Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Beatrix Zheng and Version 1 by An-Shan Hsiao.

Microtubules (MTs) are essential elements of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton and are critical for various cell functions. During cell division, plant MTs form highly ordered structures, and cortical MTs guide the cell wall cellulose patterns and thus control cell size and shape. Both are important for morphological development and for adjusting plant growth and plasticity under environmental challenges for stress adaptation. Various MT regulators control the dynamics and organization of MTs in diverse cellular processes and response to developmental and environmental cues.

- microtubules

- microtubule-associated proteins

- development

1. Introduction

Microtubules (MTs) are highly conserved cytoskeletal structures in both plant and mammal cells [1,2][1][2]. Like mammal MTs, plant MTs consist of α- and β-tubulin subunits [3[3][4],4], and some tubulin isoforms are expressed in specialized cells or tissues during development [5,6,7,8][5][6][7][8]. The formation of α/β-tubulin heterodimers needs a large chaperone complex and guanosine 5′-triphosphate (GTP) [9,10][9][10]. Hence, recombinant tubulins cannot be efficiently produced in Escherichia coli because of the lack of a proper protein folding machinery in prokaryotes [11]. The longitudinal head-to-tail interactions between α/β-tubulin heterodimers via GTP hydrolysis to guanosine diphosphate build up the basic units of MTs, protofilaments [12,13][12][13]. The GTP cap at the plus end ensures MT growth, while the loss of the GTP cap results in MT shrinkage. The co-existence of growing and shrinking MTs driven by the restoration and hydrolysis of GTP was proposed as a “dynamic instability” model based on the observation of in vitro-reconstituted MTs [14]. The dynamic behaviour of MTs is thought to be an intrinsic property, as demonstrated by a MT polymerization experiment conducted from purified tubulin without external factors [15].

MT polymerization can occur spontaneously in vitro without any pre-formed templates when sufficiently high concentrations of purified tubulins are warmed up in the presence of GTP [16]. However, in cells, tubulin molecules tend to form a nucleation seed for efficiently initiating polymer growth and the construction of dynamic polar MTs under spatial and temporal control [17,18][17][18]. The evolutionarily conserved MT nucleating template is known as the γ-tubulin-containing ring complex (γ-TuRC) [19,20,21][19][20][21]. It initiates MT nucleation at a particular subcellular location, primarily regulated by Augmin [22,23,24][22][23][24]. Katanin internally breaks MTs dependent on adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), particularly at MT crossover positions, where the detached daughter MTs can translocate via treadmilling to form new configurations of MT arrays [25,26,27,28,29][25][26][27][28][29]. Thus, both γ-TuRC and katanin are thought to be central components in synthesizing new treadmilling MTs at the plant cell cortex [25,30][25][30]. The dynamic nature enables MTs to alter their organization in response to internal and external signals for the needs of the cell, and it is regulated by various proteins [31,32][31][32].

Eukaryotes have conserved MT-associated proteins (MAPs) that bind along the MT lattice and have stabilizing or destabilizing effects on MT assembly [32,33,34][32][33][34]. However, plants possess a set of MAPs specific to plant morphology and physiology [35,36,37][35][36][37]. Conventional MAPs include motor proteins such as kinesins that utilize MTs as tracks to transport cargo and structural MAPs or severing proteins such as MAP65 and katanin (with the catalytic subunit p60 and a regulatory subunit p80) involved in MT organization via binding, bundling, or cleavage of MTs. MTs plus tip-associated proteins, such as cytoplasmic linker-associated proteins (CLASPs), regulate MT dynamics via their binding and interactions at the plus-end of growing MTs [13,36,38,39,40,41,42,43][13][36][38][39][40][41][42][43].

MTs arise from centrosomes in animal cells [44], but MTs in acentrosomal plant cells are thought to self-organize into structured arrays [45]. The plant-specific structures (i.e., cell wall and stomata) and the sessile nature of land plants lead to distinct MT regulation, affecting plant growth, development, and stress adaptation.

2. MTs in Plant Cell Division

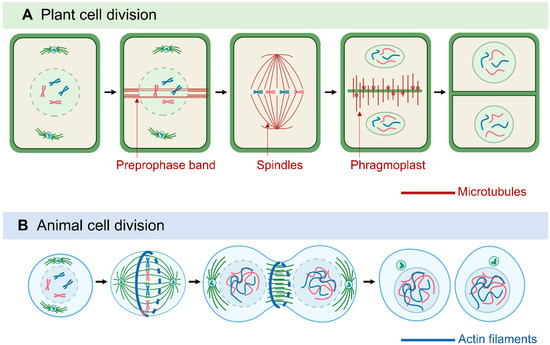

Sessile plants cannot move as quickly as multicellular animals to escape environmental challenges. Thus, besides forming organs and various cell types for morphological development, cell division in plants is also important for adaptation to environmental conditions: adjusting growth under stress by enhancing, reducing, and redirecting cell growth [46]. In dividing plant cells, MTs form distinct structures, including the preprophase band (PPB), the acentrosomal mitotic spindle, and the phragmoplast [47,48,49][47][48][49] (Figure 1). The PPB, which is a plant-specific cortical MT ring, marks the orientation of the cell division plane and determines the spindle positioning in metaphase [50,51,52][50][51][52]. The PPB tunes the orientation of spindles in a mode similar to that of centrioles and astral MTs in animal cells, which implies the importance of spindle orientation [51,53][51][53].

Figure 1. Comparison of plant and animal cell division. Plant cell division (A) is characterized by microtubule (MT)-based structures: the preprophase band, the acentrosomal mitotic spindle, and the phragmoplast. In animal cell cytokinesis (B), the contractile ring pinches the cell into two daughter cells, whereas plant phragmoplasts extend and guide vesicle fusion to generate the cell plate.

MT-based spindles separate chromosomes during mitosis [54]. Most animal spindle-assembly factors are well conserved in plants, but plants lack two major elements: centrosomal components and the cytoplasmic dynein complex [48]. Animal spindle MTs nucleate from centrosomes [55], whereas plant MTs appear to nucleate from the nuclear envelope surface [56]. In animals and fungi, cytoplasmic dynein is a processive minus-end-directed motor that pulls on astral MTs from the cell cortex for efficient and accurate spindle assembly and positioning [57]. In contrast, plants lack cytoplasmic dynein but contain many minus-end–directed kinesin-14 proteins, which were thought to be involved in the sliding of anti-parallel microtubules throughout mitosis [46,58,59,60][46][58][59][60]. Kinesins with a calponin homology domain (KCH) are a distinguished subclass of kinesin-14 found only in Plantae [61]. Rice OsKCH2 exhibits processive minus-end-directed motility on MTs to potentially compensate for the loss of dynein [62], whereas moss KCH drives MT-based nuclear transport reminiscent of animal dynein [63]. In animals, plus-end–directed kinesin-5 and kinesin-12 facilitate the spindle arrangement [64,65][64][65] and it seems to be conserved in plants, as shown by Arabidopsis KINESIN-12E controlling spindle MT organization and size during mitosis [66]. MTs are protein–protein interaction sites for the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) protein complex and signaling network. Plants have conserved the SAC network with some variations from animals and yeast [67]. The dissection of proteins associated with SAC led to the discovery of novel aspects of plant SAC regulation [68[68][69],69], which may be relevant for plant breeding studies because ploidy alternations likely rely on SAC properties.

Another plant-specific MT machinery, the phragmoplast, is formed between the reconstituting daughter nuclei at the end of telophase, as a hallmark of cytokinesis [70]. The phragmoplast expands and transports Golgi-derived vesicles containing building materials to facilitate the construction of the cell plate. The assembly, crosslinking, and turnover of phragmoplast MTs are regulated by various MAPs, kinesin motors, and regulatory enzymes [49,53,70,71,72][49][53][70][71][72]. Among them, plant-specific Cortical MT Disordering 4 tethers the conserved MT-severing protein katanin to facilitate phragmoplast expansion and accelerate cytokinesis [73]. Cytokinesis-specific MAP65-3 plays primary roles in phragmoplast integrity and efficient cell plate formation [74,75,76][74][75][76]. Phragmoplast dynamics during cytokinesis is closely related to the phosphorylation of MAP65-3, regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 and aurora kinase [77,78,79][77][78][79]. As a positive regulation mechanism, benzimidazole-3 proteins interact with MAP65-3 and promote MT bundling for phragmoplast expansion [80]. The MT motor protein KINESIN12 is critical for maintaining MT plus-ends in the phragmoplast midzone. Indeed, the Arabidopsis double-mutant pok1/pok2 (two kinesin-12 orthologs) revealed chaotic division sites and a slower phragmoplast expansion rate compared to the wild-type [81,82][81][82]. Overall, because they lack structurally defined centrosomes but have flexible and distributed PPB and phragmoplasts, plant cells can assemble bipolar spindles and determine the division plane with a great deal of plasticity, thereby compensating for the restraints in cell movement caused by the stiff plant cell wall [46,83].

[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83].

References

- Paluh, J.L.; Killilea, A.N.; Detrich, H.W. 3rd; Downing, K.H. Meiosis-specific failure of cell cycle progression in fission yeast by mutation of a conserved beta-tubulin residue. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 1160-1171.Paluh, J.L.; Killilea, A.N.; Detrich, H.W., 3rd; Downing, K.H. Meiosis-specific failure of cell cycle progression in fission yeast by mutation of a conserved beta-tubulin residue. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 1160–1171.

- Rayevsky, A.V.; Sharifi, M.; Samofalova, D.A.; Karpov, P.A.; Blume, Y.B. Structural and functional features of lysine acetylation of plant and animal tubulins. Cell Biol. Int. 2019, 43, 1040-1048.Rayevsky, A.V.; Sharifi, M.; Samofalova, D.A.; Karpov, P.A.; Blume, Y.B. Structural and functional features of lysine acetylation of plant and animal tubulins. Cell Biol. Int. 2019, 43, 1040–1048.

- Mohri, H. Amino-acid composition of “Tubulin” constituting microtubules of sperm flagella. Nature 1968, 217, 1053–1054.Mohri, H. Amino-acid composition of “Tubulin” constituting microtubules of sperm flagella. Nature 1968, 217, 1053–1054.

- Little, M.; Seehaus, T. Comparative analysis of tubulin sequences. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 1988, 90, 655–670.Little, M.; Seehaus, T. Comparative analysis of tubulin sequences. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 1988, 90, 655–670.

- Kopczak, S.D.; Haas, N.A.; Hussey, P.J.; Silflow, C.D.; Snustad, D.P. The small genome of Arabidopsis contains at least six expressed -tubulin genes. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 539–547.Kopczak, S.D.; Haas, N.A.; Hussey, P.J.; Silflow, C.D.; Snustad, D.P. The small genome of Arabidopsis contains at least six expressed α-tubulin genes. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 539–547.

- Snustad, D.P.; Haas, N.A.; Kopczak, S.D.; Silflow, C.D. The small genome of Arabidopsis contains at least nine expressed -tubulin genes. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 549–556.Snustad, D.P.; Haas, N.A.; Kopczak, S.D.; Silflow, C.D. The small genome of Arabidopsis contains at least nine expressed β-tubulin genes. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 549–556.

- Breviario, D.; Giani, S.; Morello, L. Multiple tubulins: evolutionary aspects and biological implications. Plant J. 2013, 75, 202-221.Breviario, D.; Giani, S.; Morello, L. Multiple tubulins: Evolutionary aspects and biological implications. Plant J. 2013, 75, 202–221.

- Hashimoto, T. Dissecting the cellular functions of plant microtubules using mutant tubulins. Cytoskeleton 2013, 70, 191-200.Hashimoto, T. Dissecting the cellular functions of plant microtubules using mutant tubulins. Cytoskeleton 2013, 70, 191–200.

- Steinborn, K.; Maulbetsch, C.; Priester, B.; Trautmann, S.; Pacher, T.; Geiges, B.; Küttner, F.; Lepiniec, L.; Stierhof, Y.D., Schwarz, H. et al. The Arabidopsis PILZ group genes encode tubulin-folding cofactor orthologs required for cell division but not cell growth. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 959–971Steinborn, K.; Maulbetsch, C.; Priester, B.; Trautmann, S.; Pacher, T.; Geiges, B.; Küttner, F.; Lepiniec, L.; Stierhof, Y.D.; Schwarz, H.; et al. The Arabidopsis PILZ group genes encode tubulin-folding cofactor orthologs required for cell division but not cell growth. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 959–971.

- Szymanski, D. Tubulin folding cofactors: half a dozen for a dimer. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, R767–R769.Szymanski, D. Tubulin folding cofactors: Half a dozen for a dimer. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, R767–R769.

- Lewis, S.A.; Tian, G.; Cowan, N.J. The - and -tubulin folding pathways. Trends Cell Biol. 1997, 7, 479-485.Lewis, S.A.; Tian, G.; Cowan, N.J. The α- and β-tubulin folding pathways. Trends Cell Biol. 1997, 7, 479–485.

- Müller-Reichert, T.; Chrétien, D.; Severin, F.; Hyman, A.A. Structural changes at microtubule ends accompanying GTP hydrolysis: information from a slowly hydrolyzable analogue of GTP, guanylyl (alpha,beta)methylenediphosphonate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1998, 95, 3661-3666.Müller-Reichert, T.; Chrétien, D.; Severin, F.; Hyman, A.A. Structural changes at microtubule ends accompanying GTP hydrolysis: Information from a slowly hydrolyzable analogue of GTP, guanylyl (alpha, beta)methylenediphosphonate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 3661–3666.

- Hashimoto, T. Microtubules in plants. Arabidopsis Book 2015, 13, e0179.Hashimoto, T. Microtubules in plants. Arab. Book 2015, 13, e0179.

- Mitchison, T., Kirschner, M. Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature 1984, 312, 237–242.Mitchison, T.; Kirschner, M. Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature 1984, 312, 237–242.

- Cassimeris, L. Regulation of microtubule dynamic instability. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton.Cassimeris, L. Regulation of microtubule dynamic instability. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 1993, 26, 275–281.

- Carlier, M.F.; Pantaloni, D. Kinetic analysis of cooperativity in tubulin polymerization in the presence of guanosine di- or triphosphate nucleotides. Biochemistry 1978, 17, 1908–1915Carlier, M.F.; Pantaloni, D. Kinetic analysis of cooperativity in tubulin polymerization in the presence of guanosine di- or triphosphate nucleotides. Biochemistry 1978, 17, 1908–1915.

- Job, D.; Valiron, O.; Oakley, B. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003, 15, 111-117.Job, D.; Valiron, O.; Oakley, B. Microtubule nucleation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003, 15, 111–117.

- Hashimoto, T. A ring for all: g-tubulin-containing nucleation complexes in acentrosomal plant microtubule arrays. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013, 16, 698-703.Hashimoto, T. A ring for all: G-tubulin-containing nucleation complexes in acentrosomal plant microtubule arrays. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013, 16, 698–703.

- Teixido-Travesa, N.; Roig, J.; Luders, J. The where, when and how of microtubule nucleation — one ring to rule them all. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 4445–4456.Teixido-Travesa, N.; Roig, J.; Luders, J. The where, when and how of microtubule nucleation—One ring to rule them all. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 4445–4456.

- Lin, T. C.; Neuner, A.; Schiebel, E. Targeting of γ-tubulin complexes to microtubule organizing centers: conservation and divergence. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 296–307.Lin, T.C.; Neuner, A.; Schiebel, E. Targeting of γ-tubulin complexes to microtubule organizing centers: Conservation and divergence. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 296–307.

- Roostalu, J., Surrey, T. Microtubule nucleation: beyond the template. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 702-710.Roostalu, J.; Surrey, T. Microtubule nucleation: Beyond the template. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 702–710.

- Kollman, J.M.; Polka, J.K.; Zelter, A.; Davis, T.N.; Agard, D.A. Microtubule nucleating gamma-TuSC assembles structures with 13-fold microtubule-like symmetry. Nature 2010, 466, 879-882.Kollman, J.M.; Polka, J.K.; Zelter, A.; Davis, T.N.; Agard, D.A. Microtubule nucleating gamma-TuSC assembles structures with 13-fold microtubule-like symmetry. Nature 2010, 466, 879–882.

- Ho, C.-M.K.; Hotta, T.; Kong, Z.; Zeng, C.J.T.; Sun. J.; Lee, Y.-R.J.; Liu, B. Augmin plays a critical role in organizing the spindle and phragmoplast microtubule arrays in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 2606-2618.Ho, C.-M.K.; Hotta, T.; Kong, Z.; Zeng, C.J.T.; Sun, J.; Lee, Y.-R.J.; Liu, B. Augmin plays a critical role in organizing the spindle and phragmoplast microtubule arrays in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 2606–2618.

- Nakaoka, Y.; Miki, T.; Fujioka, R.; Uehara, R.; Tomioka, A.; Obuse, C.; Kubo, M.; Hiwatashi, Y.; Goshima, G. An inducible RNA interference system in Physcomitrella patens reveals a dominant role of augmin in phragmoplast microtubule generation. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 1478-1493.Nakaoka, Y.; Miki, T.; Fujioka, R.; Uehara, R.; Tomioka, A.; Obuse, C.; Kubo, M.; Hiwatashi, Y.; Goshima, G. An inducible RNA interference system in Physcomitrella patens reveals a dominant role of augmin in phragmoplast microtubule generation. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 1478–1493.

- Nakamura, M.; Ehrhardt, D.W.; Hashimoto, T. Microtubule and katanin-dependent dynamics of microtubule nucleation complexes in the acentrosomal Arabidopsis cortical array. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 1064 – 1070.Nakamura, M.; Ehrhardt, D.W.; Hashimoto, T. Microtubule and katanin-dependent dynamics of microtubule nucleation complexes in the acentrosomal Arabidopsis cortical array. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 1064–1070.

- Lindeboom, J.J.; Nakamura, M.; Hibbel, A.; Shundyak, K.; Gutierrez, R.; Ketelaar, T.; Emons, A.M.; Mulder, B.M.; Kirik, V.; Ehrhardt, D.W. A mechanism for reorientation of cortical microtubule arrays driven by microtubule severing. Science 2013, 342, 1245533.Lindeboom, J.J.; Nakamura, M.; Hibbel, A.; Shundyak, K.; Gutierrez, R.; Ketelaar, T.; Emons, A.M.; Mulder, B.M.; Kirik, V.; Ehrhardt, D.W. A mechanism for reorientation of cortical microtubule arrays driven by microtubule severing. Science 2013, 342, 1245533.

- Wightman, R.; Chomicki, G.; Kumar, M.; Carr, P.; Turner, S.R. SPIRAL2 determines plant microtubule organization by modulating microtubule severing. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 1902–1907.Wightman, R.; Chomicki, G.; Kumar, M.; Carr, P.; Turner, S.R. SPIRAL2 determines plant microtubule organization by modulating microtubule severing. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 1902–1907.

- Zhang, Q.; Fishel, E.; Bertroche, T.; Dixit, R. Microtubule severing at crossover sites by katanin generates ordered cortical microtubule arrays in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 2191–2195.Zhang, Q.; Fishel, E.; Bertroche, T.; Dixit, R. Microtubule severing at crossover sites by katanin generates ordered cortical microtubule arrays in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 2191–2195.

- Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Dong, L.; Han, L.; Wang, Q.; Tian, J.; Yu, Y.; Gao, C.; Kong, Z. KTN80 confers precision to microtubule severing by specific targeting of katanin complexes in plant cells. EMBO. J. 2017, 36, 3435-3447.Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Dong, L.; Han, L.; Wang, Q.; Tian, J.; Yu, Y.; Gao, C.; et al. KTN80 confers precision to microtubule severing by specific targeting of katanin complexes in plant cells. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 3435–3447.

- Ehrhardt, D. W.; Shaw, S. L. Microtubule dynamics and organization of the plant cortical array. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 859–875.Ehrhardt, D.W.; Shaw, S.L. Microtubule dynamics and organization of the plant cortical array. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 859–875.

- Horio, T.; Murata, T. The role of dynamic instability in microtubule organization. Front.Horio, T.; Murata, T. The role of dynamic instability in microtubule organization. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 511.

- Goodson, H.V.; Jonasson, E.M. Microtubules and Microtubule-Associated Proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 2018, 10, a022608.Goodson, H.V.; Jonasson, E.M. Microtubules and Microtubule-Associated Proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a022608.

- Bodakuntla, S.; Jijumon, A.S.; Villablanca, C.; Gonzalez-Billault, C.; Janke, C. Microtubule-Associated Proteins: Structuring the Cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 804-819.Bodakuntla, S.; Jijumon, A.S.; Villablanca, C.; Gonzalez-Billault, C.; Janke, C. Microtubule-Associated Proteins: Structuring the Cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 804–819.

- Gottschalk, A.C.; Hefti, M.M. The evolution of microtubule associated proteins - a reference proteomic perspective. BMC Genomics. 2022, 23, 266.Gottschalk, A.C.; Hefti, M.M. The evolution of microtubule associated proteins—A reference proteomic perspective. BMC Genomics. 2022, 23, 266.

- Buschmann, H.; Lloyd, C.W. Arabidopsis mutants and the network of microtubule-associated functions. Mol. Plant 2008, 1, 888-898.Buschmann, H.; Lloyd, C.W. Arabidopsis mutants and the network of microtubule-associated functions. Mol. Plant 2008, 1, 888–898.

- Gardiner, J. The evolution and diversification of plant microtubule associated proteins. Plant J. 2013, 75, 219-229.Gardiner, J. The evolution and diversification of plant microtubule associated proteins. Plant J. 2013, 75, 219–229.

- Elliott, A.; Shaw, S.L. Update: Plant cortical microtubule arrays. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 94-105.Elliott, A.; Shaw, S.L. Update: Plant cortical microtubule arrays. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 94–105.

- Lloyd, C.; Hussey, P. Microtubule-associated proteins in plants - why we need a map. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 40–47.Lloyd, C.; Hussey, P. Microtubule-associated proteins in plants—Why we need a map. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 40–47.

- Akhmanova, A.; Steinmetz, M. O. Tracking the ends: a dynamic protein network controls the fate of microtubule tips. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 309–322.Akhmanova, A.; Steinmetz, M.O. Tracking the ends: A dynamic protein network controls the fate of microtubule tips. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 309–322.

- Sedbrook, J. C.; Kaloriti, D. Microtubules, MAPs and plant directional cell expansion. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 303–310.Sedbrook, J.C.; Kaloriti, D. Microtubules, MAPs and plant directional cell expansion. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 303–310.

- Hamada, T. Microtubule organization and microtubule-associated proteins in plant cells. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 312, 1–52.Hamada, T. Microtubule organization and microtubule-associated proteins in plant cells. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 312, 1–52.

- Li, S.; Sun, T.; Ren, H. The functions of the cytoskeleton and associated proteins during mitosis and cytokinesis in plant cells. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 282.Li, S.; Sun, T.; Ren, H. The functions of the cytoskeleton and associated proteins during mitosis and cytokinesis in plant cells. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 282.

- Krtková, J.; Benáková, M.; Schwarzerová, K. Multifunctional microtubule-associated proteins in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 474.Krtková, J.; Benáková, M.; Schwarzerová, K. Multifunctional microtubule-associated proteins in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 474.

- Desai, A.; Mitchison, T.J. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997, 13, 83-117.Desai, A.; Mitchison, T.J. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997, 13, 83–117.

- Dixit, R.; Cyr, R. The cortical microtubule array: from dynamics to organization. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2546–2552.Dixit, R.; Cyr, R. The cortical microtubule array: From dynamics to organization. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2546–2552.

- Motta, M.R.; Schnittger, A. A microtubule perspective on plant cell division. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R547-R552.Motta, M.R.; Schnittger, A. A microtubule perspective on plant cell division. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R547–R552.

- Pickett-Heaps, J. D.; Northcote, D. H. Organization of microtubules and endoplasmic reticulum during mitosis and cytokinesis in wheat meristems. J. Cell Sci. 1966, 1, 109–120.Pickett-Heaps, J.D.; Northcote, D.H. Organization of microtubules and endoplasmic reticulum during mitosis and cytokinesis in wheat meristems. J. Cell Sci. 1966, 1, 109–120.

- Yamada, M.; Goshima, G. Mitotic spindle assembly in land plants: molecules and mechanisms. Biology (Basel) 2017, 6, 6,Yamada, M.; Goshima, G. Mitotic spindle assembly in land plants: Molecules and mechanisms. Biology 2017, 6, 6.

- Smertenko, A. Phragmoplast expansion: the four-stroke engine that powers plant cytokinesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 46, 130–137.Smertenko, A. Phragmoplast expansion: The four-stroke engine that powers plant cytokinesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 46, 130–137.

- Marcus, A. I.; Dixit, R.; Cyr, R. J. Narrowing of the preprophase microtubule band is not required for cell division plane determination in cultured plant cells. Protoplasma 2005, 226, 169–174.Marcus, A.I.; Dixit, R.; Cyr, R.J. Narrowing of the preprophase microtubule band is not required for cell division plane determination in cultured plant cells. Protoplasma 2005, 226, 169–174.

- Schaefer, E.; Belcram, K.; Uyttewaal, M.; Duroc, Y.; Goussot, M.; Legland, D., Laruelle, E.; de Tauzia-Moreau, M.L.; Pastuglia, M.; Bouchez, D. The preprophase band of microtubules controls the robustness of division orientation in plants. Science 2017, 356, 186–189.Schaefer, E.; Belcram, K.; Uyttewaal, M.; Duroc, Y.; Goussot, M.; Legland, D.; Laruelle, E.; de Tauzia-Moreau, M.L.; Pastuglia, M.; Bouchez, D. The preprophase band of microtubules controls the robustness of division orientation in plants. Science 2017, 356, 186–189.

- Vavrdová, T.; ˇSamaj, J.; Komis, G. Phosphorylation of plant microtubule-associated proteins during cell division. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 238.Vavrdová, T.; Samaj, J.; Komis, G. Phosphorylation of plant microtubule-associated proteins during cell division. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 238.

- Livanos, P.; Müller, S. Division plane establishment and cytokinesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 239-267.Livanos, P.; Müller, S. Division plane establishment and cytokinesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 239–267.

- Gadde, S.; Heald, R. Mechanisms and molecules of the mitotic spindle. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, R797-805.Gadde, S.; Heald, R. Mechanisms and molecules of the mitotic spindle. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, R797–R805.

- Conduit, P.T.; Richens, J.H.; Wainman, A.; Holder, J.; Vicente, C.C.; Pratt, M.B.; Dix, C.I.; Novak, Z.A.; Dobbie, I.M.; Schermelleh, L.; et al. A molecular mechanism of mitotic centrosome assembly in drosophila. eLife 2014, 3, e03399.Conduit, P.T.; Richens, J.H.; Wainman, A.; Holder, J.; Vicente, C.C.; Pratt, M.B.; Dix, C.I.; Novak, Z.A.; Dobbie, I.M.; Schermelleh, L.; et al. A molecular mechanism of mitotic centrosome assembly in drosophila. eLife 2014, 3, e03399.

- Bannigan, A.; Lizotte-Waniewski, M.; Riley, M.; Baskin, T.I. Emerging molecular mechanisms that power and regulate the anastral mitotic spindle of flowering pants. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 2008, 65, 1–11.Bannigan, A.; Lizotte-Waniewski, M.; Riley, M.; Baskin, T.I. Emerging molecular mechanisms that power and regulate the anastral mitotic spindle of flowering pants. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 2008, 65, 1–11.

- Gassmann, R. Dynein at the kinetochore. J. Cell Sci. 2023, 136, jcs220269.Gassmann, R. Dynein at the kinetochore. J. Cell Sci. 2023, 136, jcs220269.

- Reddy, A.S.; Day, I.S. Kinesins in the Arabidopsis genome: a comparative analysis among eukaryotes. BMC Genomics. 2001, 2, 2.Reddy, A.S.; Day, I.S. Kinesins in the Arabidopsis genome: A comparative analysis among eukaryotes. BMC Genomics. 2001, 2, 2.

- Guo, L.; Ho, C.M.; Kong, Z.; Lee, Y.R.; Qian, Q.; Liu, B. Evaluating the microtubule cytoskeleton and its interacting proteins in monocots by mining the rice genome. Ann Bot. 2009, 103, 387-402.Guo, L.; Ho, C.M.; Kong, Z.; Lee, Y.R.; Qian, Q.; Liu, B. Evaluating the microtubule cytoskeleton and its interacting proteins in monocots by mining the rice genome. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 387–402.

- Lucas, J.; Geisler, M. Sequential loss of dynein sequences precedes complete loss in land plants. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 1237-1240.Lucas, J.; Geisler, M. Sequential loss of dynein sequences precedes complete loss in land plants. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 1237–1240.

- Lee, Y.R.; Liu, B. Cytoskeletal motors in Arabidopsis. Sixty-one kinesins and seventeen myosins. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 3877-3883.Lee, Y.R.; Liu, B. Cytoskeletal motors in Arabidopsis. Sixty-one kinesins and seventeen myosins. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 3877–3883.

- Tseng, K.F.; Wang, P.; Lee, Y.J.; Bowen, J.; Gicking, A.M.; Guo, L.; Liu, B.; Qiu, W. The preprophase band-associated kinesin-14 OsKCH2 is a processive minus-end-directed microtubule motor. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1067.Tseng, K.F.; Wang, P.; Lee, Y.J.; Bowen, J.; Gicking, A.M.; Guo, L.; Liu, B.; Qiu, W. The preprophase band-associated kinesin-14 OsKCH2 is a processive minus-end-directed microtubule motor. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1067.

- Yamada, M.; Goshima, G. The KCH kinesin drives nuclear transport and cytoskeletal coalescence to promote tip cell growth in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 1496-1510.Yamada, M.; Goshima, G. The KCH kinesin drives nuclear transport and cytoskeletal coalescence to promote tip cell growth in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 1496–1510.

- Ferenz, N.P.; Gable, A.; Wadsworth, P. Mitotic functions of kinesin-5. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010, 21, 255-259.Ferenz, N.P.; Gable, A.; Wadsworth, P. Mitotic functions of kinesin-5. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010, 21, 255–259.

- Hancock, W.O. Mitotic kinesins: a reason to delve into kinesin-12. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R968-970.Hancock, W.O. Mitotic kinesins: A reason to delve into kinesin-12. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R968–R970.

- Herrmann, A.; Livanos, P.; Zimmermann, S.; Berendzen, K.; Rohr, L.; Lipka, E.; Müller, S. KINESIN-12E regulates metaphase spindle flux and helps control spindle size in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 27-43.Herrmann, A.; Livanos, P.; Zimmermann, S.; Berendzen, K.; Rohr, L.; Lipka, E.; Müller, S. KINESIN-12E regulates metaphase spindle flux and helps control spindle size in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 27–43.

- Komaki, S.; Schnittger, A. The spindle checkpoint in plants-a green variation over a conserved theme? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2016, 34, 84-91.Komaki, S.; Schnittger, A. The spindle checkpoint in plants-a green variation over a conserved theme? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2016, 34, 84–91.

- Komaki, S.; Schnittger, A. The spindle assembly checkpoint in Arabidopsis is rapidly shut off during severe stress. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 172-185.Komaki, S.; Schnittger, A. The spindle assembly checkpoint in Arabidopsis is rapidly shut off during severe stress. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 172–185.

- Su, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Feng, C.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, J.; Birchler, J.A.; Han, F. Knl1 participates in spindle assembly checkpoint signaling in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2021, 118, e2022357118.Su, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Feng, C.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, J.; Birchler, J.A.; Han, F. Knl1 participates in spindle assembly checkpoint signaling in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022357118.

- Smertenko, A.; Hewitt, S.L.; Jacques, C.N.; Kacprzyk, R.; Liu, Y.; Marcec, M.J.; Moyo, L.; Ogden, A.; Oung, H.M.; Schmidt, S.; Serrano-Romero, E.A. Phragmoplast microtubule dynamics - a game of zones. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, jcs203331.Smertenko, A.; Hewitt, S.L.; Jacques, C.N.; Kacprzyk, R.; Liu, Y.; Marcec, M.J.; Moyo, L.; Ogden, A.; Oung, H.M.; Schmidt, S.; et al. Phragmoplast microtubule dynamics—A game of zones. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, jcs203331.

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Lei, P.; Zhang, H.; Yu, F. MOR1/MAP215 acts synergistically with katanin to control cell division and anisotropic cell elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3006-3027.Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Lei, P.; Zhang, H.; Yu, F. MOR1/MAP215 acts synergistically with katanin to control cell division and anisotropic cell elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3006–3027.

- Mills, A.M.; Morris, V.H.; Rasmussen, C.G. The localization of PHRAGMOPLAST ORIENTING KINESIN1 at the division site depends on the microtubule-binding proteins TANGLED1 and AUXIN-INDUCED IN ROOT CULTURES9 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 4583-4599.Mills, A.M.; Morris, V.H.; Rasmussen, C.G. The localization of PHRAGMOPLAST ORIENTING KINESIN1 at the division site depends on the microtubule-binding proteins TANGLED1 and AUXIN-INDUCED IN ROOT CULTURES9 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 4583–4599.

- Sasaki, T.; Tsutsumi, M.; Otomo, K.; Murata, T.; Yagi, N.; Nakamura, M.; Nemoto, T.; Hasebe, M.; Oda, Y. A novel katanin-tethering machinery accelerates cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 4060–4070.Sasaki, T.; Tsutsumi, M.; Otomo, K.; Murata, T.; Yagi, N.; Nakamura, M.; Nemoto, T.; Hasebe, M.; Oda, Y. A novel katanin-tethering machinery accelerates cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 4060–4070.

- Ho, C.M.; Hotta, T.; Guo, F.; Roberson, R.W.; Lee, Y.R.; Liu, B. Interaction of antiparallel microtubules in the phragmoplast is mediated by the microtubule-associated protein MAP65-3 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 2909–2923.Ho, C.M.; Hotta, T.; Guo, F.; Roberson, R.W.; Lee, Y.R.; Liu, B. Interaction of antiparallel microtubules in the phragmoplast is mediated by the microtubule-associated protein MAP65-3 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 2909–2923.

- Ho, C.M.; Lee, Y.R.; Kiyama, L.D.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P.; Liu, B. Arabidopsis microtubule-associated protein MAP65-3 cross-links antiparallel microtubules toward their plus ends in the phragmoplast via its distinct c-terminal microtubule binding domain. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2071–2085.Ho, C.M.; Lee, Y.R.; Kiyama, L.D.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P.; Liu, B. Arabidopsis microtubule-associated protein MAP65-3 cross-links antiparallel microtubules toward their plus ends in the phragmoplast via its distinct c-terminal microtubule binding domain. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2071–2085.

- Lin, X.; Xiao, Y.; Song, Y.; Gan, C.; Deng, X.; Wang, P.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Peng, L.; Zhou, D.; et al. Rice microtubule-associated protein OsMAP65-3.1, but not OsMAP65-3.2, plays a critical role in phragmoplast microtubule organization in cytokinesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1030247.Lin, X.; Xiao, Y.; Song, Y.; Gan, C.; Deng, X.; Wang, P.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Peng, L.; Zhou, D.; et al. Rice microtubule-associated protein OsMAP65-3.1, but not OsMAP65-3.2, plays a critical role in phragmoplast microtubule organization in cytokinesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1030247.

- Beck, M.; Komis, G.; Müller, J.; Menzel, D.; Samaj, J. Arabidopsis homologs of nucleus- and phragmoplast-localized kinase 2 and 3 and mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 are essential for microtubule organization. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 755–771.Beck, M.; Komis, G.; Müller, J.; Menzel, D.; Samaj, J. Arabidopsis homologs of nucleus- and phragmoplast-localized kinase 2 and 3 and mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 are essential for microtubule organization. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 755–771.

- Beck, M.; Komis, G.; Ziemann, A.; Menzel, D.; Šamaj, J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 is involved in the regulation of mitotic and cytokinetic microtubule transitions in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 1069–1083.Beck, M.; Komis, G.; Ziemann, A.; Menzel, D.; Šamaj, J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 is involved in the regulation of mitotic and cytokinetic microtubule transitions in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 1069–1083.

- Boruc, J.; Weimer, A.K.; Stoppin-Mellet, V.; Mylle, E.; Kosetsu, K.; Cedeño, C.; Jaquinod, M.; Njo, M.; De Milde, L.; Tompa, P.; et al. Phosphorylation of MAP65-1 by Arabidopsis aurora kinases is required for efficient cell cycle progression. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 582–599.Boruc, J.; Weimer, A.K.; Stoppin-Mellet, V.; Mylle, E.; Kosetsu, K.; Cedeño, C.; Jaquinod, M.; Njo, M.; De Milde, L.; Tompa, P.; et al. Phosphorylation of MAP65-1 by Arabidopsis aurora kinases is required for efficient cell cycle progression. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 582–599.

- Zhang, H.; Deng, X.; Sun, B.; Lee Van, S.; Kang, Z.; Lin, H.; Lee, Y.J.; Liu, B. Role of the BUB3 protein in phragmoplast microtubule reorganization during cytokinesis. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 485–494.Zhang, H.; Deng, X.; Sun, B.; Lee Van, S.; Kang, Z.; Lin, H.; Lee, Y.J.; Liu, B. Role of the BUB3 protein in phragmoplast microtubule reorganization during cytokinesis. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 485–494.

- Lee, Y.R.; Li, Y.; Liu, B. Two Arabidopsis phragmoplast-associated kinesins play a critical role in cytokinesis during male gam-etogenesis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2595–2605.Lee, Y.R.; Li, Y.; Liu, B. Two Arabidopsis phragmoplast-associated kinesins play a critical role in cytokinesis during male gametogenesis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2595–2605.

- Herrmann, A.; Livanos, P.; Lipka, E.; Gadeyne, A.; Hauser, M.T.; Van Damme, D.; Müller, S. Dual localized kinesin-12 POK2 plays multiple roles during cell division and interacts with MAP65-3. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e46085.Herrmann, A.; Livanos, P.; Lipka, E.; Gadeyne, A.; Hauser, M.T.; Van Damme, D.; Müller, S. Dual localized kinesin-12 POK2 plays multiple roles during cell division and interacts with MAP65-3. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e46085.

- Liu, B.; Lee, Y.J. Spindle assembly and mitosis in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2022, 73, 227–254.Liu, B.; Lee, Y.J. Spindle assembly and mitosis in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2022, 73, 227–254.

More