The ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine, two major agricultural powers, has numerous severe socio-economic consequences that are presently being felt worldwide and that are undermining the functioning of the global food system. The war has also had a profound impact on the European food system. Indeed, the European agricultural industry is a net importer of several commodities, such as inputs and animal feed. This vulnerability, combined with the high costs of inputs such as fertilizers and energy, creates production difficulties for farmers and threatens to drive up food prices, affecting food affordability and access. Higher input prices increase production costs and, ultimately, inflation. This may affect food security and increase (food) poverty.

- food security

- food supply

- food

- conflict

- Russia

- Ukraine

- war

1. Introduction

2. Food Security Challenges in the Prolonged Russian–Ukrainian Conflict

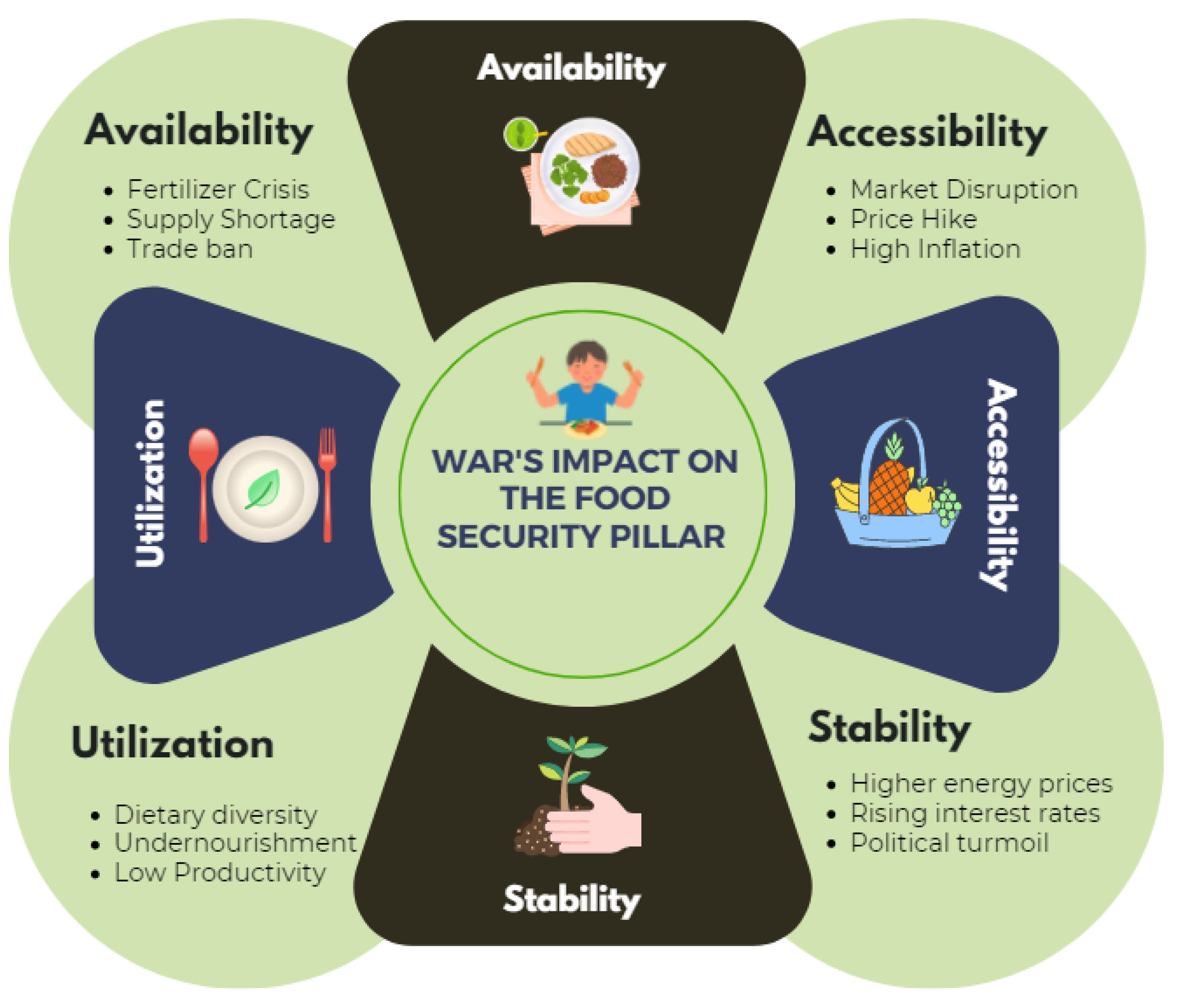

2.1. Threats Posed by War and Other Disruptions to Food Security

2.1.1. Availability

Ukraine has long been renowned as “Europe’s breadbasket” because of its abundance of “Chernozem”, or black soil, considered the most fertile farmland in the world, and has a high producing potential. Ukraine’s agricultural land area totals 41 million hectares, with 33 million hectares being arable, the equivalent of one-third of the EU’s total arable land area [62][54]. A significant fall in agricultural production and supply followed the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s and Russia and Ukraine became net importers of food [63][55]. However, Russian and Ukrainian agro-food output and exports have expanded considerably during the last three decades due to intense modernization and automation, making the region the world’s breadbasket [19]. In 2021, Russia and Ukraine exported nearly 12% of the food calories traded globally, making them essential actors in the global agri-food sector [23]. They are significant producers of staple agro-commodities such as wheat, corn, and sunflower oil and Russia is the largest exporter of fertilizers in the world. Further, Ukraine is one of the top three grain exporters, leading the world in soybean and sunflower oil exports. Ukraine controls 52.2% of the global sunflower oil market. Ukrainian agricultural exports have acquired a rising reputation in China, Egypt, India, Turkey, and the European Union [64][56].

As a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, global markets were disrupted. Short-term disruptions in global grain supply and long-term effects on natural gas and fertilizer markets negatively impacted producers during the planting season. This disruption might exacerbate already high food price inflation, posing a significant threat to low-income net food importers, many of whom have suffered a rise in malnutrition rates due to the pandemic disruptions [4].

Further, some issues will impact the 2023 harvest due to rising seed, transport, and fuel costs combined with low grain selling prices [68][57]. For instance, the transportation costs to ports have increased by over 100%, and the substitute option, which involves truck transport to Romania, costs nearly four times as much [69][58]. Accordingly, the sowing of winter wheat has decreased by 17% compared with the harvested area of 2022, while the estimated area for maize cultivation is reduced by 30% to 35% [67][59]. As a result, in 2023, Ukraine’s grain production and exports are anticipated to diminish by 20% and 15% compared with 2022.

In Europe, the food supply is not jeopardized since most European countries benefit from well-developed agricultural production. Except for tropical items (such as fruit, coffee, and tea), oilseeds (particularly soya), and natural fats and oils (including palm oil), the EU is self-sufficient in most food products [74][60]. The EU is generally self-sufficient in essential agricultural crops, including wheat and barley (which it is a net exporter of), maize, and sugar. The EU is also self-sufficient in a variety of animal products, including dairy and meat products, as well as fruits and vegetables [5]. Although Russia’s Ukraine conflict and climate change affect output, the EU’s food system remains robust and reliable. However, essential goods, such as animal feed, are net imported by the European agricultural industry. Due to this vulnerability and the high input costs, such as those for energy and fertilizers, farmers face productivity challenges and risk having food prices rise. This would reduce access to and availability of food [28]. Indeed, the substantial dependence of some European nations on the Russian energy supply makes it hard to avoid price increases on essential items such as food [29]. Ukraine was a key exporter of corn to Euro countries before the start of the conflict, accounting for 42% of EU grain imports in 2019, 30.5% in 2020, and 29.1% in 2021. Vegetable fat and oil imports from Ukraine were also significant, making up about 24% of EU imports between 2019 and 2021 before the crisis. Meanwhile, before the conflict, Russia accounted for approximately one-fifth of EU inorganic fertilizer imports. With the extensive usage of fertilizers in the EU, this may be destabilizing [29].

2.1.2. Accessibility

This pillar comprises variables that measure infrastructures for bringing food to market, individual indicators of people’s access to calories, and affordability of purchasing nutritional food. Accordingly, market disruption and rising inflation may put the food accessibility pillar in jeopardy [55][61]. Due to the Ukraine–Russia war, it will become even more difficult for some European low-income households to afford food.

The food supply in the EU is not jeopardized since most European countries benefit from well-developed agricultural production. Indeed, the EU is a significant producer of agri-food products—it was the world’s largest trader in 2021—and, although Russia’s conflict in Ukraine and climate change affect output, the EU’s food system remains robust and reliable. However, inflation and increased food prices affect EU citizens [76][62]. The steep rise in energy prices following the conflict impacts agriculture, an energy-intensive industry. Additionally, despite the recent price drops, the cost of fertilizers and other energy-intensive goods has remained high due to the war. Increased input costs translate into higher production expenses, thus raising food prices [23]. Accordingly, accessibility and affordability are the main consequences of the conflict on food security, especially for low-income and vulnerable populations that are disproportionately impacted [76][62].

Moreover, inflation caused by the conflict might cut private consumption by 1.1% in the European Union in 2022. However, the effect would vary by country. The impact will be felt more acutely in nations where consumption is more sensitive to energy and food costs and where a sizable proportion of the population is vulnerable to poverty. Central and south-eastern European countries are disproportionately impacted [82][63]. Europeans continuously feel the strain of the rise in food prices and the high inflation rate. As a result, many European citizens are losing buying power of necessary commodities. For instance, even Germany, which has solid domestic production and does not rely much on Ukrainian exports, is very susceptible to escalating inflation, driven mainly by the rising cost of Russian energy and fertilizer [29]. In November 2022, Germany’s consumer price index (CPI) year-over-year change was 10.0%. This was a modest decrease in the inflation rate from the +10.4% seen in October 2022. In November 2022, food prices increased by 21.1% compared with November 2021. This inflation rate is more than twice as high as the rate of general price inflation. The annual rate of inflation for food has been steadily climbing since January (October 2022: +20.3%). In November of 2022, prices increased across the board for all types of food. Edible fats and oils had the most significant price increase at 41.5%; dairy products and eggs increased by 34.0%; bread and cereals increased by 21.1%; vegetables increased by 21.1% [83][64].

2.1.3. Utilization

2.1.4. Stability

Since the outbreak of the Ukrainian conflict, Europe’s economic growth forecasts have been lowered downward, while inflation forecasts have risen. Most current predictions, which account for increased uncertainty and commodity price shocks, indicate that real GDP growth in the European Union might fall far below 3% in 2022, a drop of more than 1.3 percentage points from pre-war expectations. Additional supply chain disruptions and economic penalties are expected to send the European economy into a recession [82][63]. There has already been a substantial economic impact on European consumers due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, posing political risks to incumbent governments. Rising inflation, higher food prices, and food insecurity result in protests and strikes across Europe, underscoring growing discontent with skyrocketing living costs and threatening political turmoil.

As of January 2023, the slowdown in the global economy and fears of a worldwide recession have contributed to a general lowering of commodity prices. Nevertheless, commodity prices remain high relative to historical averages, extending the challenges connected with food security. Lower input costs, especially for fertilizers, are expected to contribute to a 5% drop in agricultural prices in 2023. Despite these forecasts, prices are projected to stay higher than pre-pandemic levels. As a result, global inflation will remain high in 2023 at 5.2% before decreasing to 3.2% in 2024. Although inflation is expected to decline gradually during 2023, underlying inflationary pressures may become more persistent [25]. According to the International Monetary Fund [94][65], global food prices are anticipated to stay high due to conflict, energy costs, and weather events, despite interest rate rises marginally easing pricing pressures.

2.2. Reshaping EU Food Security Amid the War Crisis

In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the European Parliament adopted a comprehensive resolution on 24 March 2022, endorsing many of the initiatives included in the European Commission’s package and calling for an urgent EU action plan to secure food security both inside and outside the EU [95][66]. EU leaders endorsed short-term and medium-term measures at the state levels to protect food security and strengthen the resilience of food systems. Most actions may be carried out using the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP). The EU members emphasized the importance of maintaining food supply security and took some immediate actions:

EU farmers support a package worth EUR 500 million to safeguard food security and strengthen the resilience of food systems. ● Reduction of energy import dependency and price shocks through REPowerEU plans. ● Maintaining the EU single market by avoiding restrictions and bans on exports. ● The Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived (FEAD) provides food and essential material support worth EUR 3.8 billion. ● Using the new CAP strategic plans to decrease reliance on gas, fuel, and inputs such as pesticides and fertilizers. ● A unique and temporary exception to enable the cultivation of any crops for food and feed on fallow land while farmers retain the full amount of the greening payment. ● Specific temporary exemptions from current animal feed import regulations [96,97,98,99][67][68][69][70]. Further strategies are needed to safeguard food security and bring resilience to the food system. The war has exposed the global food system’s fragility, emphasizing the significance of rebuilding the food system to strengthen resilience to future shocks, crises, and stressors [101][71]. As shown in Figure 52, several approaches are required, such as increasing food aid, ensuring fertilizer supply, imposing an energy price cap, initiating a farmer support package, switching to renewable energy sources for cultivation, changing individual food behaviors, lifting a trade ban, and political stability.

The food availability pillar has been jeopardized during Russia’s armed confrontation with Ukraine. As a result, the EU needs enough fertilizer at a reasonable price to make agricultural production more efficient to safeguard the food availability pillar. Maintaining equity in fertilizer access is a powerful lever for reducing food insecurity concerns in the short term. In the longer term, fair fertilizer usage must be supplemented with efforts to guarantee sustainable fertilizer use, ecosystem protection, and emission reductions [102][72]. However, export restrictions and bans must be avoided to preserve the EU single market. This will allow the EU and vulnerable countries to maintain a secure food supply. Food insecurity is the inability to consistently obtain adequate food to maintain an active and healthy lifestyle. On the contrary, food security can be established only through easy access to food, which the war has already impacted. The EU member states should impose a price cap on food to prevent adverse effects from market anomalies. Consequently, food would be more affordable and accessible to the EU people. In addition, the government needs to increase food aid to support the most vulnerable citizens in the EU. Furthermore, price caps can reduce inflation rates in the EU, which can promote food accessibility. Several measures can be taken to ensure food utilization, including minimizing food waste and loss, eating a healthy diet, or recycling food. Foods derived from plants are transformed into culinary creations that satisfy hunger, provide nutrients, and alleviate obesity. Indeed, adopting plant-based diets across Europe may boost food resilience in the face of the Russia–Ukraine war [27]. Households must always have access to adequate food to be food secure. In case of a sudden shock, such as a climatic or economic crisis or a war, they should not risk losing access to food. The armed conflict involving Russia in Ukraine impacts food stability in the EU and beyond. This situation requires a reduction in the interest rate to reduce food import prices and a reduction in Value-Added Tax (VAT), which is an alternative solution. Energy price caps protect consumers who default on basic energy tariffs from their suppliers. Putting a cap on energy prices ensures that businesses and individuals will pay a fair price, limiting food inflation, import costs, and retail prices. The significant trade-related impact of the war causes an increase in commodity prices. Indeed, energy, food products, and metals are three major commodities impacted by the war. Consequently, the significant price hike affects global markets and supply chains. Furthermore, commodity price hikes coupled with higher inflation rates on a global scale could result in changes in demand because people are unable or unwilling to make the usual food purchases. Furthermore, in the short term, measures aimed at preserving and expanding trade routes from Ukraine, enabling greater food production in vulnerable countries, and reducing harmful consumption in the EU are most adapted to addressing the present issues. While short-term solutions may mitigate the crisis’ negative effect, a long-term and systemic approach is required to strengthen its resilience [102][72]. As the European Commission [103][73] outlined, improving resilience through minimizing European agriculture’s reliance on energy, energy-intensive imports, and feed imports is more critical than ever. Resilience necessitates diverse import sources and market outlets through a solid global and bilateral trade strategy. Consequently, the Commission has asked member states to consider revising their Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) strategic plans to boost the sector’s resilience, increase renewable energy output, and decrease reliance on synthetic fertilizers via more sustainable production methods [103][73].

References

- Vos, R.; Glauber, J.; Hernández, M.; Laborde, D. COVID-19 and Rising Global Food Prices: What’s Really Happening? Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/covid-19-and-rising-global-food-prices-whats-really-happening (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Rice, B.; Hernández, M.A.; Glauber, J.; Vos, R. The Russia-Ukraine War Is Exacerbating International Food Price Volatility. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/russia-ukraine-war-exacerbating-international-food-price-volatility (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- NASA. Brazil Battered by Drought. Available online: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148468/brazil-battered-by-drought (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Glauber, J.; Laborde, D. How Will Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine Affect Global Food Security? Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/how-will-russias-invasion-ukraine-affect-global-food-security (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- European Parliament Question Time: Food Price Inflation in Europe. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2023/739298/EPRS_ATA(2023)739298_EN.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- FAO. Impact of the Ukraine-Russia Conflict on Global Food Security and Related Matters under the Mandate of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ni734en/ni734en.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Pereira, P.; Zhao, W.; Symochko, L.; Inacio, M.; Bogunovic, I.; Barcelo, D. The Russian-Ukrainian Armed Conflict Will Push Back the Sustainable Development Goals. Geogr. Sustain. 2022, 3, 277–287.

- Boston Consulting Group. The War in Ukraine and the Rush to Feed the World. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2022/how-the-war-in-ukraine-is-affecting-global-food-systems (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- KPMG. Ukraine-Russia Sector Considerations: Agriculture. Available online: https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2022/05/ukraine-russia-sector-considerations-agriculture.html (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Jagtap, S.; Trollman, H.; Trollman, F.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Parra-López, C.; Duong, L.; Martindale, W.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Hdaifeh, A.; et al. The Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Its Implications for the Global Food Supply Chains. Foods 2022, 11, 2098.

- Ben Hassen, T.; el Bilali, H. Impacts of the Russia-Ukraine War on Global Food Security: Towards More Sustainable and Resilient Food Systems? Foods 2022, 11, 2301.

- Bloem, J.R.; Farris, J. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Food Security in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Review. Agric. Food Secur. 2022, 11, 55.

- Galanakis, C.M. The “Vertigo” of the Food Sector within the Triangle of Climate Change, the Post-Pandemic World, and the Russian-Ukrainian War. Foods 2023, 12, 721.

- Foreign Affairs No One Would Win a Long War in Ukraine. Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/no-one-would-win-long-war-ukraine (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Allam, Z.; Bibri, S.E.; Sharpe, S.A. The Rising Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Russia–Ukraine War: Energy Transition, Climate Justice, Global Inequality, and Supply Chain Disruption. Resources 2022, 11, 99.

- Zhou, X.-Y.; Lu, G.; Xu, Z.; Yan, X.; Khu, S.-T.; Yang, J.; Zhao, J. Influence of Russia-Ukraine War on the Global Energy and Food Security. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188, 106657.

- European Commission. Safeguarding Food Security and Reinforcing the Resilience of Food Systems; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- FAO. The Importance of Ukraine and the Russian Federation for Global Agricultural Markets and the Risks Associated with the Current Conflict. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb9013en/cb9013en.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- OECD. Economic and Social Impacts and Policy Implications of the War in Ukraine. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/4181d61b-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/4181d61b-en (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Rabobank. The Russia-Ukraine War’s Impact on Global Fertilizer Markets. Available online: https://research.rabobank.com/far/en/sectors/farm-inputs/the-russia-ukraine-war-impact-on-global-fertilizer-markets.html (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Benton, T.; Froggatt, A.; Wellesley, L.; Grafham, O.; King, R.; Morisetti, N.; Nixey, J.; Schröder, P. The Ukraine War and Threats to Food and Energy Security: Cascading Risks from Rising Prices and Supply Disruptions. Available online: https://chathamhouse.soutron.net/Portal/Public/en-GB/RecordView/Index/191102 (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- FAO. The Importance of Ukraine and the Russian Federation for Global Agricultural Markets and the Risks Associated with the War in Ukraine. December 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cc3317en/cc3317en.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Hellegers, P. Food Security Vulnerability Due to Trade Dependencies on Russia and Ukraine. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1503–1510.

- World Bank Food Security Update. January 2023. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-update (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- World Bank Food Security Update. December 2022. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-update?cid=ECR_LI_worldbank_EN_EXT (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Sun, Z.; Scherer, L.; Zhang, Q.; Behrens, P. Adoption of Plant-Based Diets across Europe Can Improve Food Resilience against the Russia–Ukraine Conflict. Nat. Food. 2022, 3, 905–910.

- European Commission Commission. Acts for Global Food Security and for Supporting EU Farmers and Consumers. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_1963 (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- European Committee of the Regions Repercussions of the Agri-Food Crisis at Local and Regional Level. Available online: http://www.cor.europa.eu (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Tollefson, J. What the War in Ukraine Means for Energy, Climate and Food. Nature 2022, 604, 232–233.

- Menyhert, B. The Effect of Rising Energy and Consumer Prices on Household Finances, Poverty and Social Exclusion in the EU; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022.

- IMF. World Economic Outlook, October 2022: Countering the Cost-of-Living Crisis. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2022/10/11/world-economic-outlook-october-2022 (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- de Paulo Gewehr, L.L.; de Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O. Geopolitics of Hunger: Geopolitics, Human Security and Fragile States. Geoforum 2022, 137, 88–93.

- Lin, F.; Li, X.; Jia, N.; Feng, F.; Huang, H.; Huang, J.; Fan, S.; Ciais, P.; Song, X.-P. The Impact of Russia-Ukraine Conflict on Global Food Security. Glob. Food Sec. 2023, 36, 100661.

- Martin-Shields, C.P.; Stojetz, W. Food Security and Conflict: Empirical Challenges and Future Opportunities for Research and Policy Making on Food Security and Conflict. World Dev. 2019, 119, 150–164.

- FAO. Ukraine: Strategic Priorities for 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/fr/c/CC3385EN/ (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- USDA. Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus–Crop Production Maps. Available online: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/rssiws/al/up_cropprod.aspx (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- The New York Times. Mines, Fires, Rockets: The Ravages of War Bedevil Ukraine’s Farmers. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/04/world/europe/ukraine-russia-farms-farming-wheat-barley.html (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Bin-Nashwan, S.A.; Hassan, M.K.; Muneeza, A. Russia–Ukraine Conflict: 2030 Agenda for SDGs Hangs in the Balance. Int. J. Ethics. Syst. 2022. ahead of print.

- Nchasi, G.; Mwasha, C.; Shaban, M.M.; Rwegasira, R.; Mallilah, B.; Chesco, J.; Volkova, A.; Mahmoud, A. Ukraine’s Triple Emergency: Food Crisis amid Conflicts and COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e862.

- Lopes, H.; Martin-Moreno, J. ASPHER Statement: 5 + 5 + 5 Points for Improving Food Security in the Context of the Russia-Ukraine War. An Opportunity Arising from the Disaster? Public Health Rev. 2022, 43.

- von Cramon-Taubadel, S. Krieg Produziert Hunger. Osteuropa 2022, 72, 13.

- Hall, D. Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine and Critical Agrarian Studies. J. Peasant Stud. 2023, 50, 26–46.

- Hatab, A.A. Africa’s Food Security under the Shadow of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict. Strateg. Rev. South. Afr. 2022, 44.

- Gross, M. Global Food Security Hit by War. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R341–R343.

- Behnassi, M.; el Haiba, M. Implications of the Russia–Ukraine War for Global Food Security. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 754–755.

- von Cramon-Taubadel, S. Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine–Implications for Grain Markets and Food Security. Ger. J. Agric. Econ. 2022, 71, 1–13.

- Ma, Y.; Lyu, D.; Sun, K.; Li, S.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, R.; Zheng, M.; Song, K. Spatiotemporal Analysis and War Impact Assessment of Agricultural Land in Ukraine Using RS and GIS Technology. Land 2022, 11, 1810.

- Martinho, V.J.P.D. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Russia–Ukraine Conflict on Land Use across the World. Land 2022, 11, 1614.

- Nasir, M.A.; Nugroho, A.D.; Lakner, Z. Impact of the Russian–Ukrainian Conflict on Global Food Crops. Foods 2022, 11, 2979.

- Yazbeck, N.; Mansour, R.; Salame, H.; Chahine, N.B.; Hoteit, M. The Ukraine–Russia War Is Deepening Food Insecurity, Unhealthy Dietary Patterns and the Lack of Dietary Diversity in Lebanon: Prevalence, Correlates and Findings from a National Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3504.

- Bentley, A.R.; Donovan, J.; Sonder, K.; Baudron, F.; Lewis, J.M.; Voss, R.; Rutsaert, P.; Poole, N.; Kamoun, S.; Saunders, D.G.O.; et al. Near- to Long-Term Measures to Stabilize Global Wheat Supplies and Food Security. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 483–486.

- Carriquiry, M.; Dumortier, J.; Elobeid, A. Trade Scenarios Compensating for Halted Wheat and Maize Exports from Russia and Ukraine Increase Carbon Emissions without Easing Food Insecurity. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 847–850.

- Pereira, P.; Bašić, F.; Bogunovic, I.; Barcelo, D. Russian-Ukrainian War Impacts the Total Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 837, 155865.

- FAO FAOSTAT. Ukraine. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#country/230 (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Bokusheva, R.; Hockmann, H.; Kumbhakar, S.C. Dynamics of Productivity and Technical Efficiency in Russian Agriculture. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2012, 39, 611–637.

- Leshchenko, R. Ukraine Can Feed the World. Available online: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/ukraine-can-feed-the-world/ (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Reuters Ukraine Farmers May Cut Winter Grain Sowing by at Least 30%–Union. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/ukraine-crisis-grain-sowing-idAFL1N30J0CL (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- The New York Times. How Russia’s War on Ukraine Is Worsening Global Starvation. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/02/us/politics/russia-ukraine-food-crisis.html (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Knowledge Centre for Global Food and Nutrition Security. The Impact of Russia’s War against Ukraine on Global Food Security-Impact on Global Agricultural Production and Exports Impact on Ukrainian Production and Exports. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/Impact%20of%20Russia%20war%20against%20Ukraine%20on%20global%20food%20security_knowledge%20review%206_final.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Berkhout, P.; Bergevoet, R.; van Berkum, S. A Brief Analysis of the Impact of the War in Ukraine on Food Security. Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/596254 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- UN High Level Task Force on Global Food Security. Food and Nutrition Security: Comprehensive Framework for Action. Summary of the Updated Comprehensive Framework for Action (UCFA); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011.

- European Council Food Security and Affordability. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/food-security-and-affordability/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- European Investment Bank. How Bad Is the Ukraine War for the European Recovery? Available online: www.eib.org/economics (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- German Federal Statistical Office Inflation Rate at +10.0% in November 2022. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2022/12/PE22_529_611.html (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- IMF. Global Food Prices to Remain Elevated Amid War, Costly Energy, La Niña. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/12/09/global-food-prices-to-remain-elevated-amid-war-costly-energy-la-nina (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- European Parliament Need for an Urgent EU Action Plan to Ensure Food Security inside and Outside the EU in Light of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0099_EN.html (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- European Commission Increased Support for EU Farmers through Rural Development Funds. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_3170 (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- European Commission REPowerEU: Affordable, Secure and Sustainable Energy for Europe. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/repowereu-affordable-secure-and-sustainable-energy-europe_en (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- European Commission Diverse Approaches to Supporting Europe’s Most Deprived: FEAD Case Studies 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/european-social-fund-plus/en/publications/2021-fead-network-case-study-catalogue (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- European Commission CAP Strategic Plans and Commission Observations. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/cap-my-country/cap-strategic-plans_en (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Dyson, E.; Helbig, R.; Avermaete, T.; Halliwell, K.; Calder, P.C.; Brown, L.R.; Ingram, J.; Popping, B.; Verhagen, H.; Boobis, A.R.; et al. Impacts of the Ukraine–Russia Conflict on the Global Food Supply Chain and Building Future Resilience. EuroChoices 2023.

- Zachmann, G.; Weil, P.; von Cramon-Taubadel, S. A European Policy Mix to Address Food Insecurity Linked to Russia’s War. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/european-policy-mix-address-food-insecurity-linked-russias-war#toc-2-2-effects-on-prices (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- European Commission. New Common Agricultural Policy: Set for 1 January 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_7639 (accessed on 21 January 2023).