1. Polyploidy in Cancer

Cell cycle deregulation and/or failures in mitosis can lead to polyploidy, the upregulation of genes that positively impact the cell cycle progression, and cytostatic genes downregulation

[1][2][27,28] in physiological and pathological manners

[3][29]. Polyploidy, or whole genome duplication (WGDs), results from the cell cycle prematurely ending or from cellular fusion

[4][30], increasing genetic variation, stress tolerance, the ability to colonize different environments, and mutation burden relief. The evolutionary selective advantages of WGD offer a theoretical base for cyclic ploidy, mitotic slippage, and cancer cell fusion

[5][31].

Polyploid cells are vulnerable during meiosis due to chromosome pairing difficulties and genomic instability

[4][30]; this can be solved by a transient reversion of polyploidy (depolyploidization)

[6][32], multipolar division

[7][33], chromosomal rearrangement, and DNA divergence. A high degree of polyploidy or aneuploidy are detrimental to the cell, but can increase cellular adaptability and plasticity, fueling intratumoral heterogeneity

[8][9][34,35].

2. Polyploid Giant Cancer Cells (PGCCs)

PGCCs have been observed for at least 180 years in diverse cancer types

[10][11][12][13][36,37,38,39]. Some were observed after chemotherapy, in cells with irregular nuclei, increased migratory potential, genetic instability, altered response to hypoxia, drug resistance, or higher mortality rates

[14][40].

PGCCs are a special subpopulation of tumor cells containing a large cytoplasm and multiple nuclei

[15][41], undergoing an altered giant cell cycle, creating genetic heterogeneity, and allowing cancer cells to overcome multiple micro-environment challenges

[16][42].

2.1. PGCC’s Giant Cell Cycle

Stress factors such as chemotherapy, antimitotic drugs, radiotherapy, hypoxia, or a deficient microenvironment may induce PGCCs formation

[2][28] by means of a giant cell cycle (cycle linked to polyploidization and depolyploidization processes together with neosis) used for dedifferentiation of somatic cells, which can generate stem cells for tumor initiation. Such a cell cycle is divided in four phases: (i) Initiation: stressed tumor cells undergo catastrophic mitosis or cell death. Surviving cells assume a tetraploid or polyploid transient state

[17][18][1,11]; (ii) Auto-renovation: tetraploid cells start endocycling to produce mononuclear or multinuclear PGCCs. Some multinuclear cells go through cyto-fission to create smaller polyploid cells

[17][18][1,11]; (iii) Termination: PGCCs undergo depolyploidization (genome reduction division) and generate diploid nuclei by budding. Others form a structure that resembles a reproductive cyst

[17][18][1,11]; and (iv) Stability: diploid descendent cells with altered genotypes continue to differentiate into a variety of aneuploid cell types with proliferative capacity

[17][18][1,11].

Giant Cell Cycle Possible Outcomes and Fates

There is a correlation between endoreplication cell cycles and the amount of DNA replication mistakes, followed by complete dedifferentiation. In parallel, cell division stagnation reflects the degree of tumor malignancy

[18][11]. As a result of polyploidization, cancer cells can: (i) initiate metastasis; (ii) survive “lethal” drugs; or (iii) divide asymmetrically to generate cell multilineages with higher therapy resistance

[13][19][39,43]. The giant cell cycle can lead to tumor evolution, numbness, resistance, recurrence, and regeneration, as shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Giant cell cycle outcomes. Under stress, the cell responds in various ways to maintain balance. When chemotherapy treated tumor cells are isolated, large numbers of cells die; surviving cells may start an altered cell cycle, capable of generating PGCCs, which follow four phases or other unusual divisions; PGCCs exhibit abnormal shapes similar to single-celled organisms such as amoebas, or embryonic cells at the blastomere stage; that (A) can undergo diapause, dormancy, relapse, and generate multilineages; (B) tumor cells use these means to survive and generate resistant daughter cells by budding, fragmentation (bursting), sporulation or encystment; (C) new genetic and epigenetic characteristics create unlimited potential for more aggressive, resistant and immortal phenotypes. Note: created with

BioRender.com (accessed on 15 March 2023).

Genotoxic agents used in cancer therapy are associated with the induction of cell stress, ploidy, and cell size variation; these can lead to the generation of 3D structures similar to a blastocyst

[20][21][44,45]. These blastocyst-like multicellular structures with a reprogrammed genome can generate resistant daughter-cells of different lineages that can acquire the capacity to go through embryonic latency, a reversible state of numbness, to survive environmental stress factors

[20][22][44,46].

PGCCs can rejuvenate by way of amitotic division, generating cancer stem cells like blastomeres, that may transdifferentiate into different lineages, while the mother cell retains undifferentiated cancer properties

[21][45].

2.2. PGCCs Functionalities: Plasticity, Metabolism and Resistance to Therapy

The diversity of PGCCs functions suggests polyploidy as an evolutionary source of tissue regeneration and plasticity, being explored by cancer cells to promote survival

[23][47] and stress response

[3][24][29,48], recap embryonic stages

[25][49], exhibit adaptive exploration of multiple gene regulatory networks

[24][26][48,50], and regulate biochemical and biophysical pathways

[27][28][51,52].

The Warburg effect is the utilization of aerobic glycolysis for ATP synthesis, despite having abundant oxygen available. PGCCs probably use a Warburg effect similar to the embryo in state of pre-implantation by means of glucose repression of oxidative phosphorylation, as seen in the yeast Crabtree effect. The occurrence of polyploidy or aneuploidy in PGCCs ends up passing through gene losses that could alter the relative amount of enzymes favoring glycolysis, and, consequently, investing in rapid cell division

[23][28][47,52].

The functionalities developed by the PGCCs also influence tumor resistance and recurrence; these are still big challenges for modern therapies, especially because they can produce stem cells able to repopulate the tumor microenvironment

[29][53].

Thus, polyploid tumor cells can be used as a molecular model for better understanding fundamental evolutive paradigms

[30][31][54,55]; evolution studies may help us answer questions about cancer resistance and success

[32][56].

2.3. PGCC’s Role in Tumor Evolution

Tumor evolution is a process by which tumor cells change across time, acquiring advantageous characteristics for their survival and perpetuation, surviving immune attack, drug treatments, and diverse anti-proliferative signals

[33][34][57,58]. Key mechanisms and processes altered from tumor initiation to progression include proliferation, motility, metabolism, autocrine signaling, activated intracellular pathways, inflammation, plasticity, senescence, transdifferentiation, and cell cannibalism

[34][58].

PGCCs also share features of the Mendel and McClintock models

[22][46], showing independent segregation for different characteristics. Stressed cells respond by redefining their genomic structure to promote tumor success

[22][46], primarily because PGCCs exhibit diverse gene expression, which leads to neosis

[24][48]. The stress previously suffered directs tumor cells to certain paths, including apoptosis, necrosis, senescence, mitotic catastrophe, or a mixture of these processes

[24][48]. However, when the tumor overcomes the death threshold through alterations in regulatory networks

[35][36][37][59,60,61], polyploidization becomes possible in a generative and reversible process

[24][48].

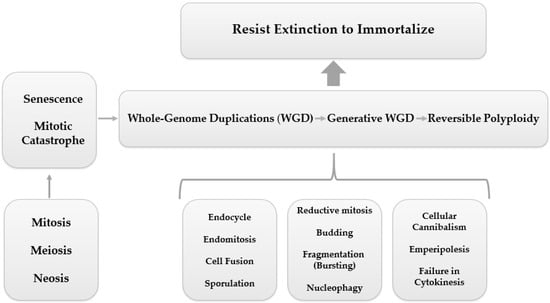

In parallel to this mechanism of ploidy regulation, numerous other processes are shared by PGCCs, including endoreplication (endocycle and endomitosis), cell fusion, cytokinesis failure, cell cannibalism (entosis), emperipolesis, reductive mitosis, budding, fragmentation, nucleophagy, and sporulation (asexual reproduction), leading to a quite unlimited potential for PGCCs to resist extinction and achieve immortalization

[24][38][48,62], as shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2. PGCC mediated tumor evolution. Cell division errors, such as mitotic arrest, can cause whole-genome duplications (WGD), which is represented by a reversible polyploidy, originated from biological processes such as endocycling, endomitosis, cell fusion, cellular cannibalism, emperipolesis, cytokinesis failure, reductive mitosis, budding, fragmentation (bursting), nucleophagy, and sporulation. Reversible polyploidy may create resistance to tumor extinction.

Vladimir Niculescu has also highlighted the potential of “pre-existing PGCCs” (before response to therapies) that can turn into multinucleated genome repair structures (MGRNs) and, subsequently, originate PGCCs

[12][39][40][38,63,64].

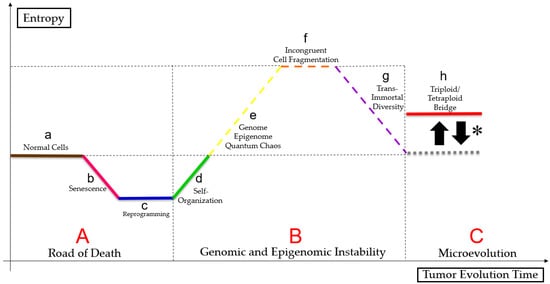

2.4. Genome Chaos

Liu

[3][29] suggests that cell size regulation may control micro- and macroevolution, as somatic cells can follow the Waddington epigenetic landscape. PGCCs can overcome stress signals by rapidly adapting, living close to the genome, epigenome, and quantum chaos, altering cell fates, reprogramming, phylogenetically regressing, and senescing

[24][41][42][48,65,66]. Therefore, that clonal selection enables better-adapted tumor cell survival, as shown in the

Figure 3 (figure based on a bibliographic compilation by Erenpreisa and Cragg

[27][51], Erenpreisa et al.

[28][52], Heng and Heng

[43][67], Heng and Heng

[44][68], Heng and Heng

[45][69], Liu et al.

[46][70], Baramiya and Baranov

[47][71] and Baramiya et al.

[48][72]).

Figure 3. Paradoxical cancer life cycle. Normal cells (a) follow a linear ontogenetic process towards cell death interspersed with senescence (b), in a pathway called “road of death” (A). Some tumor cells may undergo reprogramming (c) and self-organization (d) either by mitotic catastrophe or by neosis or by mitotic slippage, because of genome, epigenome and quantum chaos (e), resulting in changes in cell fate. Tumor undergoes a macroevolutionary process (genomic and epigenomic instability (B)). Polyploid tumor cells undergo epigenetic and genetic regression, causing incongruent cell fragmentation (f), to achieve trans-immortal diversity (access to immortalization capacity, resistance to extinction and heterogeneous profile in the formation of multilineages of more apt tumor aneuploid cells) (g) new tumor cells follow a Darwinian evolution (microevolution (C)) and maintain a “triploid/tetraploid bridge” (*), between states 2n and pn–“triploid/tetraploid bridge” (h).

2.5. PGCCs Characterization in Diverse Cancer Types

Experimental studies with tumor cell lines suggest that targeted PGCCs therapies in cancer may be more efficient than conventional therapies. Even under similar stresses, PGCCs may exhibit tumor specific features and responses, which are shown below according to tumor type:

2.5.1. Breast and Ovarian Cancer

Lin et al.

[49][23] showed that chemotherapy-originated PGCCs upregulated the expression of Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) gene, correlating with metastases. Liu et al.

[50][73] and Wang et al.

[51][74], researching PGCCs in breast and ovarian cancer cell lines, identified a relationship between metastasis from resistant PGCCs offspring and higher lymph node grades, as well as an association between asymmetric divisions and tumor resistance.

2.5.2. Colorectal Cancer

Lopez-Sánchez et al.

[52][75], Zhang et al.

[53][21], Fei et al.

[54][15], Fei et al.

[55][76], Fei et al.

[56][77], Fei et al.

[57][78], and Fei et al.

[58][6] highlighted that, in colorectal cancer cell lines, PGCCs were associated with overexpression of HIF-1α, CK7, cathepsin B, E-cadherin, fibronectin, Snail, Slug, Twist-1, Syncytin 1, CD9, CD47, JNK1, cyclin B1, S100A4, and downregulation of CDC25A, CDC25B, and CDC25C, affecting cell cycle regulation, vasculogenic mimicry, migration, and invasion.

2.5.3. Glioblastoma

Qu et al.

[59][7] and Liu et al.

[60][79], studying glioblastoma cell lines, observed a relationship between PGCCs’ number and higher tumor grade, hypoxia, red cytoplasmic inclusions, budding vasculogenic mimicry, tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment, and more aggressive phenotypes.

2.5.4. Lung Cancer

Tagal and Roth

[61][14] and Glassmann et al.

[62][5] showed an association between staurosporine generated PGCCs and polyploid and multinucleated growth traits in lung cancer cell lines.

2.5.5. Prostate Cancer and Melanoma

White-Gilbertson et al.

[63][64][25,80], working with prostate cancer and melanoma cell lines, found that ASAH1 inhibition and cholesterol regulation are associated with PGCCs generation, being a bridge to tumor survival.

2.5.6. Only Ovarian Cancer

Zhang et al.

[65][81], Lv et al.

[66][82], Zhang et al.

[67][83], Zhang et al.

[68][84], Niu et al.

[17][1], Niu, Mercado-Uribe, and Liu

[25][49], and Liu et al.

[69][85] revealed associations between PGCCs and cell cycle, motility, metabolism, vasculogenic mimetism, auto-renovation, nuclear fragmentation, and tumor aggressiveness using ovarian cancer cell lines.

2.5.7. Only Breast Cancer

Zhang, Mercado-Uribe, and Liu

[70][13], Fei et al.

[71][3], and Sirois et al.

[72][24], studying breast cancer cell lines, suggested that PGCCs offspring can form organotypic structures in vitro, stromal transdifferentiation, chemoresistant cells, higher migratory capacity, and metabolic reprogramming.

Ultimately, the primary purposes of tumor polyploidization are to activate survival and aggressiveness (metastasis).

2.6. Autophagy, Senescence and PGCCs

Autophagy seems to be involved in the generation of PGCCs, since autophagy inhibitors before chemotherapy decreases the formation of PGCCs

[73][86]. This process modulates PGCCs colony formation by stoppage, representing paradoxical roles both beneficial and harmful to PGCCs.

Senescence and PGCCs have been related through comparative transcriptome studies, revealing the altered expression of meiotic cell cycle genes, spermatogenesis, and EMT

[74][75][87,88]. Senescence induced by chemotherapy can halter tumor proliferation, but this response also causes polyploidization, leading to PGCCs formation

[76][77][89,90].

Cellular damage triggered by genotoxic stress induces senescence which, under the influence of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) and immune response evasion, facilitates reversible polyploidy through mitotic slippage, circumventing mitotic catastrophe and terminal senescence, followed by endoreplication and damage repair; this, in turn, directs new polyploid tumor cells to generate aneuploid offspring

[21][26][45,50]. There mechanisms are still little understood, but they result in more aggressive tumor profiles

[78][79][91,92].

3. Reaching New Paths

Histological, physiological, and morphological PGCCs studies used (i) CoCl

2 and traditional cancer treatments for PGCCs induction

[52][78][75,91]; (ii) classic tumor cell lineages

[79][80][92,93]; (iii) PGCCs generated by budding

[81][82][94,95]; and (iv) protein expression studies

[83][96], showing that PGCCs’ acquired features are similar to classic tumor marks, described by Hanahan and Weinberg

[84][97], Hanahan and Weinberg

[85][98], and Hanahan

[86][99], contributing to needed cancer traits for utter success

[80][93].

The complexity of PGCCs motivated recent computational approaches, providing new insights into essential questions about such cells. Single cell

[87][100], multi-omics (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, electroma)

[88][89][101,102], bioinformatics, NGS

[90][103], Big Data, and Artificial Intelligence

[91][104], together with laboratory studies, have provided a better interpretation of polyploidy, elucidating its multiple cellular states

[87][100], epigenetic and genetic profiles

[88][101], spatial distributions

[89][102], microenvironmental interactions

[90][103], and translational advances

[90][91][103,104].