Chimeh, S.; Ayati, N.; Afzali, M.; Khatami, F.; Nikfar, S.; Aghaei Meybodi, H.R. Precision medicine journey through omics approach. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2021, 21, 881–888.

- Lewis, S.M.; Asselin-Labat, M.L.; Nguyen, Q.; Berthelet, J.; Tan, X.; Wimmer, V.C.; Merino, D.; Rogers, K.L.; Naik, S.H. Spatial omics and multiplexed imaging to explore cancer biology. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 997–1012.

- Dotolo, S.; Esposito, A.R.; Roma, C.; Guido, D.; Preziosi, A.; Tropea, B.; Palluzzi, F.; Giacò, L.; Normanno, N. Bioinformatics: From NGS Data to Biological Complexity in Variant Detection and Oncological Clinical Practice. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2074.

- Jiang, P.; Sinha, S.; Aldape, K.; Hannenhalli, S.; Sahinalp, C.; Ruppin, E. Big data in basic and translational cancer research. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 625–639.